Understanding Nonrenewable Resources: Earth’s Finite Treasures

Our planet provides an astonishing array of resources that sustain human civilization. From the air we breathe to the food we eat, life depends on these natural gifts. Among them, a crucial category stands out: nonrenewable resources. These are the Earth’s finite treasures, formed over geological timescales, and once consumed, they are gone for good or take millions of years to replenish. Understanding their nature, formation, and impact is paramount for our collective future.

What Exactly Are Nonrenewable Resources?

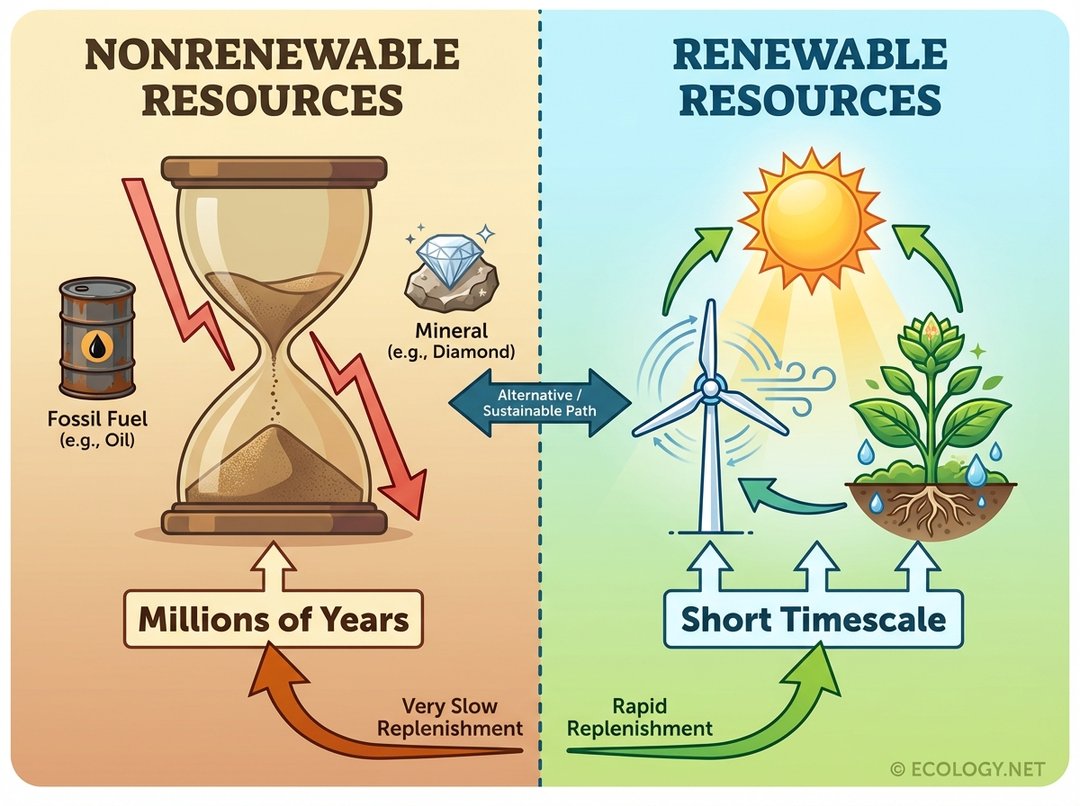

At its core, a nonrenewable resource is a natural substance that cannot be re-made, re-grown, or regenerated on a human timescale. While some might technically regenerate, the process is so incredibly slow, often spanning millions of years, that for all practical purposes, they are considered finite. This stands in stark contrast to renewable resources, like solar energy or timber, which replenish naturally and relatively quickly.

The defining characteristic of nonrenewable resources is their limited supply. Earth holds a fixed amount of these materials, and every time we extract and use them, we diminish that finite stock. This reality presents significant challenges for long-term sustainability and resource management.

The Big Four: Fossil Fuels

Perhaps the most well-known category of nonrenewable resources are the fossil fuels: coal, crude oil, and natural gas. These energy-rich substances have powered industrial revolutions, transportation, and electricity generation for centuries, fundamentally shaping modern society. Their immense energy content comes from ancient organic matter, transformed over eons.

