Imagine a world where every living thing exists in isolation, eating and being eaten in a simple, straight line. While this might sound like a neat way to organize nature, it is far from the truth. The reality is much more intricate, a vibrant tapestry of life where every organism is connected to many others in a complex dance of survival. This intricate network is what ecologists call a food web, and understanding it is key to grasping the very essence of life on Earth.

From Food Chains to Food Webs: Unraveling Nature’s Connections

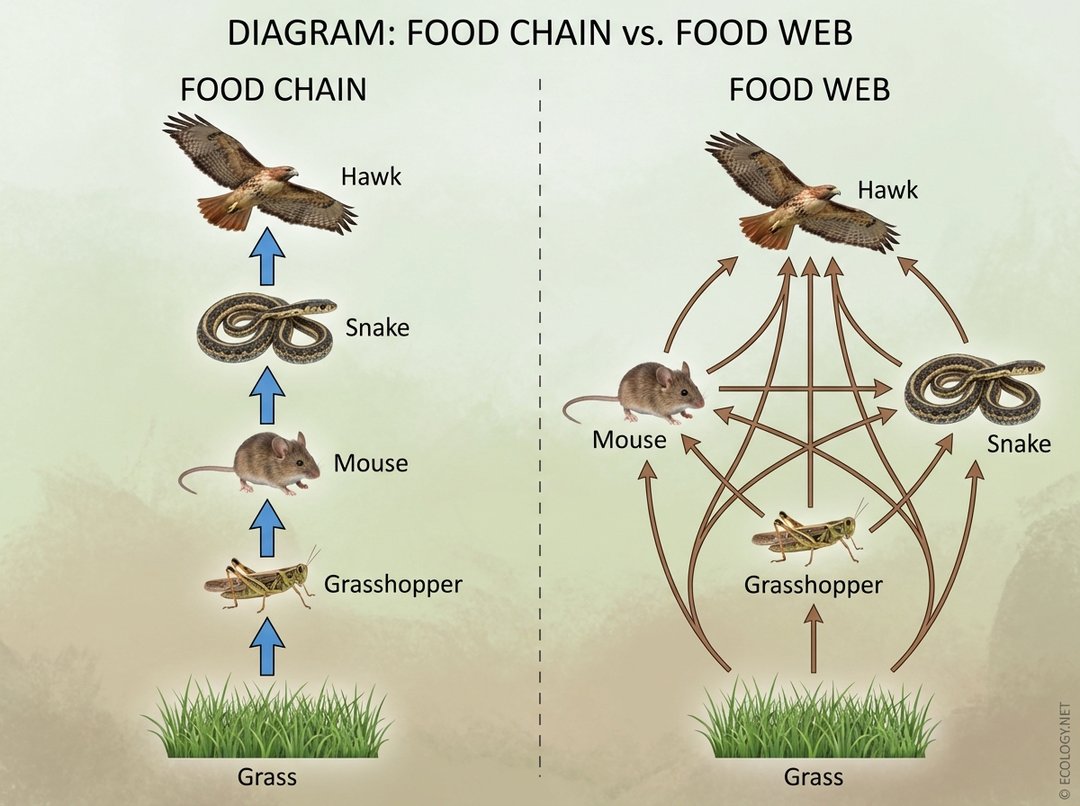

Most of us are familiar with the concept of a food chain. It is a straightforward model illustrating how energy flows from one organism to another. A classic example might be grass eaten by a grasshopper, which is then eaten by a mouse, then a snake, and finally a hawk. This linear progression is easy to visualize and helps introduce the basic idea of who eats whom.

However, nature is rarely so simple. A hawk does not solely eat snakes; it might also prey on mice, small birds, or even large insects. Similarly, a mouse does not only eat grasshoppers; it consumes seeds, fruits, and other plant matter. This is where the concept of a food web comes into play. A food web is essentially a collection of interconnected food chains, showing the myriad feeding relationships within an ecosystem. It paints a far more accurate and dynamic picture of energy transfer and interdependence.

