In the intricate tapestry of life on Earth, every organism plays a crucial role. Yet, at the very foundation of nearly every ecosystem lies a group of organisms so vital that without them, life as we know it would simply cease to exist. These unsung heroes are known as producers.

From the towering trees of the Amazon rainforest to the microscopic algae drifting in the vast oceans, producers are the ultimate architects of life, converting raw energy into the sustenance that fuels all other living things. Understanding producers is not just a scientific curiosity; it is key to grasping the fundamental mechanics of our planet’s biology and the delicate balance that sustains us all.

What Are Producers and Why Are They Important?

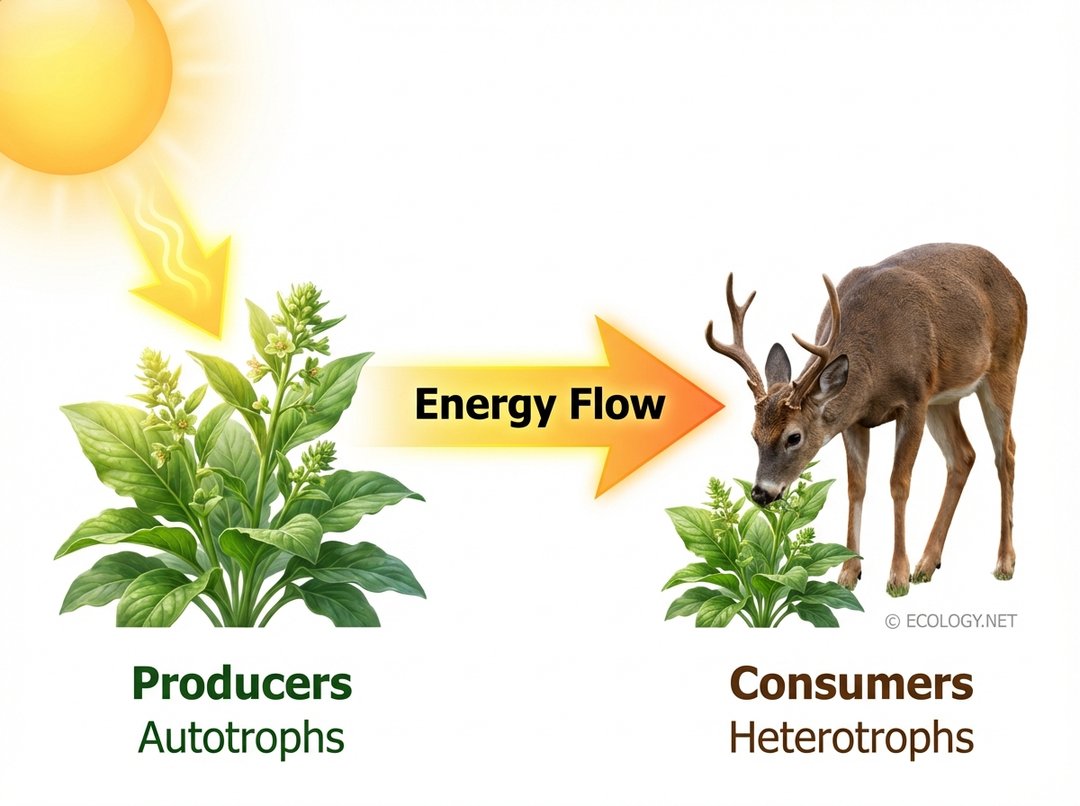

At its core, a producer is an organism that creates its own food, typically using energy from sunlight or chemical reactions. Scientists often refer to producers as autotrophs, a term derived from Greek meaning “self-feeders.” This ability to generate their own organic compounds from inorganic sources sets them apart from all other life forms.

Conversely, organisms that cannot produce their own food and must obtain energy by consuming other organisms are called consumers, or heterotrophs. This fundamental distinction highlights the producers’ irreplaceable role as the entry point of energy into almost every food web.

Consider a simple scenario: a plant captures sunlight and converts it into sugars. A deer then eats the plant, gaining energy. A wolf might then prey on the deer, acquiring energy from the deer. In this chain, the plant is the producer, the deer is a primary consumer, and the wolf is a secondary consumer. Without the plant, the entire chain collapses.

Producers are the bedrock of all ecosystems, whether terrestrial or aquatic. They are responsible for generating the organic matter and energy that supports every other trophic level. Without them, there would be no food for herbivores, and consequently, no food for carnivores that feed on herbivores, leading to a complete collapse of the ecosystem. They are, quite literally, the foundation of life.

