Imagine a world where the very air we breathe holds the key to life, yet that key is locked away, inaccessible. This is the curious paradox of nitrogen. While it makes up a staggering 78% of Earth’s atmosphere, this abundant element, in its atmospheric form (N2), is largely unusable by most living organisms. It is a vital building block for proteins, DNA, and countless other essential biomolecules, yet plants and animals cannot simply absorb it from the air. This is where a miraculous process called nitrogen fixation steps in, acting as nature’s alchemist, transforming inert atmospheric nitrogen into life-sustaining forms.

The Essence of Nitrogen Fixation: Unlocking Life’s Building Block

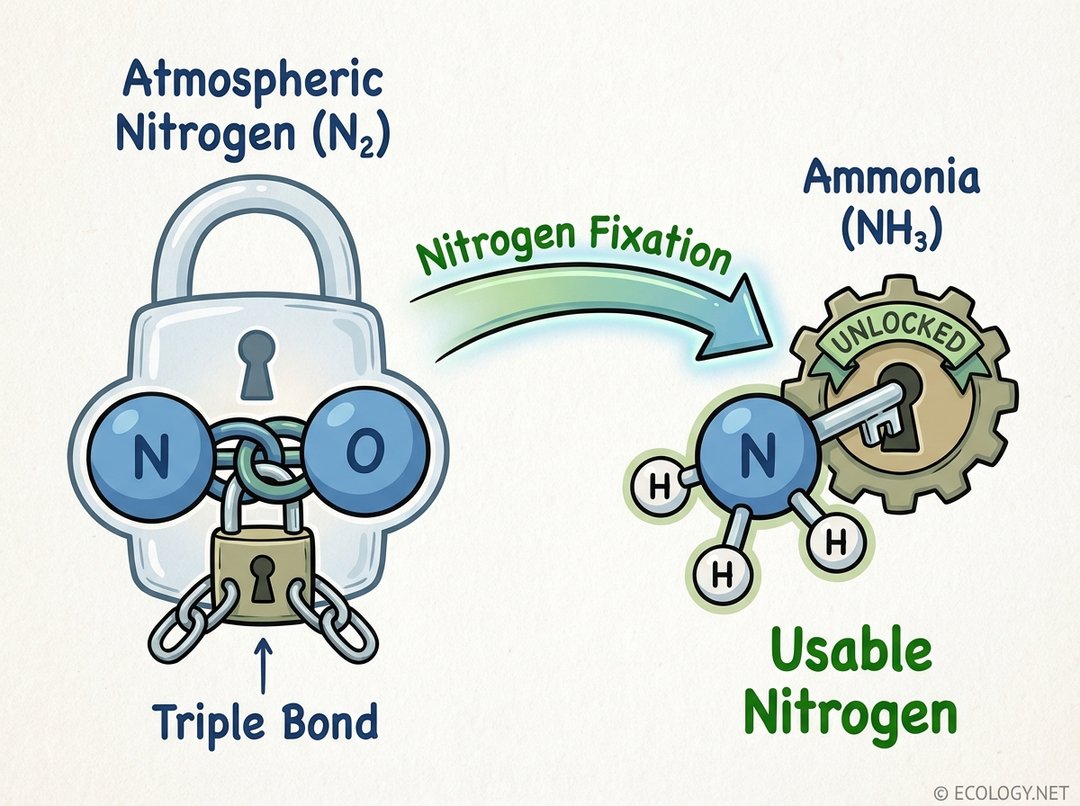

At the heart of the nitrogen paradox lies the incredibly strong triple bond that holds two nitrogen atoms together in atmospheric N2. This bond requires immense energy to break, rendering the molecule chemically inert and unavailable for biological processes. Nitrogen fixation is the process that breaks this formidable bond, converting atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia (NH3) or other nitrogen compounds that can be readily used by living organisms.

Think of it as unlocking a treasure chest. Atmospheric nitrogen is the locked chest, full of potential but inaccessible. Nitrogen fixation provides the key, transforming it into a usable form like ammonia, which plants can then absorb and incorporate into their tissues. Without this crucial conversion, life as we know it would simply not exist, as the fundamental building blocks for growth and reproduction would be missing.

Why is Nitrogen Fixation So Important?

