The Earth’s Vital Stitches: Understanding Protected Areas

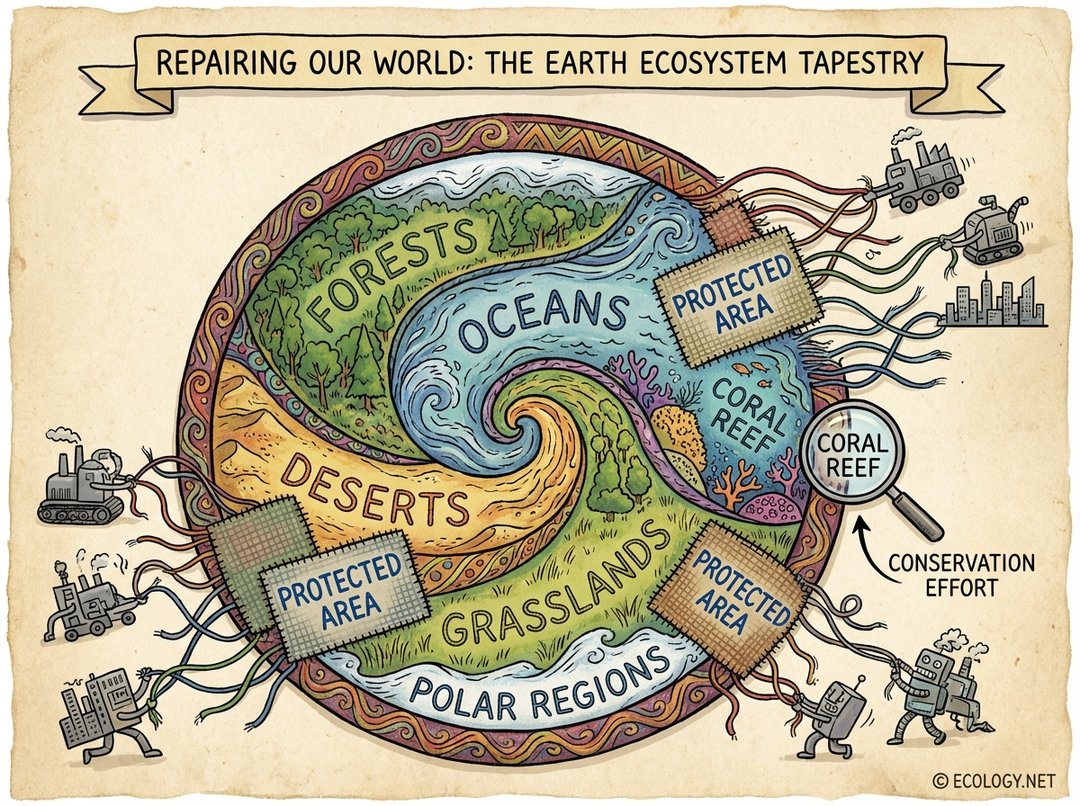

Imagine our planet’s incredible biodiversity, its intricate web of life, as a magnificent, ancient tapestry. This tapestry, woven over millennia, features vibrant forests, teeming oceans, majestic mountains, and bustling wetlands, each thread representing a species, an ecosystem, or a crucial natural process. For centuries, human activity has pulled at these threads, causing parts of this precious fabric to fray, unravel, and even disappear. But humanity has also recognized this damage and begun to mend. The “stitches” in this global repair effort are what we call protected areas.

Protected areas are designated geographical spaces, recognized, dedicated, and managed through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values. They are our planet’s designated safe havens, critical for safeguarding biodiversity, maintaining ecological processes, and providing essential services that underpin all life, including our own. From the smallest nature reserve to vast national parks, these areas serve as bulwarks against habitat loss, species extinction, and environmental degradation. They are not merely fences around pristine wilderness; they are dynamic tools for conservation, research, education, and even sustainable recreation.

Why Are Protected Areas So Crucial?

The importance of protected areas extends far beyond simply preserving pretty landscapes. They are fundamental to the health and stability of the entire planet.

