In an increasingly interconnected world, the choices made in our own backyards hold profound significance for the planet’s health. One such choice, native plant gardening, transcends mere aesthetics to become a powerful act of ecological restoration. This practice involves cultivating plants that are indigenous to a specific region, fostering a vibrant ecosystem that thrives in harmony with local wildlife and natural processes. Far from being a niche hobby, native plant gardening is a vital strategy for supporting biodiversity, conserving resources, and reconnecting with the natural world.

What Are Native Plants? Understanding Their Roots

At its core, a native plant is a species that has evolved naturally in a particular region over thousands of years, without human introduction. These plants have adapted to the local climate, soil conditions, and rainfall patterns, forming intricate relationships with the native insects, birds, and other wildlife that depend on them for survival. Their presence is a cornerstone of the local food web and ecosystem stability.

The concept of “native” is inherently geographical. A plant considered native to the prairies of North America, for instance, would be an exotic species in a European forest. This regional specificity is crucial because it dictates the plant’s ecological role and its ability to support local fauna. Native plants are not just survivors; they are integral components of a complex, interdependent natural community.

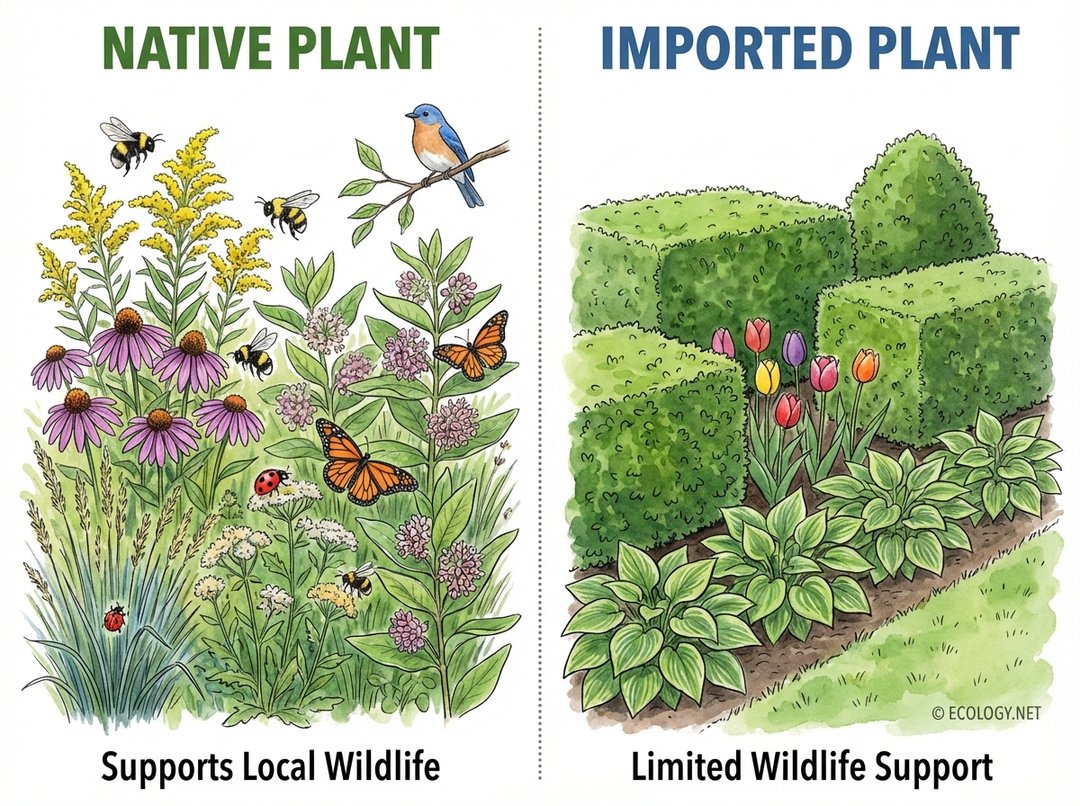

Conversely, imported or non-native plants, often called “exotics” or “ornamentals,” are species introduced from other parts of the world. While many are harmless and beautiful, some can become invasive, outcompeting native flora, disrupting ecosystems, and offering little to no ecological benefit to local wildlife. The distinction is not merely academic; it has tangible consequences for the health of our environment.

