Beneath our feet lies a world teeming with life and essential for nearly all terrestrial ecosystems: soil. Far from being mere dirt, soil is a complex, dynamic, and living system, a masterpiece of natural engineering. Understanding its composition is not just for scientists; it is fundamental for gardeners, farmers, environmentalists, and anyone who appreciates the intricate web of life on Earth. Let us embark on a journey to uncover the secrets of soil, from its basic building blocks to its intricate layers and textures.

The Building Blocks of Soil: A Fundamental Mix

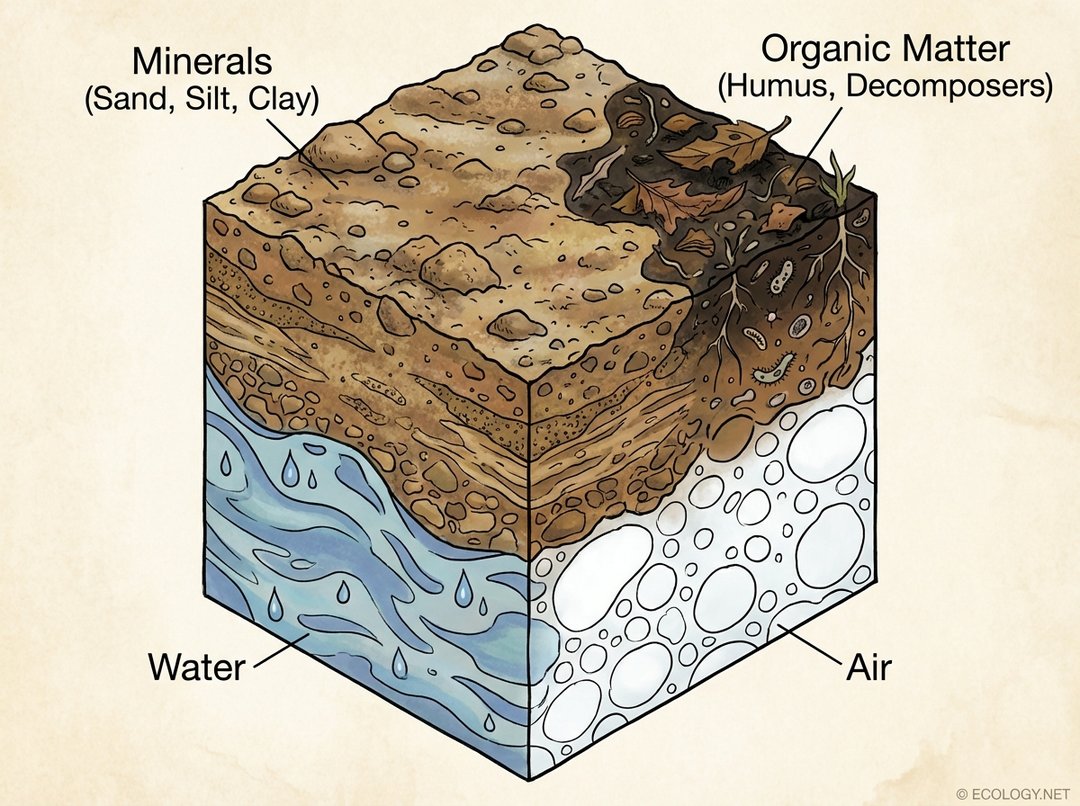

Imagine soil as a carefully crafted recipe, where each ingredient plays a vital role. At its core, soil is composed of four main components, each contributing to its unique properties and functions. These components are not static; they are constantly interacting and changing, creating the dynamic environment we call soil.

The four main components are:

- Minerals: These are the inorganic backbone of soil, derived from weathered rock. They include particles of varying sizes, primarily sand, silt, and clay.

- Water: Essential for all life, water fills the pore spaces between soil particles, making nutrients available to plants and supporting microbial activity.

- Air: Just like water, air occupies the pore spaces. Oxygen in the soil is crucial for root respiration and the activity of beneficial microorganisms.

- Organic Matter: This is the living and once-living component, including decaying plant and animal material, as well as the vast community of microorganisms.

These four components exist in varying proportions, creating different soil types with distinct characteristics. A healthy soil typically has a balanced mix, allowing for good drainage, aeration, and nutrient availability.