- Biodiversity Hotspots: Many protected areas are established in regions with exceptionally high biodiversity, often housing rare, endangered, or endemic species found nowhere else on Earth.

- Ecosystem Services: These areas provide invaluable “services” for free. This includes clean air and water, pollination for crops, climate regulation, flood control, and soil fertility. For example, protected forests act as giant carbon sinks, absorbing greenhouse gases, while protected wetlands filter pollutants from water.

- Scientific Research and Education: They serve as living laboratories for scientists to study ecological processes, monitor species, and understand the impacts of environmental change. They also offer unparalleled opportunities for environmental education, fostering a deeper connection to nature for future generations.

- Cultural and Spiritual Value: Many protected areas hold deep cultural, spiritual, and historical significance for indigenous peoples and local communities, preserving traditional ways of life and sacred sites.

- Economic Benefits: Ecotourism, when managed sustainably, can provide significant economic benefits to local communities, creating jobs and incentivizing conservation.

A Spectrum of Protection: Diverse Types of Protected Areas

The term “protected area” encompasses a vast array of sites, each with unique characteristics, management goals, and levels of protection. This diversity allows for tailored conservation approaches to suit different ecological contexts and human needs.

Here are some common categories:

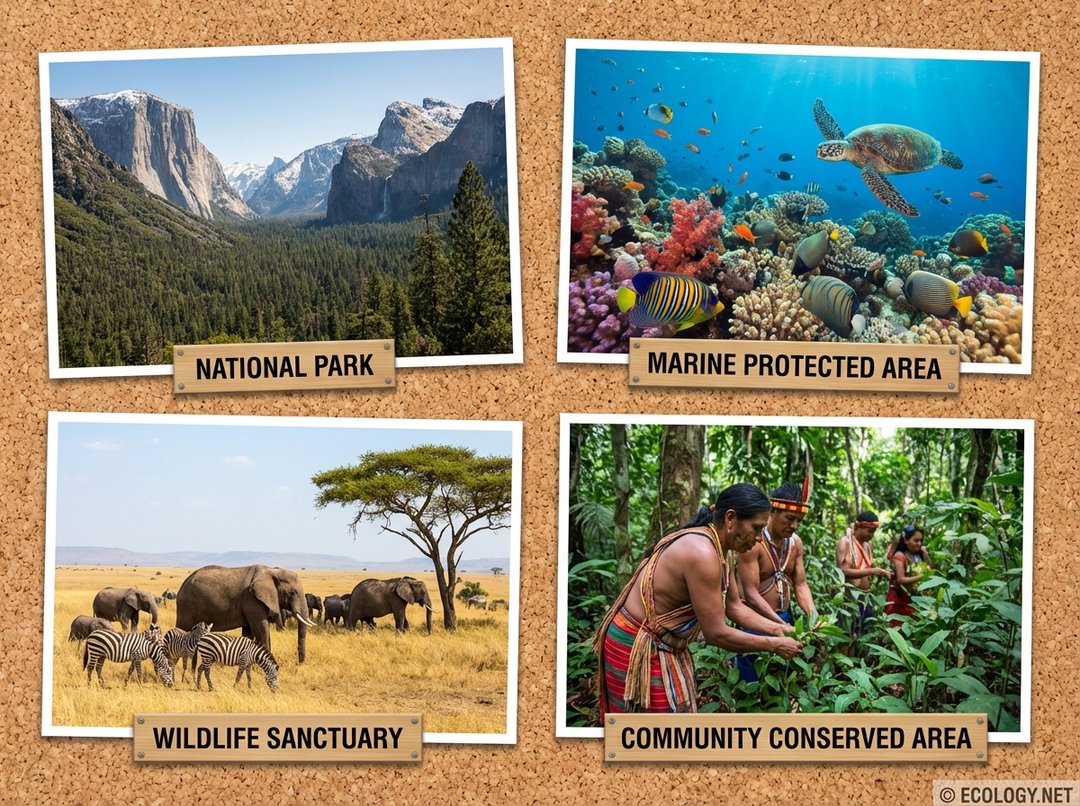

- National Parks: Typically large natural or near-natural areas set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, along with the complement of species and ecosystems characteristic of the area. They often provide a foundation for environmentally and culturally compatible spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational, and visitor opportunities. Think of vast wildernesses with iconic wildlife and stunning scenery.

