Unraveling the Mystery of Populations: A Cornerstone of Ecology

Imagine gazing out at a vast forest, a bustling city, or even a microscopic world teeming with bacteria. What do all these scenes have in common? They are all composed of populations. In the intricate dance of life on Earth, understanding populations is not just a scientific curiosity, it is a fundamental key to unlocking the secrets of ecosystems, predicting future trends, and safeguarding our planet’s biodiversity. From the smallest microbe to the largest whale, every living thing exists as part of a population, and their collective stories shape the world around us.

What Exactly is a Population?

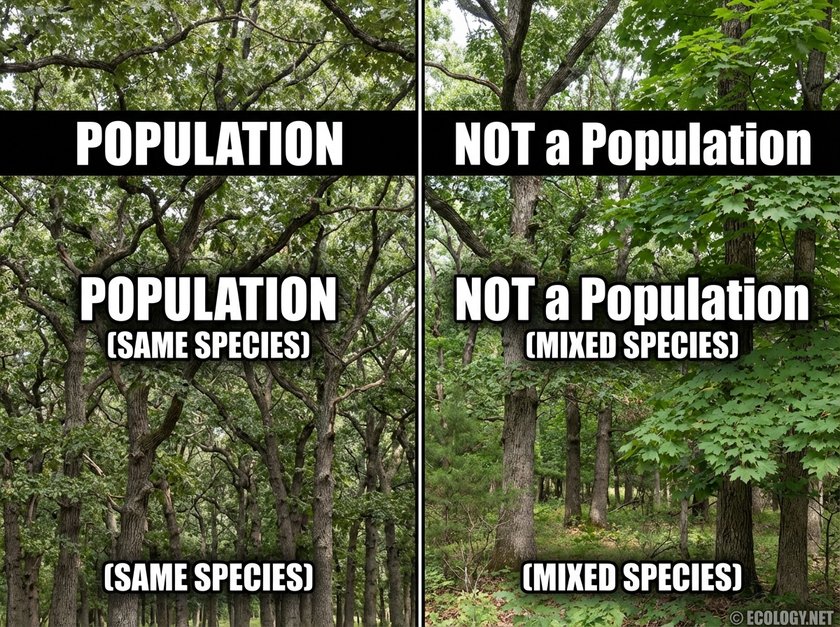

At its core, a population in ecology refers to a group of individuals of the same species living in the same geographical area at the same time. This seemingly simple definition carries profound implications. It is the “same species” part that is crucial. A herd of deer in a meadow is a population. A colony of ants in a mound is a population. All the oak trees in a particular forest stand form a population. However, a forest containing oak trees, maple trees, and pine trees is not a single population, but rather a community composed of multiple different populations.

This distinction is vital because individuals of the same species share common genetic traits, reproductive strategies, and ecological needs. They interact with each other in specific ways, competing for resources, mating, and influencing each other’s survival.

Why Do Ecologists Study Populations?

The study of populations, known as population ecology, is far more than an academic exercise. It provides critical insights for:

- Conservation: Understanding population sizes, trends, and threats helps us protect endangered species and manage wildlife.

- Resource Management: From fisheries to forestry, knowing how populations grow and decline allows for sustainable harvesting and resource allocation.

- Disease Control: Tracking the population dynamics of pathogens and their hosts is essential for public health.

- Pest Management: Predicting insect outbreaks or invasive species spread relies heavily on population ecology.

- Understanding Ecosystems: Populations are the building blocks of communities and ecosystems, and their interactions drive ecological processes.

Key Characteristics of Populations

Beyond simply existing, populations possess several measurable characteristics that ecologists use to understand their health, stability, and future trajectory.

Population Size and Density

The most straightforward characteristics are population size, which is the total number of individuals in a population, and population density, which is the number of individuals per unit area or volume. A large population size does not always mean high density. For example, a population of whales might be large in number but spread across a vast ocean, resulting in low density. Conversely, a bacterial colony might have a small total area but an incredibly high density. Both size and density influence how individuals interact and how they impact their environment.

