The Earth, often called the “Blue Planet,” owes its distinctive hue to the vast, interconnected body of saltwater that covers over 70% of its surface: the ocean. Far more than just a massive reservoir, the ocean is a dynamic, living system that shapes our climate, sustains countless species, and holds mysteries yet to be fully uncovered. From the sunlit surface to the crushing pressures of the deepest trenches, the ocean is a realm of incredible diversity and profound ecological significance.

The Abiotic Realm: Foundations of Ocean Life

Life in the ocean is fundamentally governed by its physical and chemical properties. These abiotic factors create distinct environments, dictating where and how organisms can thrive.

Light and Temperature: The Vertical Divide

Perhaps the most critical abiotic factor is sunlight. Water absorbs light, meaning that sunlight penetrates only a limited distance into the ocean. This creates two primary vertical zones:

- The Photic Zone: Also known as the euphotic zone, this is the uppermost layer where sunlight is sufficient for photosynthesis. Its depth varies greatly depending on water clarity, from a few meters in turbid coastal waters to over 200 meters in the clear open ocean. This is where most marine primary production occurs.

- The Aphotic Zone: Below the photic zone, light levels are too low for photosynthesis. This vast, dark realm extends to the seafloor, characterized by perpetual twilight or complete darkness. Life here relies on food sinking from above or on chemosynthesis.

Temperature also stratifies the ocean. Surface waters, warmed by the sun, are generally warmer and less dense. As depth increases, temperature typically drops, often quite rapidly across a boundary called the thermocline, leading to the cold, stable conditions of the deep ocean.

This vertical stratification of light and temperature is a foundational concept for understanding ocean ecosystems. For instance, the warm, sunlit photic zone is a bustling hub of photosynthetic activity, while the cold, dark aphotic zone presents unique challenges and opportunities for adaptation.

Salinity, Pressure, and Currents

Ocean water is saline, with an average salinity of about 3.5%, meaning 35 grams of dissolved salts per kilogram of water. This salinity influences water density, freezing point, and the physiological processes of marine organisms.

Pressure is another formidable factor. For every 10 meters of depth, pressure increases by approximately one atmosphere. Organisms living in the deep sea have evolved remarkable adaptations to withstand immense pressures that would crush surface dwellers.

Ocean currents, driven by wind, temperature, salinity, and the Earth’s rotation, act as global conveyor belts. They distribute heat from the equator to the poles, transport nutrients, and disperse marine larvae, profoundly influencing climate and the distribution of marine life.

The Biotic Realm: Life in the Blue

The sheer volume and diversity of ocean habitats support an astonishing array of life, from microscopic bacteria to the largest animal on Earth, the blue whale.

Producers, Consumers, and Decomposers: The Marine Food Web

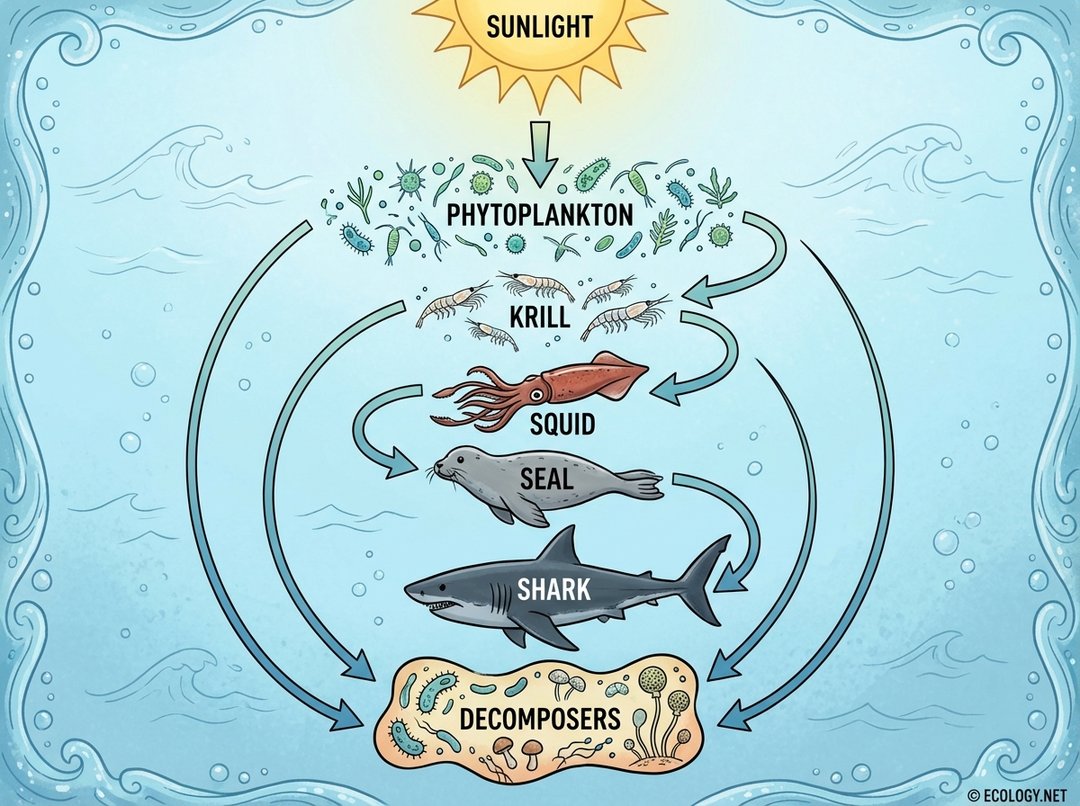

Like all ecosystems, marine life is organized into trophic levels, illustrating the flow of energy from producers to consumers and ultimately to decomposers.