The Two Main Types of Autotrophs

While most people associate producers with plants, there are two primary categories based on their energy source:

- Photoautotrophs: These organisms use light energy to synthesize organic compounds. This group includes most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. They are the most common type of producer on Earth.

- Chemoautotrophs: These organisms use energy from chemical reactions (often involving inorganic compounds like hydrogen sulfide or ammonia) to produce food. They are typically bacteria or archaea found in extreme environments, such as deep-sea hydrothermal vents or hot springs, where sunlight cannot penetrate.

The Power of Photosynthesis

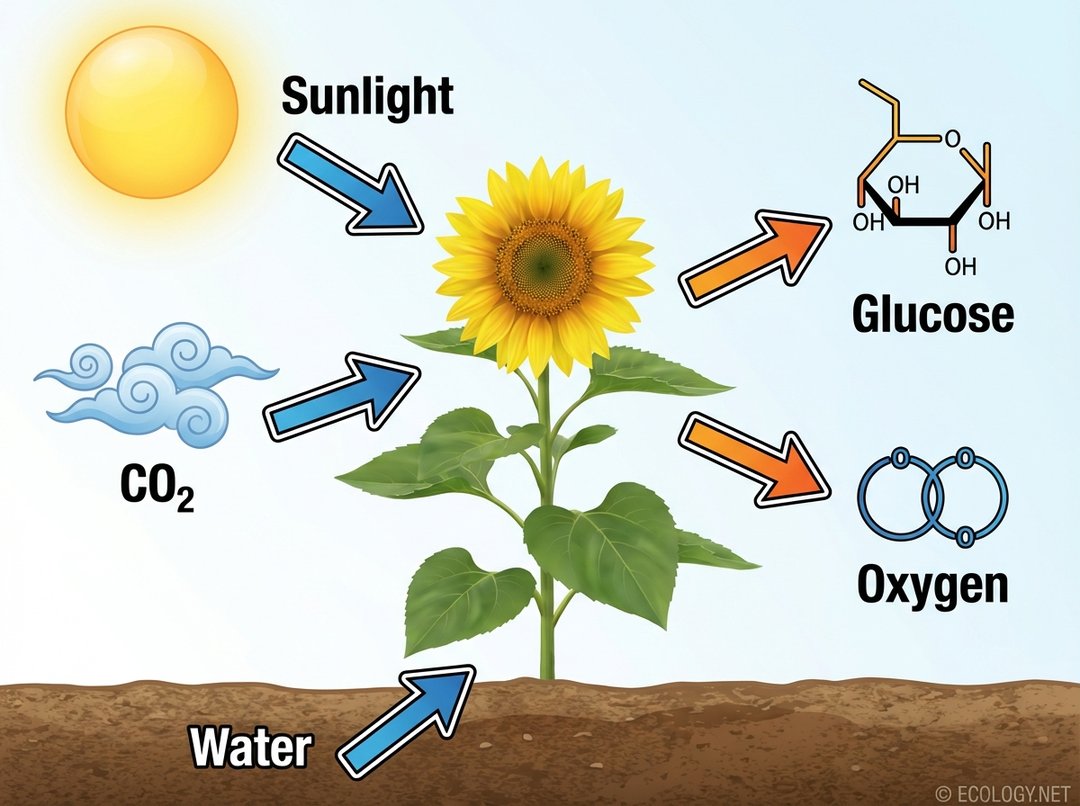

For the vast majority of producers, the magic happens through a process called photosynthesis. This incredible biochemical pathway allows organisms to harness the sun’s energy and transform it into chemical energy in the form of glucose (sugar).

The process can be summarized as follows:

Sunlight + Carbon Dioxide (CO2) + Water (H2O) → Glucose (C6H12O6) + Oxygen (O2)

Plants, algae, and cyanobacteria contain a green pigment called chlorophyll, which is essential for capturing light energy. This energy is then used to convert carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water absorbed from the soil into glucose, which serves as the plant’s food, and oxygen, which is released as a byproduct.

The oxygen released during photosynthesis is crucial for the survival of most aerobic organisms, including humans. It replenishes the atmospheric oxygen that we breathe, making photosynthesis not just a food-making process, but a life-sustaining one for the entire planet.

