The Art of Sharing: Unpacking Dietary Partitioning in Nature

Imagine a bustling restaurant where everyone wants the same dish. Chaos, right? Now, picture that same restaurant, but each group of diners specializes in a different part of the menu, or even eats at different times. Suddenly, there is harmony, less pushing, and everyone gets fed. This simple analogy mirrors one of nature’s most elegant solutions to the universal challenge of survival: dietary partitioning.

In the intricate tapestry of ecosystems, countless species often vie for the same limited resources. Without clever strategies, this competition could lead to the extinction of less dominant species. Dietary partitioning is a fundamental ecological principle that allows diverse species to coexist by dividing up available food resources, thereby minimizing direct competition and fostering biodiversity.

What is Dietary Partitioning?

At its core, dietary partitioning is the process by which coexisting species reduce interspecific competition by consuming different types of food, foraging in different places, or feeding at different times. It is a sophisticated form of resource partitioning specifically focused on diet. Instead of fighting over every morsel, species find their own niche, their own specialized way to tap into the shared bounty of an ecosystem.

This strategy is crucial for maintaining the rich biodiversity we observe in nature. Without it, competitive exclusion would likely lead to a much simpler, less vibrant array of life forms. It is a testament to evolution’s ingenuity, constantly shaping species to find unique ways to thrive alongside their neighbors.

Why is it Important? The Dance of Coexistence

The importance of dietary partitioning extends far beyond simply avoiding a squabble over food. It is a cornerstone of ecological stability and biodiversity. When species partition resources, several vital outcomes emerge:

- Reduced Competition: The most immediate benefit is a decrease in direct competition for food, allowing more species to coexist in the same habitat.

- Increased Biodiversity: By enabling more species to share an environment, dietary partitioning directly contributes to higher species richness and ecological complexity.

- Efficient Resource Utilization: Different species often exploit different aspects of a resource, leading to a more thorough and efficient use of available food within an ecosystem.

- Ecosystem Stability: A diverse ecosystem with many coexisting species is generally more resilient to disturbances and environmental changes.

Mechanisms of Dietary Partitioning

Species employ a variety of ingenious methods to partition their diets. These mechanisms can often overlap and interact, creating highly specialized ecological niches.

- Resource Type Partitioning:

- This is perhaps the most straightforward mechanism, where species consume entirely different kinds of food.

- For example, in a forest, one bird species might specialize in eating insects, another on seeds, and a third on nectar.

- Even within a category, there can be further partitioning, such as different insectivorous birds preferring different insect orders or life stages.

