Life on Earth is a testament to adaptation, and nowhere is this more evident than in the plant kingdom. From the scorching deserts to the icy tundras, and from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains, plants have developed an astonishing array of strategies to thrive in the face of relentless environmental challenges. These remarkable adjustments, known as plant adaptations, are the very essence of their survival, allowing them to capture sunlight, conserve water, deter predators, and reproduce successfully.

Understanding Plant Adaptations

At its core, a plant adaptation is any characteristic that helps a plant survive and reproduce in its specific environment. These adaptations are not conscious choices but rather traits that have evolved over millions of years through natural selection. Plants with traits better suited to their surroundings are more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass those advantageous traits to their offspring, leading to the gradual prevalence of these adaptations within a species.

Consider a plant living in a dry environment. If it develops a way to store water or reduce water loss, it has a better chance of survival than one without such a trait. Over generations, these water-saving features become common, defining the species’ ability to flourish in arid conditions. This continuous interplay between plants and their environment drives the incredible biodiversity we observe today.

The Three Pillars of Plant Adaptation

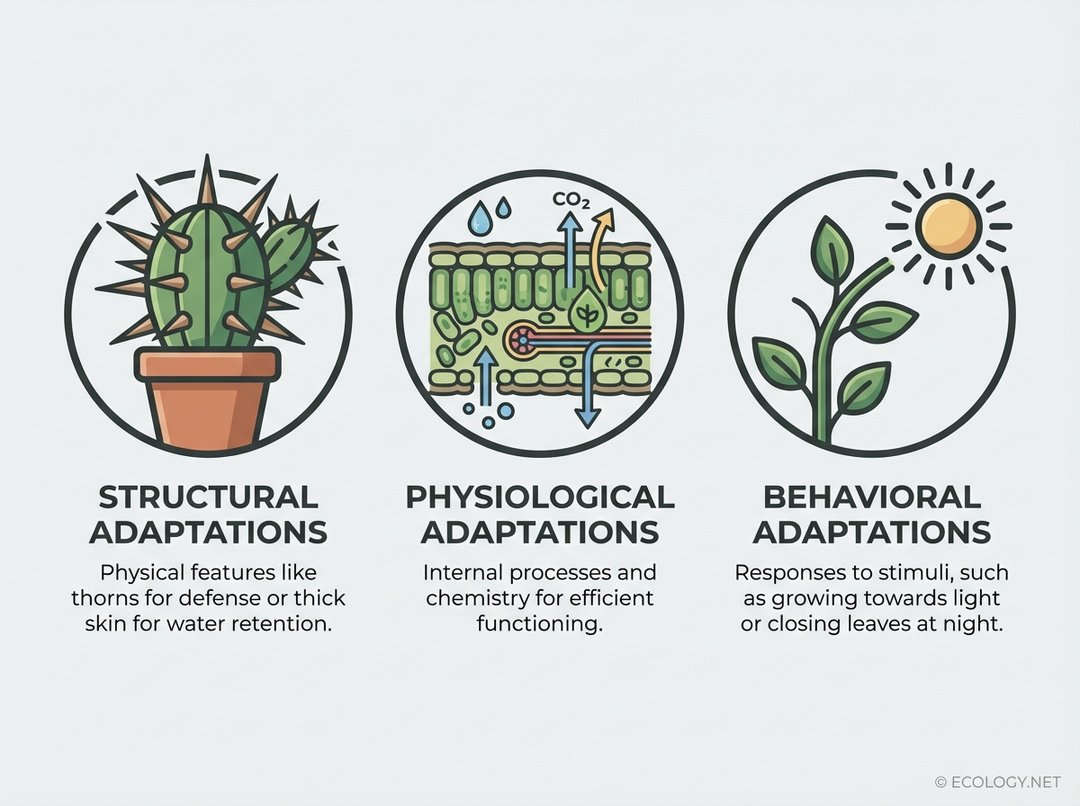

Plant adaptations can broadly be categorized into three main types: structural, physiological, and behavioral. Each category represents a different approach to overcoming environmental hurdles, often working in concert to ensure a plant’s success.

