The Invisible Engine of Life: Understanding the Nitrogen Cycle

Imagine a world without proteins, DNA, or even the vibrant green of plants. It is a stark thought, but without one crucial element, life as we know it would simply not exist. That element is nitrogen, and its journey through our planet’s ecosystems is known as the nitrogen cycle. Far from being a simple process, this intricate ballet of chemical transformations and biological interactions is an invisible engine, powering everything from the smallest microbe to the largest whale.

Nitrogen is an abundant element, making up about 78% of Earth’s atmosphere. However, in its atmospheric gaseous form (N2), it is largely unusable by most living organisms. It is like having a vast ocean of water that you cannot drink. The nitrogen cycle is the natural process that converts this atmospheric nitrogen into various forms that can be utilized by plants and animals, and then returns it to the atmosphere, ensuring a continuous supply for life.

The Grand Tour: Stages of the Nitrogen Cycle

The nitrogen cycle is a complex series of steps, each vital for the overall balance. Let us embark on a grand tour of these transformations.

1. Nitrogen Fixation: Bringing Nitrogen Down to Earth

The first and arguably most critical step is nitrogen fixation. This is the process where atmospheric nitrogen (N2) is converted into ammonia (NH3), a form that can be used by living organisms. There are two primary ways this happens:

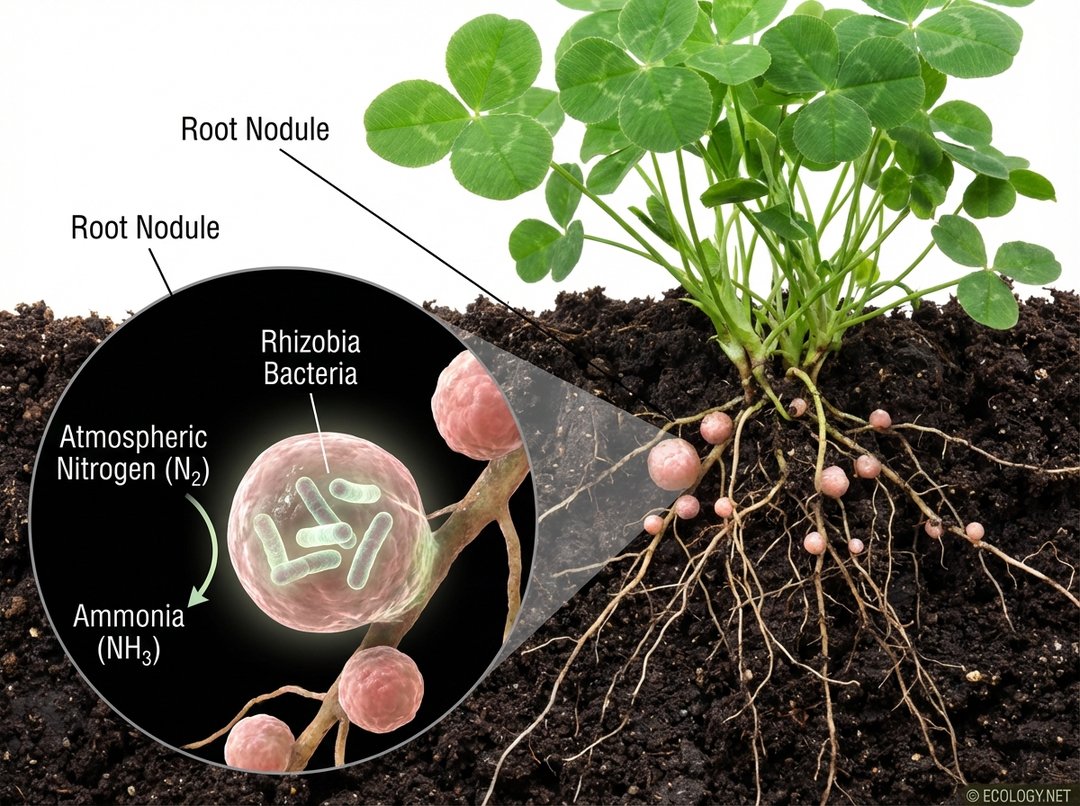

- Biological Fixation: This is carried out by specialized microorganisms, primarily bacteria. Some are free-living in the soil, while others form symbiotic relationships with plants. A classic example is the Rhizobia bacteria, which live in nodules on the roots of legume plants like peas, beans, and clover. These bacteria have the unique ability to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, providing the plant with a direct source of this essential nutrient. In return, the plant supplies the bacteria with carbohydrates.

