The Aquatic Apex: Unraveling the World of Piscivores

The intricate dance of life in aquatic ecosystems is a captivating spectacle, a constant interplay of predator and prey. At the heart of many of these watery worlds stand the piscivores, a diverse and fascinating group of animals whose very existence revolves around the pursuit and consumption of fish. From the swift dive of an osprey to the silent ambush of a pike, these creatures are not just hunters; they are architects of their environments, shaping food webs and influencing the health of entire aquatic habitats. Understanding piscivores is key to unlocking the secrets of ecological balance and appreciating the incredible adaptations forged in the crucible of evolution.

Who are the Piscivores? A Global Gallery of Fish Eaters

At its core, a piscivore is any animal that primarily feeds on fish. This dietary specialization has led to an astonishing array of adaptations across the animal kingdom, demonstrating nature’s ingenuity in exploiting a rich and abundant food source. Piscivores can be found in virtually every aquatic environment, from the deepest oceans to the smallest freshwater streams.

Let us explore some prominent examples:

- Birds: Many avian species have mastered the art of fishing.

- Ospreys: Renowned for their dramatic dives, snatching fish with specialized talons.

- Kingfishers: Small, colorful birds that plunge headfirst into water.

- Pelicans: Use their massive gular pouches to scoop up fish.

- Herons and Egrets: Stalk prey in shallow waters with long legs and sharp beaks.

- Cormorants: Dive and pursue fish underwater with powerful webbed feet.

- Mammals: A diverse group, from marine giants to agile river dwellers.

- Seals and Sea Lions: Pinnipeds that are expert underwater hunters.

- Dolphins and Porpoises: Marine mammals that use echolocation to find schooling fish.

- Otters: Playful and agile predators of freshwater and coastal areas.

- Polar Bears: While primarily seal eaters, they will also hunt fish, especially during lean times.

- Reptiles: Ancient predators with formidable fishing skills.

- Crocodiles and Alligators: Ambush predators that snatch fish from the water’s edge.

- Sea Snakes: Highly venomous marine reptiles that hunt fish in coral reefs and open ocean.

- Some Freshwater Snakes: Certain species, like the Northern Water Snake, are adept at catching fish.

- Fish: Many fish species themselves are piscivores, creating complex intra-species food webs.

- Pike: A classic ambush predator of freshwater, known for its torpedo-like strikes.

- Bass: Popular game fish that prey on smaller fish.

- Sharks: Apex predators of the ocean, with many species specializing in fish.

- Barracuda: Swift, solitary hunters with razor-sharp teeth.

- Tuna: Fast-swimming oceanic predators that hunt schooling fish.

- Amphibians: While less common, some amphibians are also piscivorous.

- Giant Salamanders: Large aquatic amphibians that prey on fish.

- Some Frogs: Larger frog species may occasionally consume small fish.

The Pivotal Role of Piscivores in Ecosystems

Piscivores are far more than just hungry mouths; they are critical components of aquatic ecosystems, playing a vital role in maintaining balance and health. Their position at higher trophic levels means their presence or absence can send ripples throughout the entire food web.

Food Web Dynamics and Population Control

As apex or near-apex predators, piscivores exert significant top-down control on the populations of their prey fish. Without these predators, prey fish populations can explode, leading to overgrazing of their own food sources, which are often smaller invertebrates or algae. This regulation helps prevent any single species from dominating and ensures a healthier, more diverse ecosystem. For example, a healthy population of large mouth bass can keep panfish populations in check, preventing them from overconsuming zooplankton and aquatic insects.

Indicators of Ecosystem Health

The presence of a robust piscivore population often signals a healthy aquatic environment. These animals typically require clean water, abundant prey, and intact habitats to thrive. A decline in piscivore numbers can therefore serve as an early warning sign of environmental degradation, such as pollution, habitat loss, or overfishing.

