The Earth is a vibrant tapestry of life, and much of its incredible diversity and resilience can be attributed to a remarkable, invisible blanket that envelops our planet: the atmosphere. Far from being just empty space above us, the atmosphere is a dynamic, multi-layered system that plays an indispensable role in sustaining all known life forms, regulating climate, and protecting the surface from the harshness of outer space. Understanding this vital component of our planet is key to appreciating the delicate balance of Earth’s ecosystems.

What is the Atmosphere? Earth’s Invisible Shield

At its most basic, the atmosphere is a vast envelope of gases surrounding Earth, held in place by gravity. It extends hundreds of kilometers into space, gradually thinning until it merges with the vacuum beyond. This gaseous shield is not uniform; it is a complex mixture of various elements and compounds, each contributing to its overall function. Without the atmosphere, Earth would be a barren, lifeless rock, much like the Moon, subject to extreme temperature swings and bombarded by harmful radiation.

Think of the atmosphere as Earth’s ultimate multi-purpose protector. It acts as a thermal blanket, trapping heat and preventing it from escaping too quickly into space, thus maintaining temperatures suitable for life. It shields us from dangerous ultraviolet radiation from the sun and incinerates most incoming meteors before they can strike the surface. Furthermore, it is the medium through which weather patterns develop, water cycles, and essential gases are exchanged, making it an active participant in every ecological process.

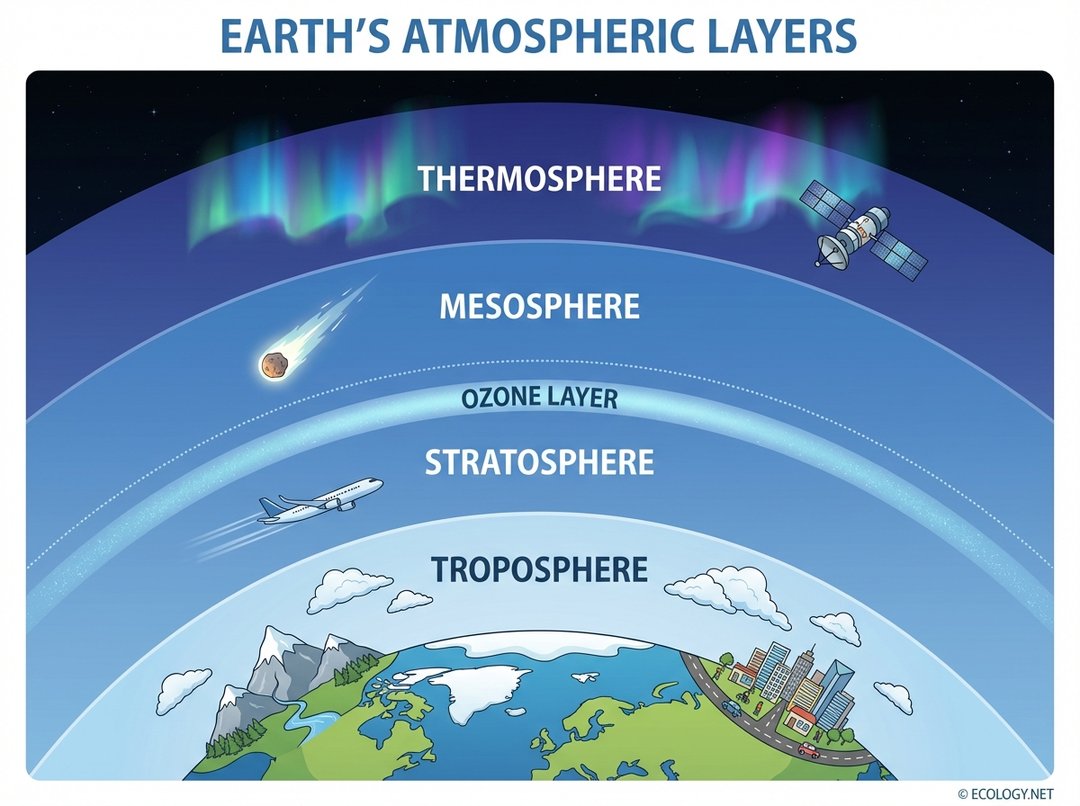

Layers of Protection: Atmospheric Structure

Just as an onion has layers, so too does our atmosphere. These distinct layers are characterized by differences in temperature, composition, and density. Each layer plays a unique role in the overall functioning of this protective shield.

From the ground up, these layers are:

- Troposphere: The Weather Maker

This is the lowest layer, extending from the Earth’s surface up to about 8 to 15 kilometers (5 to 9 miles) high, depending on latitude and season. It is where all of Earth’s weather occurs, from gentle breezes to powerful thunderstorms. The troposphere contains most of the atmosphere’s mass and water vapor. Temperatures generally decrease with altitude in this layer, which is why mountain peaks are colder than valleys.