Why Choose Native Plants? The Ecological Imperative

The benefits of native plant gardening extend far beyond a pretty landscape. They represent a fundamental shift towards a more sustainable and ecologically responsible approach to land stewardship.

Supporting Biodiversity and Local Wildlife

Native plants are the foundation of local food webs. They provide essential food sources, such as nectar, pollen, seeds, and host leaves, for native insects, including crucial pollinators like bees and butterflies. These insects, in turn, become food for birds, amphibians, and other animals. Without native plants, many local wildlife populations struggle to survive.

- Pollinator Powerhouses: Many native flowers have co-evolved with specific native pollinators, offering precisely the right shape, color, and nectar composition to attract them. This specialized relationship is vital for the survival of both the plant and the pollinator.

- Caterpillar Cafeterias: A significant number of insect species, particularly butterflies and moths, can only lay their eggs and feed their larvae on specific native host plants. For example, monarch butterfly caterpillars exclusively feed on milkweed species. Without these host plants, the entire life cycle of such insects is broken.

- Shelter and Nesting Sites: The varied structures of native trees, shrubs, and grasses provide critical shelter, nesting materials, and safe havens for birds, small mammals, and beneficial insects.

Water Conservation and Soil Health

Having adapted to local rainfall patterns, native plants typically require less supplemental watering once established, making them excellent choices for water-wise landscaping. Their deep root systems also play a crucial role in soil health.

- Reduced Irrigation: Native plants are naturally drought-tolerant in their native range, significantly reducing the need for irrigation, especially during dry periods.

- Erosion Control: The extensive root systems of native grasses and wildflowers help stabilize soil, prevent erosion, and improve water infiltration, reducing stormwater runoff.

- Improved Soil Structure: These deep roots also contribute to healthy soil structure, increasing organic matter and fostering a thriving underground microbial community.

Reduced Maintenance and Resilience

Once established, native gardens often require less intervention than traditional ornamental gardens.

- Natural Pest Resistance: Native plants have evolved defenses against local pests and diseases, reducing the need for chemical pesticides.

- Adaptability: Their inherent adaptation to local conditions means they are more resilient to extreme weather events, temperature fluctuations, and typical soil types, requiring less fertilization and amendment.

- Less Mowing: Replacing turf grass with native plant beds can drastically reduce the amount of lawn mowing, saving time, fuel, and reducing air pollution.

Getting Started with Native Plant Gardening: A Beginner’s Guide

Embarking on a native plant gardening journey is an exciting and rewarding endeavor. Here are the foundational steps to begin transforming your space into a thriving ecological haven.

Research Your Local Ecosystem

The first and most critical step is to understand what is native to your specific region. “Native” is not a broad brushstroke; it is highly localized.

- Consult Local Resources: Reach out to local native plant societies, university extension offices, botanical gardens, nature centers, or even knowledgeable staff at reputable nurseries.

- Utilize Online Databases: Websites dedicated to native plants often allow you to search by zip code or region to generate lists of appropriate species.

- Observe Your Surroundings: Pay attention to what grows naturally in nearby undeveloped areas, parks, or nature preserves.

Assess Your Site Conditions

Just like any gardening project, understanding your site’s unique characteristics is key to selecting the right plants.

- Sunlight: Map out how much sun different areas of your garden receive throughout the day (full sun, partial sun, shade).

- Soil Type: Determine if your soil is sandy, loamy, or clayey. You can do a simple jar test or send a sample for professional analysis.

- Moisture Levels: Observe how well your soil drains. Is it consistently wet, moist, or very dry?