Structural Adaptations: The Physical Toolkit

Structural adaptations involve changes to a plant’s physical form or anatomy. These are often the most visible adaptations, shaping how a plant looks and feels. They are crucial for protection, support, and resource acquisition.

- Thorns and Spines: Many desert plants, like cacti, possess sharp thorns or spines. These are modified leaves or stems that serve as a formidable defense against herbivores seeking a juicy meal in a water-scarce landscape. They also help reduce airflow close to the plant surface, minimizing water loss.

- Waxy Cuticles: Leaves of many plants, especially those in dry or sunny environments, are covered with a thick, waxy layer called a cuticle. This waterproof coating significantly reduces water evaporation from the leaf surface, a vital adaptation for water conservation.

- Deep Root Systems: Plants in arid regions, such as mesquite trees, often develop extensive root systems that can penetrate deep into the soil to access groundwater far below the surface. Conversely, some desert plants have shallow, widespread roots to quickly absorb any surface rainfall.

- Succulence: Succulent plants, like aloes and sedums, have fleshy stems or leaves designed to store large quantities of water. This allows them to endure long periods without rain, slowly drawing upon their internal reserves.

- Broad Leaves: In contrast, plants in rainforests often have very large, broad leaves to maximize light capture in the dimly lit understory. Some even have “drip tips” to shed excess rainwater, preventing fungal growth.

Physiological Adaptations: The Internal Machinery

Physiological adaptations are internal, biochemical processes that allow plants to function efficiently under specific environmental conditions. These adaptations are often less visible but are equally critical for survival.

- CAM Photosynthesis: Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) is a remarkable adaptation found in many desert succulents and epiphytes. Unlike most plants that open their stomata (pores) during the day to take in carbon dioxide, CAM plants open their stomata only at night. This minimizes water loss through transpiration during the hot, dry daytime hours.

This diagram clarifies the complex physiological process of CAM photosynthesis, illustrating how plants adapt to conserve water by altering their stomatal activity based on the time of day.

- Antifreeze Proteins: Some plants in cold climates produce special proteins that act like antifreeze, preventing ice crystals from forming within their cells and damaging tissues during freezing temperatures.

- Salt Tolerance (Halophytes): Plants growing in saline environments, known as halophytes, have developed various mechanisms to cope with high salt concentrations. Some excrete salt through specialized glands on their leaves, while others accumulate salt in specific vacuoles or dilute it within their tissues.

- Nutrient Uptake Efficiency: In nutrient-poor soils, plants may form symbiotic relationships with fungi (mycorrhizae) that help them absorb nutrients more effectively. Carnivorous plants, like the Venus flytrap, have evolved to capture insects to supplement their nitrogen intake in boggy, nutrient-deficient habitats.

Behavioral Adaptations: Dynamic Responses

Behavioral adaptations refer to a plant’s dynamic responses to environmental stimuli. While plants do not “behave” in the same way animals do, they exhibit movements and growth patterns that are direct responses to their surroundings.

- Phototropism: This is the growth of a plant towards a light source. Stems and leaves exhibit positive phototropism, ensuring they receive maximum sunlight for photosynthesis.

- Gravitropism: Also known as geotropism, this is a plant’s growth response to gravity. Roots typically show positive gravitropism, growing downwards into the soil for anchorage and water, while shoots exhibit negative gravitropism, growing upwards towards light.

- Thigmotropism: The growth response to touch. Climbing plants, such as peas or morning glories, use tendrils that coil around supports when they come into contact, allowing the plant to climb upwards and access more light.

- Nyctinasty (Sleep Movements): Some plants, like the prayer plant or certain legumes, exhibit daily rhythmic movements where their leaves fold up at night and open during the day. This is thought to reduce water loss or deter herbivores during darkness.

- Leaf Orientation: Certain plants can adjust the orientation of their leaves throughout the day to optimize light absorption or minimize heat stress. For example, some desert plants orient their leaves vertically during midday to reduce direct sun exposure.

