Imagine a scorching summer day. You step out into the blazing sun, feeling the heat radiate from the pavement. But then, you duck under the canopy of a large, leafy tree, and suddenly, the air feels noticeably cooler, perhaps even a little breezier. Or consider a frosty morning where the valley bottom is covered in a thick layer of ice, while the hillside just a few meters higher remains untouched. These everyday observations are not just quirks of weather; they are vivid demonstrations of a fundamental ecological concept: the microclimate.

A microclimate refers to the localized atmospheric conditions that differ significantly from the general climate of the surrounding area. These miniature climates can exist over areas as small as a few square centimeters, like the space under a rock, or extend over several square kilometers, such as a large urban center. They are shaped by a fascinating interplay of factors, creating pockets of unique temperature, humidity, wind, and light conditions that profoundly influence the life within them.

What is a Microclimate?

At its core, a microclimate is a small-scale variation in climate. While a region might have a broad climate classification, like “temperate” or “arid,” within that region, countless tiny environments exist, each with its own distinct climatic fingerprint. Think of it as the difference between looking at a country on a map versus exploring a specific neighborhood within a city. The broad strokes tell you one story, but the finer details reveal a much richer, more complex picture.

These localized differences are often dramatic. A patch of bare soil exposed to direct sunlight will absorb and radiate heat far more intensely than a shaded area covered by dense vegetation. Similarly, the air near a body of water will typically be more humid than air over dry land. These variations are not random; they are predictable outcomes of how energy, moisture, and air move through specific landscapes.

