The Earth is a tapestry of life, woven with countless species interacting in intricate ecosystems. This incredible variety, known as biodiversity, is fundamental to the health of our planet and our own well-being. Yet, this precious biodiversity is under unprecedented threat. In the face of widespread environmental degradation, conservationists have developed a crucial concept to guide their efforts: the biodiversity hotspot.

Biodiversity hotspots are not merely beautiful places; they are critical battlegrounds for the future of life on Earth. These regions represent some of the most biologically rich and, simultaneously, most threatened terrestrial ecosystems. Understanding what they are, where they are, and why they matter is essential for anyone concerned about the natural world.

What Exactly Are Biodiversity Hotspots? Defining the Critical Zones

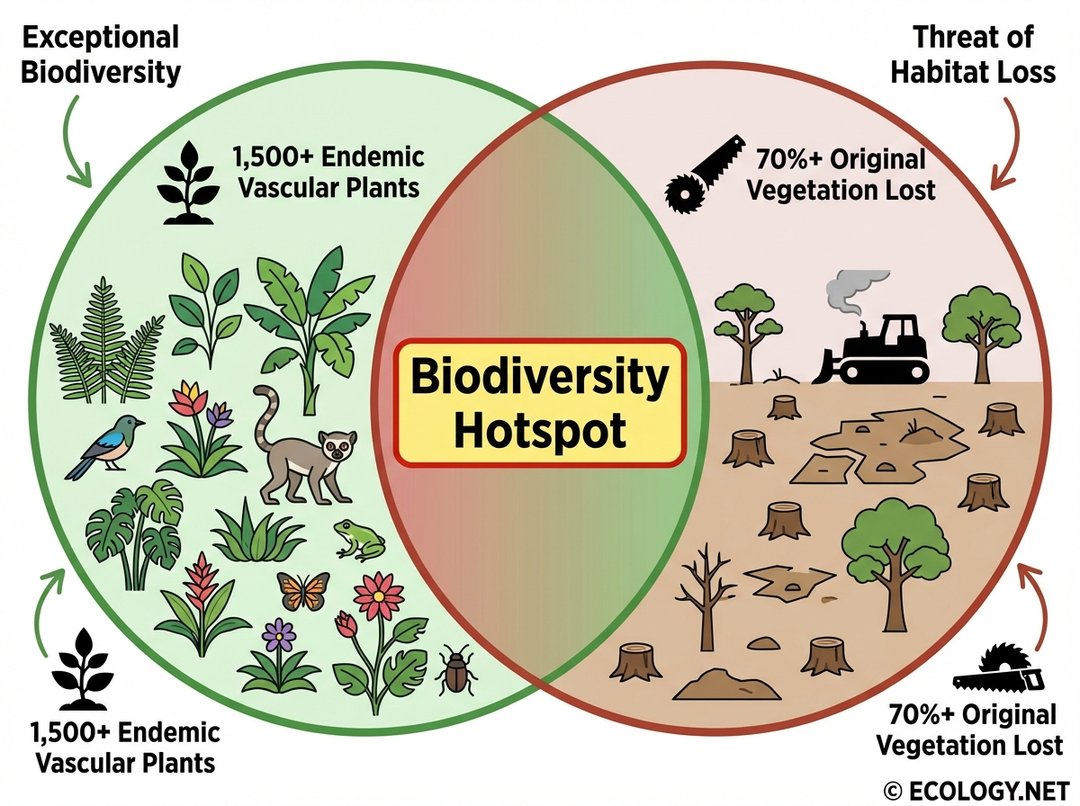

The term “biodiversity hotspot” was coined by Norman Myers in 1988 and later refined by Conservation International. It identifies areas that are both exceptionally rich in species and under severe threat of destruction. To qualify as a biodiversity hotspot, an area must meet two strict criteria:

- Exceptional Biodiversity (High Endemism): The region must contain at least 1,500 species of vascular plants as endemics. This means these plant species are found nowhere else on Earth. Endemism is a key indicator of unique evolutionary history and irreplaceable biodiversity.

- Significant Threat of Habitat Loss: The region must have lost at least 70% of its original natural vegetation. This criterion highlights the urgency of conservation, as these areas have already suffered massive habitat destruction and face ongoing threats.

These two conditions act as a powerful filter, identifying areas that are both biologically irreplaceable and critically endangered. It is a stark reminder that many of Earth’s most unique life forms are teetering on the brink.