Think of it like this: a food chain is a single strand of yarn, while a food web is a beautifully woven sweater, with countless threads crossing and intertwining. The complexity of a food web highlights the resilience and interconnectedness of an ecosystem. If one species disappears, others might have alternative food sources, allowing the web to adapt and persist, though not without consequences.

Key Players in the Web: Trophic Levels and Ecological Roles

To understand a food web, it is crucial to recognize the different roles organisms play. Ecologists categorize these roles into what are called “trophic levels,” which describe an organism’s position in the food web based on its primary source of energy. These levels are fundamental to how energy moves through an ecosystem.

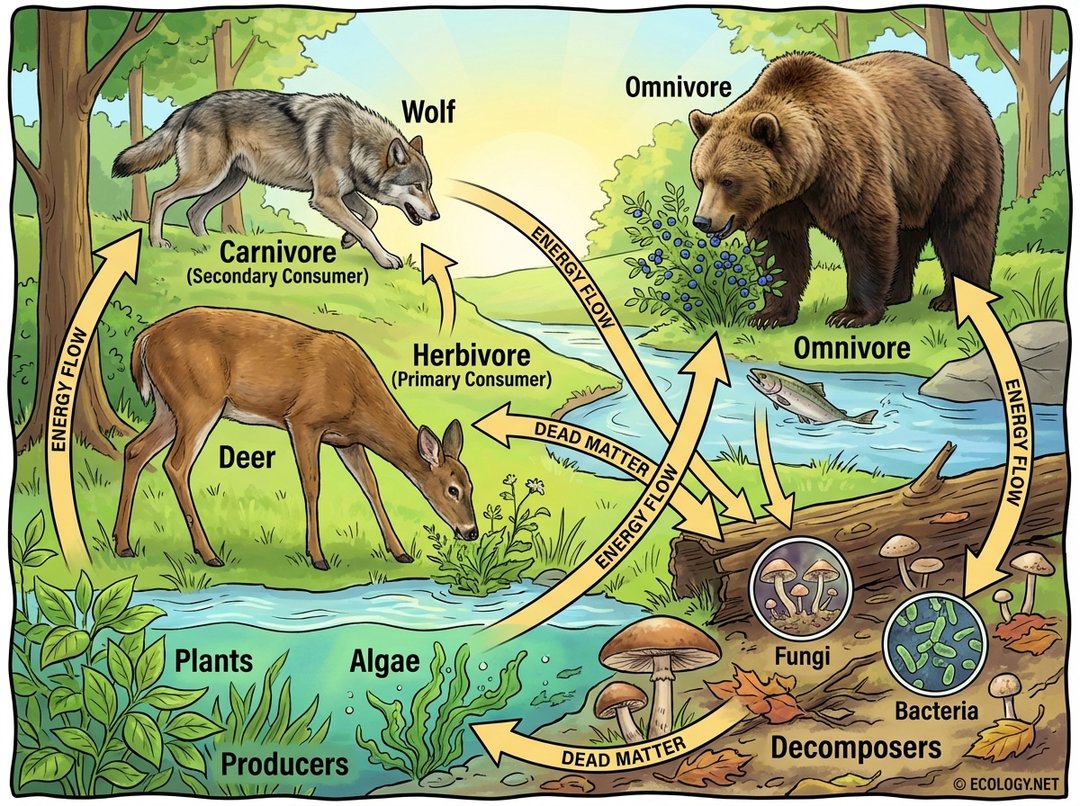

- Producers (Autotrophs): These are the foundation of nearly every food web. Producers, primarily plants, algae, and some bacteria, create their own food using energy from the sun through photosynthesis, or in rare cases, chemical reactions (chemosynthesis). They convert inorganic matter into organic compounds, making energy available to all other life forms.

