In the intricate dance of agriculture and land management, few tools have sparked as much discussion and innovation as herbicides. These chemical compounds, designed to control unwanted plant growth, have revolutionized food production, simplified landscaping, and shaped ecosystems across the globe. But what exactly are herbicides, how do they work, and what are the broader implications of their widespread use? Join us on a journey to unravel the science and ecology behind these powerful plant managers.

The Fundamental Divide: Selective vs. Non-Selective Herbicides

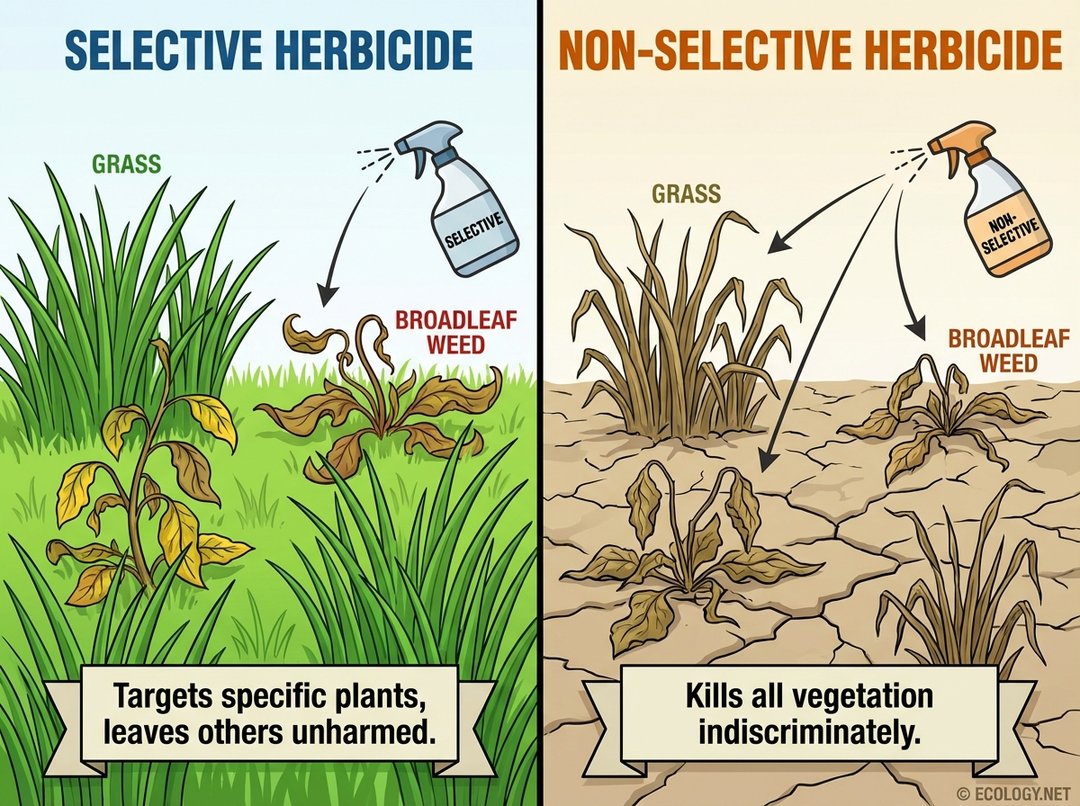

At its core, the world of herbicides can be understood through a primary distinction: whether they target specific plants or act indiscriminately. This fundamental difference dictates their application and impact.

Selective Herbicides: Precision Targeting

Imagine a surgeon carefully removing only the problematic tissue while leaving healthy cells untouched. Selective herbicides operate on a similar principle. These compounds are formulated to kill certain types of plants, typically weeds, while leaving desirable plants, such as crops or lawn grasses, unharmed. This selectivity is often achieved through differences in plant physiology, leaf shape, or metabolic pathways.

- Example: A common selective herbicide like 2,4-D is widely used in lawns to control broadleaf weeds like dandelions and clover, without harming the narrow-leafed grass. Farmers also rely on selective herbicides to protect their corn, wheat, or soybean crops from competing weeds.

Non-Selective Herbicides: Broad-Spectrum Action

In contrast, non-selective herbicides are the blunt instruments of weed control. They are designed to kill nearly all plant material they come into contact with, regardless of species. Their power lies in their ability to clear an area completely of vegetation.

