Unlocking Life’s Explosive Power: Understanding Biotic Potential

Imagine a single organism, given everything it needs to thrive, reproducing without limit. How quickly could its descendants fill the Earth? This thought experiment leads us to a fundamental concept in ecology: biotic potential. It is the maximum reproductive capacity of an organism under ideal environmental conditions, representing the highest possible rate of population growth.

Biotic potential is a theoretical ceiling, a measure of how much life can proliferate when all conditions are perfect. In reality, such perfect conditions rarely last, but understanding this inherent capacity helps ecologists predict population dynamics, manage resources, and comprehend the spread of species.

What Exactly is Biotic Potential?

At its core, biotic potential is the inherent ability of a population to increase in number. It is not just about how many offspring an individual can produce, but also how quickly those offspring can reproduce themselves, and how many survive to do so. When resources are abundant, predators are absent, and the climate is favorable, a species can achieve its maximum biotic potential, leading to exponential growth.

The Core Components of Biotic Potential

Several key biological traits contribute to a species’ biotic potential:

- Reproductive Rate: This includes the number of offspring produced per reproductive event, the frequency of reproduction, and the age at which an individual can first reproduce. Species that produce many offspring frequently and at a young age tend to have higher biotic potential.

- Survival Rate: The proportion of offspring that survive to reproductive age is crucial. If many offspring die young, the effective biotic potential is reduced. Ideal conditions minimize mortality.

- Generation Time: This refers to the average time between the birth of an individual and the birth of its offspring. Shorter generation times allow populations to grow much faster, even if the number of offspring per event is not exceptionally high.

Nature’s Extremes: Rabbits, Elephants, and the Spectrum of Life

The natural world offers a vivid spectrum of biotic potential, often categorized into two broad life history strategies: r-selected and K-selected species. R-selected species are those with high biotic potential, focusing on producing many offspring with little parental care, hoping a few will survive. K-selected species, conversely, invest heavily in fewer offspring, providing extensive parental care to ensure their survival.

Consider the striking difference between rabbits and elephants. Rabbits are a classic example of an r-selected species. They mature quickly, have short gestation periods, produce large litters multiple times a year, and offer relatively little parental investment per individual offspring. Under ideal conditions, a rabbit population can explode in numbers.

Elephants, on the other hand, are K-selected giants. They have long gestation periods, typically give birth to a single calf, and invest years in nurturing and protecting their young. Their reproductive rate is low, and their population growth is inherently slow, even in the best environments.

The image above starkly illustrates this contrast. On one side, a thriving rabbit colony in a lush meadow symbolizes rapid reproduction and high survival under favorable conditions, showcasing high biotic potential. On the other, a small herd of elephants in a dry savannah represents a species with a much lower reproductive rate and slower population growth, even with significant parental investment.

The Microscopic Marvel: Bacterial Biotic Potential

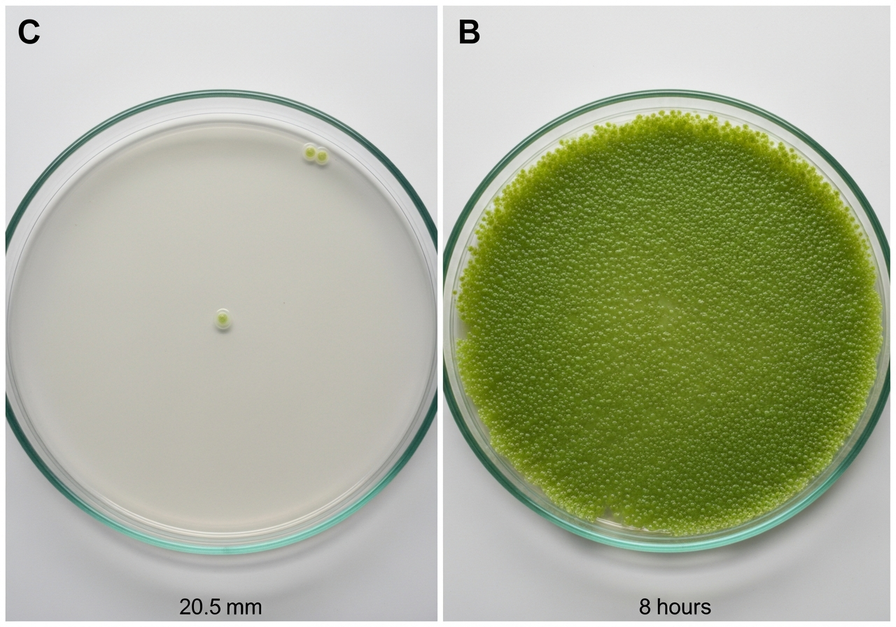

To truly grasp the concept of biotic potential, one must look to the microscopic world. Bacteria exemplify an almost unimaginable capacity for rapid reproduction. Under ideal conditions, many bacterial species can divide every 20 minutes. This means that a single bacterium can become two in 20 minutes, four in 40 minutes, eight in an hour, and so on.

