In the intricate dance of life, where every organism strives to survive and reproduce, a fundamental force shapes communities and drives evolution: competition. Far from being a simple struggle, ecological competition is a complex interaction that dictates who eats what, where they live, and ultimately, who thrives. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for comprehending the distribution of species, the structure of ecosystems, and even the future of biodiversity.

At its core, competition occurs when two or more organisms require the same limited resource. This resource could be anything vital for survival: food, water, light, space, mates, or even nesting sites. When demand for these resources exceeds supply, organisms inevitably come into conflict, directly or indirectly, with profound consequences for all involved.

Unpacking the Types of Ecological Competition

Ecologists categorize competition in several ways, helping us to better understand its mechanisms and impacts. The primary distinctions revolve around how organisms interact and whether they belong to the same species.

Direct vs. Indirect Competition

The first way to classify competition considers the nature of the interaction:

- Direct Competition (Interference Competition): This occurs when individuals physically interact and prevent others from accessing resources. It is often aggressive and observable.

- Indirect Competition (Exploitation Competition): This happens when organisms consume or deplete a shared resource, making less of it available for others, without direct confrontation.

- Example: A large herd of deer grazing in a meadow, consuming so much grass that the remaining grass becomes sparse and insufficient for other herbivores.

- Example: Different species of fish feeding on the same plankton population, where the consumption by one species reduces the food available for another.

Intraspecific vs. Interspecific Competition

The second classification focuses on the relationship between the competing organisms:

- Intraspecific Competition: This occurs among individuals of the same species. It is a powerful force driving natural selection, as individuals within a species compete for resources, mates, and territory.

- Example: Two male deer locking antlers during the rutting season, competing for access to females.

- Example: Saplings of the same tree species growing close together, competing for sunlight, water, and soil nutrients, often leading to the suppression or death of weaker individuals.

- Interspecific Competition: This occurs between individuals of different species. It plays a crucial role in shaping community structure, determining which species can coexist and where they can live.

- Example: A European starling aggressively occupying a birdhouse entrance, preventing a smaller, native bluebird from nesting there.

- Example: Cheetahs and lions hunting the same prey species, such as gazelles, in the African savanna.

The Profound Outcomes of Ecological Competition

Competition is not merely an interaction; it leads to significant ecological outcomes that influence species distribution, population dynamics, and even evolutionary trajectories. Two of the most well-known outcomes are competitive exclusion and resource partitioning.

Competitive Exclusion Principle

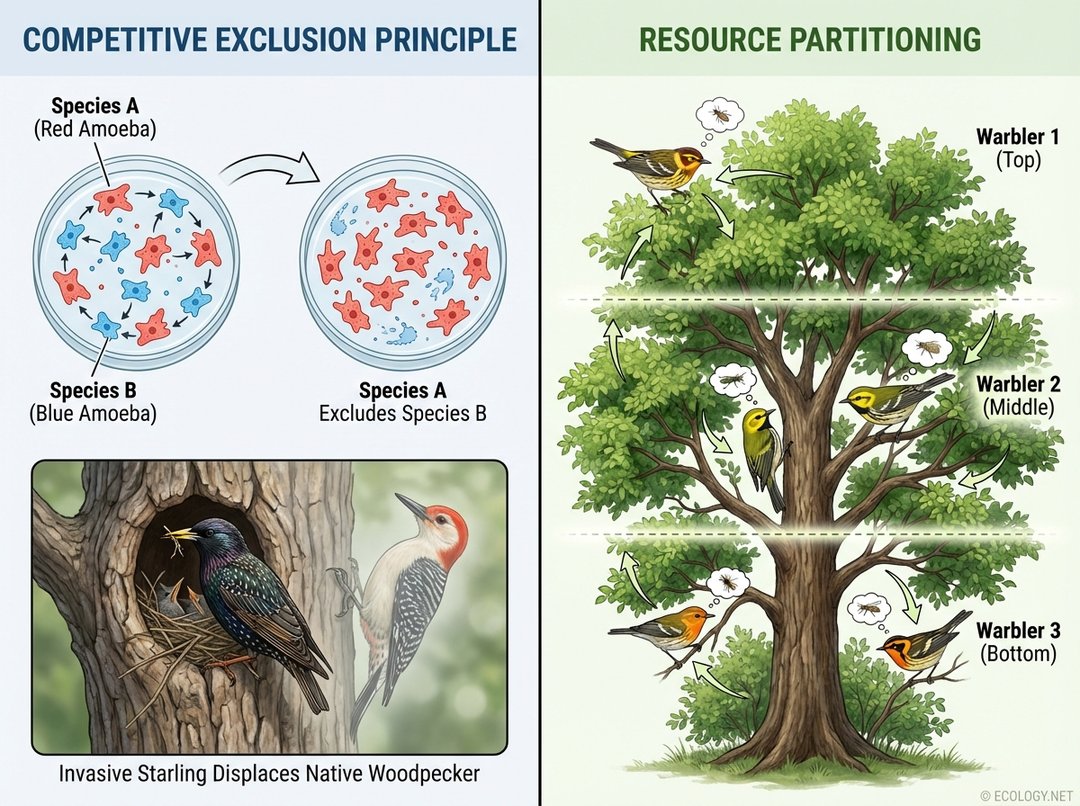

One of the most dramatic outcomes of interspecific competition is the Competitive Exclusion Principle, also known as Gause’s Law. This principle states that two species competing for the exact same limited resources cannot stably coexist. One species will inevitably outcompete the other, leading to the exclusion of the less competitive species.