Plan Your Garden Design

Even a small native garden can make a big impact. Start small and expand as you gain confidence.

- Start Small: Consider converting a small section of your lawn or an existing flower bed.

- Think in Layers: Incorporate plants of varying heights and forms to create visual interest and diverse habitats.

- Consider Bloom Times: Choose plants that offer continuous blooms from spring through fall to provide a consistent food source for pollinators.

- Group Similar Needs: Place plants with similar sun, soil, and water requirements together.

Plant Selection Examples for Beginners

Many native plants are remarkably forgiving and beautiful. Here are a few examples that are often good starting points, but always verify their native status for your specific region:

- For Sunny Areas:

- Coneflowers (Echinacea spp.)

- Black-eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta)

- Milkweed (Asclepias spp.)

- Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

- Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

- For Shady Areas:

- Ferns (e.g., Lady Fern, Maidenhair Fern)

- Wild Ginger (Asarum canadense)

- Foamflower (Tiarella cordifolia)

- Hostas (though many are non-native, some native alternatives exist)

Planting and Initial Care

Planting native plants is similar to planting any other perennial. Dig a hole twice as wide as the root ball, place the plant at the same depth it was in its container, backfill with soil, and water thoroughly. During the first year, consistent watering is crucial to help plants establish their deep root systems. Once established, they will typically require minimal intervention.

Advanced Concepts: Elevating Your Native Garden

For those ready to delve deeper, native plant gardening offers sophisticated strategies to maximize ecological impact and create truly resilient landscapes.