- Consumers (Heterotrophs): Organisms that obtain energy by consuming other organisms. Consumers are further divided based on what they eat:

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): These organisms feed directly on producers. Examples include deer grazing on grass, rabbits eating clover, or caterpillars munching on leaves.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores or Omnivores): These organisms feed on primary consumers. A fox eating a rabbit, a snake eating a mouse, or a bird eating an insect are examples of secondary consumers.

- Tertiary Consumers (Carnivores or Omnivores): These organisms feed on secondary consumers. A hawk preying on a snake, or a large fish eating a smaller fish that ate zooplankton, are examples.

- Quaternary Consumers: In some complex food webs, there can be a fourth level of consumers that feed on tertiary consumers.

- Omnivores: Many animals do not fit neatly into a single consumer category. Omnivores, such as bears, humans, and raccoons, eat both plants and animals, occupying multiple trophic levels simultaneously.

- Decomposers (Detritivores): Often overlooked but absolutely vital, decomposers break down dead organic matter from all trophic levels. Fungi, bacteria, and various invertebrates like earthworms and millipedes return essential nutrients to the soil and water, making them available for producers to use again. Without decomposers, ecosystems would quickly become choked with waste, and nutrient cycles would grind to a halt.

Each of these roles is indispensable. The removal or significant reduction of any group can have cascading effects throughout the entire food web, demonstrating the delicate balance of nature.

The Flow of Life: Food Web Energetics

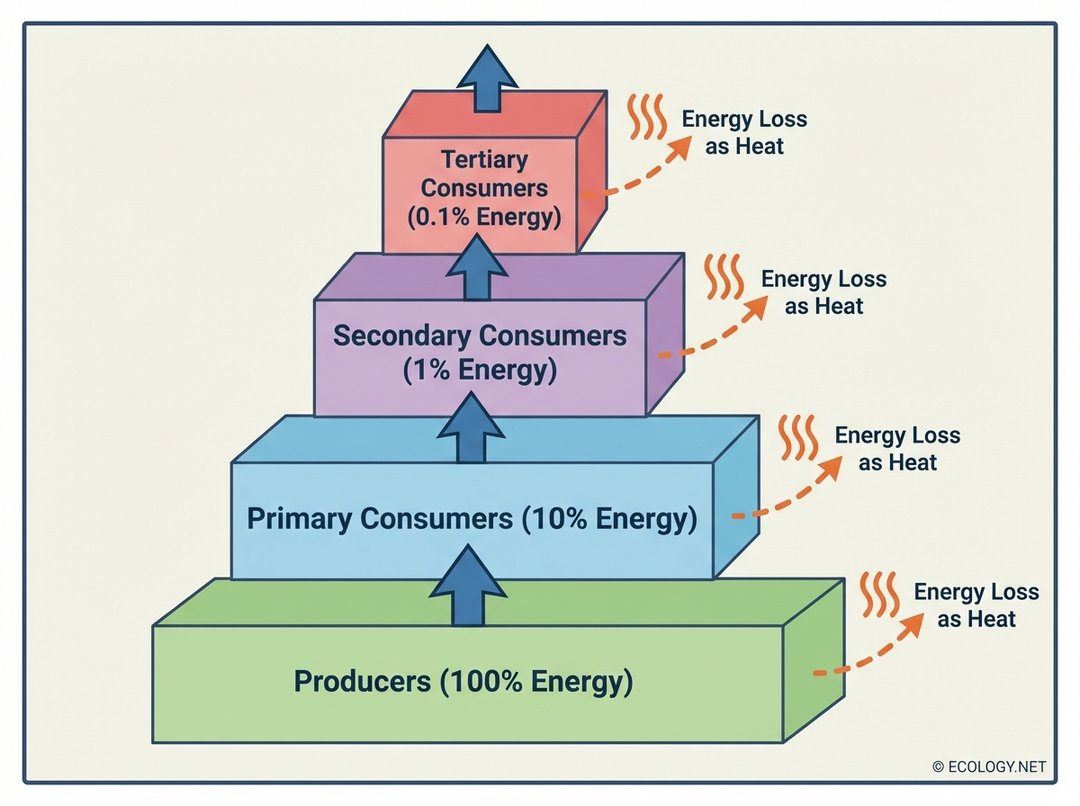

Energy is the driving force behind all life, and its movement through a food web is a fundamental concept in ecology. When one organism consumes another, energy is transferred, but this transfer is never 100% efficient. A significant portion of energy is lost at each step, primarily as heat, due to metabolic processes and incomplete consumption.

