Life on Earth is a testament to the incredible diversity of strategies organisms employ to ensure their survival and the continuation of their species. At the heart of this perpetuation lies reproduction, a fundamental biological process that takes myriad forms across the tree of life. Understanding these diverse reproductive strategies is crucial for comprehending how species adapt, evolve, and interact within their ecosystems. From microscopic bacteria to colossal whales, every organism has a unique approach to passing on its genetic legacy, shaped by millions of years of evolutionary pressures.

Reproductive strategies encompass a wide array of decisions and adaptations related to how an organism produces offspring. These include the number of offspring, the frequency of reproduction, the amount of parental care provided, and even the method of reproduction itself. These choices are not random; they are finely tuned responses to environmental conditions, resource availability, predation risk, and competition. Let us delve into the fascinating world of reproductive strategies, exploring the fundamental distinctions and the intricate adaptations that allow life to flourish.

The Fundamental Divide: Asexual vs. Sexual Reproduction

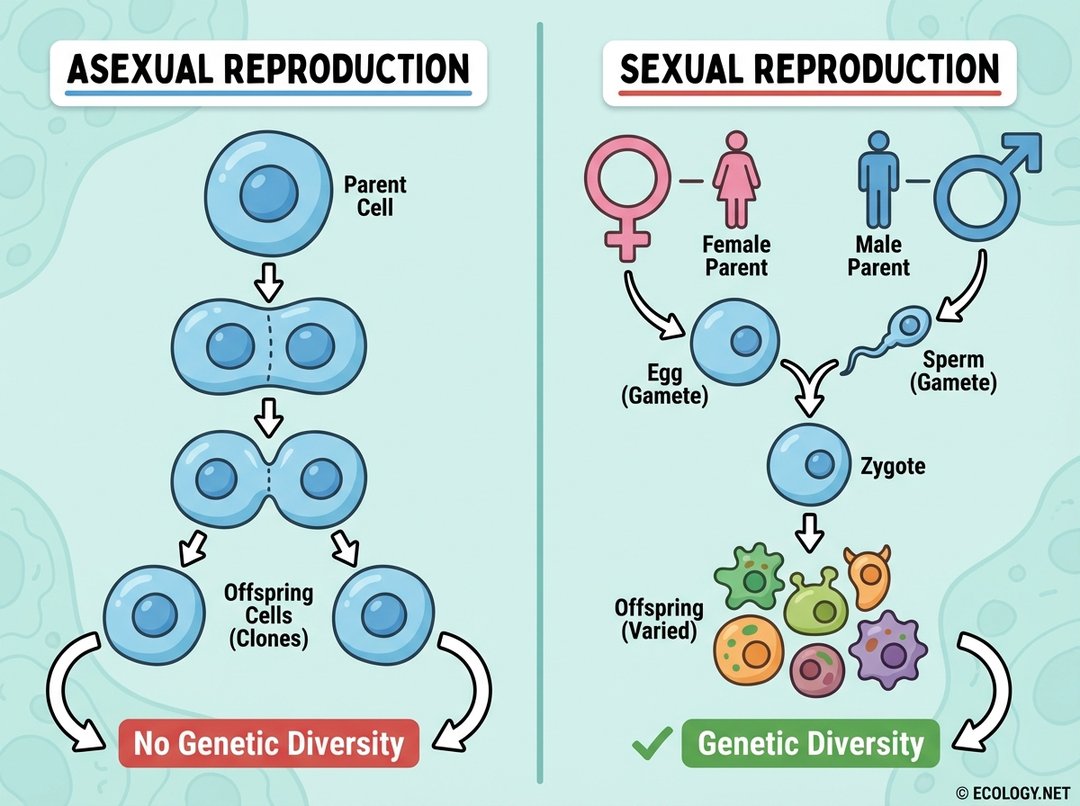

One of the most basic distinctions in reproductive strategies lies in whether an organism reproduces with or without a partner. This dichotomy defines the two primary modes of reproduction: asexual and sexual.

Asexual Reproduction: Efficiency and Speed

Asexual reproduction involves a single parent producing offspring that are genetically identical to itself. This method is common among single-celled organisms like bacteria and amoebas, but also occurs in many plants and some animals. The process is often rapid and efficient, requiring no mate search or complex reproductive organs.

- Binary Fission: A single cell simply divides into two identical daughter cells, as seen in bacteria.

- Budding: A new organism grows out from the body of the parent, eventually detaching, like in yeast or hydras.

- Fragmentation: A parent organism breaks into pieces, each capable of developing into a new individual, common in starfish and some worms.

- Parthenogenesis: Development of an embryo from an unfertilized egg, observed in some insects, fish, and reptiles.