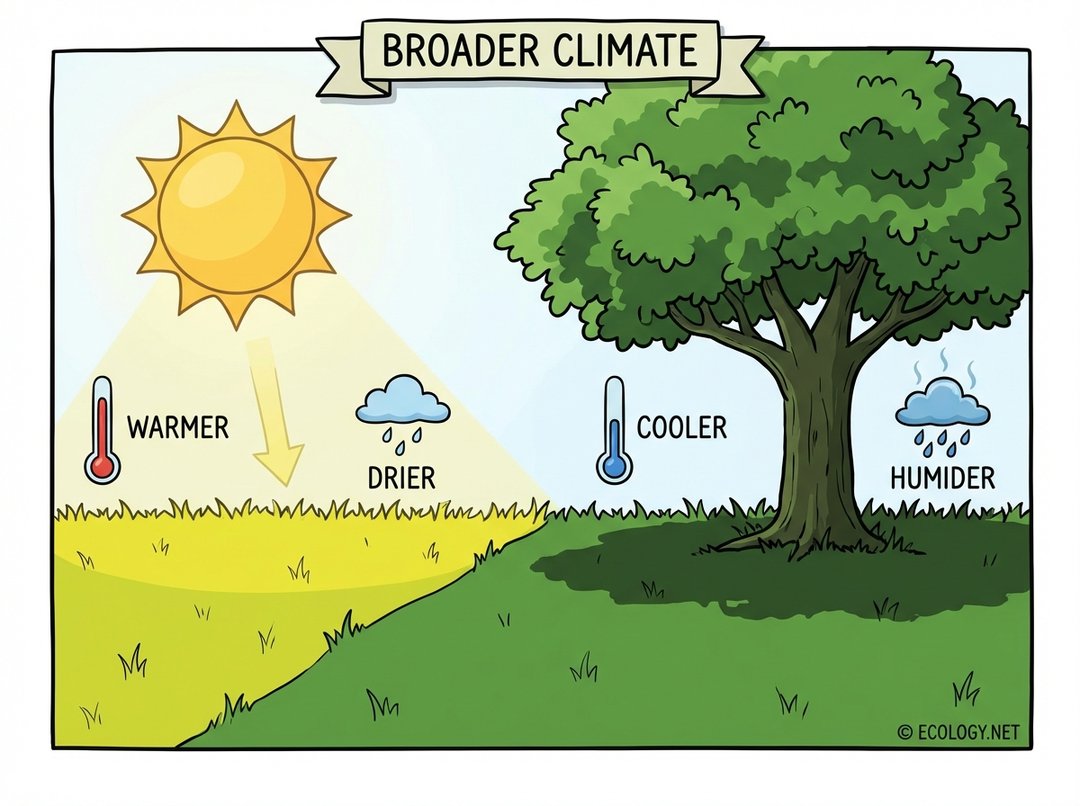

The image above beautifully illustrates this concept. On one side, a sun-drenched patch of grass experiences warmer, drier conditions. On the other, the deep shadow of a tree creates a cooler, more humid environment. Both exist within the same broader climate, yet their immediate atmospheric conditions are strikingly different. This simple contrast highlights how easily microclimates form and how significant their impact can be.

Factors Shaping Microclimates

Microclimates are not accidental; they are the direct result of specific environmental factors interacting with incoming solar radiation and atmospheric processes. Understanding these factors is key to appreciating the complexity and importance of these localized climates.

Topography and Landform

The shape of the land plays a crucial role in determining how much sunlight an area receives, how air flows, and where moisture collects.

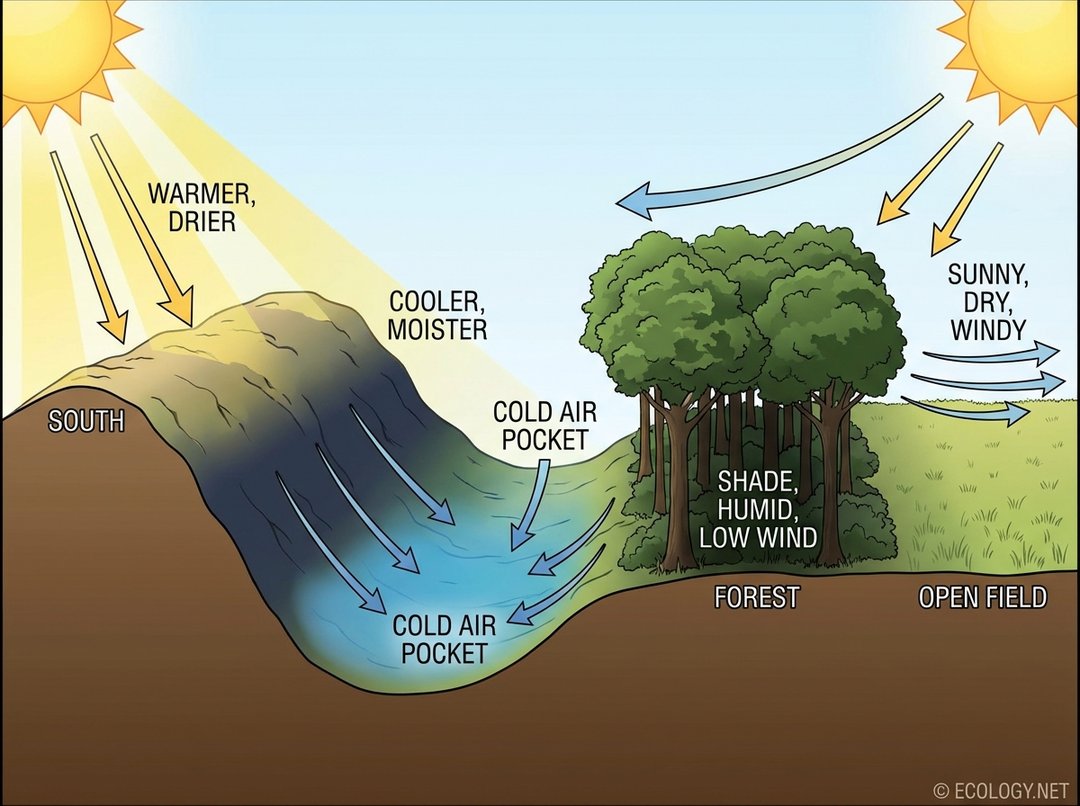

- Slope Aspect: The direction a slope faces significantly impacts its microclimate. In the Northern Hemisphere, south-facing slopes receive more direct sunlight, making them generally warmer and drier. North-facing slopes, conversely, receive less direct sun, remaining cooler and often moister. This difference can lead to entirely different plant communities thriving on opposite sides of the same hill.