The Earth’s Skin: Unveiling Soil Horizons

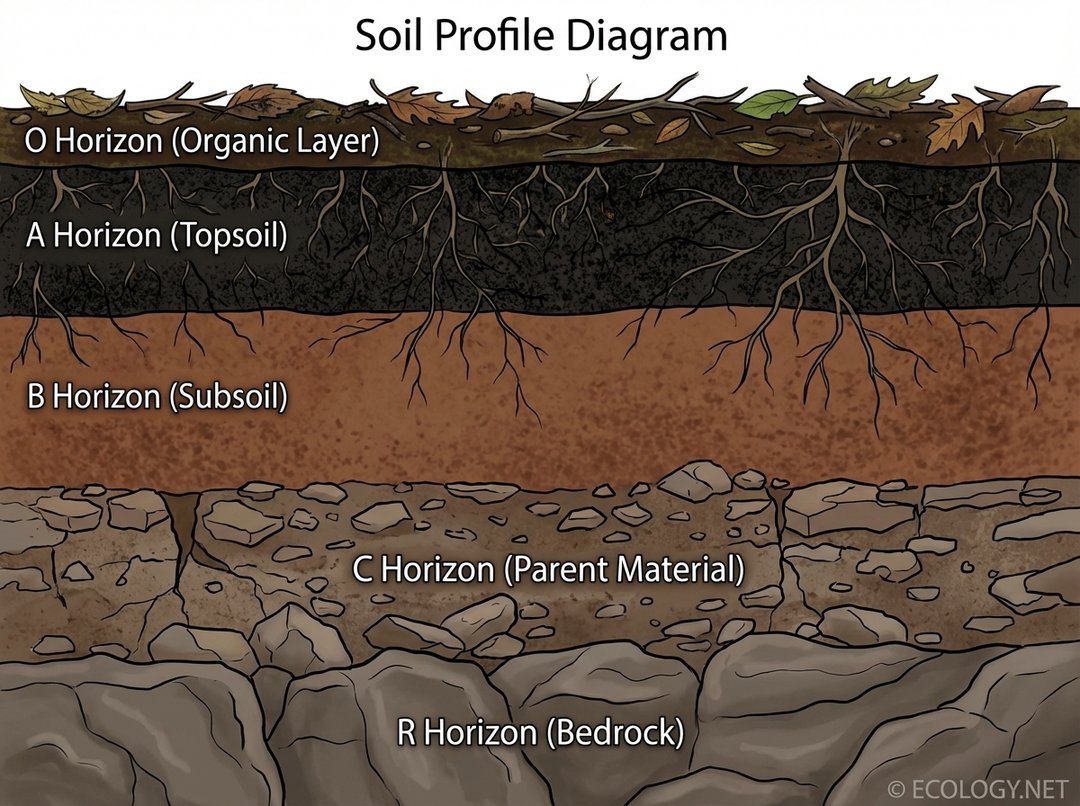

If you were to dig a trench deep into the ground, you would quickly notice that soil is not uniform from top to bottom. Instead, it is organized into distinct horizontal layers, much like the layers of a cake. These layers, known as soil horizons, develop over long periods through the interplay of climate, organisms, topography, parent material, and time. Each horizon has unique physical, chemical, and biological characteristics.

Let us explore these fascinating layers, starting from the surface:

- O Horizon (Organic Layer): This topmost layer is dominated by organic material. It consists of fresh and partially decomposed plant and animal residues, such as fallen leaves, twigs, and dead insects. It is a bustling hub of decomposition, where fungi and bacteria break down organic matter, enriching the soil below. Think of it as nature’s compost pile.

- A Horizon (Topsoil): Often referred to as the topsoil, this layer is typically dark in color due to a high concentration of decomposed organic matter, or humus, mixed with mineral particles. It is the most fertile layer, rich in nutrients, and where most plant roots grow and thrive. This is the layer that farmers cherish and gardeners cultivate.

- B Horizon (Subsoil): Lying beneath the topsoil, the subsoil is generally lighter in color and denser. It accumulates minerals leached from the A horizon, such as clay, iron oxides, and aluminum. While it contains less organic matter than the A horizon, it can still be important for nutrient storage and water retention, especially for plants with deeper root systems.

- C Horizon (Parent Material): This layer consists of partially weathered rock or unconsolidated sediment from which the upper soil layers developed. It shows minimal biological activity and is largely unaffected by the processes that form the O, A, and B horizons. It is the raw material from which soil is born.

- R Horizon (Bedrock): The deepest layer, the R horizon, is composed of solid, unweathered rock. This bedrock serves as the ultimate parent material for the soil above, slowly breaking down over geological timescales to contribute to the C horizon.

