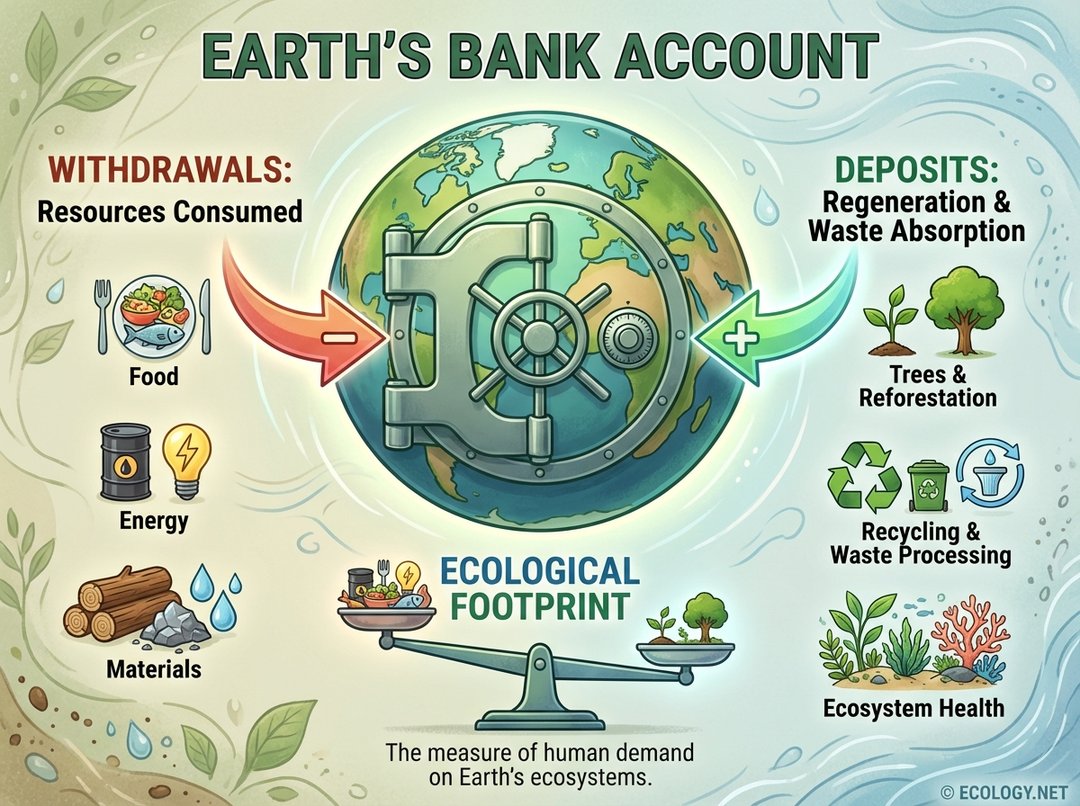

Imagine our planet as a vast, living bank account. It has a finite amount of capital in the form of natural resources, and it also has an income stream: its capacity to regenerate those resources and absorb our waste. Just like a personal bank account, if withdrawals consistently exceed deposits, the account balance dwindles, eventually leading to bankruptcy. This powerful analogy lies at the heart of understanding the Ecological Footprint, a crucial metric that helps us measure humanity’s demand on nature.

What is an Ecological Footprint? The Earth’s Bank Account Analogy

At its core, an Ecological Footprint quantifies the amount of biologically productive land and sea area required to produce all the resources an individual, a city, a country, or humanity consumes, and to absorb the waste generated. It is a comprehensive accounting tool that translates our consumption patterns into a universal unit: global hectares (gha).

Think of it as a balance sheet for our planet. On one side, we have biocapacity, which represents the Earth’s ability to regenerate resources and absorb waste. This includes forests that grow timber and absorb carbon dioxide, fertile land that produces food, and oceans that provide fish. On the other side, we have humanity’s demand, our Ecological Footprint, which encompasses everything from the food we eat and the clothes we wear to the energy that powers our homes and transportation.

When our withdrawals (consumption) exceed the Earth’s deposits (regeneration), we are essentially drawing down our planet’s natural capital. This is an unsustainable path, akin to spending more than we earn year after year.

Why Does Your Footprint Matter?