This exponential growth is staggering. In just a few hours, a single bacterial cell can give rise to millions, or even billions, of descendants. This incredible speed of reproduction, combined with a short generation time, makes bacteria a prime example of extremely high biotic potential.

The image demonstrates this phenomenon perfectly. The left panel shows the nascent stage, perhaps a single bacterial colony just beginning to divide. The right panel, after only a few hours, reveals a petri dish almost entirely covered by a dense, vibrant bacterial lawn. This visual transformation powerfully conveys how quickly a population with high biotic potential can expand from a single cell to countless millions.

When Biotic Potential Runs Wild: The Case of Invasive Species

Biotic potential is not just an academic concept; it has profound real-world implications, particularly in the context of invasive species. When a species with high biotic potential is introduced to a new environment where its natural predators, diseases, and competitors are absent, and resources are plentiful, its population can grow unchecked.

This lack of environmental resistance allows the invasive species to realize much of its biotic potential, often leading to explosive population growth that outcompetes native species, disrupts ecosystems, and causes significant economic damage.

The image of zebra mussels in the Great Lakes is a stark reminder of this ecological challenge. These mollusks, introduced from Eastern Europe, possess a high biotic potential. They reproduce rapidly, attach to almost any hard surface, and have few natural predators in their new environment. The result is a dense carpet of mussels, outcompeting native species for food and habitat, clogging water intake pipes, and altering the entire aquatic ecosystem.

The Dance of Life and Limits: Biotic Potential Meets Environmental Resistance

While biotic potential describes a species’ maximum capacity for growth, it is rarely achieved in nature for long. Populations are constantly constrained by what ecologists call environmental resistance. This refers to all the factors that limit population growth, preventing it from reaching its theoretical maximum.

Factors of Environmental Resistance

- Limited Resources: Scarcity of food, water, shelter, or space is a primary limiting factor.

- Predation: Predators naturally keep prey populations in check.

- Disease: Pathogens can decimate populations, especially when they become dense.

- Competition: Individuals within a species, or between different species, compete for the same limited resources.

- Adverse Climate: Unfavorable temperatures, extreme weather events, or lack of suitable habitat can reduce survival and reproduction.

The interplay between biotic potential and environmental resistance determines a population’s carrying capacity, which is the maximum population size that a particular environment can sustain indefinitely without degradation.

From Theory to Reality: The Ecological Significance

Understanding biotic potential is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical tool for addressing many ecological and environmental challenges:

- Conservation Biology: Knowing the biotic potential of endangered species helps in designing effective breeding programs and estimating recovery rates.

- Pest Control: For agricultural pests or disease vectors, understanding their high biotic potential is key to developing strategies that can effectively manage or suppress their rapid population growth.

- Resource Management: In fisheries or forestry, knowledge of biotic potential helps in setting sustainable harvest limits to prevent overexploitation and ensure populations can rebound.

- Invasive Species Management: Identifying species with high biotic potential that could become invasive allows for proactive measures to prevent their introduction or rapid spread.

- Climate Change Impacts: Biotic potential can influence how quickly species can adapt or shift their ranges in response to changing climatic conditions.

The Mathematical Heart of Population Dynamics

For a more in-depth understanding, biotic potential is a fundamental parameter in mathematical models of population growth. The simplest model, exponential growth, assumes unlimited resources and no environmental resistance, allowing a population to grow at its maximum biotic potential. This is often represented by the equation dN/dt = rN, where ‘r’ is the intrinsic rate of natural increase, directly reflecting biotic potential.

However, real-world populations typically follow a logistic growth model, which incorporates environmental resistance and the concept of carrying capacity. This model shows an initial period of exponential growth, followed by a slowing rate as the population approaches the carrying capacity of its environment. The biotic potential, or ‘r’ value, remains a crucial component of this more realistic model, determining the initial steepness of the growth curve before environmental limits take hold. Ecologists use these models to predict future population sizes, assess the impact of environmental changes, and formulate management strategies for both wildlife and human populations.

Conclusion: A Fundamental Force in Ecology

Biotic potential is a powerful, inherent force driving life on Earth, representing the maximum capacity for population growth under ideal conditions. From the rapid proliferation of bacteria to the measured pace of elephant reproduction, it shapes the dynamics of ecosystems and the very fabric of biodiversity. While rarely fully realized due to environmental resistance, understanding this fundamental concept is indispensable for ecologists, conservationists, and anyone seeking to comprehend the intricate balance of life on our planet.