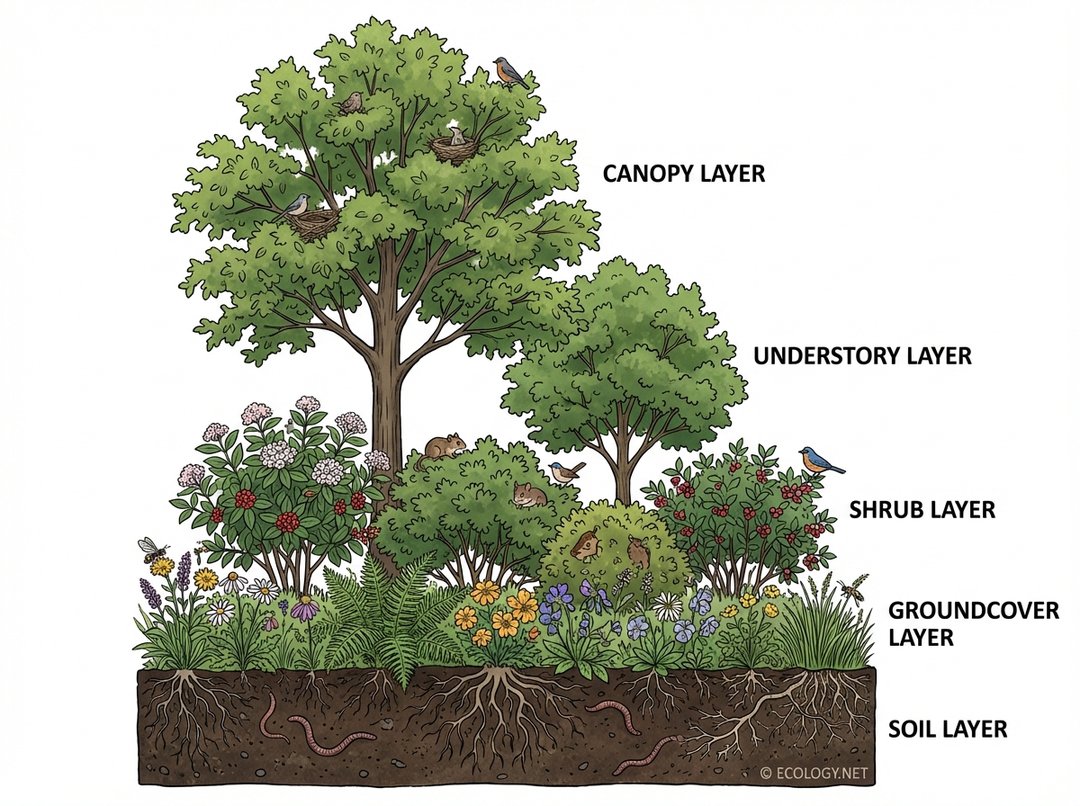

Creating Habitat Layers

A truly biodiverse garden mimics natural ecosystems by providing multiple vertical layers of vegetation. This stratification offers diverse microclimates, food sources, and shelter for a wider array of wildlife, from ground-dwelling insects to canopy-nesting birds.

- Canopy Layer: Tall native trees (e.g., oaks, maples, hickories) provide shade, nesting sites for birds, and host plants for numerous insect species.

- Understory Layer: Smaller native trees or large shrubs (e.g., serviceberry, redbud, dogwood) offer additional nesting, fruit, and nectar sources.

- Shrub Layer: Medium-sized native shrubs (e.g., viburnums, elderberry, native azaleas) provide dense cover, berries, and flowers.

- Perennial/Groundcover Layer: A diverse mix of native wildflowers, grasses, and ferns creates a rich tapestry of food and shelter for insects, small mammals, and ground-nesting birds.

- Soil Layer: Healthy soil, teeming with microorganisms and fungi, is the often-overlooked foundation of the entire ecosystem, supported by the deep roots of native plants.

Understanding Keystone Species

Some native plant species are disproportionately important to the health of an ecosystem. These are known as keystone species. For example, oak trees (Quercus spp.) can host hundreds of species of moth and butterfly caterpillars, providing a massive food source for birds. Planting keystone species can have an outsized positive impact on local biodiversity.

Designing for Succession and Dynamic Ecosystems

Natural ecosystems are not static; they evolve over time. A native garden can be designed to embrace this dynamism, allowing for natural plant succession and self-seeding. This approach fosters a more resilient and less labor-intensive garden that adapts to changing conditions.

Implementing Rain Gardens and Bioswales

For areas prone to stormwater runoff, incorporating rain gardens or bioswales planted with native species can be highly effective. These features are designed to capture and filter rainwater, reducing pollution and recharging groundwater, while simultaneously creating unique wetland or moist-soil habitats.

Community Involvement and Advocacy

Beyond individual gardens, advocating for native plant use in public spaces, schools, and community projects amplifies the impact. Participating in local native plant initiatives or educating neighbors can foster a broader movement towards ecological landscaping.

Common Misconceptions and Challenges

Despite their numerous benefits, native plant gardening sometimes faces misconceptions.

- “Native plants are messy or wild-looking.” While some native plants have a more naturalistic growth habit, thoughtful design can create stunning, manicured native gardens that are both beautiful and ecologically functional.

- “They don’t look as good as traditional ornamentals.” This is a matter of perspective. Native plants offer a unique, authentic beauty that changes with the seasons, providing vibrant blooms, interesting textures, and the added delight of abundant wildlife.

- Sourcing challenges. Finding truly local native plants can sometimes be difficult. Seek out reputable nurseries that specialize in native species and avoid plants treated with systemic pesticides that could harm pollinators.

- Patience is key. Native plants, especially those establishing deep root systems, may take a year or two to fully establish and show their full potential. The long-term rewards, however, are well worth the initial patience.

Conclusion

Native plant gardening is more than a trend; it is a powerful, accessible solution to many pressing environmental challenges. By choosing to cultivate plants that belong in our landscapes, we actively participate in restoring ecological balance, supporting vital wildlife, conserving precious resources, and fostering a deeper connection to the natural world. Every native plant planted is a step towards a healthier, more vibrant planet, transforming our personal spaces into essential havens for biodiversity. Embrace the beauty and power of native plants, and watch your garden come alive with purpose.