Life on Earth is not a collection of isolated species, but rather an intricate web of interactions. From the smallest microbe to the largest whale, organisms are constantly influencing each other, shaping their forms, behaviors, and very destinies. This grand, ongoing evolutionary dance, where two or more species reciprocally affect each other’s evolution, is known as coevolution.

What is Coevolution? The Evolutionary Dance of Species

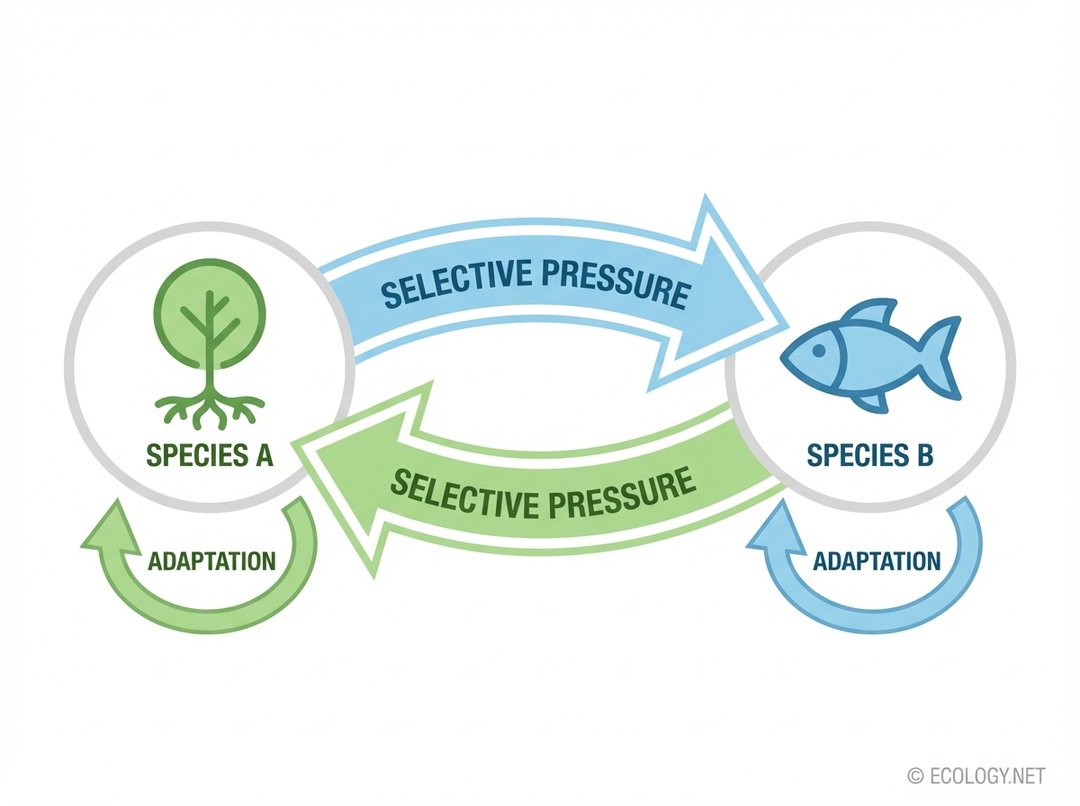

At its core, coevolution describes a process where the evolutionary changes in one species act as a selective pressure on another species, leading to adaptations in the second species. These adaptations, in turn, create new selective pressures on the first species, driving further evolutionary change. It is a continuous, reciprocal feedback loop, a biological conversation spanning millennia.

Imagine two species locked in a perpetual interaction. As one species evolves a new trait, perhaps a stronger defense mechanism, the other species must adapt to overcome this defense, or face extinction. This adaptation then prompts a counter-adaptation in the first species, and so the cycle continues. This dynamic interplay is what makes coevolution such a powerful force in shaping biodiversity.

The concept of coevolution highlights that species do not evolve in a vacuum. Their evolutionary trajectories are deeply intertwined with those of other species with whom they interact closely. These interactions can take many forms, leading to a fascinating array of coevolutionary outcomes.

Diverse Relationships: Types of Coevolution

Coevolutionary relationships are as varied as life itself, often categorized by the nature of the interaction between the species involved. Understanding these categories helps us appreciate the complexity and beauty of the natural world.

Mutualism: A Partnership for Survival

Mutualism is a coevolutionary relationship where both interacting species benefit from the association. These partnerships can range from facultative, where species can survive independently but do better together, to obligate, where one or both species cannot survive without the other.

- Pollination Syndromes: Perhaps the most famous examples of mutualistic coevolution involve flowering plants and their pollinators. Flowers evolve specific shapes, colors, scents, and nectar rewards to attract particular pollinators, while pollinators evolve specialized mouthparts, behaviors, and sensory abilities to efficiently extract nectar and pollen. Think of the long, slender beaks of hummingbirds perfectly adapted to reach nectar in tubular flowers, or the intricate mimicry of orchids that attract specific insect species.

