The relationship between humanity and the natural world has always been complex, evolving from one of survival and dominance to a growing recognition of interdependence and shared fate. At the heart of this evolution lies environmental ethics, a vital field of philosophy that explores the moral relationship of human beings to, and also the value and moral status of, the environment and its nonhuman contents. It asks profound questions: Do we have a moral obligation to protect nature? If so, to what extent, and for whose benefit?

Understanding environmental ethics is not merely an academic exercise; it is fundamental to addressing the most pressing ecological challenges of our time, from climate change and biodiversity loss to resource depletion and pollution. It provides the framework for making responsible decisions that impact the planet and all its inhabitants.

Foundations of Environmental Concern

For much of human history, the natural world was often viewed primarily as a resource to be utilized for human benefit. Early societies, while often holding spiritual reverence for nature, still largely operated under a paradigm where human needs took precedence. The advent of the Industrial Revolution amplified this perspective, leading to unprecedented rates of resource extraction, pollution, and habitat destruction. Forests were cleared for timber and agriculture, rivers became conduits for waste, and the air grew thick with industrial emissions.

However, as the scale of human impact became undeniable, a shift in consciousness began to emerge. Thinkers and activists started to question the prevailing anthropocentric, or human-centered, view. Early conservation movements, initially focused on preserving natural beauty or resources for future human use, gradually broadened their scope to consider the intrinsic value of nature itself. This growing awareness laid the groundwork for what we now understand as environmental ethics, moving beyond mere utility to moral consideration.

This historical shift, from a resource-centric approach to one recognizing ethical obligations towards the environment, marks a pivotal moment in our collective understanding. It highlights the journey from viewing nature as an endless supply of commodities to acknowledging its delicate balance and our profound responsibility within it.