- Wildlife Sanctuaries and Nature Reserves: These areas are often smaller and more focused on protecting specific species or habitats. A wildlife sanctuary might be dedicated to providing a safe haven for migratory birds, while a nature reserve could protect a rare type of forest or wetland.

- Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): Covering oceans, estuaries, and the Great Lakes, MPAs are crucial for conserving marine biodiversity, protecting fish stocks, and maintaining healthy ocean ecosystems like coral reefs, kelp forests, and deep-sea habitats. They can range from fully protected “no-take” zones to areas allowing sustainable fishing.

- Community Conserved Areas (CCAs): These are areas where indigenous peoples and local communities, through customary laws or other effective means, play a primary role in the management and conservation of natural resources. This approach recognizes the deep traditional knowledge and stewardship of local populations.

- Other Designations:

- UNESCO Biosphere Reserves: These are sites recognized for their unique biological and cultural significance, promoting solutions reconciling the conservation of biodiversity with its sustainable use. They often have core protected areas surrounded by buffer zones and transition areas where sustainable development is encouraged.

- Ramsar Sites: Wetlands of international importance, designated under the Ramsar Convention, are crucial for waterbird habitats and the provision of vital ecosystem services.

Beyond Boundaries: The Crucial Role of Connectivity

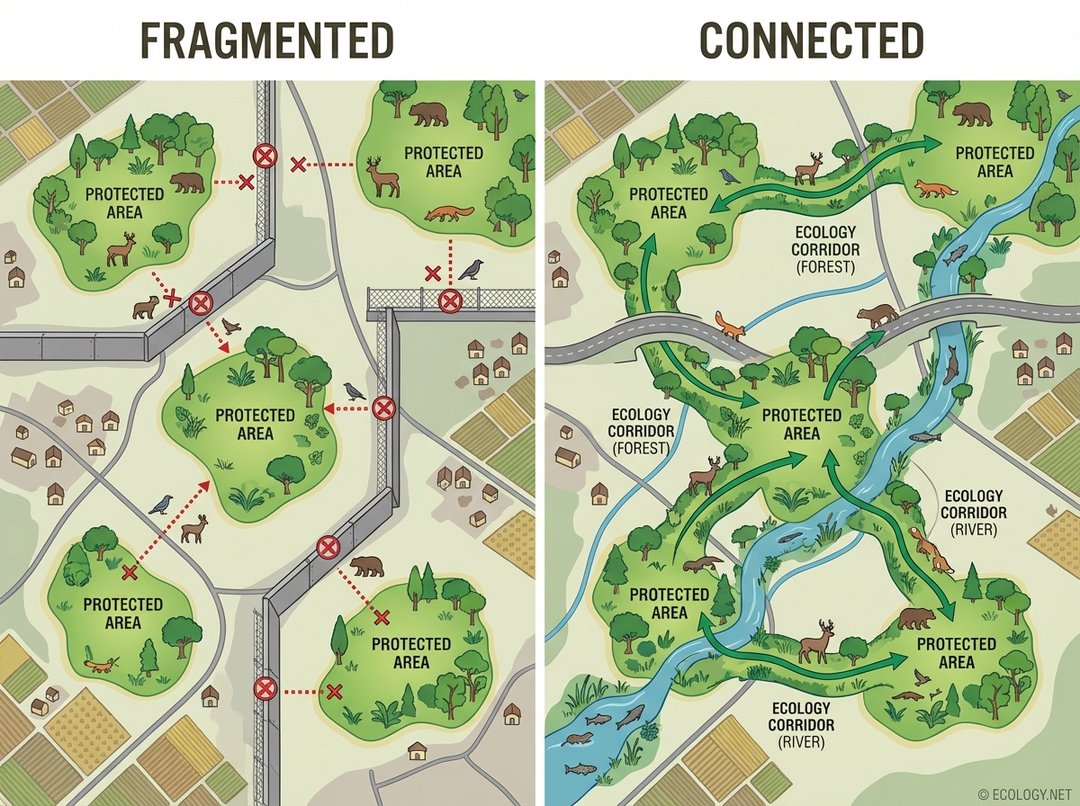

While establishing individual protected areas is vital, their effectiveness can be significantly enhanced when they are not isolated islands in a sea of human development. The concept of “connectivity” is paramount in modern conservation.