- Example: Glyphosate, perhaps the most well-known non-selective herbicide, is frequently used to clear fence lines, prepare garden beds for planting, or eliminate all vegetation in a specific area before construction. It is also crucial in “no-till” farming systems, allowing farmers to kill weeds before planting without disturbing the soil.

Unveiling the Mechanisms: How Herbicides Disrupt Plant Life

Herbicides are not just generic plant killers. They are sophisticated chemicals that interfere with specific biochemical processes vital for plant survival. Understanding these “modes of action” is key to appreciating their effectiveness and the challenges they pose.

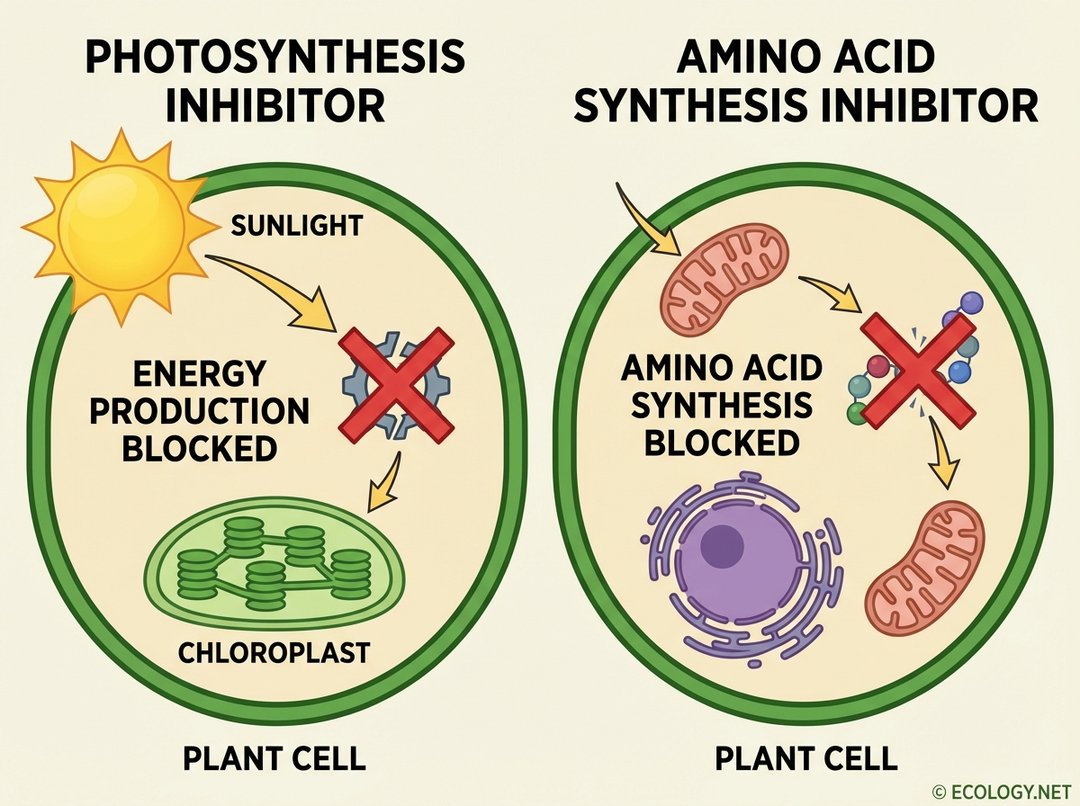

Interrupting Energy Production: Photosynthesis Inhibitors

Plants are masters of photosynthesis, converting sunlight into energy. Some herbicides target this fundamental process, effectively starving the plant. These compounds bind to specific sites within the chloroplasts, the plant’s energy factories, preventing the conversion of light energy into chemical energy.

- Mechanism: By blocking electron transport or disrupting pigment function, these herbicides cause a buildup of toxic byproducts, leading to cell damage and eventual plant death.

- Example: Herbicides like atrazine and diuron are classic examples of photosynthesis inhibitors, often used in agricultural settings to control a wide range of weeds.

Blocking Building Blocks: Amino Acid Synthesis Inhibitors

Amino acids are the fundamental building blocks of proteins, essential for every cellular function and growth. Another major class of herbicides works by inhibiting the synthesis of specific amino acids that plants need to survive. Animals, including humans, cannot synthesize these particular amino acids and must obtain them from their diet, which is why these herbicides are often considered to have low toxicity to mammals.