The Ripple Effect: Understanding Trophic Cascades

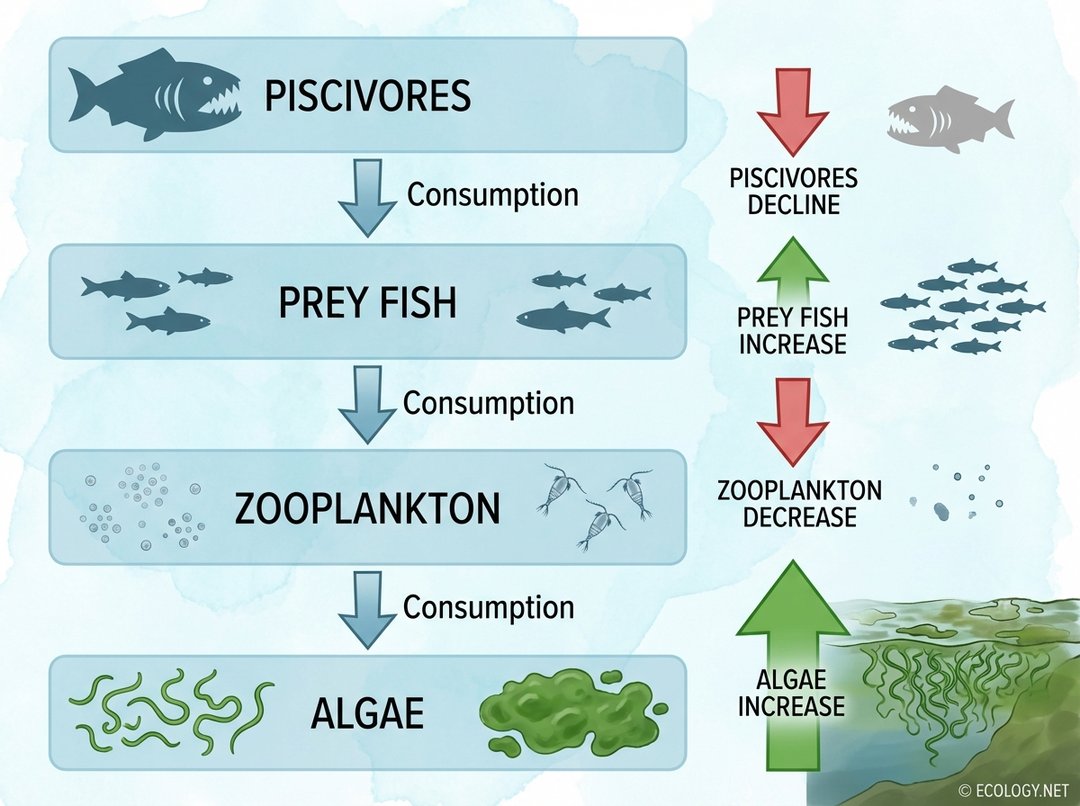

One of the most profound impacts of piscivores is their ability to trigger what ecologists call a trophic cascade. This is a powerful indirect interaction where a predator at the top of the food chain influences the abundance of species at multiple lower trophic levels.

Consider a classic example in a freshwater lake:

- Piscivores Decline: If the population of large piscivores, such as pike or large bass, decreases due to factors like overfishing or pollution.

- Prey Fish Increase: With fewer predators, the populations of smaller, plankton-eating fish (like minnows or juvenile perch) can rapidly increase.

- Zooplankton Decrease: These abundant prey fish then consume vast quantities of zooplankton, tiny aquatic invertebrates that graze on algae.

- Algae Increase: With fewer zooplankton to control them, algal populations can explode, leading to algal blooms. These blooms can reduce water clarity, deplete oxygen, and harm other aquatic life.

This demonstrates how a change at the very top of the food web can have dramatic, cascading effects all the way down to the primary producers, fundamentally altering the ecosystem’s structure and function.