Understanding your Ecological Footprint is more than just an academic exercise. It is a direct measure of our impact on the planet’s life-support systems. A large footprint indicates a high demand on natural resources and a significant contribution to environmental degradation, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource scarcity. Conversely, a smaller footprint signifies a more sustainable lifestyle, living within the Earth’s means.

Components of Your Ecological Footprint: What’s in Your Shopping Cart?

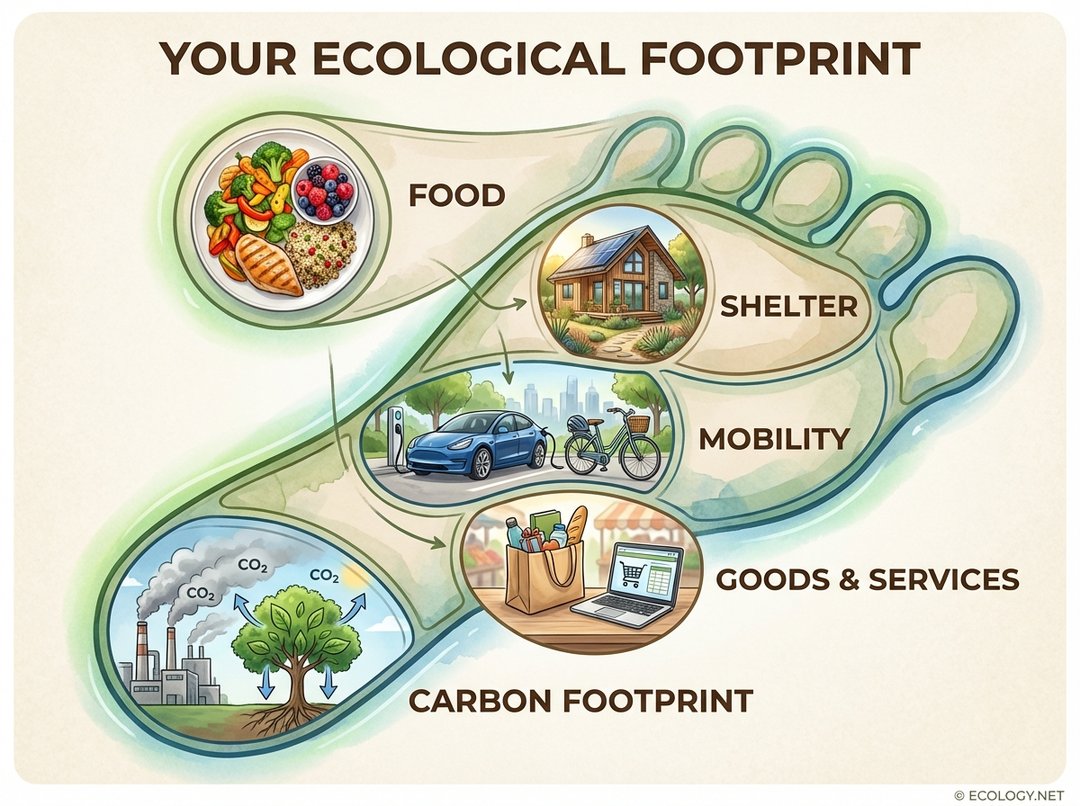

The beauty of the Ecological Footprint concept is its ability to break down our overall impact into tangible categories. It is not just about carbon emissions, though that is a significant part. It is about the full spectrum of our daily lives.

Food

The food we choose to eat has a profound impact. This component accounts for the land and resources used to grow, harvest, process, package, and transport our food. Consider the difference between a locally grown, seasonal vegetable and an imported, out-of-season fruit that traveled thousands of miles. Meat, particularly beef, generally has a much larger footprint than plant-based foods due to the land required for grazing, feed production, and methane emissions from livestock.

- Examples:

- Land for crops (grains, vegetables, fruits)

- Pasture for livestock (cattle, sheep)

- Fishing grounds for seafood

- Energy for processing, packaging, and transportation

Shelter

The homes we live in and how we power them contribute significantly to our footprint. This includes the land occupied by our dwellings, the materials used in construction, and especially the energy consumed for heating, cooling, lighting, and appliances. A large, inefficient home powered by fossil fuels will have a much larger footprint than a smaller, energy-efficient dwelling powered by renewable sources.