- Seed Dispersal: Many plants rely on animals to disperse their seeds. Fruits evolve to be attractive and nutritious to animals, which then consume the fruit and excrete the seeds, often far from the parent plant, aiding in colonization. The tough seeds of many berries, for instance, are designed to pass through a bird’s digestive system unharmed.

- Mycorrhizal Fungi and Plants: Below ground, a vast network of mutualistic coevolution exists. Mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, extending the plant’s root system and enhancing its ability to absorb water and nutrients, while the plant provides the fungi with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis.

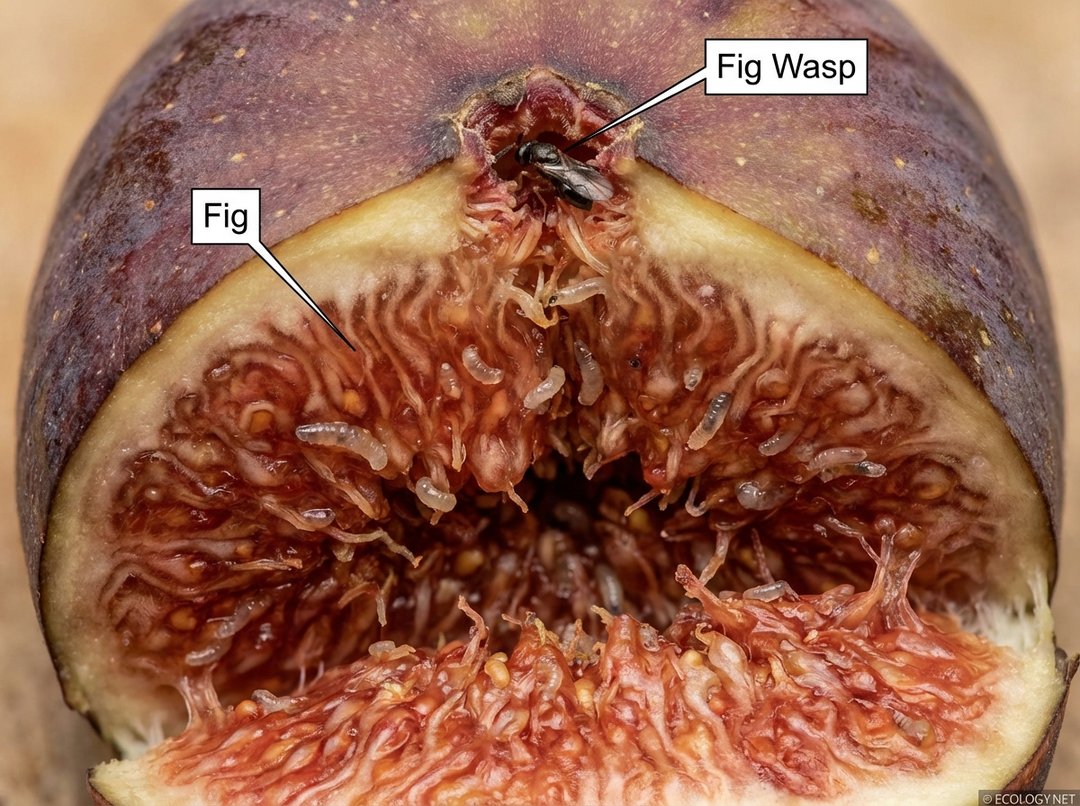

One of the most remarkable examples of obligate mutualism is the relationship between fig trees and fig wasps. Each species of fig tree is pollinated by a specific species of fig wasp, and these wasps can only reproduce inside the figs of their host tree. The fig provides a safe nursery for the wasp larvae, and in return, the female wasp pollinates the fig flowers as she lays her eggs. Neither can complete its life cycle without the other, a testament to millions of years of coevolutionary refinement.

Antagonism: The Evolutionary Arms Race

In antagonistic coevolution, one species benefits at the expense of the other. This dynamic often leads to a continuous escalation of adaptations and counter-adaptations, frequently referred to as an “evolutionary arms race.”

- Predator-Prey Relationships: Predators evolve more efficient hunting strategies, such as speed, camouflage, or enhanced senses, while prey species evolve better defenses, like increased vigilance, faster escape mechanisms, or improved camouflage. The constant pressure from predators drives the evolution of more evasive prey, which in turn drives the evolution of more effective predators.

- Host-Parasite Interactions: Parasites evolve to better exploit their hosts, often developing ways to evade the host’s immune system or manipulate its behavior. Hosts, in response, evolve stronger immune defenses or resistance mechanisms. This ongoing battle is crucial for understanding disease dynamics and the evolution of immunity.

- Herbivore-Plant Interactions: Plants develop a vast array of defenses against herbivores, including physical barriers like thorns and tough leaves, and chemical defenses such as toxins, deterrents, or digestibility reducers. Herbivores, in turn, evolve mechanisms to overcome these defenses, such as specialized enzymes to detoxify plant compounds or behavioral adaptations to avoid harmful parts of the plant.