The Competitive Exclusion Principle highlights that complete competitors cannot coexist. If two species have identical resource requirements, one will always win.

- Classic Experiment: Russian ecologist G.F. Gause demonstrated this with two species of Paramecium. When grown separately, both thrived. When grown together with limited resources, one species consistently outcompeted and eliminated the other.

- Real-world Example: The introduction of the European starling to North America led to the displacement of many native cavity-nesting birds, such as woodpeckers and bluebirds, from their nesting sites. Starlings are highly aggressive and adaptable, often outcompeting native species for limited tree cavities.

Resource Partitioning

While competitive exclusion can lead to the loss of species, it is not the only outcome. Often, species that initially compete intensely can evolve mechanisms to reduce competition, allowing them to coexist. This process is known as resource partitioning.

Resource partitioning occurs when species divide up a shared resource, specializing in different aspects of it. This can involve using different parts of a habitat, feeding at different times of day, or consuming different types of food items.

- Example: Several species of warblers in a single deciduous tree. Instead of competing directly for all insects throughout the tree, different warbler species forage in distinct zones: one might feed primarily in the top canopy, another in the middle branches, and a third in the lower foliage. This specialization reduces direct competition and allows multiple species to coexist.

- Example: Different species of lizards on a Caribbean island. While they all eat insects, some may hunt on tree trunks, others on the ground, and still others in the canopy, effectively partitioning the insect resource by habitat.

The Niche: Fundamental vs. Realized

To fully grasp the impact of competition, we must understand the concept of an ecological niche. A niche is more than just a species’ habitat; it encompasses all the environmental conditions, resources, and interactions a species needs to survive and reproduce. It is essentially a species’ role or profession within an ecosystem.

Fundamental Niche

The fundamental niche represents the full range of environmental conditions and resources that a species could potentially use and occupy if there were no competition or other limiting factors (like predators or disease). It is the theoretical maximum space and resource utilization for a species.

- Example: A specific barnacle species might be physiologically capable of surviving and reproducing across a wide range of an intertidal zone, from high tide to low tide, if it were the only species present. This entire potential range is its fundamental niche.

Realized Niche

The realized niche, in contrast, is the actual set of environmental conditions and resources that a species occupies and uses in the presence of competition and other limiting factors. It is often a smaller, more restricted subset of the fundamental niche.

Competition is a primary force that shrinks a species’ fundamental niche into its realized niche. When a species faces competition from others, it may be forced to utilize only a portion of the resources or habitats it is physiologically capable of using.

- Example: Continuing with the barnacle example, in reality, the barnacle species might only be found in the lower part of the intertidal zone because a more competitive barnacle species occupies the upper zone, outcompeting it for space and resources there. The lower zone is its realized niche, restricted by interspecific competition.

The distinction between fundamental and realized niches is a powerful tool for ecologists to understand how species interactions, particularly competition, shape the distribution and abundance of organisms in nature.

Competition’s Broader Ecological Significance

The pervasive nature of competition means its influence extends far beyond individual interactions, shaping entire ecosystems and driving evolutionary change.

- Evolutionary Driver: Competition acts as a strong selective pressure. Individuals that are better competitors for limited resources are more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their traits. This can lead to evolutionary adaptations, such as stronger defenses, more efficient foraging strategies, or specialized resource use, which in turn can lead to resource partitioning.

- Biodiversity Maintenance: While competitive exclusion can reduce local diversity, resource partitioning allows for the coexistence of many species, contributing to overall biodiversity. The intricate ways species divide resources create complex and stable communities.

- Community Structure: Competition is a major determinant of which species can live together in a particular habitat and in what numbers. It influences food webs, population sizes, and the overall health of an ecosystem.

- Conservation and Management: Understanding competitive dynamics is critical for conservation efforts. When invasive species are introduced, they often outcompete native species, leading to declines or extinctions. Conservationists must consider competitive interactions when managing endangered species or restoring habitats.

Conclusion

Ecological competition is a relentless, yet vital, force in the natural world. From the microscopic battlegrounds of bacteria to the vast savannas where predators vie for prey, competition shapes every aspect of life. It drives evolution, dictates species distribution, and structures the complex tapestry of ecosystems.

By dissecting its various forms, understanding its profound outcomes like competitive exclusion and resource partitioning, and appreciating its role in defining ecological niches, we gain a deeper appreciation for the delicate balance and constant flux that characterize our planet’s biodiversity. Recognizing competition’s power is not just an academic exercise; it is essential for effective conservation and for safeguarding the intricate web of life that sustains us all.