The significance of nitrogen fixation cannot be overstated. It is the primary natural pathway by which atmospheric nitrogen enters the biosphere, becoming available to support all forms of life. Its importance spans across multiple domains:

- For Plants: Nitrogen is a macronutrient, essential for photosynthesis, chlorophyll production, and the synthesis of amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins. Without fixed nitrogen, plants cannot grow, develop, or produce seeds.

- For Animals: Animals obtain their nitrogen by consuming plants or other animals. Therefore, the availability of fixed nitrogen at the base of the food web directly impacts the health and survival of all animal life.

- For Ecosystems: Nitrogen fixation drives primary productivity in many ecosystems, particularly in nutrient-poor environments. It underpins the entire food web, from microscopic bacteria to towering trees and large mammals.

- For Agriculture: Modern agriculture heavily relies on fixed nitrogen to maximize crop yields. Understanding and harnessing nitrogen fixation is crucial for sustainable food production.

Who are the Fixers? The Agents of Transformation

Nitrogen fixation is not a single process but rather a collection of mechanisms carried out by various agents, both biological and abiotic.

Biological Nitrogen Fixation: Nature’s Tiny Chemists

The vast majority of nitrogen fixation on Earth is carried out by microorganisms, primarily bacteria and archaea, which possess a unique enzyme complex called nitrogenase. This enzyme is capable of breaking the strong triple bond of N2, a feat that requires a significant amount of energy and an oxygen-free environment, as nitrogenase is highly sensitive to oxygen.

Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation: A Partnership for Life

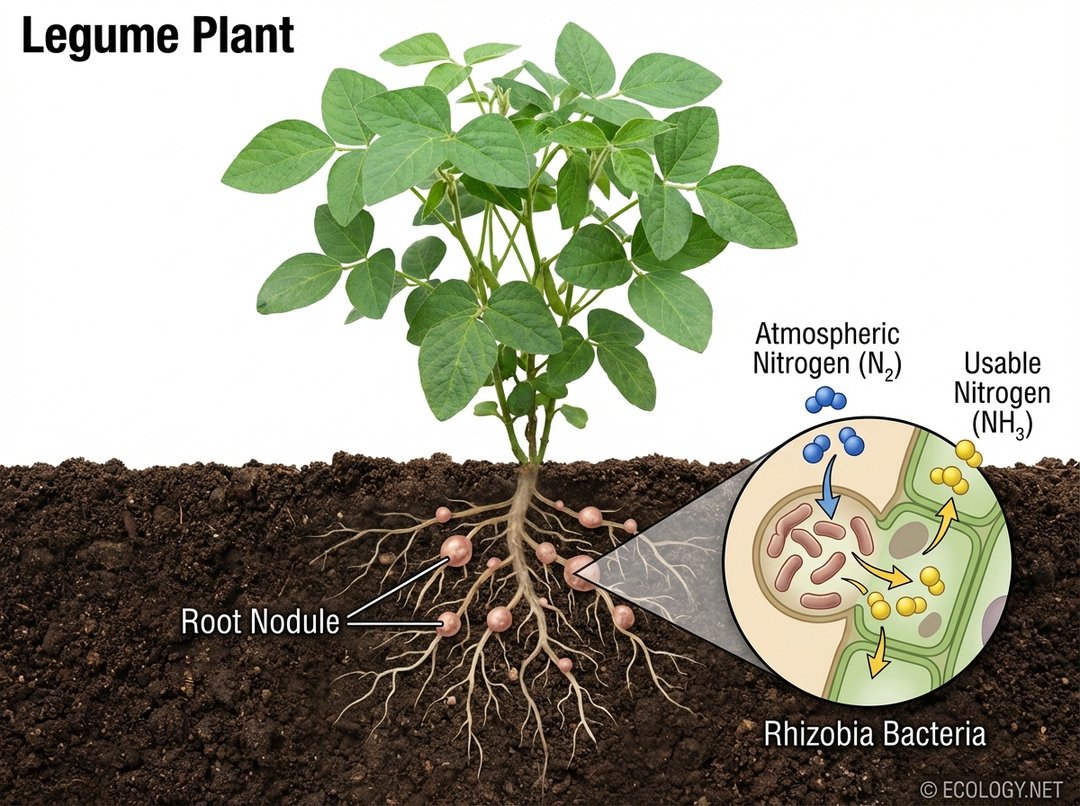

The most well-known and agriculturally significant form of biological nitrogen fixation occurs through a symbiotic relationship between certain plants and bacteria. Leguminous plants, such as soybeans, peas, clover, and alfalfa, form a remarkable partnership with a group of bacteria known as Rhizobia.