- Examples:

- Land for housing and infrastructure

- Materials for construction (wood, concrete, steel)

- Energy for heating, cooling, and electricity (coal, natural gas, solar)

Mobility

How we get around, whether for daily commutes or international travel, is another major factor. This component measures the land and resources required for transportation infrastructure (roads, airports) and the energy consumed by vehicles. Flying, driving single-occupancy vehicles, and long-distance shipping all contribute substantially to this part of the footprint.

- Examples:

- Fuel for cars, buses, trains, airplanes

- Infrastructure for roads, railways, airports

- Manufacturing of vehicles

Goods & Services

Virtually everything we buy, from clothing and electronics to furniture and household items, has an Ecological Footprint. This category accounts for the resources extracted, processed, manufactured, transported, and disposed of for all the products and services we consume. Fast fashion, disposable items, and excessive consumption all inflate this component.

- Examples:

- Raw materials for products (minerals, timber, cotton)

- Energy for manufacturing processes

- Waste disposal and recycling infrastructure

- Services like healthcare, education, and entertainment (and their associated resource use)

Carbon Footprint

While often discussed separately, the carbon footprint is a critical subset of the overall Ecological Footprint. It specifically measures the amount of biologically productive land and sea area required to absorb the carbon dioxide emissions generated by human activities. This includes emissions from burning fossil fuels for energy, industrial processes, and deforestation. It is often the largest component for many individuals and nations.

- Examples:

- Emissions from power generation (electricity)

- Emissions from transportation (cars, planes)

- Emissions from industrial production

- Emissions from heating and cooling buildings

The Global Picture: Ecological Overshoot Day

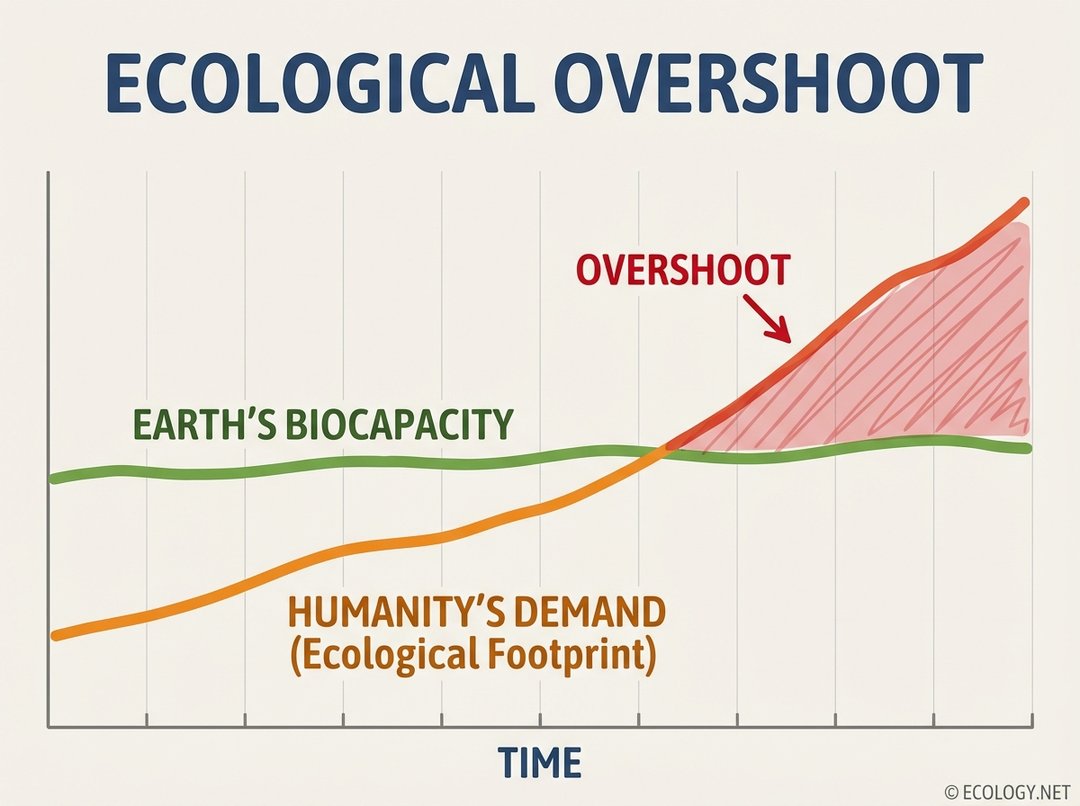

When we aggregate all individual and national footprints, we arrive at humanity’s total Ecological Footprint. For decades, this global footprint has exceeded the Earth’s biocapacity. This critical point is known as ecological overshoot.

