The natural world is a tapestry of interconnected life, where species have evolved over millennia to fit specific niches within their native ecosystems. However, a silent, often unseen threat is unraveling this delicate balance across the globe: invasive species. These biological invaders are not merely exotic curiosities; they represent a profound challenge to biodiversity, ecosystem health, and even human economies.

Understanding the Invader: What are Invasive Species?

The term “invasive species” is frequently used, but its precise meaning can sometimes be misunderstood. It is crucial to distinguish between a species that is simply present outside its native range and one that poses a significant threat.

Introduced, Non-Native, and Invasive: A Clarification

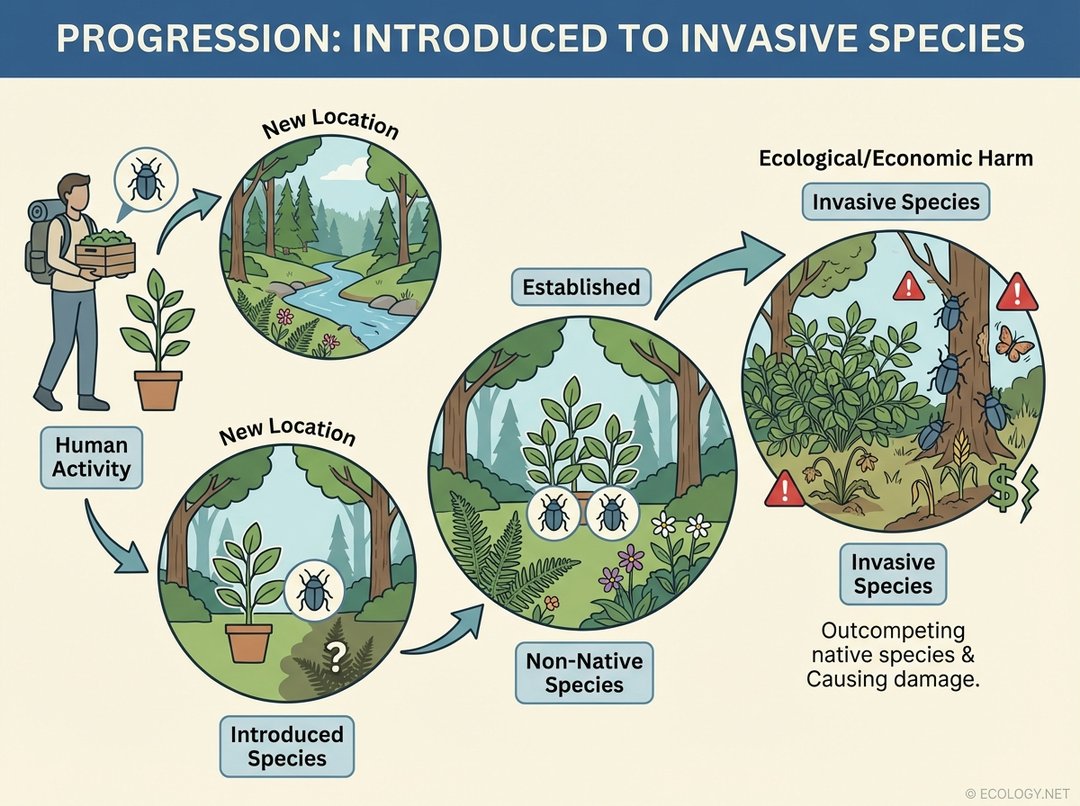

- Introduced Species: Any species that has been moved by human activity, intentionally or accidentally, to a new geographic area outside its historical range. Not all introduced species become problematic.

- Non-Native (or Exotic/Alien) Species: This term is synonymous with “introduced species.” It simply denotes that the species is not indigenous to a particular area. Many non-native species coexist harmlessly with native flora and fauna.

- Invasive Species: This is the critical distinction. An invasive species is a non-native species whose introduction causes, or is likely to cause, economic or environmental harm or harm to human health. The key here is the negative impact. Without demonstrable harm, a non-native species is not considered invasive.

To visualize this progression from a harmless newcomer to a destructive force, consider the following illustration:

Why Do Invasive Species Matter? The Ecological and Economic Impact

The consequences of invasive species are far-reaching, affecting every corner of the planet and every aspect of human society. Their impact can be devastating, often leading to irreversible changes.

Ecological Devastation: A Threat to Biodiversity

Invasive species are considered one of the leading drivers of biodiversity loss worldwide, second only to habitat destruction. Their methods of disruption are varied and potent:

- Predation: New predators can decimate native populations that have not evolved defenses against them. Island ecosystems, in particular, are highly vulnerable.