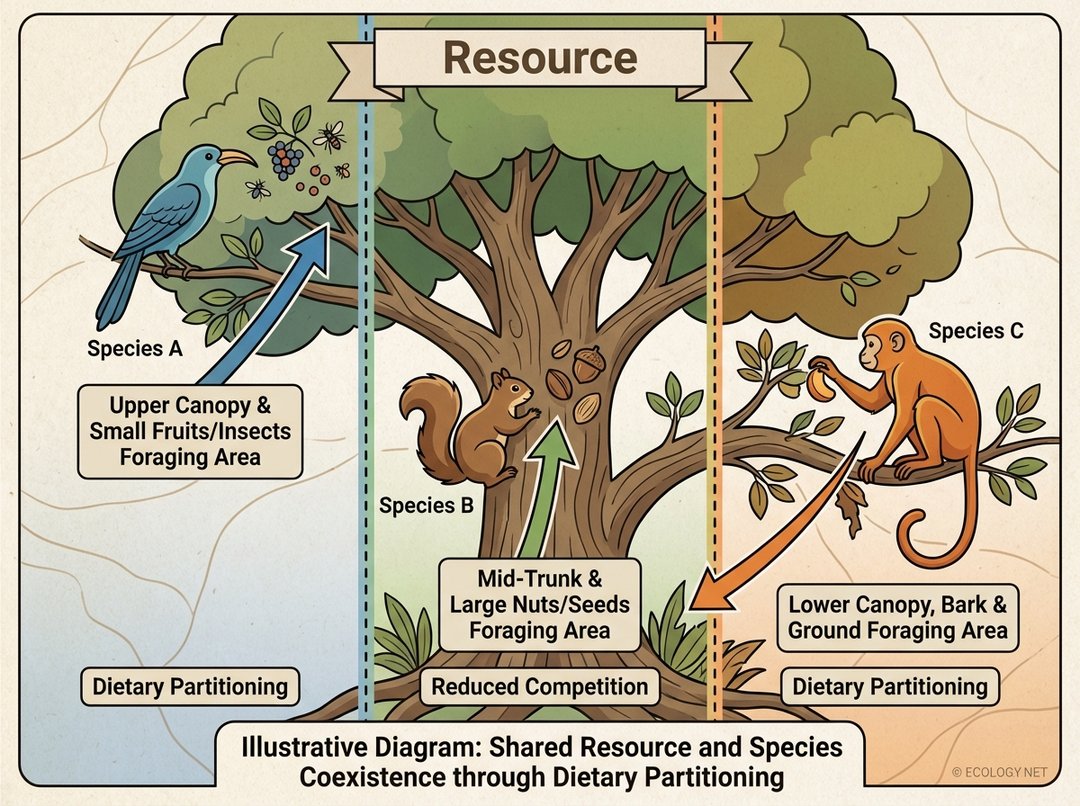

- Spatial Partitioning:

- Species may forage in different physical locations within the same habitat.

- This could mean feeding at different heights in a tree, different depths in a body of water, or different microhabitats on the forest floor.

- A classic example involves birds foraging in different parts of the same tree.

- Temporal Partitioning:

- Species might exploit the same food resources but at different times.

- This can involve feeding during different times of the day (e.g., nocturnal versus diurnal predators), or during different seasons.

- For instance, some insect species might be active and feeding in spring, while others emerge and feed in summer.

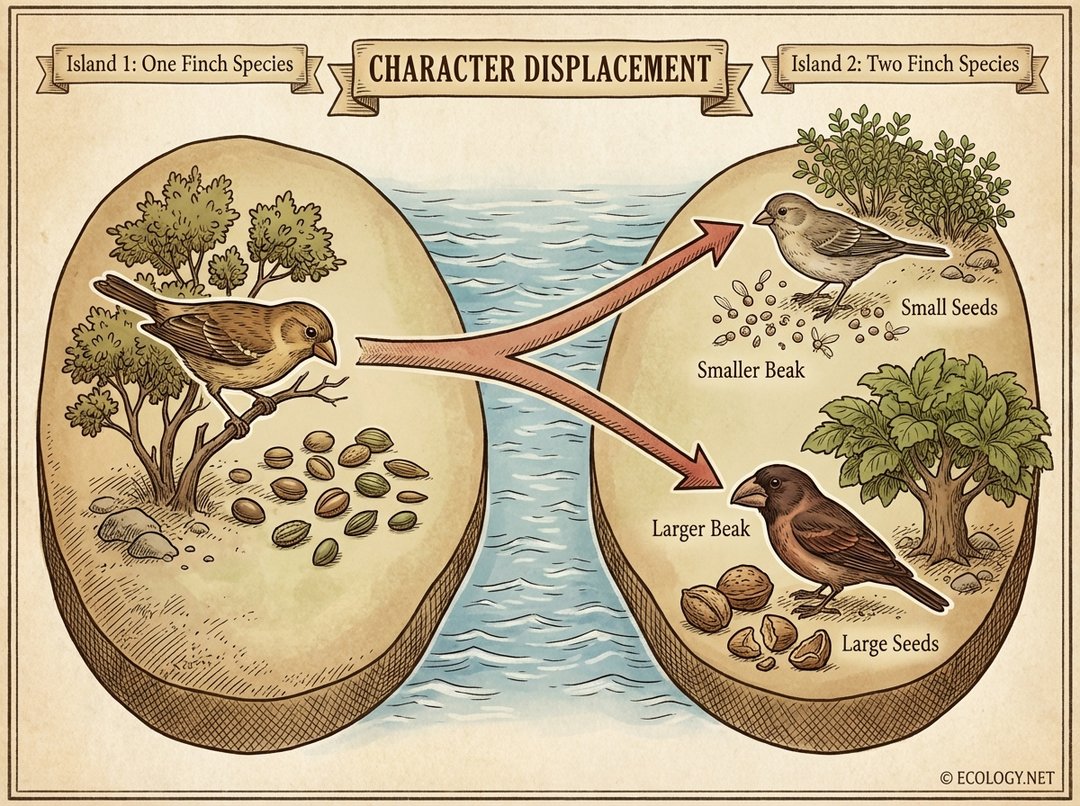

- Size Partitioning:

- Even if species eat the same general type of food, they might specialize in different sizes of that food.

- Consider finches with different beak sizes, where one species might crack small seeds and another large, tough seeds.

- Predators might also specialize in different sizes of prey, even if they hunt the same prey species.

A Simple Illustration: Warblers in the Forest

One of the most famous and easily understood examples of dietary partitioning comes from the warblers of North American forests. Several species of warblers, all insectivorous, can coexist in the same trees without driving each other to extinction. How do they manage this?