- Stratosphere: Home of the Ozone Layer

Above the troposphere lies the stratosphere, reaching up to about 50 kilometers (31 miles). Unlike the troposphere, temperatures in the stratosphere actually increase with altitude. This warming is primarily due to the presence of the ozone layer, a region rich in ozone molecules (O3). The ozone layer is critically important because it absorbs most of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation, protecting life on Earth from its damaging effects. Commercial airplanes often fly in the lower stratosphere to avoid turbulence.

- Mesosphere: The Meteor Burner

Extending from about 50 to 85 kilometers (31 to 53 miles) above Earth, the mesosphere is the coldest layer of the atmosphere. Temperatures can plummet to around -90 degrees Celsius (-130 degrees Fahrenheit). This is the layer where most meteors burn up upon entering Earth’s atmosphere, creating the spectacular “shooting stars” we sometimes observe. Without the mesosphere, our planet would be constantly bombarded by space debris.

- Thermosphere: The Aurora Display

The outermost layer, the thermosphere, extends from about 85 kilometers (53 miles) to as high as 600 kilometers (372 miles) or more. While temperatures here can reach extremely high values (over 1,000 degrees Celsius or 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit), it would not feel hot to us because the air is so incredibly thin. The thermosphere is where the beautiful auroras (Northern and Southern Lights) occur, as solar particles collide with atmospheric gases. Many satellites, including the International Space Station, orbit within this layer.

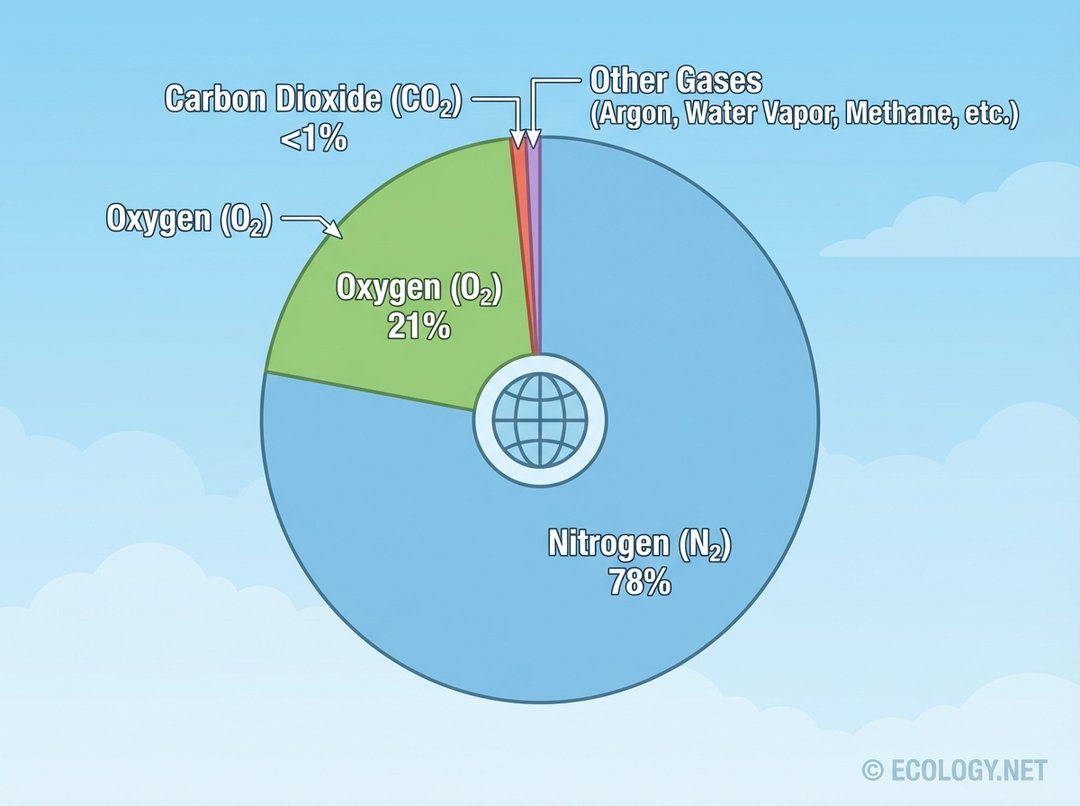

Atmospheric Composition: The Recipe for Life

The atmosphere is a precise blend of gases, each playing a crucial role in maintaining Earth’s habitability. While it might seem like a simple mixture, the proportions of these gases are finely tuned to support life.

The primary components of dry air are:

- Nitrogen (N2): Approximately 78%

Nitrogen is the most abundant gas in our atmosphere. While not directly used for breathing by most organisms, it is an essential component of proteins and nucleic acids, the building blocks of life. Atmospheric nitrogen is converted into usable forms by certain bacteria in a process called nitrogen fixation, making it available to plants and, subsequently, to all other life forms.

- Oxygen (O2): Approximately 21%

Oxygen is vital for aerobic respiration, the process by which most living organisms convert food into energy. It is produced primarily by plants through photosynthesis. The presence of such a high concentration of free oxygen is a unique characteristic of Earth’s atmosphere, a testament to billions of years of biological activity.