- Atmospheric Fixation: Lightning strikes provide the immense energy needed to break the strong triple bond in atmospheric nitrogen molecules. This allows nitrogen to combine with oxygen, forming nitrogen oxides, which dissolve in rainwater and fall to the Earth as nitrates.

This illustration visually explains the crucial initial step of nitrogen fixation, specifically highlighting the symbiotic relationship between legumes and bacteria, a key example discussed in the article.

2. Nitrification: A Two-Step Conversion

Once ammonia (NH3) is present in the soil, either from fixation or decomposition, it undergoes nitrification. This is a two-step process performed by different groups of bacteria:

- Ammonia to Nitrite: Nitrifying bacteria, such as Nitrosomonas, convert ammonia (NH3) or ammonium (NH4+) into nitrites (NO2-).

- Nitrite to Nitrate: Other nitrifying bacteria, like Nitrobacter, then convert these nitrites into nitrates (NO3-). Nitrates are the most readily usable form of nitrogen for most plants.

3. Assimilation: Life Absorbs Nitrogen

With nitrates now available in the soil, plants can absorb them through their roots. This process is called assimilation. Once inside the plant, nitrates are converted into organic nitrogen compounds, such as amino acids, proteins, and nucleic acids (DNA and RNA). When animals consume plants, they assimilate these organic nitrogen compounds into their own bodies, building their tissues and carrying out vital functions.

4. Ammonification: Recycling Organic Nitrogen

When plants and animals die, or when animals excrete waste, the organic nitrogen compounds within their bodies are returned to the soil. Decomposers, primarily bacteria and fungi, break down this dead organic matter. This process, called ammonification, releases ammonia (NH3) or ammonium (NH4+) back into the soil, making it available for nitrification or direct uptake by some plants and microorganisms.

5. Denitrification: Returning Nitrogen to the Atmosphere

The final stage of the cycle is denitrification. This process is carried out by denitrifying bacteria, which thrive in anaerobic (oxygen-poor) conditions, often found in waterlogged soils. These bacteria convert nitrates (NO3-) back into gaseous atmospheric nitrogen (N2), completing the cycle and releasing nitrogen back into the atmosphere. This step is crucial for preventing an excessive buildup of nitrogen in ecosystems.

This image provides a comprehensive overview of all the interconnected stages of the nitrogen cycle, making it easier for readers to grasp the entire process described in the article.

Why is Nitrogen So Indispensable?

The continuous cycling of nitrogen is not just a biological curiosity; it is fundamental to life. Here is why nitrogen is so important:

- Building Blocks of Life: Nitrogen is a key component of amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins. Proteins perform countless functions in the body, from enzymes that catalyze reactions to structural components like muscle and hair.

- Genetic Material: Nitrogen is also an essential part of nucleic acids, DNA and RNA, which carry genetic information and direct protein synthesis. Without nitrogen, the blueprint of life itself could not exist.

- Photosynthesis: In plants, nitrogen is a vital component of chlorophyll, the pigment responsible for capturing sunlight energy during photosynthesis. A lack of nitrogen leads to yellowing leaves and stunted growth.

- Energy Transfer: Nitrogen is found in ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the primary energy currency of cells.

Human Impact: Disrupting the Delicate Balance

For millennia, the nitrogen cycle operated in a relatively stable balance. However, human activities have dramatically altered this natural equilibrium, primarily since the industrial revolution and the advent of synthetic fertilizers.

- Synthetic Fertilizers: The Haber-Bosch process, developed in the early 20th century, allowed for the industrial production of ammonia, which is used to create synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. While these fertilizers have revolutionized agriculture and helped feed a growing global population, their overuse has severe environmental consequences.

- Fossil Fuel Combustion: Burning fossil fuels in vehicles and power plants releases nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere, contributing to acid rain and smog.

- Livestock Farming: Animal waste from large-scale livestock operations also contributes significant amounts of nitrogen to the environment.