Ingenious Adaptations for a Fishy Diet

The specialized diet of piscivores has driven the evolution of remarkable physical and behavioral adaptations, allowing them to efficiently locate, capture, and consume their slippery prey.

Physical Adaptations

- Specialized Jaws and Teeth: Many piscivores possess long, conical, or needle-sharp teeth designed for gripping and holding struggling fish. Examples include the interlocking teeth of a barracuda, the backward-pointing teeth of a pike, or the serrated edges of a shark’s teeth.

- Streamlined Bodies: Aquatic piscivores like dolphins, tuna, and barracuda have sleek, hydrodynamic bodies that allow for rapid pursuit through water.

- Powerful Talons and Beaks: Fish-eating birds like ospreys have large, curved talons with barbed pads to secure fish, while pelicans have massive pouches to scoop them up. Herons and kingfishers boast sharp, dagger-like beaks for spearing.

- Sensory Organs: Keen eyesight is crucial for many, such as the sharp vision of an osprey. Dolphins use echolocation to navigate and locate fish schools in murky waters. Some fish, like sharks, have an acute sense of smell and can detect electrical fields generated by prey.

Behavioral Adaptations

- Hunting Strategies:

- Ambush: Pike and crocodiles lie in wait, striking with explosive speed when prey comes close.

- Pursuit: Tuna and dolphins actively chase down schools of fish.

- Stalking: Herons slowly wade through shallow water, patiently waiting for the opportune moment.

- Cooperative Hunting: Some marine mammals, like dolphins, work together to herd fish into tight balls, making them easier to catch.

- Camouflage: Many piscivores, especially those that ambush, possess cryptic coloration that helps them blend into their aquatic surroundings, making them invisible to unsuspecting prey.

Studying Piscivores: Unraveling Their Secrets

Understanding the dietary habits and ecological roles of piscivores is crucial for effective conservation and ecosystem management. Scientists employ a variety of methods, ranging from traditional observations to cutting-edge analytical techniques.

Traditional Methods

- Direct Observation: Watching piscivores hunt can provide valuable insights into their preferred prey and hunting strategies. However, many piscivores are elusive or hunt underwater, making this challenging.

- Stomach Content Analysis: Examining the stomach contents of captured or deceased piscivores directly reveals what they have recently eaten. While precise, this method only shows a snapshot of their diet and requires invasive procedures or deceased specimens.