- Elevation: Temperature generally decreases with increasing elevation. Higher altitudes experience cooler temperatures, stronger winds, and often more precipitation.

- Valleys and Depressions: Cold air is denser than warm air, causing it to sink and accumulate in low-lying areas like valleys and depressions. This phenomenon creates “frost pockets” where temperatures can drop significantly lower than on surrounding hillsides, making these areas particularly susceptible to frost damage, even in otherwise mild regions.

Vegetation and Surface Cover

What covers the ground has a profound effect on how energy is absorbed, reflected, and released.

- Forest Canopies: Dense forests create a distinct microclimate beneath their canopy. The leaves intercept sunlight, reducing light intensity on the forest floor. They also transpire water, increasing humidity, and slow down wind speeds. The result is a cooler, more humid, and less windy environment compared to an open field.

- Open Fields and Grasslands: These areas are fully exposed to the sun and wind. They tend to be warmer during the day, drier, and experience greater temperature fluctuations between day and night.

- Water Bodies: Lakes, rivers, and oceans moderate temperatures. Water heats up and cools down more slowly than land, leading to cooler summers and warmer winters in adjacent areas. They also contribute moisture to the air, increasing local humidity.

- Soil and Rock: Darker soils absorb more solar radiation, becoming warmer. Rocky outcrops can also heat up significantly, creating warm microclimates. Conversely, light-colored sands reflect more sunlight, staying relatively cooler.

Artificial Structures and Urbanization

Human-made structures dramatically alter natural microclimates, often creating entirely new ones.

- Buildings and Pavement: Concrete, asphalt, and building materials absorb and store a large amount of solar radiation, releasing it slowly, especially at night. This contributes to the “Urban Heat Island” effect, where cities are significantly warmer than surrounding rural areas.

- Walls and Fences: A south-facing wall can create a warm, sheltered microclimate, ideal for growing heat-loving plants. A tall fence can block wind, creating a calm zone behind it.

The diagram above clearly illustrates how these factors combine. We see the stark contrast between a warm, dry south-facing slope and a cool, moist north-facing slope. A valley bottom collects cold air, forming a distinct pocket. Adjacent to these topographical features, a dense forest creates a shaded, humid, low-wind environment, while an open field is sunny, dry, and windy. These visual examples underscore the power of topography and vegetation in shaping the local climate.

Common Examples of Microclimates

Microclimates are all around us, often unnoticed but constantly influencing our environment.

- The Shade of a Tree: Perhaps the most common example. Under a tree, temperatures can be several degrees cooler, and humidity higher, than in direct sunlight. This provides refuge for animals and allows shade-loving plants to thrive.

- South-Facing Walls: In many gardens, a wall facing the sun can create a significantly warmer microclimate, extending the growing season for certain fruits and vegetables or allowing the cultivation of plants that would otherwise struggle in the local climate.

- Urban Heat Islands: Cities, with their vast expanses of concrete, asphalt, and buildings, absorb and retain much more heat than surrounding rural areas. This leads to higher temperatures in urban centers, especially at night, a phenomenon known as the Urban Heat Island effect. This can impact energy consumption, air quality, and human health.

The image above vividly depicts the Urban Heat Island effect. On one side, a bustling city glows with a red overlay, indicating higher temperatures due to heat absorption by urban surfaces. On the other, a serene rural landscape with lush greenery shows a cooler, blue overlay. This stark visual contrast makes the impact of urbanization on local climates undeniable.

- Coastal Microclimates: Areas near large bodies of water often experience milder temperatures, higher humidity, and specific wind patterns (like sea breezes) that differ from inland regions just a few kilometers away.

- Under a Rock or Log: For small creatures like insects, amphibians, and fungi, the space under a rock or log provides a crucial microclimate. It offers protection from extreme temperatures, maintains higher humidity, and shields from direct sunlight and wind.