Where Are These Hotspots? A Global Snapshot

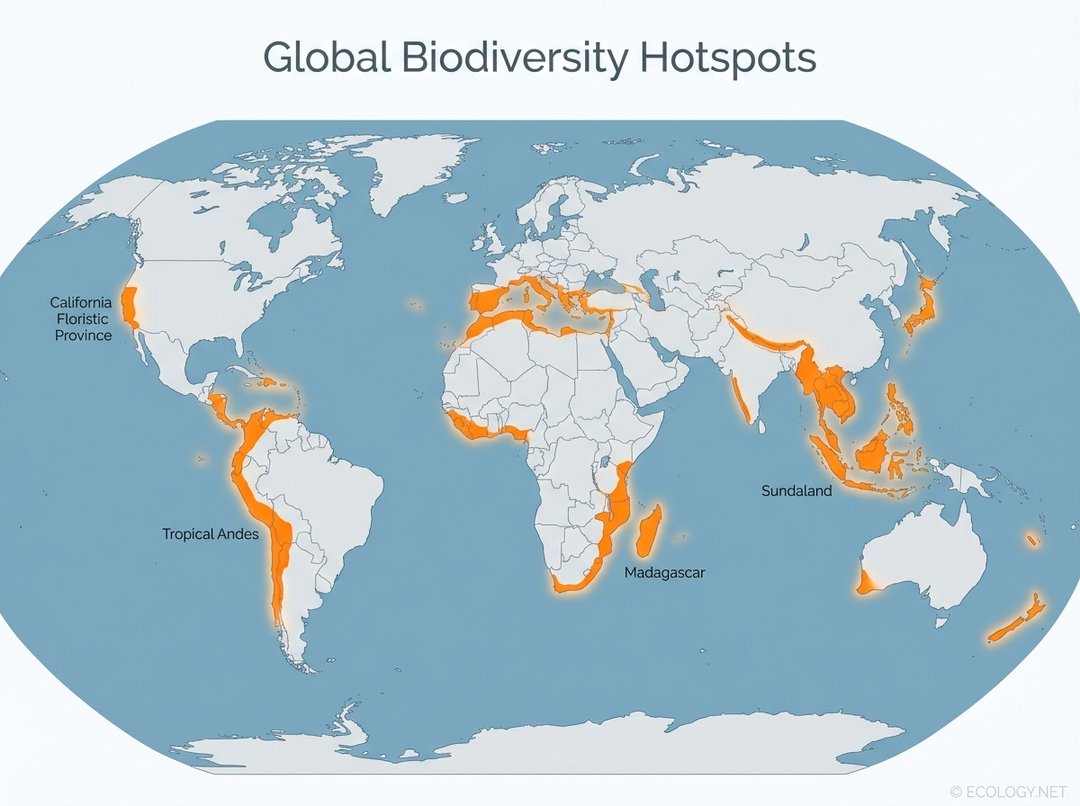

Currently, there are approximately 36 recognized biodiversity hotspots scattered across the globe. While they cover only about 2.5% of the Earth’s land surface, these relatively small areas harbor an astonishing proportion of the world’s biodiversity. They are home to over half of the world’s endemic plant species and nearly 43% of all endemic bird, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species.

These hotspots are not randomly distributed. Many are found in tropical and Mediterranean climate zones, often on islands or in mountainous regions, which tend to foster high rates of endemism due to geographical isolation. Examples include:

- Tropical Andes: Stretching along the western edge of South America, this region is the world’s most diverse hotspot, boasting an incredible array of plant and animal life, including many unique amphibians and birds.

- Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands: This island nation is a living laboratory of evolution, home to lemurs, unique baobab trees, and an extraordinary number of endemic reptiles and amphibians found nowhere else.

- Sundaland: Encompassing parts of Southeast Asia, including Borneo and Sumatra, this hotspot is famous for its rainforests, orangutans, and Sumatran rhinos, all facing severe threats from deforestation.

- California Floristic Province: Located in the western United States and Baja California, Mexico, this region is a global center of plant diversity, particularly known for its unique Mediterranean climate flora.

Why Focus on Hotspots? The Triage Approach to Conservation

Given the immense scale of environmental challenges and the finite nature of conservation resources, a strategic approach is crucial. The biodiversity hotspot concept provides a framework for prioritizing conservation efforts, much like a medical triage system in an emergency room.

By concentrating resources on these hotspots, conservationists aim to achieve the greatest possible impact in safeguarding global biodiversity. The logic is compelling:

- Maximizing Impact: Protecting a hotspot means protecting a disproportionately high number of unique species that would otherwise be lost forever.

- Preventing Extinction: The high level of threat in these areas means that without immediate intervention, many species face imminent extinction.

- Efficiency: Focusing efforts on a relatively small land area allows for more targeted and potentially more effective conservation strategies compared to spreading resources too thinly across vast, less threatened regions.

This approach acknowledges that not every area can be saved, but by focusing on the most critical, irreplaceable, and threatened regions, humanity can make significant strides in preserving the planet’s biological heritage.

The Criteria in Detail: A Closer Look at Endemism and Loss

The specific numbers in the hotspot criteria are not arbitrary; they reflect careful scientific consideration.