The Feel of Soil: Understanding Soil Texture

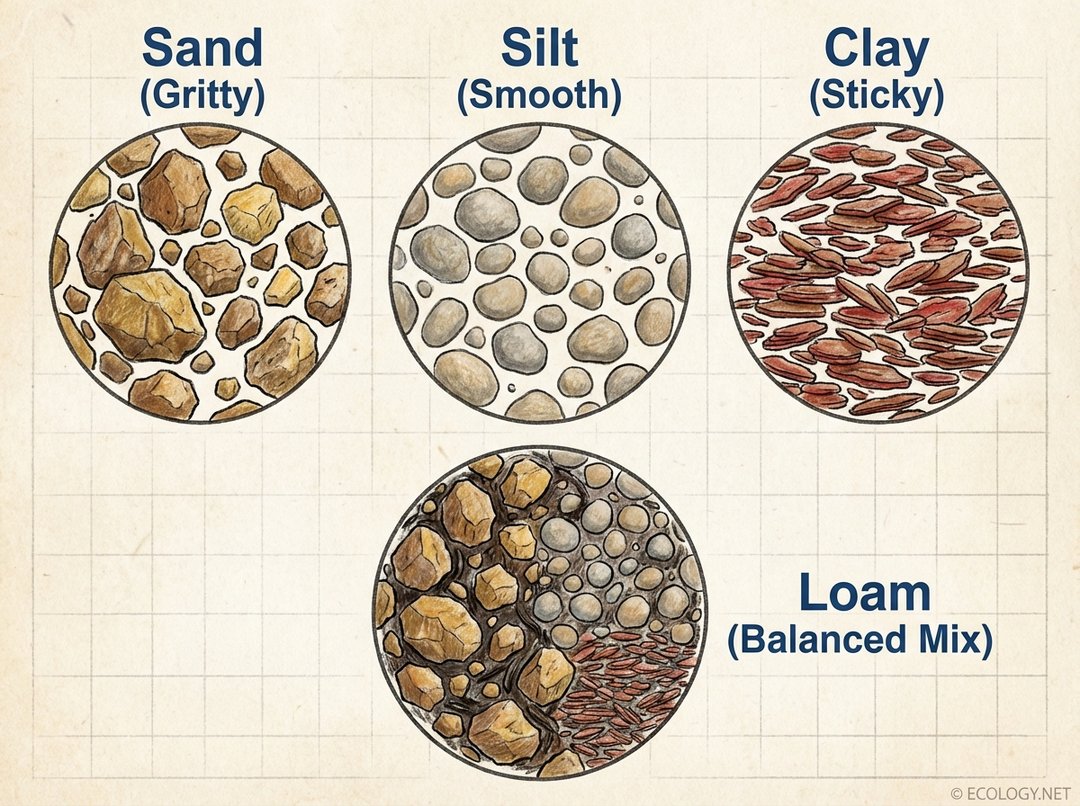

The mineral component of soil, derived from the weathering of rocks, is categorized by particle size. These particles are not all created equal; their size dictates many of soil’s fundamental properties, including how it feels, how well it holds water, and how easily air can move through it. The relative proportions of these mineral particles define the soil’s texture.

The Three Main Mineral Particles:

- Sand: These are the largest soil particles, ranging from 0.05 to 2.0 mm in diameter. Sand particles feel gritty to the touch. Because of their size, they create large pore spaces in the soil, allowing water to drain quickly and air to circulate freely. Sandy soils warm up fast in spring but also dry out rapidly and have low nutrient retention. Think of beach sand.

- Silt: Intermediate in size, silt particles range from 0.002 to 0.05 mm. Silt feels smooth and floury when dry, and slippery when wet. Silt particles create smaller pore spaces than sand, leading to better water retention than sandy soils, but still allowing for good drainage and aeration. Silt-rich soils are often very fertile.

- Clay: These are the smallest soil particles, less than 0.002 mm in diameter. Clay particles are plate-like and feel sticky when wet and hard when dry. Their tiny size means they pack together tightly, creating very small pore spaces. This results in high water retention (often leading to waterlogging) and excellent nutrient-holding capacity, but poor drainage and aeration.

The Ideal Mix: Loam

While soils can be predominantly sandy, silty, or clayey, the most desirable soil for agriculture and gardening is often loam. Loam is a balanced mixture of sand, silt, and clay, typically with roughly equal proportions of sand and silt, and a smaller but significant amount of clay. This balance provides the best of all worlds:

- Good drainage and aeration from sand.

- Good water retention and nutrient availability from silt.

- Nutrient-holding capacity and some structure from clay.

Loamy soils are easy to work, hold moisture well without becoming waterlogged, and are rich in nutrients, making them highly productive.

Beyond the Basics: The Dynamic Role of Organic Matter

While minerals provide the structure, organic matter is the lifeblood of soil. It is a complex mixture of decomposed plant and animal residues, living organisms, and the byproducts of their activity. This component, though often a small percentage by weight, has a disproportionately large impact on soil health and fertility.