Core Ethical Frameworks: How We Value Nature

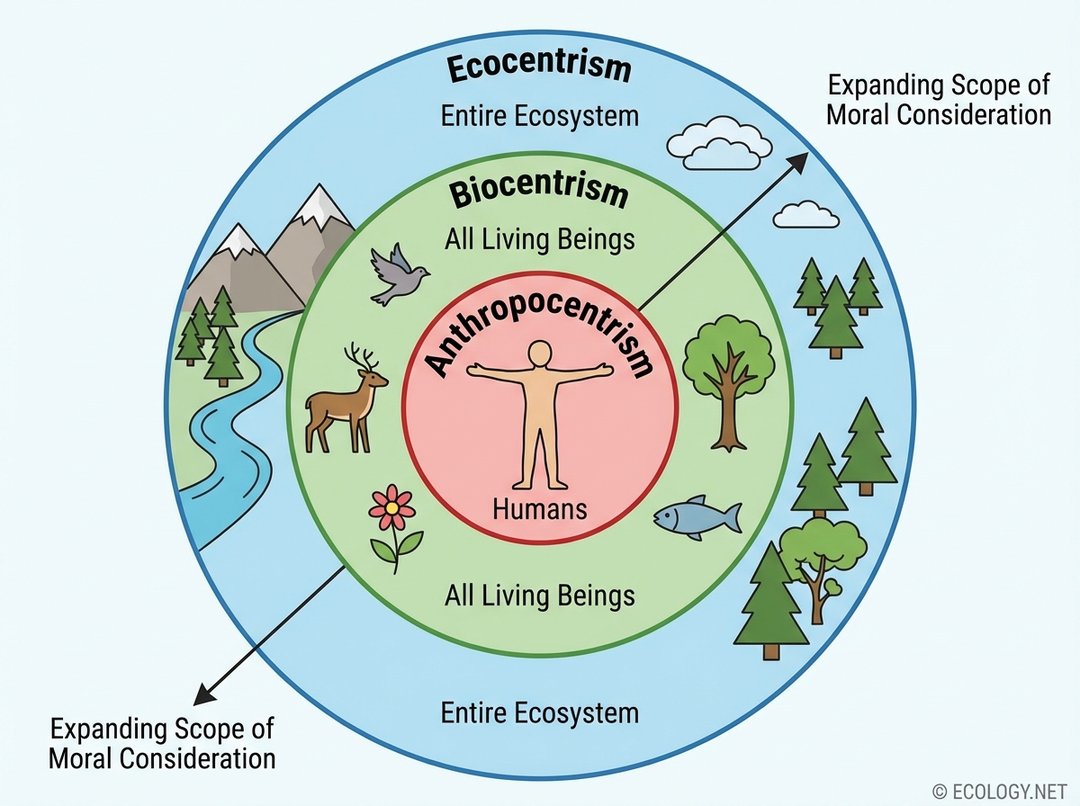

Environmental ethics is built upon several foundational frameworks, each offering a distinct perspective on who or what deserves moral consideration. These frameworks help us categorize and understand different approaches to environmental decision-making.

Anthropocentrism: Human-Centered Ethics

Anthropocentrism, derived from the Greek words “anthropos” (human) and “kentron” (center), places human beings at the center of moral consideration. In this view, the environment is valued primarily for its usefulness to humans. Nature’s worth is instrumental, meaning it serves as a tool or resource for human well-being, survival, and prosperity.

- Key Idea: Only humans have intrinsic value; everything else has value based on its utility to humans.

- Examples:

- Protecting a forest because it provides timber, clean air, and recreational opportunities for people.

- Conserving a species because it might hold a cure for human disease or contribute to agricultural productivity.

- Implementing pollution controls to safeguard human health and property.

While often criticized for its potential to justify exploitation, a “enlightened anthropocentrism” can still advocate for environmental protection, arguing that a healthy environment is ultimately essential for long-term human survival and quality of life.

Biocentrism: Life-Centered Ethics

Biocentrism expands the circle of moral consideration to include all living beings. It posits that all forms of life, not just humans, possess intrinsic value and therefore deserve moral respect. This perspective challenges the idea of human superiority and emphasizes the interconnectedness of all life.

- Key Idea: All living organisms have intrinsic value, regardless of their utility to humans.

- Examples:

- Advocating for animal rights and welfare, arguing against practices that cause unnecessary suffering to animals.

- Protecting endangered species simply because they have a right to exist, not just for their potential benefit to humans.

- Minimizing human impact on ecosystems to allow all life forms to thrive naturally.

Biocentrism often leads to a strong emphasis on biodiversity conservation and a reevaluation of human consumption patterns that impact other life forms.

Ecocentrism: Ecosystem-Centered Ethics

Ecocentrism takes the broadest view, extending moral consideration beyond individual organisms to entire ecosystems, including non-living components like rivers, mountains, and the atmosphere. It sees the ecosystem as a complex, interconnected web of life and processes, where the health and integrity of the whole are paramount.

- Key Idea: The entire ecosystem, including its living and non-living components, has intrinsic value and deserves moral consideration.

- Examples:

- Protecting an entire watershed, including its forests, rivers, and soil, to maintain its ecological functions and integrity.

- Restoring degraded landscapes to their natural state, even if it means limiting human access or use.

- Implementing policies that prioritize ecosystem health over short-term economic gains, such as preserving old-growth forests for their ecological services.

Ecocentrism often aligns with concepts like the “Land Ethic” proposed by Aldo Leopold, which suggests that humans are merely plain members and citizens of the land community, not its conquerors.

Key Concepts and Principles in Environmental Ethics

Beyond the core frameworks, several important concepts and principles guide ethical reasoning in environmental matters.

Intrinsic vs. Instrumental Value

This distinction is crucial in environmental ethics:

- Intrinsic Value: Something has intrinsic value if it is valuable in itself, for its own sake, regardless of its usefulness to others. Many environmental ethicists argue that nature, or at least living beings within it, possess intrinsic value.

- Instrumental Value: Something has instrumental value if it is valuable as a means to an end, for what it can do for something else. For example, a tree has instrumental value if it provides timber or shade for humans.

The debate over whether nature holds intrinsic value is central to many environmental controversies, influencing how we prioritize conservation efforts versus resource exploitation.

Intergenerational Justice

Intergenerational justice is the idea that current generations have moral obligations to future generations regarding the environment. It asks us to consider the long-term impacts of our actions and ensure that future generations inherit a planet capable of sustaining their well-being.