They employ spatial partitioning. Each warbler species has evolved to forage predominantly in a specific part of the tree canopy:

- The Cape May Warbler often feeds on the outer tips of the upper branches.

- The Black-throated Green Warbler tends to forage in the middle branches.

- The Yellow-rumped Warbler might be found lower down, often near the trunk or on the undersides of branches.

By specializing in these different zones, they effectively divide the insect buffet available in the tree. While their diets might overlap somewhat, the primary foraging locations minimize direct encounters and competition for the same specific insects at the same time. This elegant solution allows multiple species to thrive within the same resource base.

Beyond Simple Sharing: The Evolutionary Impact

Dietary partitioning is not just a static arrangement. It is a dynamic process that can drive evolutionary change, shaping the very traits of species over generations.

Character Displacement

One of the most fascinating evolutionary consequences of competition and partitioning is character displacement. This occurs when two similar species, living in the same area, evolve to become more different from each other in traits that relate to resource use, such as beak size, body size, or foraging behavior. The pressure of competition pushes them to specialize further, reducing overlap.

A prime example is found in Darwin’s Finches on the Galapagos Islands. On islands where only one finch species exists, it often has a medium-sized beak, capable of eating a wide range of seeds. However, on islands where two or more finch species coexist, their beak sizes tend to diverge significantly. One species might evolve a smaller beak to specialize in small seeds, while another develops a larger, stronger beak for cracking tough, large seeds. This evolutionary divergence reduces competition and allows both species to persist.

Niche Specialization

Over long evolutionary timescales, dietary partitioning can lead to extreme niche specialization. Species become highly adapted to a very specific diet or foraging method. While this makes them incredibly efficient at exploiting their particular resource, it can also make them vulnerable if that resource diminishes or disappears. Think of a koala, perfectly adapted to a eucalyptus diet, but unable to switch to other leaves if eucalyptus forests are destroyed.

Real-World Examples of Dietary Partitioning

The principles of dietary partitioning are observable across virtually all ecosystems and taxonomic groups:

- African Savanna Herbivores: Zebras, wildebeest, and gazelles graze on the same grasslands but partition their diets. Zebras are “bulk grazers” eating tall, coarse grasses. Wildebeest follow, consuming the shorter, more nutritious leaves and stems left behind. Gazelles then pick at the finest, shortest grasses and forbs. This sequential grazing allows multiple species to utilize the same patch of savanna.

- Marine Ecosystems: Different species of fish in a coral reef might specialize in eating different types of algae, small invertebrates, or detritus. Seabirds, while often feeding on fish, might partition by hunting at different depths, targeting different fish species, or foraging at different distances from the shore.

- Insect Communities: In a single tree, various insect species might feed on different parts: some on leaves, others on bark, some on roots, and still others on the sap or flowers. Even leaf-eating insects might specialize in young leaves versus mature leaves, or different parts of a single leaf.

- Predators: In a forest, a hawk might hunt during the day, preying on small mammals and birds, while an owl hunts at night, targeting similar prey. This temporal partitioning reduces direct competition between these two apex predators.

The Broader Ecological Implications

Understanding dietary partitioning is not merely an academic exercise. It has profound implications for conservation and ecosystem management:

- Biodiversity Maintenance: Recognizing how species partition resources helps us understand the conditions necessary for maintaining high biodiversity. Loss of habitat or key resources can disrupt these delicate partitioning strategies, leading to increased competition and potential species decline.

- Ecosystem Stability: Ecosystems with robust dietary partitioning among their species tend to be more stable and resilient. If one food source temporarily declines, other species are not necessarily impacted as severely, and the overall ecosystem function can continue.

- Conservation Relevance: When designing conservation strategies, it is crucial to consider the dietary needs and partitioning strategies of endangered species. Protecting not just a species, but also its specific food resources and foraging habitats, is paramount for its survival.

- Invasive Species: Invasive species often succeed by directly competing with native species for resources, sometimes disrupting established dietary partitioning patterns and leading to declines in native populations.

Conclusion

Dietary partitioning is a fundamental ecological principle, a testament to nature’s boundless capacity for innovation. It is the elegant solution that allows a multitude of life forms to share the planet’s finite resources, transforming potential conflict into a complex dance of coexistence. From warblers in a forest canopy to finches on isolated islands, and the diverse grazers of the savanna, the art of sharing food resources underpins the very structure and stability of ecosystems worldwide. By appreciating this intricate ecological strategy, we gain a deeper understanding of the natural world and the vital importance of preserving the delicate balance that allows life to flourish in all its magnificent diversity.