- Mechanism: These herbicides target specific enzymes involved in amino acid synthesis pathways, such as the EPSPS enzyme pathway inhibited by glyphosate, or the ALS enzyme pathway inhibited by sulfonylurea herbicides. Without these essential amino acids, plants cannot produce vital proteins, leading to stunted growth and death.

- Example: Glyphosate, a non-selective herbicide, works by inhibiting the EPSPS enzyme, crucial for the synthesis of aromatic amino acids. Sulfonylurea herbicides, often selective, inhibit the ALS enzyme, impacting branched-chain amino acid synthesis.

Other Modes of Action

Beyond these two major categories, herbicides employ a diverse array of strategies:

- Growth Regulators: These mimic natural plant hormones, causing uncontrolled and distorted growth that ultimately leads to the plant’s demise. 2,4-D is an example.

- Cell Membrane Disruptors: These herbicides cause rapid breakdown of cell membranes, leading to desiccation and necrosis.

- Lipid Synthesis Inhibitors: These prevent the formation of lipids, which are essential components of cell membranes and energy storage.

- Pigment Inhibitors: These block the production of chlorophyll and other pigments, leading to bleached plants that cannot photosynthesize.

The Evolutionary Challenge: Herbicide Resistance

While herbicides offer powerful solutions for weed control, their widespread and repeated use has inadvertently triggered one of the most significant ecological challenges in modern agriculture: herbicide resistance.

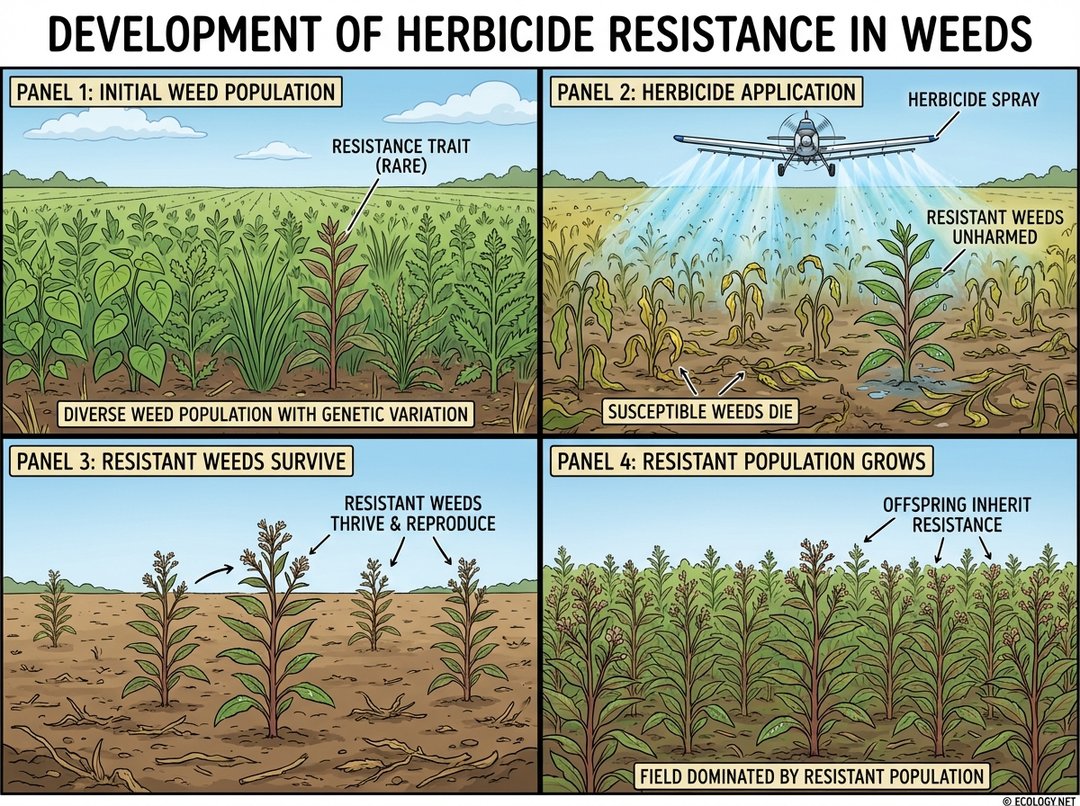

A Story of Natural Selection in Action

The development of herbicide resistance is a classic example of evolution by natural selection playing out in real time. It is not that herbicides cause mutations, but rather that they select for naturally occurring genetic variations within a weed population.