Consequences of Nitrogen Overload

The excess nitrogen introduced into ecosystems by human activities leads to several critical environmental problems:

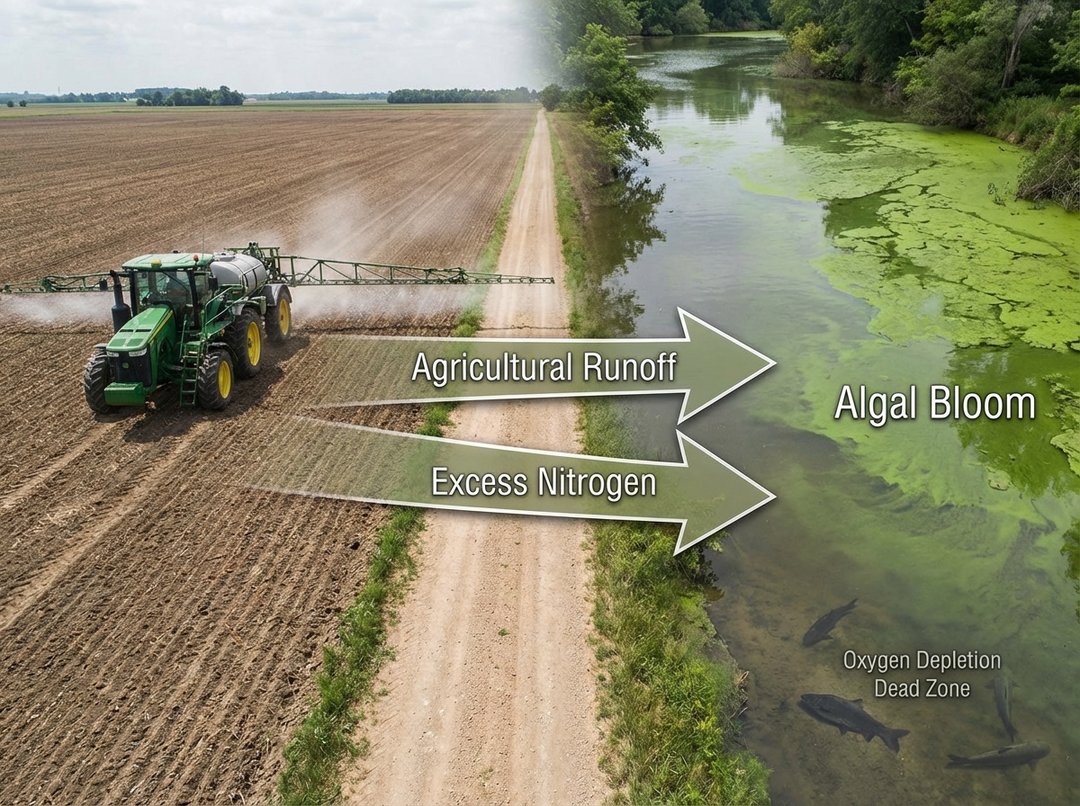

- Eutrophication: When excess nitrogen from agricultural runoff or sewage enters aquatic ecosystems (lakes, rivers, coastal waters), it acts as a super-fertilizer. This causes rapid and excessive growth of algae and aquatic plants, a phenomenon known as an “algal bloom.”

- Dead Zones: As these algal blooms eventually die, decomposers consume them, using up vast amounts of dissolved oxygen in the water. This leads to hypoxia (low oxygen) or anoxia (no oxygen), creating “dead zones” where most aquatic life, like fish and shellfish, cannot survive.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Denitrification in agricultural soils can release nitrous oxide (N2O), a potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change.

- Groundwater Contamination: Excess nitrates can leach into groundwater, contaminating drinking water supplies and posing health risks, particularly for infants.

This image vividly demonstrates the negative consequences of human-induced nitrogen excess, particularly eutrophication and dead zones, which are major environmental concerns detailed in the article.

Towards a Balanced Future: Managing Nitrogen

Understanding the nitrogen cycle is the first step towards mitigating human impact. Sustainable practices are crucial for restoring balance:

- Precision Agriculture: Applying fertilizers more efficiently, only when and where needed, reduces runoff.

- Cover Cropping and Crop Rotation: Using cover crops and rotating legumes can naturally enhance soil nitrogen without excessive synthetic inputs.

- Wastewater Treatment: Improving wastewater treatment facilities can reduce nitrogen discharge into aquatic systems.

- Reducing Fossil Fuel Use: Shifting to renewable energy sources can decrease atmospheric nitrogen oxide emissions.

Conclusion: The Unseen Thread of Life

The nitrogen cycle is a testament to the intricate interconnectedness of Earth’s systems. From the lightning bolt that fixes atmospheric nitrogen to the microscopic bacteria that return it to the sky, every step is a vital part of the planet’s life support system. As we continue to advance technologically, our understanding of these fundamental ecological processes becomes ever more critical. By respecting and working with the natural rhythms of the nitrogen cycle, rather than against them, we can ensure a healthier planet for all living things, safeguarding the invisible engine that powers life itself.