Unraveling the Mystery of Where Life Lives: Understanding Population Distribution

Imagine looking out at a vast landscape. Do you see life spread evenly across it, or are there pockets of bustling activity interspersed with empty stretches? This fundamental observation lies at the heart of one of ecology’s most crucial concepts: population distribution. It is not just about how many individuals exist in an area, but precisely where they are located and why. Understanding these patterns is like deciphering a secret map that reveals the intricate dance between species and their environment, offering vital insights into their survival, interactions, and the health of entire ecosystems.

The Three Fundamental Patterns of Life’s Arrangement

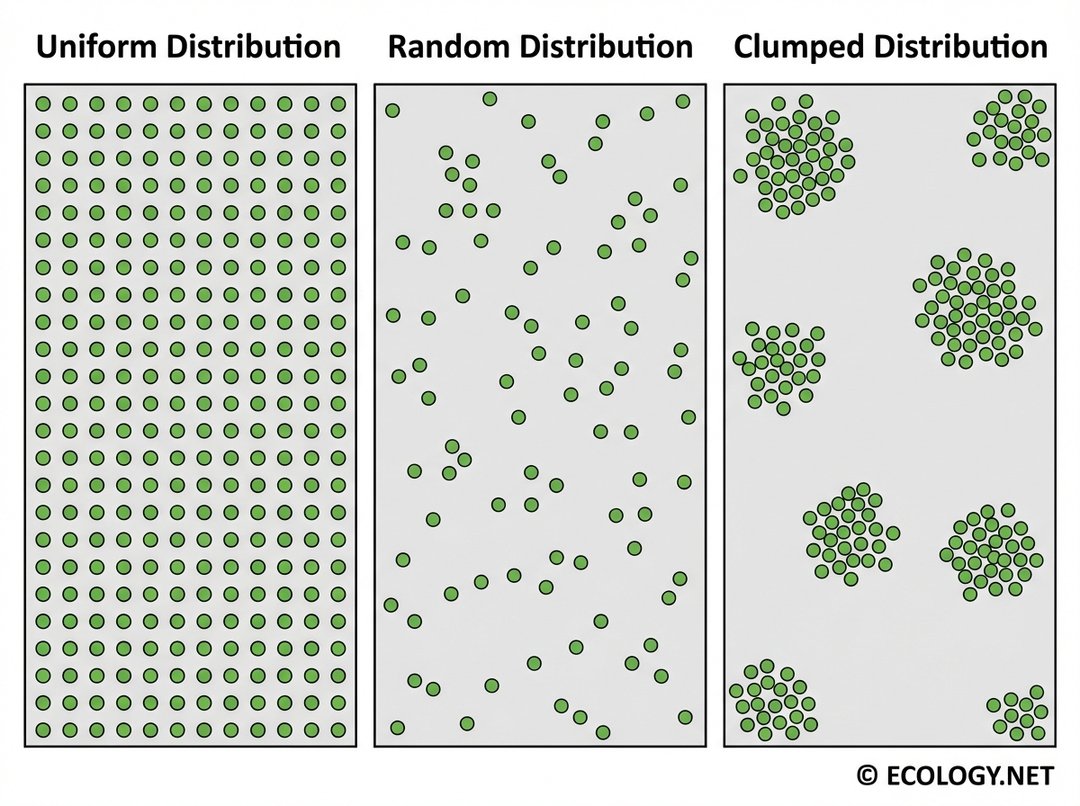

Ecologists categorize population distribution into three primary patterns, each telling a distinct story about the forces at play. These patterns are the foundational building blocks for understanding how species interact with their habitat and with each other.

1. Uniform Distribution: The Orderly Arrangement

In a uniform distribution, individuals are spaced out relatively evenly across the landscape. Think of rows of corn in a farmer’s field, or perhaps the territorial spacing of nesting seabirds on a cliff face. This pattern often arises when there is intense competition for resources, or when individuals actively defend their territory from others. Each individual or pair needs a certain amount of space or resources, leading to a predictable, almost grid-like arrangement.

- Examples:

- Creosote bushes in the desert, which release toxins to inhibit the growth of nearby plants, ensuring their own access to scarce water.

- Penguins nesting on a crowded rookery, maintaining a roughly equal distance from their neighbors to protect their nests.

- Certain agricultural crops planted in precise rows.

2. Random Distribution: The Unpredictable Scatter

A random distribution is characterized by individuals being scattered without any apparent pattern. The position of one individual does not influence the position of another. This is the least common pattern in nature because most organisms are influenced by resource availability, social interactions, or environmental factors. However, it can occur in environments where resources are abundant and evenly distributed, and there are no strong attractions or repulsions between individuals.

- Examples:

- Dandelion seeds dispersed by wind landing and germinating in a field with uniform soil conditions.

- Some species of trees in a mature tropical rainforest where competition for light and nutrients is less localized due to the sheer diversity and density.

3. Clumped Distribution: The Social Gathering

By far the most common pattern observed in nature, clumped distribution occurs when individuals are grouped together in patches. This clustering can be due to a variety of reasons, including the patchy distribution of resources, social behaviors, or reproductive strategies. When you see a herd of elephants, a school of fish, or a colony of ants, you are witnessing clumped distribution.

- Examples:

- Herds of wildebeest gathering around watering holes in the savanna.