To make this concept more tangible, the Global Footprint Network calculates Earth Overshoot Day each year. This is the date when humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year. In essence, it is the day we have used up our annual planetary budget and begin operating on ecological debt, drawing down natural capital from future generations. In recent years, Earth Overshoot Day has fallen earlier and earlier, signaling an accelerating rate of resource depletion.

Living in overshoot means we are depleting fish stocks faster than they can reproduce, harvesting forests more quickly than they can regrow, emitting more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than ecosystems can absorb, and drawing down freshwater reserves faster than they can be replenished. This is not merely an environmental problem; it is an economic and social challenge that threatens global stability and well-being.

Calculating Your Footprint: A Personal Check-up

Many online calculators allow individuals to estimate their personal Ecological Footprint. These tools typically ask a series of questions about lifestyle choices, such as diet, transportation habits, household energy use, and consumption patterns. While these calculators provide estimates, they are invaluable for raising awareness and highlighting areas where personal changes can make a difference. They serve as a mirror, reflecting the impact of our choices on the planet.

Reducing Your Ecological Footprint: Steps Towards a Sustainable Future

The good news is that reducing our Ecological Footprint is entirely within our grasp, both individually and collectively. It requires conscious choices and a shift towards more sustainable practices.

Dietary Choices

- Embrace plant-rich diets: Reducing meat and dairy consumption, especially red meat, can significantly lower your food footprint.

- Choose local and seasonal foods: Support local farmers and reduce the energy associated with long-distance transportation.

- Minimize food waste: Plan meals, store food properly, and compost scraps.

Energy Efficiency at Home

- Improve insulation: Reduce energy needed for heating and cooling.

- Switch to renewable energy: Consider solar panels or choose an energy provider that sources from renewables.

- Unplug electronics: Reduce “vampire” energy drain.

- Use energy-efficient appliances: Look for ENERGY STAR ratings.

Sustainable Transportation

- Walk, cycle, or use public transport: Reduce reliance on personal vehicles.

- Carpool: Share rides to reduce individual vehicle use.

- Choose efficient vehicles: Opt for electric or hybrid cars if driving is necessary.

- Reduce air travel: Consider alternatives for shorter distances or combine trips.

Mindful Consumption

- Buy less, choose well: Invest in durable, high-quality items that last.

- Reduce, reuse, recycle: Prioritize reducing consumption and reusing items before recycling.

- Support ethical and sustainable brands: Choose companies committed to environmental responsibility.

- Repair instead of replacing: Extend the life of your belongings.

Advocacy and Community Action

- Engage in local initiatives: Participate in community gardens, clean-up drives, or advocacy groups.

- Vote for sustainable policies: Support leaders who prioritize environmental protection and resource management.

- Educate others: Share knowledge about the Ecological Footprint and sustainable living.

Beyond the Individual: Systemic Change and Policy

While individual actions are vital, addressing the global ecological overshoot also requires systemic change. Governments, industries, and international organizations play a crucial role in shaping the context within which individuals make choices. Policies that promote renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, circular economy principles, and robust conservation efforts are essential to shift humanity’s trajectory towards sustainability. Investing in green infrastructure, incentivizing eco-friendly businesses, and regulating resource extraction are all critical components of a comprehensive solution.

Conclusion: Stepping Lightly on Our Planet

The Ecological Footprint provides a powerful, science-based framework for understanding our relationship with the natural world. It moves beyond abstract environmental concerns to offer a clear, quantifiable measure of our impact. By recognizing that we are currently overdrawing from Earth’s bank account, we are empowered to make more informed decisions. Every choice, from the food on our plate to the energy that powers our lives, contributes to our collective footprint. By striving to reduce our individual and collective footprints, we can work towards a future where humanity lives within the regenerative capacity of our remarkable planet, ensuring a healthy and prosperous existence for all.