- Competition: Invaders often outcompete native species for vital resources like food, water, light, and space. They may grow faster, reproduce more rapidly, or tolerate a wider range of conditions.

- Disease Transmission: Invasive species can introduce novel pathogens or parasites to native populations, which lack immunity, leading to widespread disease and mortality.

- Habitat Alteration: Some invasive plants can drastically change the physical structure of an ecosystem, altering fire regimes, nutrient cycles, or water availability, making it unsuitable for native species.

- Hybridization: Invasive species can sometimes interbreed with closely related native species, leading to hybrids that dilute the genetic integrity of the native population.

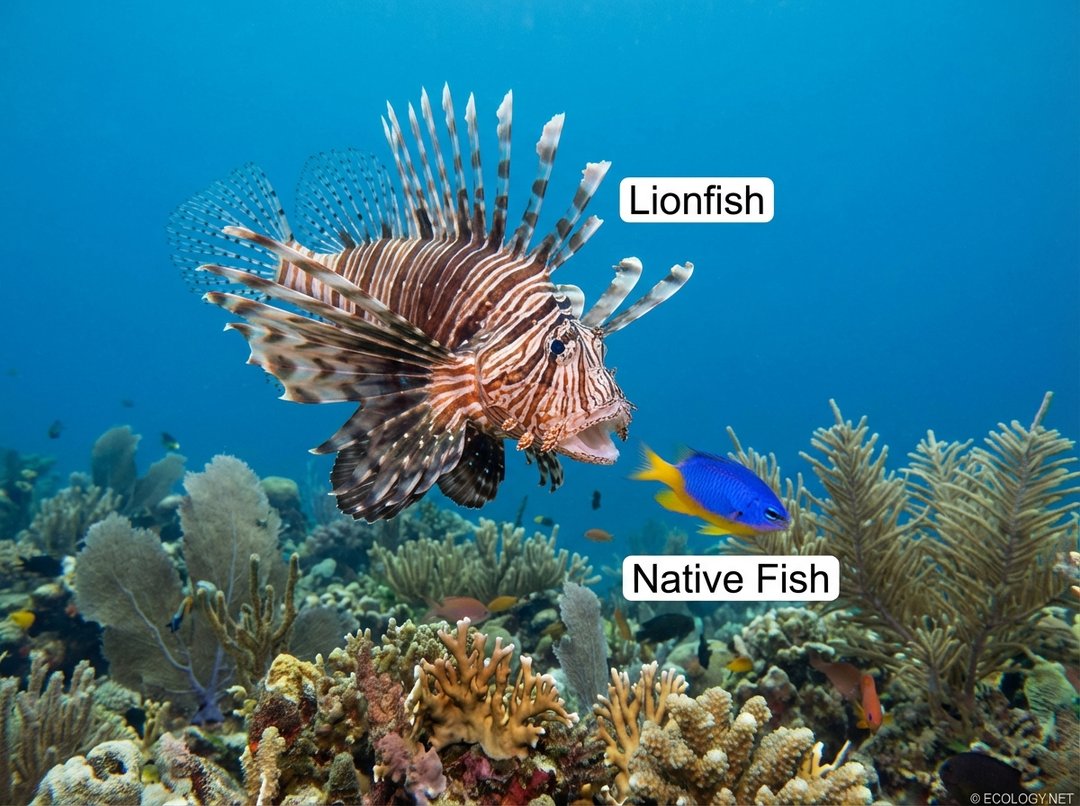

A prime example of a voracious invader is the lionfish, a beautiful yet deadly predator in Atlantic waters.

Lionfish, native to the Indo-Pacific, have rapidly spread throughout the Western Atlantic, Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico. With no natural predators in these new environments and a prodigious appetite, they consume vast quantities of native reef fish and invertebrates, disrupting delicate food webs and threatening the health of coral reefs.

Economic Burdens: Costly Consequences

Beyond ecological harm, invasive species impose immense economic costs globally. These costs stem from:

- Agricultural Losses: Invasive weeds, pests, and diseases can devastate crops and livestock, leading to reduced yields and increased management expenses.

- Fisheries Decline: Aquatic invaders can outcompete or prey on commercially important fish species, impacting fishing industries.

- Infrastructure Damage: Some species can clog waterways, damage power lines, or undermine foundations of buildings and roads.

- Forestry Impacts: Invasive insects and pathogens can destroy vast tracts of forests, impacting timber industries and ecosystem services.

- Public Health: Certain invasive species can act as vectors for human diseases or cause allergic reactions.

- Management and Control: Significant financial resources are required for monitoring, eradication, and control efforts.