Habitat fragmentation, caused by roads, urban sprawl, and agricultural expansion, can turn protected areas into isolated pockets. This isolation prevents animals from moving between areas to find food, mates, or new habitats, especially in response to climate change. It can lead to inbreeding, reduced genetic diversity, and increased vulnerability to local extinctions.

This is where ecological corridors come into play. These are strips of natural habitat, such as river systems, forest belts, or even specially designed wildlife crossings, that link protected areas. Corridors allow for:

- Gene Flow: Enabling animals to move between populations, preventing inbreeding and maintaining genetic health.

- Species Dispersal: Allowing young animals to find new territories and populations to expand.

- Climate Change Adaptation: Providing pathways for species to shift their ranges in response to changing temperatures and precipitation patterns.

- Increased Resilience: Creating larger, more robust networks of habitat that are better able to withstand disturbances.

The Science Behind the Stitches: Deeper Dive into Management and Challenges

Effective protected area management is a complex, dynamic process that requires scientific understanding, adaptive strategies, and collaborative efforts.

Management Strategies

- Zoning: Many large protected areas employ zoning, dividing the area into different sections with varying levels of protection and permitted activities. For instance, a core zone might be strictly protected for wilderness and research, surrounded by buffer zones where sustainable tourism or traditional resource use is allowed.

- Adaptive Management: Conservation is not static. Managers continuously monitor ecological conditions, assess the effectiveness of their strategies, and adapt their approaches based on new information and changing circumstances. This iterative process ensures that management remains relevant and effective.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Successful protected areas often involve a wide range of stakeholders, including government agencies, local communities, indigenous groups, scientists, and non-governmental organizations. Collaborative governance fosters shared responsibility and ensures that diverse perspectives are considered.

Persistent Threats and Challenges

Despite their vital role, protected areas face numerous threats that challenge their long-term effectiveness:

- Poaching and Illegal Logging: The illicit trade in wildlife and timber continues to devastate populations and habitats within protected zones.

- Encroachment and Habitat Loss: Pressure from expanding agriculture, human settlements, and infrastructure development can lead to the shrinking or degradation of protected lands.

- Climate Change: Shifting weather patterns, increased frequency of extreme events like wildfires and floods, and rising sea levels pose significant threats to the ecosystems and species within protected areas.

- Insufficient Funding and Capacity: Many protected areas, particularly in developing nations, suffer from a lack of financial resources, trained personnel, and adequate equipment to enforce regulations and implement effective management plans.

- Human-Wildlife Conflict: As human populations expand, interactions between people and wildlife can increase, leading to conflicts over resources or safety concerns, which can undermine conservation efforts.

Measuring Effectiveness and Future Outlook

Assessing the effectiveness of protected areas is crucial. This involves monitoring biodiversity trends, habitat health, and the socio-economic impacts on local communities. Tools like remote sensing, ecological surveys, and community-based monitoring help track progress and identify areas needing improvement.

Globally, there is a growing recognition of the need to expand and strengthen protected area networks. International targets, such as the “30×30” goal to protect 30% of land and sea by 2030, reflect a collective ambition to scale up conservation efforts. Achieving these goals requires not only establishing new protected areas but also ensuring their equitable and effective management, fostering connectivity, and integrating them into broader landscape and seascape planning.

Conclusion: Our Shared Responsibility

Protected areas are more than just lines on a map; they are living laboratories, cultural treasures, and the very life support systems of our planet. They represent a profound commitment to safeguarding the natural world for current and future generations. Understanding their purpose, appreciating their diversity, and supporting their continued existence is a shared responsibility. By reinforcing these vital stitches in Earth’s tapestry, we ensure a healthier, more resilient planet for all.