The 10% Rule: A Fundamental Principle

A widely accepted ecological principle, often referred to as the “10% rule,” states that on average, only about 10% of the energy from one trophic level is transferred to the next. The remaining 90% is lost to the environment, primarily as metabolic heat, or remains in uneaten or undigested parts of organisms.

This rule has profound implications for the structure of ecosystems:

- Limited Trophic Levels: It explains why most food webs rarely have more than four or five trophic levels. There simply is not enough energy left to support higher levels of consumers.

- Biomass Distribution: It dictates that there must be a much larger biomass of producers than primary consumers, a larger biomass of primary consumers than secondary consumers, and so on. This creates the characteristic pyramid shape seen in ecological pyramids of energy and biomass.

- Population Sizes: Similarly, the number of individuals generally decreases at higher trophic levels. It takes a vast number of plants to support a smaller number of herbivores, which in turn support an even smaller number of carnivores.

Consider a simple example: if producers capture 10,000 units of energy, primary consumers might only assimilate 1,000 units. Secondary consumers would then get only 100 units, and tertiary consumers a mere 10 units. This dramatic reduction in available energy at each step underscores the importance of the base of the food web.

Why Food Webs Matter: Beyond Simple Eating

Understanding food webs extends far beyond simply knowing who eats whom. These intricate networks are critical for comprehending ecosystem stability, biodiversity, and even the impact of human activities.

Ecosystem Stability and Resilience

Complex food webs tend to be more stable and resilient than simple ones. If a single prey species declines in a simple food chain, its predator might face starvation. In a complex food web, however, a predator often has multiple prey options. This redundancy provides a buffer against disturbances, allowing the ecosystem to absorb shocks and recover more effectively. Biodiversity, the variety of life in an ecosystem, directly contributes to this complexity and stability.

The Ripple Effect: Impact of Species Loss

The interconnected nature of food webs means that the loss of even a single species can have far-reaching, unpredictable consequences. The removal of a keystone species, one that has a disproportionately large effect on its environment relative to its abundance, can cause an entire food web to unravel. For instance, if a top predator is removed, its prey population might explode, leading to overgrazing of plants, which then impacts herbivores and other organisms dependent on those plants. This is often referred to as a trophic cascade.

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification

Food webs also play a crucial role in understanding how pollutants move through an ecosystem. Certain toxins, such as pesticides or heavy metals, can accumulate in the tissues of organisms. This process is called bioaccumulation. As these contaminated organisms are consumed by others, the concentration of the toxin increases at each successive trophic level, a phenomenon known as biomagnification. Top predators often accumulate the highest levels of these harmful substances, highlighting the interconnected health of all organisms within the web.

Human Impact on Food Webs

Human activities profoundly influence food webs globally. Habitat destruction, pollution, overfishing, hunting, and climate change all disrupt natural feeding relationships. Introducing invasive species can also wreak havoc, as these newcomers often lack natural predators and outcompete native species, altering the delicate balance of the web. Recognizing these impacts is the first step towards developing sustainable practices that protect and restore the health of our planet’s ecosystems.

Conclusion: The Interwoven Fabric of Life

From the smallest microbe to the largest whale, every organism is a thread in the grand tapestry of a food web. These intricate networks are not just about who eats whom; they are about the flow of energy, the cycling of nutrients, the stability of ecosystems, and ultimately, the survival of life itself. Understanding food webs allows us to appreciate the profound interconnectedness of nature and recognize our own place within this magnificent, dynamic system. By safeguarding the health and diversity of these webs, we ensure the resilience of our planet and the well-being of all its inhabitants.