How Do Species Become Invasive? Pathways of Introduction

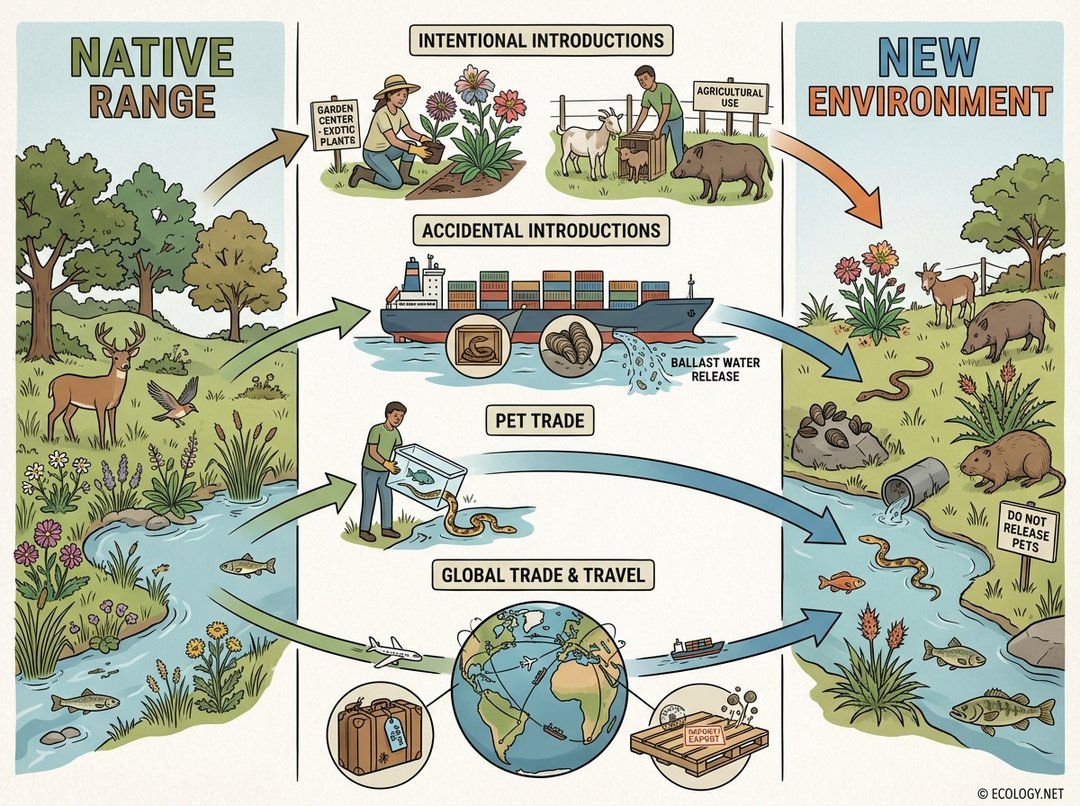

The vast majority of invasive species introductions are directly or indirectly linked to human activities. As global trade, travel, and population movements increase, so does the risk of new invasions. Understanding these pathways is crucial for prevention.

Primary Pathways of Introduction

- Intentional Introductions:

- Agriculture and Aquaculture: Species are introduced for food production, pest control, or as ornamental plants. For instance, the kudzu vine was brought to the U.S. to control soil erosion.

- Horticulture and Landscaping: Many popular garden plants are non-native and can escape cultivation to become invasive.

- Sport and Recreation: Game animals or fish are sometimes introduced for hunting or fishing purposes.

- Biological Control: While intended to control other pests, some introduced biological control agents have themselves become invasive.

- Accidental Introductions (Stowaways):

- Shipping and Transportation:

- Ballast Water: Ships take on ballast water in one port and discharge it in another, releasing countless marine organisms. Zebra mussels, a notorious freshwater invader in North America, are believed to have arrived this way.

- Cargo: Insects, seeds, and other organisms can hitchhike in shipping containers, on pallets, or within goods. The Emerald Ash Borer, which has devastated ash trees across North America, likely arrived in wood packing materials.

- Travel and Tourism: Seeds or spores can cling to clothing, shoes, or vehicles, transported unknowingly across vast distances.

- Shipping and Transportation:

- Pet Trade and Escapes:

- Exotic pets, aquarium fish, or plants purchased for home use can escape or be intentionally released into the wild when owners can no longer care for them. The Burmese python, now a major threat in the Florida Everglades, is a prime example of a pet trade escapee.

- Global Trade and Travel:

- The sheer volume and speed of modern global commerce and human movement create unprecedented opportunities for species to cross geographical barriers. This overarching category encompasses many of the specific pathways listed above, highlighting the interconnectedness of the modern world.