- Inside a Greenhouse: A greenhouse is a deliberately created microclimate, designed to trap solar energy and maintain higher temperatures and humidity for plant growth, regardless of external conditions.

Why Do Microclimates Matter?

The existence of microclimates is far from a mere academic curiosity; it has profound implications across various fields.

Ecology and Biodiversity

- Species Distribution: Microclimates dictate where specific plants and animals can survive and thrive. A particular insect might only be found on the north-facing side of a hill, or a rare orchid might require the precise humidity and light conditions found in a forest understory.

- Habitat Creation: Diverse microclimates within a larger area increase habitat diversity, supporting a wider range of species and contributing to overall biodiversity.

- Ecological Niches: Microclimates create unique ecological niches, allowing different species to coexist by utilizing slightly different environmental conditions.

Agriculture and Horticulture

- Crop Selection: Farmers and gardeners strategically choose crops suited to the microclimates of their land. For example, frost-sensitive crops are avoided in known frost pockets.

- Site Selection: Understanding microclimates helps in selecting optimal sites for vineyards, orchards, or specific vegetable patches to maximize yield and quality.

- Pest and Disease Management: Microclimatic conditions can influence the prevalence of pests and diseases. Humid microclimates, for instance, might favor fungal growth.

- Frost Protection: Knowledge of cold air drainage helps in designing landscapes or employing strategies to protect plants from damaging frosts.

Urban Planning and Architecture

- Green Infrastructure: Urban planners use green spaces, parks, and tree planting to mitigate the Urban Heat Island effect, creating cooler, more pleasant microclimates within cities.

- Building Design: Architects consider local microclimates when designing buildings, orienting them to maximize natural light and ventilation, or to provide shade and shelter from prevailing winds.

- Pedestrian Comfort: Creating comfortable microclimates in public spaces, through shading, water features, and windbreaks, enhances the quality of urban life.

Human Comfort and Health

- Outdoor Activities: Our choice of where to sit, walk, or relax outdoors is often an intuitive response to microclimates, seeking shade on a hot day or a sheltered spot on a windy one.

- Heat Stress: In urban areas, extreme heat exacerbated by the Urban Heat Island effect can pose significant health risks, especially for vulnerable populations.

Measuring and Studying Microclimates

Scientists, gardeners, and urban planners employ various tools and techniques to measure and understand microclimates.

- Thermometers and Data Loggers: Simple thermometers provide spot readings, while electronic data loggers can continuously record temperature, humidity, and other parameters over time, providing valuable insights into daily and seasonal fluctuations.

- Anemometers: These devices measure wind speed, helping to identify sheltered or exposed areas.

- Hygrometers: Used to measure relative humidity, crucial for understanding moisture levels in different microclimates.

- Light Sensors: Measure light intensity, important for assessing shade levels and their impact on plant growth.

- Transects and Grids: Researchers often set up a series of sensors along a transect (a line across a landscape) or in a grid pattern to map microclimatic variations across an area.

- Remote Sensing and Modeling: Satellite imagery and aerial photography, combined with sophisticated computer models, can help map larger-scale microclimatic patterns, especially in urban areas or complex terrain.

Conclusion

Microclimates are a testament to the intricate dance between the sun, the atmosphere, and the Earth’s varied surfaces. They remind us that climate is not a monolithic entity but a dynamic tapestry woven from countless localized conditions. From the cool, damp earth beneath a fallen log to the sweltering concrete canyons of a city, these miniature climates shape ecosystems, influence human endeavors, and add a layer of fascinating complexity to our world.

By understanding microclimates, we gain a deeper appreciation for the natural world and acquire practical knowledge that can inform everything from sustainable agriculture to resilient urban design. The next time you feel a sudden change in temperature or a gentle breeze in an unexpected spot, pause and consider the hidden microclimate at play. It is a subtle yet powerful force, constantly at work, shaping the world around us in ways both grand and minute.