Population Distribution

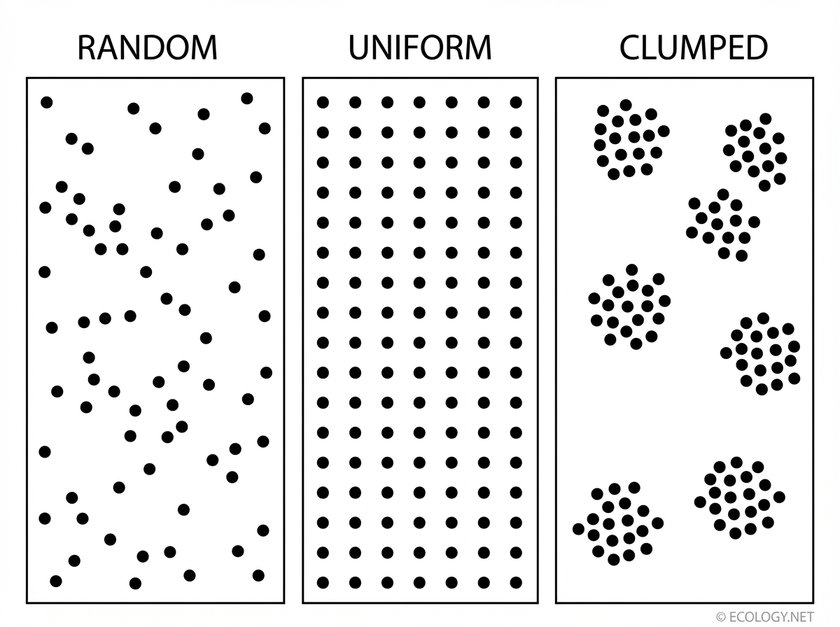

How individuals are spaced within their habitat is another critical characteristic. This spatial arrangement, or distribution pattern, can reveal much about a species’ behavior, resource needs, and interactions. Ecologists typically recognize three main types of distribution:

- Random Distribution: Individuals are scattered unpredictably, without any obvious pattern. This often occurs when resources are uniformly available and individuals do not strongly interact with each other, such as dandelions whose seeds are dispersed by wind.

- Uniform Distribution: Individuals are evenly spaced throughout the habitat. This pattern usually arises from competition for resources or territoriality, where individuals maintain a certain distance from one another. Examples include creosote bushes in deserts, which release toxins to inhibit nearby plant growth, or nesting penguins defending their territories.

- Clumped Distribution: Individuals are grouped in clusters. This is the most common distribution pattern in nature, often due to patchy resource availability, social behavior (like schooling fish or wolf packs), or limited dispersal capabilities. A grove of trees, a herd of elephants, or a colony of ants all exhibit clumped distribution.

Population Structure

Beyond mere numbers, the internal makeup of a population matters. This includes:

- Age Structure: The proportion of individuals in different age groups (pre reproductive, reproductive, and post reproductive). A population with a large proportion of young individuals is likely to grow, while one with many older individuals might be stable or declining.

- Sex Ratio: The proportion of males to females. This is particularly important for sexually reproducing species, as it directly impacts the reproductive potential of the population.

Population Dynamics: Births, Deaths, and Migration

Populations are not static entities. Their size and structure are constantly changing due to four fundamental processes:

- Births (Natality): The number of new individuals added to the population through reproduction.

- Deaths (Mortality): The number of individuals removed from the population through death.

- Immigration: The influx of individuals from other populations.

- Emigration: The outflow of individuals to other populations.

The balance of these factors determines whether a population grows, shrinks, or remains stable over time.

How Populations Grow and Change

The way populations increase in number is one of the most fascinating aspects of population ecology, revealing the interplay between a species’ inherent reproductive potential and the environmental constraints it faces.