Understanding Endemic Vascular Plants

Why vascular plants? Vascular plants form the base of most terrestrial food webs. They are primary producers, providing food and habitat for countless other organisms. A high number of endemic vascular plants often indicates a high level of endemism across other taxonomic groups as well. The threshold of 1,500 species is significant because it represents a substantial and unique evolutionary heritage, suggesting a long history of isolation and diversification.

Gauging Habitat Loss

The 70% habitat loss threshold is a critical indicator of urgency. Losing 70% of original vegetation means that the remaining natural habitats are often fragmented, isolated, and highly vulnerable to further degradation. This level of loss severely impacts ecological processes, reduces population sizes of native species, and makes them more susceptible to disease, climate change, and genetic bottlenecks. “Original vegetation” refers to the natural state of the ecosystem before significant human alteration, providing a baseline against which current conditions are measured.

It is important to remember that these hotspots are dynamic. The threats they face are ongoing, and the status of their biodiversity can change. Continuous monitoring and adaptive management are crucial for effective conservation.

Examples of Biodiversity Hotspots and Their Unique Treasures

Delving into specific hotspots reveals the incredible diversity they protect:

- The Mediterranean Basin: This region, surrounding the Mediterranean Sea, is renowned for its unique flora, including many aromatic herbs and drought-adapted plants. It is also a crucial migratory route for birds. However, urban development, agriculture, and tourism pose significant threats.

- The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa: Despite its relatively small size, this hotspot has the highest non-tropical plant diversity in the world. It is home to the fynbos biome, a unique shrubland ecosystem with an astonishing number of endemic plant species, many of which are fire-adapted.

- Polynesia and Micronesia: These Pacific islands are a treasure trove of marine and terrestrial biodiversity, with many endemic birds, reptiles, and invertebrates. Rising sea levels, invasive species, and overfishing are major concerns for these fragile island ecosystems.

- The Atlantic Forest, Brazil: Once stretching along Brazil’s Atlantic coast, this forest has been reduced to fragments, yet it still harbors an incredible diversity of primates, birds, and amphibians, many of which are found nowhere else.

Each hotspot tells a story of unique evolution and pressing conservation needs, highlighting the global interconnectedness of life.

Challenges and Criticisms of the Hotspot Approach

While the biodiversity hotspot concept has been incredibly influential and successful in guiding conservation, it is not without its challenges and criticisms:

- Focus on Terrestrial Vascular Plants: The primary criterion for endemism is based on vascular plants. Critics argue this might overlook areas rich in other forms of life, such as marine species, fungi, or invertebrates, which also contribute significantly to biodiversity.

- Ignoring Other Important Areas: By focusing intensely on hotspots, there is a risk that other ecologically significant areas, such as vast wilderness areas with lower endemism but crucial ecological services, or “cold spots” that are less threatened but still important, might receive less attention and funding.

- Defining “Original Vegetation”: Establishing a precise baseline for “original vegetation” can be challenging, especially in regions with long histories of human impact. This can lead to debates about the exact extent of habitat loss.

- Dynamic Nature of Threats: The threats to biodiversity are constantly evolving. A region that is not a hotspot today could become one tomorrow, and vice versa. Continuous assessment is necessary.

Despite these valid points, the hotspot approach remains a powerful and widely accepted tool. Its effectiveness lies in its ability to galvanize action and direct resources where they can have the most immediate and profound impact on preventing extinctions.

Beyond Hotspots: Complementary Conservation Strategies

It is important to view biodiversity hotspots as one crucial component within a broader, multifaceted conservation strategy. Other approaches complement the hotspot model:

- High-Biodiversity Wilderness Areas (HBWAs): These are large, relatively intact natural areas that, while not meeting the 70% habitat loss criterion, are still incredibly rich in biodiversity and play vital roles in ecological processes. The Amazon rainforest and the Congo Basin are prime examples.

- Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs): This is a more granular approach, identifying sites of global importance for biodiversity based on a set of standardized criteria, including threatened species, restricted-range species, and ecological integrity.

- Ecoregions: These are large areas defined by their distinct natural communities and environmental conditions. Conservation efforts often focus on protecting representative examples of different ecoregions.

Ultimately, a holistic approach that integrates these various strategies is necessary to address the complex and interconnected challenges of global biodiversity conservation.

Conclusion: Guardians of Earth’s Living Heritage

Biodiversity hotspots are extraordinary places, cradles of unique life that have endured immense pressure. They serve as a powerful reminder of both the planet’s incredible biological richness and the urgent need for human stewardship. By understanding and supporting conservation efforts in these critical regions, individuals and organizations contribute directly to safeguarding a significant portion of Earth’s living heritage.

The fate of countless species, and indeed the health of our global ecosystems, hinges on the continued protection of these irreplaceable hotspots. Their preservation is not just an ecological imperative; it is an investment in the stability and beauty of our shared planet for generations to come.