The primary advantage of asexual reproduction is its speed and simplicity. Organisms can rapidly colonize new environments or exploit abundant resources without the energetic cost of finding a mate. However, this efficiency comes at a significant cost: a lack of genetic diversity. Since offspring are clones of the parent, they share the same vulnerabilities. If environmental conditions change or a new pathogen emerges, an entire population could be wiped out because no individuals possess the genetic variations needed to adapt.

Sexual Reproduction: Diversity is Key

In contrast, sexual reproduction involves two parents contributing genetic material to produce offspring that are genetically unique. This typically involves the fusion of specialized reproductive cells called gametes, such as sperm and egg. The process of meiosis, which produces gametes, shuffles genes, and fertilization combines genetic material from two different individuals, leading to offspring with novel combinations of traits.

The immense benefit of sexual reproduction is the generation of genetic diversity. This variation acts as a crucial buffer against environmental changes. In a population of sexually reproducing organisms, some individuals are more likely to possess traits that allow them to survive new challenges, ensuring the species’ long-term persistence. While sexual reproduction often requires more energy, time, and resources for mate finding, courtship, and sometimes parental care, its evolutionary advantage in adaptability is profound.

Life’s Trade-offs: r-Selected vs. K-Selected Strategies

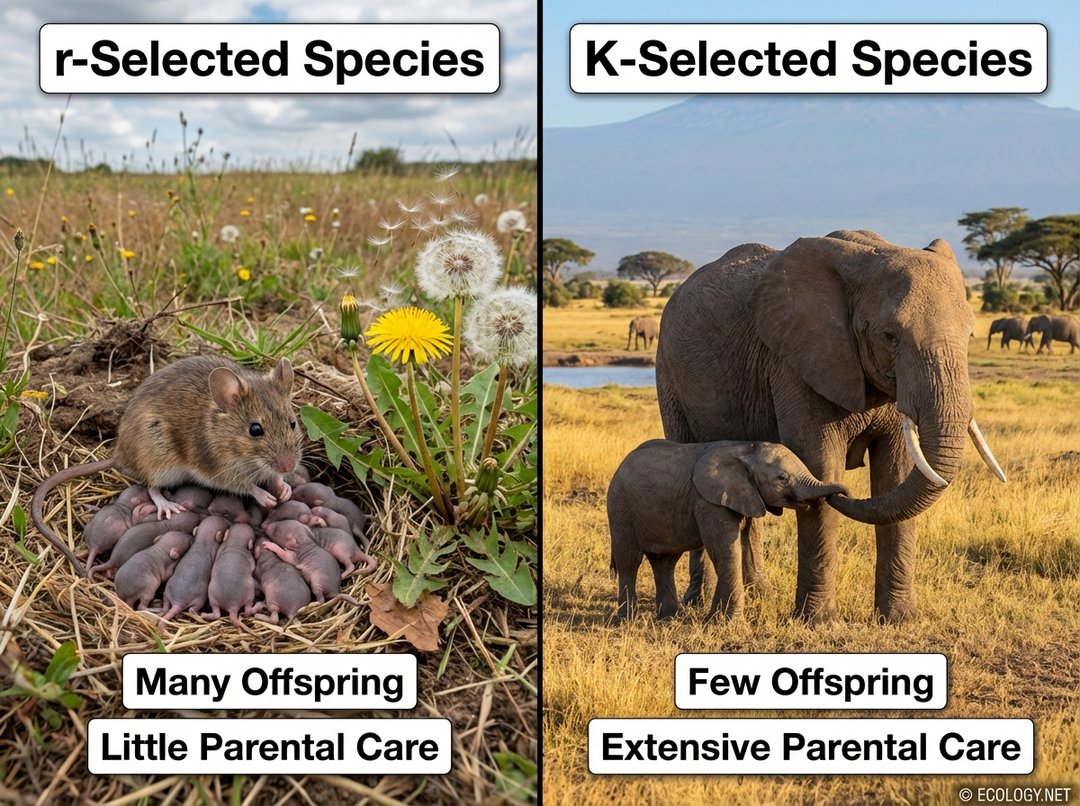

Beyond the fundamental choice between asexual and sexual reproduction, species also exhibit a spectrum of life history strategies, often categorized as r-selected or K-selected. These terms describe a continuum of reproductive approaches that reflect different trade-offs between the number of offspring produced and the investment in each offspring.

The r-Strategists: Quantity Over Quality

Species employing an r-selected strategy prioritize producing a large number of offspring with minimal individual parental investment. The ‘r’ in r-selection refers to the intrinsic rate of natural increase, emphasizing rapid population growth. These organisms typically live in unstable or unpredictable environments where resources can fluctuate dramatically. Their strategy is to flood the environment with offspring, hoping that at least a few will survive to reproductive age.