Beyond Sunlight: Chemosynthesis

While photosynthesis dominates the energy production landscape, it is important to acknowledge the fascinating world of chemosynthesis. In environments devoid of sunlight, such as the abyssal plains of the ocean or within rocks deep underground, certain bacteria and archaea have evolved to extract energy from chemical reactions.

For example, around hydrothermal vents, chemosynthetic bacteria oxidize hydrogen sulfide to produce energy, which they then use to convert carbon dioxide into organic matter. These chemosynthetic producers form the base of unique and vibrant ecosystems that thrive in complete darkness, demonstrating the incredible adaptability of life.

Trophic Levels and Energy Transfer

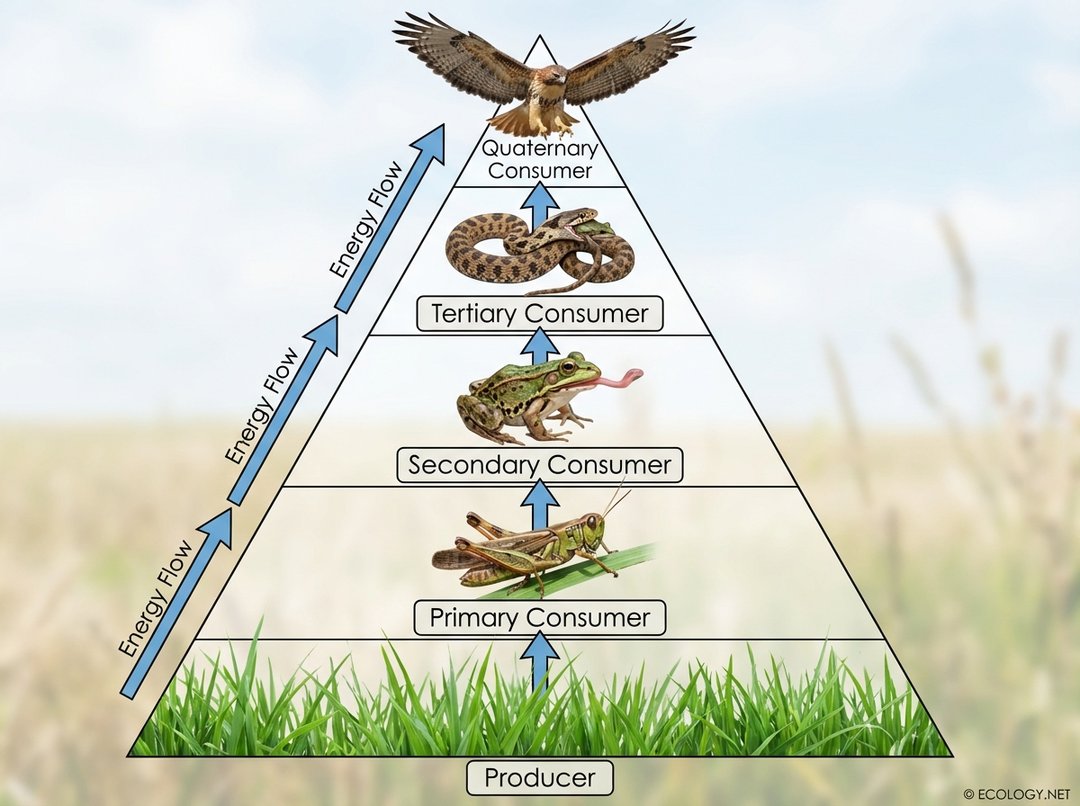

Producers occupy the lowest level of any food chain or food web, known as the first trophic level. A trophic level describes the position an organism occupies in a food chain. From this foundational level, energy flows upward through the ecosystem.

- First Trophic Level: Producers (e.g., plants, algae)

- Second Trophic Level: Primary Consumers (Herbivores, e.g., deer, rabbits, zooplankton) that eat producers.

- Third Trophic Level: Secondary Consumers (Carnivores or Omnivores, e.g., wolves, snakes, fish) that eat primary consumers.

- Fourth Trophic Level: Tertiary Consumers (Carnivores or Omnivores, e.g., eagles, sharks) that eat secondary consumers.

As energy moves from one trophic level to the next, a significant amount is lost, primarily as heat during metabolic processes. This phenomenon is often described by the “10% rule,” which suggests that only about 10% of the energy from one trophic level is transferred to the next. This dramatic energy loss explains why there are fewer organisms at higher trophic levels and why food chains rarely extend beyond four or five levels.