- Flocks of birds migrating together for safety and efficiency.

- Fungal colonies growing on a decaying log, where resources are concentrated.

- Human populations concentrated in cities.

The Architects of Distribution: Factors Shaping Where Life Thrives

Why do these patterns emerge? The answer lies in a complex interplay of environmental conditions and biological interactions. Both non-living (abiotic) and living (biotic) factors act as powerful architects, sculpting the distribution of populations.

Abiotic Factors: The Environmental Blueprint

These are the non-living components of an ecosystem that dictate where organisms can survive and thrive.

- Temperature: Every species has an optimal temperature range. Too hot or too cold, and individuals cannot survive or reproduce effectively, leading to their absence in extreme climates. For instance, polar bears are restricted to Arctic regions, while cacti flourish in deserts.

- Water Availability: Water is essential for all life. Populations will naturally cluster around water sources in arid environments, or be absent entirely where water is scarce. Think of oases in deserts or riverbanks in drylands.

- Sunlight: Crucial for photosynthesis, sunlight dictates the distribution of plants, which in turn affects herbivores and their predators. Deep ocean environments, devoid of light, support vastly different life forms than sun-drenched surface waters.

- Soil pH and Nutrient Content: The chemical composition of soil directly influences plant growth. Certain plants prefer acidic soils, while others thrive in alkaline conditions, creating distinct vegetation patterns.

- Topography and Altitude: Mountains, valleys, and elevation changes create microclimates and barriers, influencing where species can live. Species adapted to high altitudes will not be found at sea level, and vice versa.

Biotic Factors: The Living Interactions

These are the interactions between living organisms that profoundly impact population distribution.

- Predation: The presence of predators can force prey populations to adopt certain distribution patterns, such as clumping for safety in numbers or spreading out to avoid detection. For example, gazelles might clump together to reduce individual risk when lions are present.

- Competition: When two or more species, or even individuals within the same species, vie for the same limited resources, it can lead to uniform distribution (as seen with creosote bushes) or exclude species from certain areas altogether.

- Disease: Pathogens can spread more easily in dense, clumped populations, potentially leading to localized extinctions and altering distribution patterns.

- Social Behavior: Many species exhibit social behaviors like schooling, herding, or colonial living, which inherently lead to clumped distributions. These behaviors offer benefits such as increased foraging efficiency, predator defense, or reproductive success.

- Reproduction and Dispersal: The way offspring are produced and spread can also influence distribution. Seeds dispersed by wind might lead to more random patterns, while those dropped directly by a parent plant might create clumps.

Beyond the Snapshot: Dynamics and Scale in Distribution

Population distribution is not static. It is a dynamic process, constantly shifting in response to environmental changes, seasonal variations, and the life cycles of organisms. A population might be clumped during breeding season but more dispersed during foraging. Furthermore, the observed pattern often depends on the scale at which it is viewed. A forest might appear to have a uniform distribution of trees when viewed from an airplane, but a closer look might reveal clumps of specific species. Understanding this multi-scale perspective is vital for accurate ecological assessment.

Advanced Insights: Habitat Fragmentation and Metapopulations

In an increasingly human-altered world, habitats are often broken up into smaller, isolated patches. This phenomenon, known as habitat fragmentation, poses significant challenges for many species. However, even in fragmented landscapes, life finds a way to persist through a fascinating concept called a metapopulation.

What is a Metapopulation?

A metapopulation is a “population of populations.” It consists of several spatially separated local populations of the same species that are interconnected by occasional dispersal of individuals. Imagine a series of small islands, each with its own population of a particular frog species. While each island population might be small and vulnerable to extinction, individuals occasionally migrate between islands. This movement, or dispersal, prevents the complete extinction of the species by allowing recolonization of empty patches or boosting the genetic diversity of struggling populations.

- Key Components of a Metapopulation:

- Habitat Patches: Discrete areas of suitable habitat where local populations can live.

- Unsuitable Matrix: The surrounding landscape that is inhospitable to the species, acting as a barrier between patches.

- Dispersal: The movement of individuals between patches, which is crucial for maintaining the overall metapopulation.

Ecological Significance and Conservation

The concept of metapopulations is incredibly important for conservation biology. In a world where natural habitats are shrinking and becoming increasingly fragmented, understanding how species persist in these patchy landscapes is critical. Conservation efforts often focus on maintaining connectivity between habitat fragments, creating “wildlife corridors” to facilitate dispersal and ensure the long-term viability of metapopulations. Without this dispersal, isolated populations become more susceptible to genetic drift, inbreeding, and local extinctions, ultimately leading to the loss of the entire species.

The intricate dance of dispersal and recolonization within a metapopulation highlights nature’s resilience, even in the face of habitat fragmentation. It underscores the importance of not just protecting individual patches, but also the connections between them.

Conclusion: The Enduring Importance of Distribution

From the precise spacing of desert shrubs to the vast migrations of wildebeest, population distribution is a fundamental ecological principle that underpins our understanding of life on Earth. It is a dynamic reflection of how species interact with their environment, compete for resources, avoid predators, and cooperate with their own kind. By studying these patterns, ecologists gain invaluable insights into the health of ecosystems, the impacts of environmental change, and the most effective strategies for conservation. Every clump, every uniform row, and every seemingly random scatter tells a story, and learning to read these stories is essential for safeguarding the biodiversity of our planet.