Characteristics of r-selected species include:

- Many offspring: Producing hundreds, thousands, or even millions of eggs or seeds.

- Small body size: Often smaller organisms with shorter lifespans.

- Early maturity: Reaching reproductive age quickly.

- Little to no parental care: Offspring are largely left to fend for themselves.

- High mortality rate: A very small percentage of offspring survive to adulthood.

- Pioneer species: Excellent at colonizing new or disturbed habitats.

Classic examples of r-selected species include insects like mosquitoes and flies, many types of fish (e.g., cod laying millions of eggs), rodents such as mice, and plants like dandelions. These species are masters of rapid reproduction and dispersal, quickly exploiting transient opportunities.

The K-Strategists: Quality Over Quantity

In contrast, K-selected species invest heavily in a small number of offspring. The ‘K’ in K-selection refers to the carrying capacity of the environment, indicating that these populations tend to be stable and near the maximum number of individuals the environment can support. These organisms typically thrive in stable, predictable environments where competition for resources is high.

Characteristics of K-selected species include:

- Few offspring: Producing only one or a handful of offspring at a time.

- Large body size: Often larger organisms with longer lifespans.

- Late maturity: Taking a longer time to reach reproductive age.

- Extensive parental care: Providing significant investment in nurturing and protecting offspring.

- Low mortality rate: A high percentage of offspring survive to adulthood.

- Strong competitors: Well-adapted to stable environments with established populations.

Elephants, whales, humans, large trees like oaks, and many birds are prime examples of K-selected species. Their strategy ensures that the few offspring they produce have the best possible chance of survival and successful reproduction themselves, often through extended periods of learning and development under parental guidance.

It is important to remember that r- and K-selection represent two ends of a spectrum. Most species fall somewhere in between, exhibiting a mix of traits depending on their specific ecological niche and environmental pressures.

Beyond Survival: The Role of Sexual Selection and Mating Systems

While the r/K distinction focuses on the quantity versus quality of offspring, sexual reproduction introduces another layer of complexity: the competition for mates and the evolution of traits that enhance mating success. This is where sexual selection comes into play, often leading to spectacular and sometimes seemingly counterintuitive adaptations.

The Power of Attraction: Sexual Selection

Sexual selection is a form of natural selection where individuals with certain inherited characteristics are more likely than other individuals to obtain mates. It often results in the evolution of exaggerated traits that may seem detrimental to survival, but are highly advantageous for reproduction.

Sexual selection can manifest in two main ways:

- Intrasexual selection: Competition among individuals of the same sex for mates. This often involves direct combat or ritualized displays of strength, leading to the evolution of weapons like antlers in deer or large body size in seals.

- Intersexual selection: Individuals of one sex (typically females) choose mates from the other sex. This often drives the evolution of elaborate courtship displays, bright coloration, or complex songs, as seen in many bird species.

The male peacock’s magnificent tail is a classic example of intersexual selection. While cumbersome and energetically costly, a large, vibrant tail signals health, genetic quality, and an ability to survive despite the handicap, making the male more attractive to peahens. Similarly, the elaborate songs of many male birds serve to attract females and ward off rivals.

Mating Systems: A Spectrum of Strategies

The way individuals pair up for reproduction also constitutes a crucial reproductive strategy, known as a mating system. These systems are shaped by factors such as parental investment, resource distribution, and the operational sex ratio (the ratio of reproductively active males to females).

- Monogamy: A single male mates with a single female. This often occurs when biparental care is essential for offspring survival, such as in many bird species where both parents are needed to incubate eggs and feed chicks.

- Polygyny: One male mates with multiple females. This is common when males can monopolize access to multiple females, perhaps by defending a rich territory or a harem of females. Examples include lions and elephant seals.

- Polyandry: One female mates with multiple males. This is much rarer and often occurs when males provide most or all of the parental care, allowing females to lay multiple clutches of eggs with different partners, as seen in some shorebirds.

- Promiscuity: Both males and females mate with multiple partners, with no strong pair bonds formed. This can occur in species where parental care is minimal or absent, and individuals simply maximize their chances of fertilization.

Each mating system represents an evolutionary compromise, balancing the benefits of increased reproductive output with the costs of competition, parental investment, and mate guarding. The diversity of these systems highlights the incredible adaptability of life to different ecological pressures.

Conclusion

Reproductive strategies are not merely biological curiosities; they are the very engine of evolution and the foundation of biodiversity. From the rapid cloning of bacteria to the elaborate courtship dances of birds, every strategy is a finely tuned response to the challenges and opportunities presented by the environment. Understanding these strategies helps us appreciate the intricate web of life, predict how species might respond to environmental changes, and even inform conservation efforts. The ongoing dance of life, with its myriad reproductive approaches, ensures that the planet remains a vibrant and ever-evolving tapestry of existence.