A Deeper Dive: Adaptations Across Biomes

The specific adaptations a plant develops are often dictated by the unique challenges of its biome. Exploring these specialized strategies reveals the incredible diversity of life on Earth.

Desert Dwellers: Masters of Water Conservation

Desert plants face extreme heat and severe water scarcity. Their adaptations are primarily focused on water acquisition, storage, and conservation.

- Reduced Leaf Surface Area: Many desert plants have small leaves, or no leaves at all (like cacti, where stems perform photosynthesis), to minimize the surface area from which water can evaporate.

- Hairy Leaves: Some desert plants have fine hairs on their leaves. These hairs create a boundary layer of still air, reducing air movement over the leaf surface and thus decreasing water loss.

- Ephemeral Life Cycles: Annual desert plants rapidly complete their entire life cycle, from germination to seed production, during brief periods of rainfall, then lie dormant as seeds through long dry spells.

Aquatic Adaptations: Life in Water

Plants living in water, known as hydrophytes, face different challenges, such as oxygen availability, buoyancy, and light penetration.

- Aerenchyma: Many aquatic plants have specialized air-filled tissues called aerenchyma in their stems and roots. This provides buoyancy, allowing leaves to float on the surface for light, and facilitates oxygen transport to submerged parts.

- Floating Leaves: Water lilies have large, flat leaves that float on the water surface, maximizing their exposure to sunlight. Their stomata are typically located on the upper surface of the leaf.

- Finely Dissected Leaves: Submerged aquatic plants often have highly divided or ribbon-like leaves. This increases their surface area for absorbing dissolved gases and nutrients directly from the water, as well as reducing resistance to water currents.

Cold Climate Conquerors: Surviving the Freeze

Plants in arctic or alpine regions must contend with freezing temperatures, strong winds, and short growing seasons.

- Evergreen Leaves: Conifers, like pines and spruces, retain their needles year-round. These needles have a thick waxy cuticle and a small surface area, reducing water loss in cold, dry winds and allowing them to photosynthesize whenever temperatures permit.

- Dwarf Growth Forms: Many arctic plants grow low to the ground, forming cushions or mats. This protects them from harsh winds and allows them to benefit from the insulating layer of snow.

- Dark Pigmentation: Some alpine plants have dark pigments in their leaves or stems, which helps them absorb more solar radiation and warm up faster in cold environments.

Nutrient Scavengers: Thriving in Poor Soils

Where soil nutrients are scarce, plants have evolved ingenious ways to acquire essential elements.

- Carnivory: As mentioned, carnivorous plants like pitcher plants, sundews, and Venus flytraps have modified leaves that trap and digest insects, providing them with vital nitrogen and phosphorus.

- Nitrogen Fixation: Legumes form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria in their root nodules. These bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by the plant, enriching the soil in the process.

The Evolutionary Dance: How Adaptations Arise

Plant adaptations are not static; they are the result of a dynamic evolutionary process. Genetic mutations introduce new traits into a population. If a mutation provides an advantage in a particular environment, individuals with that trait are more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their genes. Over vast stretches of time, these advantageous traits become more common, leading to the development of complex adaptations and the diversification of plant life.

This continuous process of natural selection ensures that plants are always finely tuned to their surroundings, a testament to the power of evolution in shaping the living world.

Conclusion: A World of Ingenuity

The study of plant adaptations offers a profound appreciation for the resilience and ingenuity of life. Every leaf, root, and flower tells a story of survival against the odds, a narrative of millions of years of evolutionary refinement. From the subtle tilt of a sunflower towards the sun to the intricate biochemistry of a cactus conserving water, plants demonstrate an unparalleled capacity to adapt and thrive.

Understanding these adaptations is not just an academic exercise; it is crucial for conservation efforts, agricultural innovation, and our broader understanding of ecosystem health. The plant kingdom, with its endless array of survival strategies, continues to inspire and educate, reminding us of the intricate beauty and profound interconnectedness of all living things.