Common Examples of Invasive Species Across Ecosystems

The problem of invasive species is not confined to a single type of organism or environment. It is a global phenomenon affecting terrestrial, aquatic, and even aerial ecosystems.

- Zebra Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha): These small freshwater mollusks, native to Eastern Europe, have colonized vast areas of North American waterways. They filter massive amounts of water, altering food webs, and attach to virtually any hard surface, clogging pipes and damaging infrastructure.

- Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata): Known as “the vine that ate the South,” this fast-growing plant from Asia was introduced to the southeastern U.S. for erosion control. It smothers native vegetation, trees, and even buildings, creating monocultures.

- Burmese Python (Python bivittatus): Released or escaped from the pet trade, these large constrictors have established breeding populations in the Florida Everglades. They are apex predators, decimating native mammal and bird populations.

- Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis): This iridescent green beetle, native to Asia, has killed tens of millions of ash trees across North America. Its larvae tunnel under the bark, disrupting the tree’s ability to transport water and nutrients.

- Cane Toad (Rhinella marina): Introduced to Australia to control sugarcane pests, these highly toxic toads have become a devastating invasive species. Their poison kills native predators that attempt to eat them, and they compete with native amphibians for resources.

Characteristics of Successful Invaders: Why Some Species Thrive

Not every introduced species becomes invasive. A combination of traits in the invading species and conditions in the recipient ecosystem often determine success.

Traits of the Invader:

- Rapid Reproduction: High reproductive rates, short generation times, and effective dispersal mechanisms (e.g., prolific seed production, high fecundity).

- Generalist Nature: Ability to thrive in a wide range of environmental conditions and utilize diverse food sources, rather than being specialized.

- Lack of Natural Enemies: In their new environment, invaders often escape the predators, parasites, and diseases that kept their populations in check in their native range.

- High Dispersal Ability: Efficient mechanisms for spreading to new areas, whether by wind, water, or animal vectors.

- Phenotypic Plasticity: The ability to adjust their growth and development to suit varying environmental conditions.

- Pioneer Species Traits: Often good colonizers of disturbed habitats.

Characteristics of the Invaded Ecosystem:

- Disturbance: Ecosystems that have been disturbed by human activity (e.g., logging, agriculture, urbanization) are often more susceptible to invasion.

- Low Diversity: Ecosystems with fewer native species may have more open niches for invaders to exploit.

- Absence of Competitors or Predators: If the new environment lacks species that can effectively compete with or prey upon the invader, its population can explode unchecked.

Prevention and Management: What Can Be Done?

Addressing the invasive species crisis requires a multi-faceted approach, with prevention being the most cost-effective strategy.

Prevention: The First Line of Defense

- Strict Regulations and Inspections: Governments implement quarantine measures, inspect cargo, and regulate the import of plants and animals to prevent new introductions.

- Public Awareness and Education: Educating the public about responsible pet ownership, gardening choices, and cleaning boats/gear to prevent hitchhikers is vital. Campaigns like “Don’t Let It Loose” target pet and aquarium releases.

- Early Detection and Rapid Response (EDRR): Monitoring for new invaders and quickly implementing eradication efforts when a new population is detected can prevent widespread establishment.

Management Strategies: When Prevention Fails

Once an invasive species is established, management becomes more complex and costly, often involving a combination of methods:

- Eradication: Complete removal of an invasive population. This is usually only feasible for small, newly established populations.

- Control: Reducing the population of an invasive species to an acceptable level to minimize its impact. This often requires ongoing effort.

- Mechanical Control: Physical removal, such as hand-pulling weeds, trapping animals, or constructing barriers.

- Chemical Control: Use of herbicides for plants or pesticides for insects. This must be done carefully to avoid harming native species.

- Biological Control: Introducing a natural enemy (a predator, parasite, or pathogen) from the invader’s native range to control its population. This is a complex strategy requiring extensive research to ensure the biocontrol agent itself does not become invasive.

- Restoration: After invasive species are removed or controlled, efforts are often needed to restore native habitats and reintroduce native species.

Conclusion: A Shared Responsibility

Invasive species represent a profound and persistent challenge to the planet’s biodiversity and human well-being. From the subtle spread of a garden plant to the dramatic impact of a marine predator, these biological invasions underscore the interconnectedness of global ecosystems and the far-reaching consequences of human actions.

Understanding the pathways of introduction, the characteristics of successful invaders, and the devastating impacts they cause is the first step toward effective mitigation. While the scale of the problem can seem daunting, every individual has a role to play, whether through responsible choices in gardening and pet ownership, supporting conservation efforts, or advocating for stronger biosecurity measures. Protecting our native ecosystems from these silent invaders is a shared responsibility, essential for preserving the rich tapestry of life on Earth for future generations.