Key Aspects of Organic Matter:

- Humus: This is the stable, dark, highly decomposed organic material that gives healthy topsoil its rich, dark color. Humus acts like a sponge, significantly increasing the soil’s capacity to hold water and nutrients. It also improves soil structure, making it more resistant to erosion and compaction.

- Nutrient Cycling: As organic matter decomposes, it releases essential plant nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur in forms that plants can absorb. This continuous process is vital for sustaining plant growth without constant external inputs.

- Microbial Habitat: Organic matter provides food and shelter for an astonishing diversity of soil organisms, from bacteria and fungi to earthworms and insects. These decomposers are the unsung heroes of the soil, driving nutrient cycles and improving soil structure. A single teaspoon of healthy soil can contain billions of microorganisms.

- Buffering Capacity: Organic matter helps buffer soil pH, making it more stable and less prone to drastic changes that could harm plants.

Consider a forest floor: the thick layer of decaying leaves and wood is a prime example of the O horizon, rich in organic matter. This layer slowly breaks down, feeding the trees and plants above, illustrating the continuous cycle of life and decomposition.

The Invisible Architects: Water and Air in Soil

Often overlooked because they are unseen, soil water and soil air are as critical as the solid components. They fill the pore spaces between mineral and organic particles, creating the dynamic environment necessary for life.

- Soil Water: Water is the universal solvent, dissolving nutrients and transporting them to plant roots. It is essential for photosynthesis and maintaining plant turgor. The amount of water a soil can hold depends heavily on its texture and organic matter content. Clay soils and soils rich in humus hold more water, while sandy soils drain quickly.

- Soil Air: Just like humans need oxygen, plant roots and most soil organisms require oxygen for respiration. Soil air provides this vital gas. Well-aerated soils allow roots to breathe and beneficial aerobic microbes to thrive. Compacted soils, or waterlogged soils where all pore spaces are filled with water, lack sufficient air, leading to stressed roots and the proliferation of anaerobic organisms, which can produce harmful compounds.

The balance between water and air is crucial. Too much water leads to waterlogging and oxygen deprivation; too little leads to drought. A healthy soil structure, with a good mix of large and small pores, ensures an optimal balance, allowing for both adequate water retention and good aeration.

Why Soil Composition Matters: Practical Insights

Understanding soil composition is not just academic; it has profound practical implications for everything from backyard gardening to global food security and environmental health.

- For Gardeners and Farmers:

- Plant Selection: Knowing your soil type helps you choose plants that will thrive. For example, lavender prefers well-drained, sandy soils, while hydrangeas often do better in soils with more clay and organic matter that retain moisture.

- Water Management: Sandy soils require more frequent watering but less volume per session, while clay soils need less frequent but deeper watering to avoid runoff and compaction.

- Nutrient Management: Soils rich in organic matter and clay have a higher capacity to hold nutrients, reducing the need for frequent fertilization.

- Soil Amendments: If your soil is too sandy, adding organic matter can improve water and nutrient retention. If it is too clayey, organic matter can improve drainage and aeration, making it easier to work.

- For Environmental Health:

- Erosion Control: Soils with good structure and high organic matter content are more resistant to erosion by wind and water, protecting landscapes and waterways.

- Water Filtration: Soil acts as a natural filter, purifying water as it percolates through its layers, removing pollutants before they reach groundwater.

- Carbon Sequestration: Healthy soils, especially those rich in organic matter, play a significant role in mitigating climate change by storing carbon from the atmosphere.

- Biodiversity: Soil is home to a quarter of all known species on Earth. Its composition directly impacts the biodiversity it can support, which in turn contributes to ecosystem stability and resilience.

Imagine trying to grow carrots in heavy clay soil. The dense, sticky texture would make it difficult for the roots to penetrate and expand, resulting in stunted, misshapen vegetables. Conversely, growing water-loving plants in pure sand would require constant irrigation, highlighting the importance of matching plants to their preferred soil composition.

Conclusion: The Unseen Foundation of Life

Soil, often taken for granted, is a marvel of natural complexity. Its composition, a delicate balance of minerals, organic matter, water, and air, dictates its ability to support life, filter water, and regulate climate. From the distinct layers of its horizons to the microscopic differences in its particles, every aspect of soil composition plays a critical role in the health of our planet.

By understanding and appreciating the intricate world beneath our feet, we can make more informed decisions about how we manage our land, grow our food, and protect our environment. The next time you walk across a field or tend to your garden, take a moment to consider the incredible, dynamic system that is soil composition, the unseen foundation upon which all terrestrial life depends.