- Argon (Ar): Approximately 0.93%

Argon is an inert noble gas, meaning it does not readily react with other elements. While abundant, it has no direct biological role in the atmosphere.

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2): Approximately 0.04%

Despite its small percentage, carbon dioxide is immensely important. It is a key ingredient for photosynthesis, the process by which plants produce their food and release oxygen. CO2 is also a powerful greenhouse gas, meaning it traps heat in the atmosphere, contributing to the planet’s overall temperature regulation. While essential for life, an excess of CO2 can lead to significant climate changes.

- Trace Gases: Water Vapor, Methane, Neon, Helium, Krypton, Hydrogen, Ozone, etc.

These gases are present in much smaller quantities but can have significant impacts. Water vapor, for instance, is a potent greenhouse gas and crucial for the hydrological cycle, forming clouds and precipitation. Methane is another powerful greenhouse gas, while ozone, as mentioned, protects us from UV radiation.

Atmospheric Processes and Ecological Impacts

The atmosphere is not static; it is a dynamic system constantly in motion, driving many of the Earth’s most fundamental processes. These atmospheric dynamics directly shape landscapes, influence biodiversity, and dictate the very existence of ecosystems.

The Engine of Weather and Climate

The uneven heating of Earth’s surface by the sun, combined with the planet’s rotation, creates atmospheric pressure differences that drive wind. Wind, in turn, is a powerful force that:

- Disperses Seeds and Pollen: Many plants rely on wind for reproduction, carrying their seeds or pollen far and wide, enabling colonization of new areas. Think of a dandelion releasing its fluffy seeds into the breeze.

- Shapes Landscapes: Over millennia, wind erosion can sculpt rocks, create sand dunes, and transport vast amounts of dust and sediment, influencing soil composition and fertility in distant regions.

- Influences Ocean Currents: Wind transfers energy to the ocean surface, driving ocean currents that distribute heat around the globe, impacting marine ecosystems and coastal climates.

The atmosphere also plays a central role in the hydrological cycle. Water evaporates from oceans and land, rises into the atmosphere, forms clouds, and eventually returns to Earth as precipitation (rain, snow, sleet, hail). This cycle is fundamental for:

- Watering Ecosystems: Precipitation provides the fresh water necessary for all terrestrial life, sustaining forests, grasslands, and agricultural lands.

- Nutrient Cycling: Rain washes nutrients from the atmosphere and land into soils and waterways, enriching ecosystems.

- Temperature Regulation: Evaporation cools surfaces, and cloud cover can reflect sunlight, influencing local temperatures.

The Atmosphere’s Role in Shaping Ecosystems

The long-term patterns of atmospheric conditions define climate zones, which in turn dictate the types of ecosystems that can thrive in a particular region. From the frigid poles to the scorching deserts and lush rainforests, the atmosphere’s influence is paramount.

- Climate Zones and Biomes: The global distribution of temperature and precipitation, driven by atmospheric circulation, creates distinct climate zones. These zones correspond to major biomes, such as tropical rainforests (high heat, high rain), deserts (high heat, low rain), tundras (low heat, low rain), and temperate forests (moderate heat, moderate rain). Each biome supports a unique array of plant and animal species adapted to its specific atmospheric conditions.

- The Carbon Cycle: The atmosphere is a major reservoir for carbon, primarily in the form of carbon dioxide. This carbon cycles continuously between the atmosphere, oceans, land, and living organisms. Photosynthesis removes CO2 from the atmosphere, while respiration and decomposition release it back. This delicate balance is crucial for regulating Earth’s temperature and providing carbon for life’s building blocks.

- The Nitrogen Cycle: As mentioned, atmospheric nitrogen is fixed by bacteria, making it available to plants. This process is a cornerstone of ecosystem productivity, as nitrogen is a limiting nutrient for plant growth. The atmosphere thus acts as a vast reservoir for this essential element, constantly replenished and utilized by biological processes.

Threats and the Future of Our Atmosphere

Despite its immense resilience, the atmosphere is vulnerable to human activities. Pollution from industrial emissions, vehicle exhaust, and agricultural practices can degrade air quality, leading to health problems and damaging ecosystems. The increased release of greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide and methane, is altering the atmosphere’s composition, leading to global warming and climate change. These changes manifest as more extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and shifts in climate zones, posing significant threats to biodiversity and human societies.

Understanding the intricate workings of the atmosphere is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical step towards informed environmental stewardship. Protecting the health of our atmosphere means safeguarding the future of all life on Earth.

Conclusion: Our Indispensable Atmospheric Blanket

The atmosphere is far more than just the air we breathe; it is a complex, dynamic, and indispensable system that makes Earth a living planet. From its distinct protective layers to its precise gaseous composition and its role as the engine of weather and climate, every aspect of the atmosphere contributes to the intricate web of life. It shields us, sustains us, and shapes the very landscapes we inhabit. Appreciating this invisible blanket is the first step towards understanding our planet’s ecological balance and recognizing our collective responsibility to protect this vital resource for generations to come.