- Primary Producers: The base of most marine food webs consists of phytoplankton, microscopic photosynthetic organisms that drift in the photic zone. They convert sunlight into organic matter, much like plants on land. In certain deep-sea environments, chemosynthetic bacteria form the base, utilizing chemical energy instead of light.

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): Zooplankton, tiny animals that graze on phytoplankton, are the primary consumers. Examples include copepods and krill, which are crucial food sources for larger animals.

- Secondary and Tertiary Consumers (Carnivores): These include a vast range of organisms, from small fish and squid to larger predators like seals, dolphins, and sharks. Each level consumes the one below it, transferring energy up the food chain.

- Decomposers: Bacteria and fungi play a vital role in breaking down dead organic matter from all trophic levels, returning essential nutrients to the water column, which can then be utilized by primary producers. This recycling process is fundamental to the ocean’s productivity.

The intricate dance of predator and prey, fueled by the sun’s energy or chemical reactions, forms the complex tapestry of marine life. A disruption at any level can have cascading effects throughout the entire ecosystem.

Major Ocean Ecosystems

The ocean encompasses a variety of distinct ecosystems, each with its own unique characteristics and inhabitants.

- Coastal Zones: These highly productive areas include estuaries, salt marshes, mangrove forests, and coral reefs. They are characterized by fluctuating conditions (tides, salinity) and high biodiversity. Coral reefs, for example, are often called the “rainforests of the sea” due to their immense species richness.

- Open Ocean (Pelagic Zone): This vast expanse of water away from the coast is divided into several sub-zones based on depth. The epipelagic zone (surface waters) is home to plankton, nekton (free-swimming animals like fish and whales), and marine birds. Deeper pelagic zones are characterized by darkness and specialized adaptations.

- Deep Sea (Benthic Zone): This refers to the ocean floor, from the continental shelf to the abyssal plains and deep-sea trenches. Life here is often sparse but highly specialized, adapted to cold temperatures, immense pressure, and lack of light.

Deep Sea Hydrothermal Vents: Oases in the Abyss

Among the most extraordinary deep-sea ecosystems are hydrothermal vents. These geological features occur along mid-ocean ridges where tectonic plates pull apart, allowing seawater to seep into the Earth’s crust and become superheated by magma. The hot, mineral-rich water then erupts back into the ocean, forming towering “chimneys.”

Life around these vents is entirely independent of sunlight. Instead, chemosynthetic bacteria form the base of the food web, converting hydrogen sulfide and other chemicals from the vent fluids into organic matter. This supports a unique community of organisms, including giant tube worms, specialized clams, mussels, and crabs, many of which are found nowhere else on Earth. These ecosystems are profound examples of life thriving in extreme conditions, challenging our understanding of where life can exist.

Oceanic Processes and Global Cycles

The ocean is not static; it is a constantly moving and interacting system that plays a critical role in global biogeochemical cycles.

Ocean Currents and Circulation

Beyond surface currents, a global “thermohaline circulation” or “ocean conveyor belt” moves vast quantities of water around the planet. This circulation is driven by differences in temperature (thermo) and salinity (haline), which affect water density. Cold, salty water sinks in polar regions and flows along the deep ocean floor, eventually rising in other parts of the world. This process is crucial for distributing heat, oxygen, and nutrients globally.

The Ocean’s Role in the Carbon Cycle

The ocean is the largest active carbon sink on Earth, absorbing a significant portion of the carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This occurs through two main mechanisms:

- The Solubility Pump: CO2 dissolves directly into seawater. Colder water can hold more dissolved gas.

- The Biological Pump: Phytoplankton absorb CO2 during photosynthesis. When these organisms die or are consumed, carbon can sink to the deep ocean as organic matter, effectively sequestering it for long periods.

This immense capacity to absorb carbon dioxide makes the ocean a critical regulator of Earth’s climate.

Challenges and Conservation

Despite its vastness and resilience, the ocean faces unprecedented threats from human activities.

- Pollution: Plastic pollution, chemical runoff from land, and oil spills degrade marine habitats and harm wildlife. Microplastics, in particular, are pervasive, entering the food web and impacting organisms from plankton to whales.

- Overfishing: Unsustainable fishing practices have depleted fish stocks globally, disrupting marine food webs and threatening the livelihoods of coastal communities. Bycatch, the accidental capture of non-target species, further exacerbates the problem.

- Climate Change Impacts:

- Ocean Warming: Rising ocean temperatures lead to coral bleaching, alter species distribution, and contribute to sea-level rise.

- Ocean Acidification: As the ocean absorbs more CO2, its pH decreases, making it more acidic. This impacts marine organisms that build shells or skeletons from calcium carbonate, such as corals, shellfish, and some plankton, making it harder for them to grow and survive.

- Deoxygenation: Warmer waters hold less dissolved oxygen, and altered circulation patterns can lead to “dead zones” where oxygen levels are too low to support most marine life.

Protecting the ocean requires a multifaceted approach, including reducing pollution, implementing sustainable fishing practices, establishing marine protected areas, and mitigating climate change through global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Conclusion

The ocean is a realm of profound beauty, immense power, and vital importance to all life on Earth. From its sunlit surface teeming with photosynthetic life to the mysterious depths where chemosynthetic communities thrive, it is a testament to the adaptability and diversity of nature. Understanding its complex systems, appreciating its intricate food webs, and recognizing the critical role it plays in regulating our planet’s climate are essential. As stewards of this magnificent blue world, humanity bears the responsibility to protect its health and ensure its continued vitality for generations to come.