This concept is particularly relevant to issues like climate change, where the emissions of today will have profound consequences for people living decades or centuries from now. It compels us to think beyond immediate gratification and consider the legacy we leave behind.

The Precautionary Principle

The precautionary principle suggests that when an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. In simpler terms, “better safe than sorry.”

- Application: If there is a strong suspicion that a new chemical or technology could harm the environment, even without absolute scientific proof, the precautionary principle advises against its widespread use until its safety is confirmed.

Sustainability

Sustainability is a core concept, often defined as meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It integrates environmental protection with social equity and economic viability, aiming for a long-term balance.

- Pillars of Sustainability:

- Environmental: Protecting natural resources and ecosystems.

- Social: Ensuring human well-being, equity, and justice.

- Economic: Fostering viable economic systems that support human needs without depleting resources.

Achieving sustainability requires ethical choices that balance competing demands and prioritize long-term planetary health.

Applications of Environmental Ethics in the Real World

Environmental ethics is not just theoretical; it provides the moral compass for navigating real-world environmental dilemmas and shaping policy.

Climate Change

The climate crisis presents one of the most significant ethical challenges. It involves questions of:

- Responsibility: Who is most responsible for historical emissions, and who should bear the burden of mitigation?

- Equity: How do the impacts of climate change disproportionately affect vulnerable communities and developing nations?

- Intergenerational Justice: What do we owe to future generations who will inherit a changed planet?

Ethical frameworks help us argue for urgent action, fair burden-sharing, and support for those most affected.

Biodiversity Loss

The accelerating extinction rate of species raises profound ethical questions:

- Do species have a right to exist independent of human utility (biocentrism)?

- What is our moral obligation to protect the intricate web of life that forms healthy ecosystems (ecocentrism)?

- What are the long-term consequences for human well-being if biodiversity collapses (anthropocentrism)?

Environmental ethics underpins arguments for habitat preservation, anti-poaching efforts, and sustainable land use.

Pollution and Waste Management

From plastic pollution in oceans to toxic waste in landfills, human activities generate vast amounts of waste. Ethical considerations include:

- The right to a clean environment for all people (environmental justice).

- Our responsibility to minimize harm to non-human life and ecosystems.

- The moral imperative to develop circular economies and reduce consumption.

Resource Management and Conservation

Decisions about how we use water, forests, minerals, and energy are deeply ethical. Should we prioritize immediate economic gain or long-term ecological health? Should we exploit every available resource or leave some untouched for their intrinsic value or for future generations?

“A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

— Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

This famous quote from Aldo Leopold’s “Land Ethic” encapsulates an ecocentric approach to resource management, urging us to consider the health of the entire ecosystem.

Challenges and Debates in Environmental Ethics

While environmental ethics provides crucial guidance, it is not without its complexities and internal debates.

Balancing Competing Values

Often, environmental protection must be balanced against other legitimate human needs, such as economic development, poverty alleviation, or national security. Finding ethical solutions requires careful consideration and compromise.

Defining “Nature” and “Wilderness”

What exactly are we trying to protect? Is it pristine wilderness untouched by humans, or can human-modified landscapes also hold environmental value? The definition of “natural” itself can be a point of contention.

Cultural and Global Perspectives

Environmental values and priorities can vary significantly across different cultures and regions of the world. What is considered ethical in one society might not be in another, leading to challenges in global environmental governance.

The Problem of Future Generations

While intergenerational justice is a powerful concept, precisely defining our obligations to people who do not yet exist, and who may have different needs and values, presents philosophical difficulties.

Moving Forward: The Enduring Relevance of Environmental Ethics

Environmental ethics offers more than just a set of rules; it provides a way of thinking that encourages us to broaden our moral horizons. It challenges us to move beyond narrow self-interest and consider the well-being of the entire planet and all its inhabitants, both present and future.

As the ecological crises of the 21st century intensify, the insights provided by environmental ethics become increasingly critical. It empowers individuals, communities, and policymakers to make more informed, responsible, and compassionate decisions. By embracing these ethical principles, humanity can strive towards a future where both human flourishing and ecological integrity are not just aspirations, but realities.