- The Partnership: Rhizobia bacteria infect the roots of legume plants, inducing the formation of specialized structures called root nodules. Within these nodules, the bacteria are protected from oxygen and provided with carbohydrates by the plant. In return, the Rhizobia fix atmospheric nitrogen, converting it into ammonia, which the plant readily absorbs and uses for growth.

- Mutual Benefits: This is a classic example of mutualism. The plant receives a vital nutrient it cannot obtain on its own, while the bacteria receive a protected habitat and a steady supply of energy. This natural fertilization process significantly enriches the soil with nitrogen, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers.

Free-Living Nitrogen Fixers

Beyond the symbiotic relationships, many free-living bacteria and archaea in soil and aquatic environments also contribute to nitrogen fixation. These include:

- Cyanobacteria (Blue-Green Algae): Found in diverse environments, from oceans to freshwater and soil, cyanobacteria are significant nitrogen fixers, especially in aquatic ecosystems and rice paddies.

- Azotobacter and Clostridium: These are common genera of free-living nitrogen-fixing bacteria found in soil. Azotobacter are aerobic (require oxygen), while Clostridium are anaerobic (thrive without oxygen).

Abiotic Nitrogen Fixation: Non-Biological Pathways

While biological processes dominate, nitrogen can also be fixed through non-biological means:

- Lightning: The immense energy of lightning bolts can break the triple bond of atmospheric nitrogen, allowing it to react with oxygen to form nitrogen oxides (NOx). These compounds dissolve in rainwater and fall to the Earth, contributing a small but significant amount of fixed nitrogen to ecosystems.

- Industrial Nitrogen Fixation (Haber-Bosch Process): Developed in the early 20th century, the Haber-Bosch process is a human-engineered method to fix nitrogen. It combines atmospheric nitrogen with hydrogen under high temperature and pressure to produce ammonia. This process is incredibly energy-intensive but revolutionized agriculture, enabling the mass production of synthetic fertilizers that feed billions of people worldwide.