Exponential Growth: The Ideal Scenario

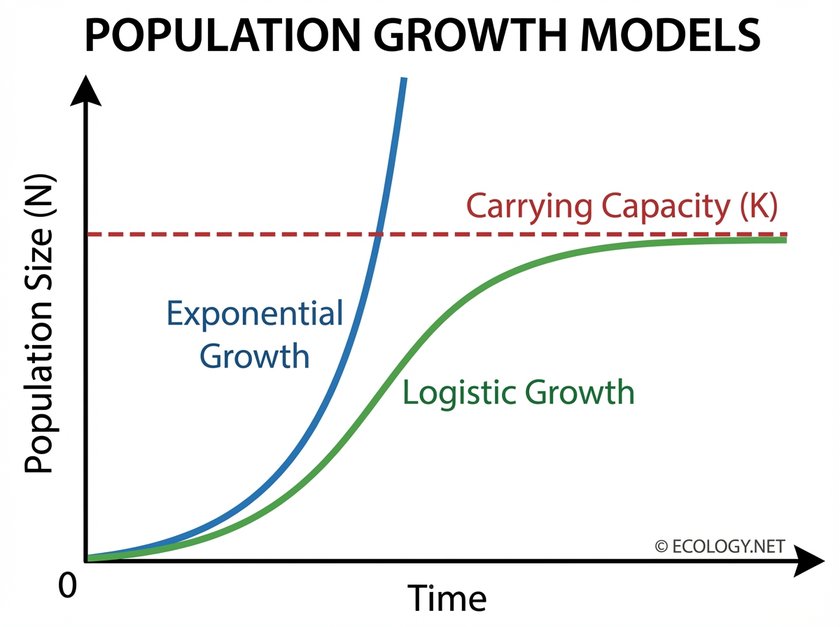

Under ideal conditions, with unlimited resources, no predators, and no disease, a population can grow at an ever accelerating rate. This is known as exponential growth, often depicted as a J shaped curve on a graph. Imagine a single bacterium that divides every 20 minutes. In just a few hours, it could produce millions of offspring. While rarely sustained in nature for long, exponential growth demonstrates a species’ biotic potential, its maximum reproductive capacity. It is often seen in new populations colonizing a pristine habitat or during recovery from a catastrophic event.

Logistic Growth: Reality Sets In

In the real world, resources are finite, and environments are not always ideal. As a population grows, it eventually encounters limiting factors that slow its growth. This leads to logistic growth, characterized by an S shaped curve.

The S curve begins with a period of exponential growth, but as the population approaches the environment’s capacity to support it, the growth rate slows down and eventually stabilizes. This stable population size is known as the carrying capacity (K). Carrying capacity represents the maximum population size that a particular environment can sustain indefinitely, given the available resources, space, and other limiting factors. When a population reaches its carrying capacity, birth rates generally equal death rates, and immigration balances emigration.

Factors Influencing Population Size

What are these “limiting factors” that dictate carrying capacity and regulate population growth? They can be broadly categorized into two types:

Density Dependent Factors

These factors have a greater impact as population density increases. They often involve interactions among individuals within the population or between the population and its immediate environment.

- Competition: As more individuals vie for the same limited resources (food, water, space, mates), competition intensifies, leading to reduced birth rates and increased death rates.

- Predation: Predator populations often increase as prey populations become denser, leading to more prey being caught and higher mortality rates for the prey.

- Disease: Diseases spread more easily and rapidly in dense populations, leading to higher mortality.

- Waste Accumulation: In some populations, particularly microorganisms, the buildup of metabolic waste products can become toxic at high densities.

Density Independent Factors

These factors affect population size regardless of the population’s density. They are often abiotic (non living) components of the environment.

- Natural Disasters: Events like floods, wildfires, earthquakes, and severe storms can decimate populations irrespective of how many individuals were present.

- Climate Change: Long term shifts in temperature, rainfall patterns, or ocean acidity can impact populations across vast areas, regardless of their density.

- Pollution: Environmental contaminants can harm populations regardless of their size or density.

Human Impact on Populations

Humans, as a dominant species on Earth, exert immense influence on the populations of countless other species. Our activities can lead to:

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Destroying or breaking up natural habitats directly reduces the carrying capacity for many species, leading to population declines.

- Overexploitation: Unsustainable hunting, fishing, or harvesting can deplete populations faster than they can reproduce, sometimes leading to extinction.

- Introduction of Invasive Species: Non native species can outcompete native populations for resources, introduce diseases, or prey on them, causing severe declines.

- Pollution: Chemical pollutants, plastic waste, and light or noise pollution can negatively impact the health and reproductive success of many populations.

Conversely, human efforts in conservation, habitat restoration, and sustainable management can help struggling populations recover and thrive. Understanding the principles of population ecology is therefore not just an academic pursuit, but a vital tool for responsible stewardship of our planet.

Conclusion

Populations are the living threads that weave the tapestry of life. From the simplest bacterial colony to the most complex human society, their dynamics, growth, and interactions shape ecosystems and determine the fate of species. By delving into the characteristics of population size, density, distribution, and the forces that drive their growth and decline, ecologists gain invaluable insights into the natural world. This knowledge empowers us to make informed decisions for conservation, resource management, and ultimately, for fostering a healthier, more sustainable planet for all populations, including our own.