How Fossil Fuels Are Formed: A Journey Through Geological Time

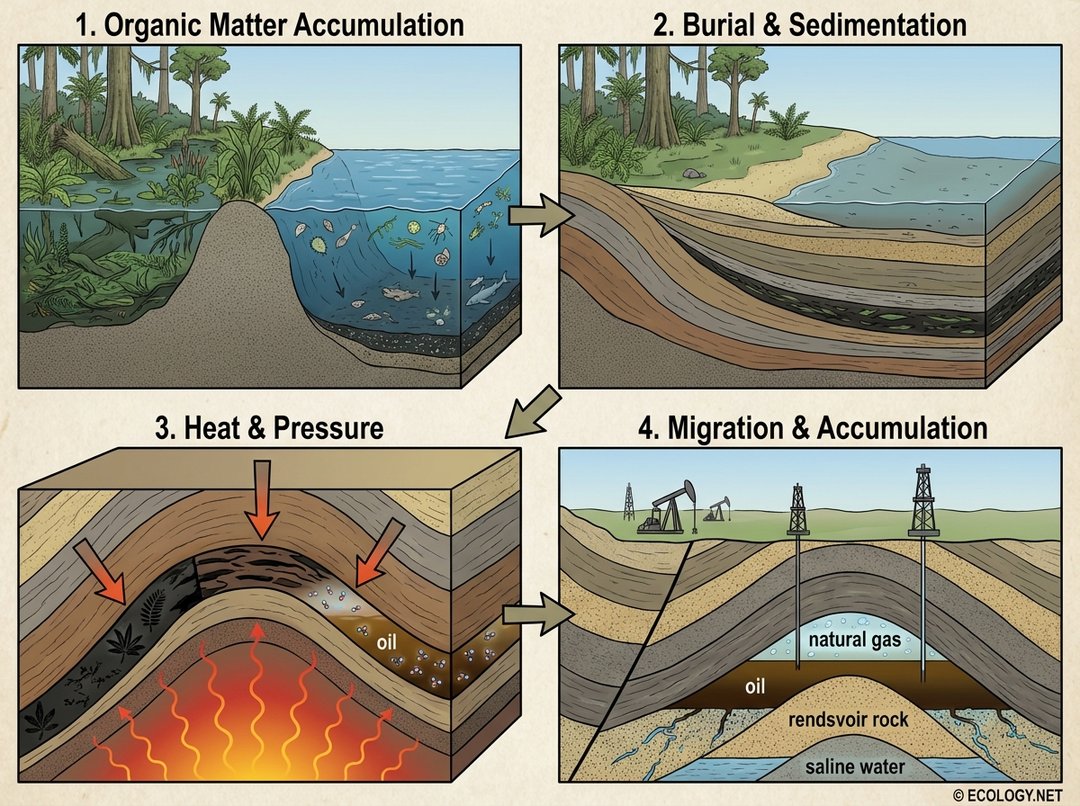

The creation of fossil fuels is a testament to Earth’s incredible geological processes, unfolding over vast stretches of time. It is a slow, complex transformation of organic material into the energy-dense substances we extract today.

The process typically involves four key stages:

- Organic Matter Accumulation: It all begins with the accumulation of vast quantities of organic material. For coal, this was primarily ancient plant matter from swamps and forests. For oil and natural gas, it was microscopic marine organisms and algae that settled on the ocean floor.

- Burial and Sedimentation: Over millions of years, layers of sediment, such as sand, silt, and clay, covered these organic deposits. The weight of these overlying layers compressed the organic matter, pushing out water and other volatile compounds.

- Heat and Pressure: As burial continued, the organic matter was subjected to increasing temperatures and pressures deep within the Earth’s crust. This intense heat and pressure, combined with bacterial action, chemically transformed the organic material into kerogen, a waxy substance. With further heat and pressure, kerogen broke down into hydrocarbons: crude oil and natural gas. For coal, the process of increasing heat and pressure transformed peat into lignite, then sub-bituminous coal, bituminous coal, and finally, anthracite.

- Migration and Accumulation: Once formed, oil and natural gas, being less dense than water, often migrated upwards through porous rock layers. They continued to move until they encountered an impermeable rock layer, which trapped them in underground reservoirs. Coal, being solid, remained in the rock layers where it formed.

This intricate process, requiring specific conditions and immense spans of time, underscores why fossil fuels are considered nonrenewable. We consume them far faster than nature can ever hope to create them.

Types of Fossil Fuels and Their Uses

Let us explore the primary types of fossil fuels:

- Coal: A solid, black, combustible sedimentary rock.

- Formation: Primarily from ancient plant matter in swampy environments.

- Uses: Historically, a dominant fuel for electricity generation and industrial processes like steel production.

- Impact: High carbon emissions when burned, contributing significantly to air pollution and climate change.

- Crude Oil (Petroleum): A viscous, dark liquid hydrocarbon mixture.

- Formation: From ancient marine organisms buried under sediment.

- Uses: Refined into gasoline for vehicles, diesel fuel, jet fuel, heating oil, and a vast array of petrochemicals used in plastics, pharmaceuticals, and synthetic materials.

- Impact: Combustion releases greenhouse gases, and oil spills can cause severe ecological damage.

- Natural Gas: A gaseous hydrocarbon mixture, primarily methane.

- Formation: Often found alongside crude oil, also from ancient marine organisms.

- Uses: Used for electricity generation, heating homes, industrial processes, and as a fuel for some vehicles.

- Impact: Burns cleaner than coal or oil, producing less carbon dioxide per unit of energy, but methane itself is a potent greenhouse gas, and leaks contribute to climate change.