- Initial Weed Population: In any given field, a diverse population of weeds exists. Within this population, a tiny fraction of individual weeds may possess a natural genetic mutation that confers some level of tolerance or resistance to a particular herbicide, even if that herbicide has never been applied before.

- Herbicide Application: When an herbicide is applied, it effectively kills the vast majority of susceptible weeds. However, the few resistant individuals, by virtue of their genetic makeup, survive the treatment.

- Resistant Weeds Survive and Reproduce: With the competition from susceptible weeds eliminated, the resistant survivors thrive. They reproduce, passing on their resistance genes to their offspring.

- Resistant Population Grows: Over successive generations and repeated applications of the same herbicide or herbicides with the same mode of action, the proportion of resistant weeds in the field dramatically increases. Eventually, the herbicide becomes ineffective against the now dominant resistant weed population.

The Consequences of Resistance

Herbicide resistance poses significant threats:

- Increased Costs: Farmers must resort to more expensive herbicides, higher application rates, or alternative, often more labor-intensive, weed control methods.

- Reduced Crop Yields: Uncontrolled weeds can severely reduce crop yields, impacting food security and farmer livelihoods.

- Environmental Concerns: The need for stronger or more frequent herbicide applications can heighten environmental risks.

- Loss of Valuable Tools: When a herbicide becomes ineffective due to widespread resistance, a crucial tool for weed management is lost.

Beyond the Field: Environmental and Health Considerations

The ecological footprint of herbicides extends beyond the target weeds. Responsible use and careful consideration are paramount.

Environmental Impacts

- Off-Target Movement (Drift): Herbicides can drift from their intended application area, affecting non-target plants, sensitive ecosystems, and even adjacent crops.

- Water Contamination: Runoff from treated fields can carry herbicides into rivers, lakes, and groundwater, potentially impacting aquatic life and drinking water sources.

- Impact on Biodiversity: While targeting weeds, some herbicides can inadvertently harm beneficial insects, soil microorganisms, or other non-target plant species, reducing overall biodiversity.

Human Health and Safety

Regulatory bodies worldwide rigorously test and approve herbicides for use, setting strict guidelines for application and residue limits. When used according to label instructions, approved herbicides are generally considered safe. However, concerns persist regarding long-term exposure, particularly for agricultural workers, and the potential for residues in food. Adherence to safety protocols, including wearing personal protective equipment, is crucial for minimizing risks.

Towards a Sustainable Future: Integrated Weed Management

Recognizing the complexities and challenges associated with herbicides, modern ecological and agricultural practices increasingly advocate for Integrated Weed Management (IWM). IWM is a holistic approach that combines various strategies to control weeds effectively while minimizing reliance on chemical solutions.

- Cultural Practices:

- Crop Rotation: Alternating different crops breaks weed life cycles and prevents the buildup of specific weed populations.

- Cover Crops: Planting non-cash crops between growing seasons suppresses weeds, improves soil health, and reduces erosion.

- Optimized Planting Dates and Densities: Giving the desired crop a competitive advantage over weeds.

- Mechanical Control:

- Tillage: Physically disrupting weeds.

- Hand Weeding: Labor-intensive but highly effective for small areas.

- Mowing: Preventing weeds from going to seed.

- Biological Control:

- Using natural enemies, such as insects or pathogens, to suppress weed populations. This is often more effective in natural or rangeland settings.

- Chemical Control (Herbicides):

- Used judiciously and strategically as part of a broader plan.

- Rotation of Modes of Action: Alternating herbicides with different modes of action is critical to prevent or delay the development of resistance.

- Precision Application: Using technology to apply herbicides only where and when needed, reducing overall usage.

Conclusion: A Balanced Perspective on Herbicides

Herbicides are undeniably powerful tools that have played a pivotal role in shaping modern agriculture and land management. They have contributed significantly to increased food production, reduced labor, and enabled practices like no-till farming that benefit soil health. However, their use is not without ecological and evolutionary consequences, most notably the pervasive challenge of herbicide resistance.

As we move forward, a deeper understanding of herbicide science, their modes of action, and their environmental interactions becomes increasingly vital. The future of sustainable weed management lies not in the outright rejection or uncritical embrace of herbicides, but in their intelligent, integrated, and responsible use, guided by ecological principles and a commitment to long-term environmental health.