Nitrogen Fixation’s Place in the Grand Nitrogen Cycle

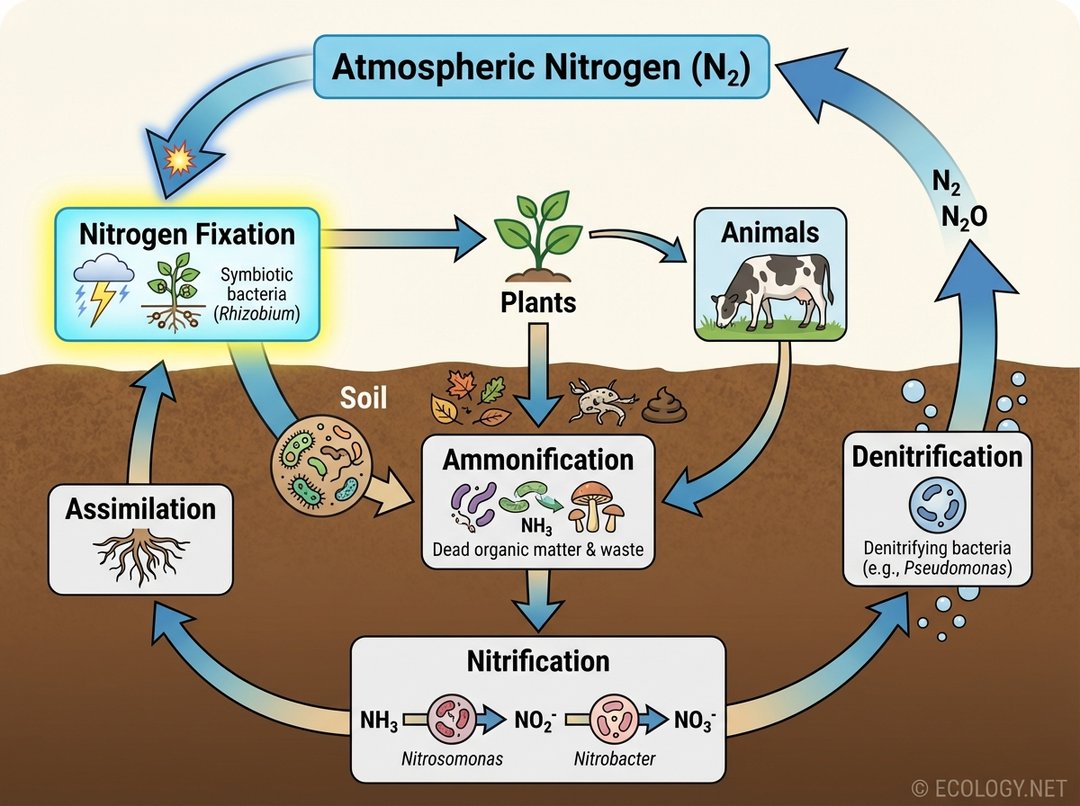

Nitrogen fixation is not an isolated event but the crucial entry point for nitrogen into the larger nitrogen cycle, a complex biogeochemical cycle that describes the movement of nitrogen through the Earth’s atmosphere, biosphere, and geosphere. Understanding this cycle is key to appreciating the interconnectedness of life and Earth systems.

The nitrogen cycle involves several key steps:

- Nitrogen Fixation: Atmospheric N2 is converted into ammonia (NH3) or ammonium (NH4+). This is the initial step that makes nitrogen available.

- Ammonification: When plants and animals die, or when animals excrete waste, decomposers (bacteria and fungi) convert organic nitrogen back into ammonia or ammonium.

- Nitrification: A two-step process where specific bacteria convert ammonium into nitrites (NO2–) and then into nitrates (NO3–). Nitrates are the most readily absorbed form of nitrogen for many plants.

- Assimilation: Plants absorb ammonia, ammonium, or nitrates from the soil and incorporate them into their own organic molecules (proteins, DNA). Animals then assimilate nitrogen by consuming plants or other animals.

- Denitrification: Under anaerobic conditions, another group of bacteria converts nitrates back into atmospheric nitrogen (N2) or nitrous oxide (N2O), completing the cycle by returning nitrogen to the atmosphere.

Nitrogen fixation is the critical entry point, constantly replenishing the supply of usable nitrogen that is otherwise lost back to the atmosphere through denitrification.

Ecological and Agricultural Significance: Balancing Act

The balance of nitrogen fixation and denitrification is crucial for maintaining healthy ecosystems. In natural environments, nitrogen fixation ensures a continuous supply of nutrients, supporting biodiversity and ecosystem productivity.

The ability of certain plants to host nitrogen-fixing bacteria is a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture, offering a natural alternative to synthetic fertilizers.

In agriculture, harnessing biological nitrogen fixation is a powerful tool:

- Crop Rotation: Farmers often rotate nitrogen-fixing legumes with non-leguminous crops (like corn or wheat). The legumes enrich the soil with nitrogen, benefiting the subsequent crop and reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers.

- Cover Cropping: Planting legumes as cover crops during off-seasons helps to improve soil health, prevent erosion, and naturally add nitrogen to the soil.

- Reduced Environmental Impact: Relying more on biological nitrogen fixation can lessen the environmental burden associated with synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, such as runoff into waterways causing eutrophication, and the emission of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas.

However, the widespread use of industrial nitrogen fixation has also led to challenges. While it has dramatically increased food production, the excess application of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers can lead to environmental problems, including water pollution, soil acidification, and increased greenhouse gas emissions. This highlights the delicate balance required in managing this essential element.

Conclusion: A Fundamental Process for Life

Nitrogen fixation, whether carried out by microscopic bacteria, the raw power of lightning, or sophisticated industrial processes, is a fundamental process that underpins all life on Earth. It transforms an inert atmospheric gas into the very building blocks of proteins and DNA, making it available to plants, and subsequently, to all other living organisms.

From the tiny root nodules of a clover plant to the vast expanse of the global nitrogen cycle, this process is a testament to nature’s ingenuity and the intricate web of life. Understanding nitrogen fixation is not just an academic exercise; it is crucial for sustainable agriculture, environmental stewardship, and appreciating the profound interconnectedness of our planet’s living systems. It reminds us that even the most abundant elements require a special touch to unlock their life-giving potential.