Beyond Fossil Fuels: Minerals and Metals

While fossil fuels often dominate discussions about nonrenewable resources, another vital category includes minerals and metals. These inorganic substances are extracted from the Earth’s crust and are indispensable for construction, manufacturing, technology, and countless other applications. Like fossil fuels, their formation processes are geological and take millions of years, making them finite.

Essential Minerals and Metals

The diversity of minerals and metals is vast, each with unique properties and uses:

- Metallic Minerals: These are sources of metals that are vital for industry.

- Iron: The backbone of modern infrastructure, used in steel for buildings, bridges, and vehicles.

- Copper: Excellent electrical conductor, essential for wiring, electronics, and plumbing.

- Aluminum: Lightweight and strong, used in aircraft, cans, and construction.

- Gold, Silver, Platinum: Precious metals used in jewelry, electronics, and as investments.

- Rare Earth Elements: A group of 17 elements critical for high-tech applications, including smartphones, electric vehicles, and renewable energy technologies.

- Non-Metallic Minerals: These are equally crucial, though often less glamorous.

- Sand and Gravel: Fundamental components of concrete and asphalt, used in construction and road building. They are among the most heavily extracted materials globally.

- Limestone: Used in cement production, agriculture, and as a building material.

- Phosphate: Essential for fertilizers, supporting global food production.

- Potash: Another key ingredient in agricultural fertilizers.

- Salt: Used in food preservation, chemical manufacturing, and de-icing roads.

The extraction of these minerals and metals often involves extensive mining operations, which can have significant environmental impacts, including habitat destruction, water pollution, and land degradation.

The Environmental and Societal Impact of Nonrenewable Resources

The widespread use of nonrenewable resources, while fueling progress, comes with substantial environmental and societal costs.

Environmental Consequences

- Climate Change: The combustion of fossil fuels releases vast quantities of greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide and methane, trapping heat in the atmosphere and leading to global warming and climate change.

- Air and Water Pollution: Burning fossil fuels releases pollutants like sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter, contributing to smog, acid rain, and respiratory illnesses. Mining operations can contaminate water sources with heavy metals and toxic chemicals.

- Habitat Destruction: Extraction activities, whether drilling for oil or open-pit mining for minerals, often involve clearing large areas of land, destroying ecosystems, and displacing wildlife.

- Land Degradation: Mining can leave behind vast scars on the landscape, including waste rock piles and tailings ponds, which can be difficult and costly to reclaim.

Societal Challenges

- Resource Depletion: As finite resources are consumed, their availability diminishes, potentially leading to scarcity, price volatility, and geopolitical tensions over remaining reserves.

- Energy Security: Nations heavily reliant on imported fossil fuels face vulnerabilities to supply disruptions and price fluctuations.

- Health Impacts: Pollution from fossil fuel use and mining can lead to increased rates of respiratory diseases, cancers, and other health problems in nearby communities.

Managing Our Nonrenewable Legacy: Towards a Sustainable Future

Given the finite nature and environmental impact of nonrenewable resources, responsible management is not merely an option, but a necessity. A multi-faceted approach is required to mitigate the challenges and transition towards a more sustainable future.

Conservation and Efficiency

Reducing our overall consumption of nonrenewable resources is a critical first step.

- Reduce: Minimizing demand for energy and products made from nonrenewable materials. This includes energy-efficient appliances, public transportation, and conscious consumer choices.

- Reuse: Extending the lifespan of products to reduce the need for new ones.

- Recycle: Recovering and reprocessing materials like metals and plastics to create new products, thereby reducing the need for virgin extraction. Recycling aluminum, for instance, uses significantly less energy than producing it from bauxite ore.

Transition to Renewable Energy

Shifting away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources is perhaps the most impactful strategy for addressing climate change and resource depletion. Solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal power offer clean, continuously replenishing alternatives for electricity generation.

Sustainable Mining and Extraction Practices

For the nonrenewable resources we continue to need, adopting more sustainable extraction practices is vital. This includes:

- Minimizing environmental disturbance during mining.

- Implementing stricter pollution controls.

- Rehabilitating mined lands to restore ecosystems.

- Developing technologies for more efficient extraction and processing to reduce waste.

Innovation and Substitution

Investing in research and development to find alternative materials and technologies can reduce our reliance on scarce nonrenewable resources. For example, developing new battery chemistries that use less rare earth elements or creating bio-based plastics to replace petroleum-derived ones.

Conclusion

Nonrenewable resources have been the bedrock of human progress, providing the energy and materials that built our modern world. However, their finite nature and the significant environmental consequences of their extraction and use present humanity with one of its greatest challenges. By understanding their origins, impacts, and the imperative for responsible management, we can collectively work towards a future that balances our needs with the Earth’s capacity, ensuring that these finite treasures are managed wisely for generations to come. The journey towards sustainability is complex, but by embracing conservation, efficiency, and innovation, we can forge a path that honors our planet and secures our future.