A classic example of an antagonistic arms race involves the rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa) and the common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis). The newt produces a potent neurotoxin, tetrodotoxin (TTX), making it deadly to most predators. However, populations of garter snakes have coevolved a remarkable resistance to this toxin, allowing them to prey on the newts. This has led to a coevolutionary escalation, with newts evolving even higher levels of toxicity in areas where resistant snakes are present, and snakes evolving even greater resistance. It is a deadly dance where neither species can afford to fall behind.

Competition: The Struggle for Resources

While less direct than mutualism or antagonism, competition can also drive coevolutionary changes. When two species compete for the same limited resources, such as food, light, or space, they may evolve traits that reduce this competition. This can lead to character displacement, where competing species evolve to use different resources or occupy different niches, thereby minimizing direct conflict.

Beyond the Pair: Complex Coevolutionary Dynamics

While often illustrated with two species, coevolution can involve multiple species in complex webs of interaction. This leads to more nuanced and widespread evolutionary outcomes.

The Red Queen Hypothesis: Running to Stay in Place

The concept of the evolutionary arms race is often encapsulated by the Red Queen Hypothesis, inspired by Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking-Glass.” In the story, the Red Queen tells Alice, “It takes all the running you can do, just to stay in the same place.” In coevolutionary terms, this means that species must constantly evolve and adapt simply to maintain their current fitness relative to the species with which they interact. For instance, a host species must continually evolve new defenses against its parasites, not to gain an advantage, but merely to avoid being overwhelmed by the parasites’ own evolving virulence.

Diffuse Coevolution: A Web of Interactions

Many species interact with a multitude of other species. Diffuse coevolution occurs when a group of species coevolves with another group of species, rather than just a single pair. For example, a plant species might evolve a general defense mechanism that is effective against several different herbivore species, and these herbivores might, in turn, evolve a suite of adaptations to overcome these general defenses. This creates a broader, more complex coevolutionary landscape.

Geographic Mosaic of Coevolution: Hotspots and Coldspots

Coevolutionary interactions are not uniform across a species’ range. The strength and direction of coevolution can vary geographically, creating a “geographic mosaic of coevolution.” In some areas, an interaction might be strong, leading to rapid coevolutionary change (a “hotspot”), while in other areas, the interaction might be weak or absent, resulting in little to no coevolution (a “coldspot”). This mosaic pattern adds another layer of complexity to understanding how species evolve in response to each other.

Gene-for-Gene Coevolution: Precision at the Genetic Level

In some highly specific antagonistic relationships, particularly between plants and pathogens or hosts and parasites, coevolution can occur at the level of individual genes. This “gene-for-gene” coevolution describes a scenario where a specific gene in the host confers resistance to a pathogen, and a corresponding gene in the pathogen confers virulence, allowing it to overcome that resistance. This precise genetic interplay drives rapid evolutionary change and is a critical area of study in agriculture and disease resistance.

The Profound Significance of Coevolution

Coevolution is not merely an interesting biological phenomenon; it is a fundamental force that has profoundly shaped life on Earth and continues to do so. Its implications are far-reaching, touching upon biodiversity, ecosystem function, and even human endeavors.

- Driving Biodiversity: Coevolution is a major engine of speciation. As species adapt to each other, they can diverge into new forms, leading to an explosion of biodiversity. The intricate relationships between plants and insects, for example, have contributed immensely to the vast diversity of both groups.

- Shaping Ecosystems: Coevolutionary interactions are the glue that holds ecosystems together. They determine the structure of food webs, influence nutrient cycling, and regulate population dynamics. Without coevolution, ecosystems would look vastly different and function in radically altered ways.

- Relevance to Humanity:

- Agriculture: Understanding coevolution is vital for developing sustainable agricultural practices. It informs strategies for pest control, breeding disease-resistant crops, and managing beneficial insect populations.

- Medicine: The coevolutionary arms race between pathogens and their hosts is at the heart of infectious diseases. Insights from coevolution help us understand antibiotic resistance, develop new vaccines, and design more effective treatments for illnesses.

- Conservation: In a rapidly changing world, understanding coevolutionary dependencies is crucial for conservation efforts. Protecting one species often means protecting its coevolved partners, as the loss of one can trigger a cascade of extinctions.

Conclusion: A World Forged by Interaction

Coevolution reveals a world where no species is an island. Every organism is part of an ongoing, dynamic narrative, constantly adapting and responding to the evolutionary pressures exerted by its neighbors. From the delicate dance of a flower and its pollinator to the relentless arms race between predator and prey, coevolution is a testament to the interconnectedness of life.

This reciprocal evolutionary shaping has created the breathtaking diversity and complexity we observe in nature. It is a powerful reminder that understanding life requires looking beyond individual species and appreciating the profound and beautiful ways they have evolved together.