The total mass of living organisms at each trophic level is called biomass. Because of the energy loss, the biomass of producers is always far greater than the biomass of primary consumers, which in turn is greater than that of secondary consumers, and so on. This creates a pyramid structure, with producers forming the wide base.

Diverse Examples of Producers Across Ecosystems

Producers are incredibly diverse and can be found in virtually every corner of the Earth. Here are some key examples:

Terrestrial Ecosystems

- Trees: From mighty oaks and redwoods to delicate saplings, trees are dominant producers in forests, woodlands, and savannas. They provide vast amounts of biomass and oxygen.

- Grasses: Covering vast plains and prairies, grasses are crucial producers in grasslands, supporting large populations of grazing animals like bison, zebras, and cattle.

- Shrubs and Herbs: Smaller flowering plants, ferns, and mosses contribute significantly to the producer base in various terrestrial habitats, from tundras to deserts.

Aquatic Ecosystems

- Phytoplankton: These microscopic algae and cyanobacteria are the primary producers in oceans, lakes, and rivers. Despite their tiny size, their sheer numbers mean they produce a substantial portion of the Earth’s oxygen and form the base of nearly all aquatic food webs.

- Algae: Larger forms of algae, such as kelp and seaweed, create underwater forests that provide food and shelter for countless marine species.

- Aquatic Plants: Water lilies, cattails, and seagrasses are important producers in freshwater and coastal marine environments, offering food and habitat.

Extreme Environments

- Chemosynthetic Bacteria and Archaea: As mentioned, these microscopic organisms thrive in environments like hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, and deep subsurface habitats, forming the base of unique ecosystems where sunlight is absent.

The Indispensable Role of Producers in Ecosystems

The importance of producers extends far beyond simply providing food. Their activities underpin many critical planetary processes:

- Oxygen Production: Through photosynthesis, producers are the primary source of atmospheric oxygen, making the planet habitable for aerobic life.

- Carbon Cycle Regulation: Producers absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere for photosynthesis, playing a vital role in regulating Earth’s climate and mitigating the greenhouse effect. When they die, their carbon can be stored in soils or sediments, or released back into the atmosphere through decomposition.

- Nutrient Cycling: Producers absorb essential nutrients from the soil or water, incorporating them into organic compounds. When they are consumed or decompose, these nutrients are recycled back into the ecosystem, making them available for other organisms.

- Habitat Creation: Many producers, especially plants, create complex physical structures that serve as habitats, shelter, and breeding grounds for countless species. Forests, coral reefs (built by symbiotic algae), and seagrass beds are prime examples.

- Soil Formation and Stabilization: Plant roots help bind soil, preventing erosion and contributing to soil formation by adding organic matter.

- Biodiversity Support: By providing the energy and habitat, producers directly support the incredible diversity of life on Earth. A rich variety of producers often leads to a rich variety of consumers.

Threats to Producers and Their Ecosystems

Despite their fundamental importance, producers and the ecosystems they inhabit face numerous threats, largely due to human activities:

- Deforestation: The clearing of forests for agriculture, logging, and development directly destroys vast numbers of trees, reducing oxygen production and carbon sequestration.

- Pollution: Air and water pollution can harm producers. Acid rain damages plants, while nutrient runoff (eutrophication) in aquatic systems can lead to harmful algal blooms that deplete oxygen and create dead zones.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events can stress and kill producers, impacting their growth and distribution. Ocean acidification, a direct consequence of increased atmospheric CO2, threatens marine producers like phytoplankton and algae.

- Habitat Destruction: Urbanization, industrial expansion, and agricultural intensification lead to the loss and fragmentation of natural habitats, directly impacting producer populations.

- Invasive Species: Non-native species can outcompete native producers for resources, disrupting local ecosystems.

Protecting producers is not merely an environmental concern; it is a matter of safeguarding the very systems that sustain human life and all other life on Earth.

Conclusion

Producers are the silent powerhouses of our planet, tirelessly converting raw energy into the fuel that drives nearly every ecosystem. From the grand scale of forests and oceans to the microscopic world of bacteria, these autotrophs are the ultimate providers, generating the food, oxygen, and habitat that make life possible.

Understanding their critical role is the first step towards appreciating the delicate balance of nature and recognizing our responsibility to protect these foundational organisms. Every breath we take, every meal we eat, and every vibrant ecosystem we admire owes its existence to the tireless work of producers. Their health is, quite literally, the health of our planet.