Advanced Techniques

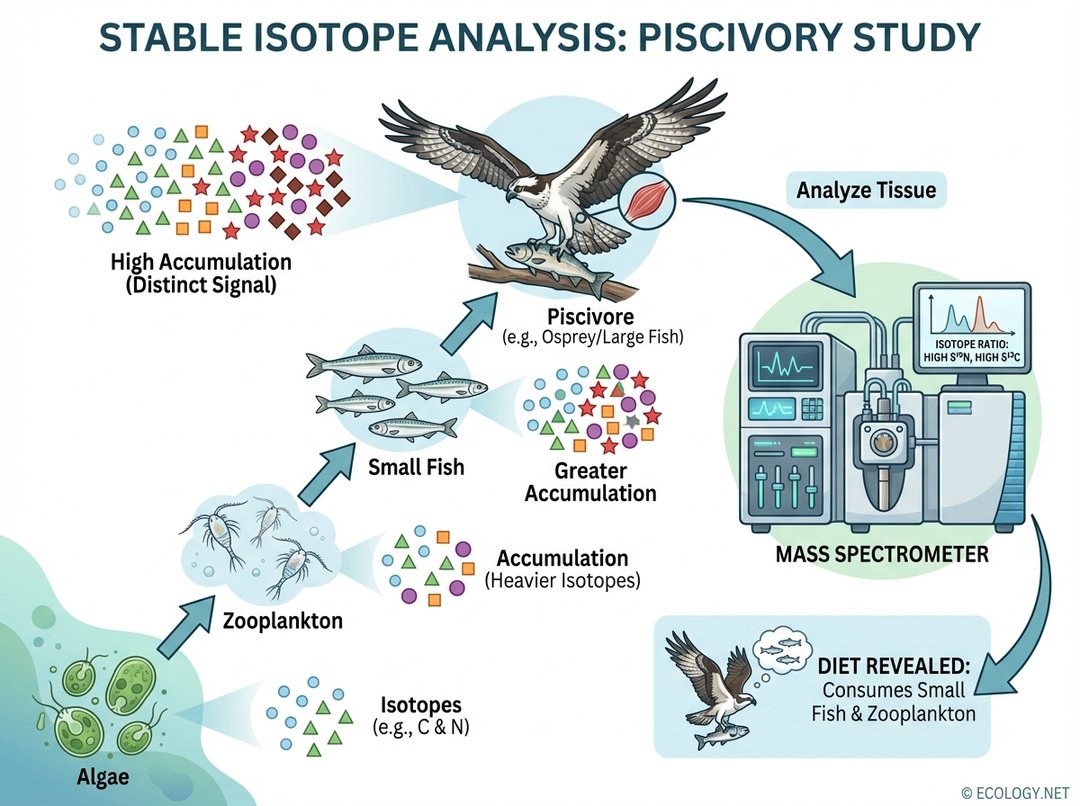

- Stable Isotope Analysis: This powerful technique allows scientists to determine a piscivore’s diet over a longer period, not just its last meal.

How it works:

- Organisms incorporate stable isotopes (non-radioactive variants of elements like carbon and nitrogen) from their diet into their tissues.

- As these isotopes move up the food chain, they become progressively enriched in the predator’s tissues in predictable ways.

- By analyzing the isotopic ratios in a piscivore’s tissue (e.g., muscle, scales, feathers), researchers can infer the types of prey it has consumed and even the ecosystem from which the prey originated. This provides a long-term dietary signature.

- Genetic Analysis (eDNA and Gut Content DNA): Environmental DNA (eDNA) can be collected from water samples to detect the presence of prey species. Analyzing DNA fragments from a piscivore’s gut contents or feces can identify the exact species it has consumed, offering a non-invasive alternative to stomach content analysis.

- Telemetry and Tagging: Attaching tracking devices to piscivores allows researchers to monitor their movements, habitat use, and interactions with prey, providing insights into their foraging ecology and spatial distribution.

Conservation Challenges and the Importance of Protection

Despite their ecological importance, piscivores worldwide face numerous threats, many of which are human-induced.

- Habitat Loss and Degradation: Wetlands draining, river damming, coastal development, and pollution all destroy critical habitats for both piscivores and their prey.

- Overfishing: Direct overfishing of piscivore species can decimate their populations. Additionally, overfishing of their prey species can lead to food scarcity, impacting piscivore survival and reproduction.

- Pollution: Accumulation of toxins like mercury and PCBs in fish can bioaccumulate up the food chain, reaching dangerous levels in piscivores, affecting their health, reproduction, and survival.

- Climate Change: Changes in water temperature, ocean acidification, and altered precipitation patterns can disrupt aquatic ecosystems, impacting fish populations and, consequently, their predators.

Protecting piscivores is not merely about saving a single species; it is about safeguarding the health and resilience of entire aquatic ecosystems. Their conservation ensures the continuation of vital ecological processes, maintains biodiversity, and provides a clear indicator of environmental quality.

Conclusion: Appreciating the Guardians of the Water

Piscivores, in all their diverse forms, are truly the guardians of our aquatic realms. From the smallest fish-eating insect to the largest oceanic shark, these predators play an indispensable role in shaping the natural world. They control populations, drive trophic cascades, and serve as sentinels of environmental health. By understanding their intricate lives, their adaptations, and the challenges they face, we gain a deeper appreciation for the delicate balance of nature and our own responsibility in preserving these magnificent and vital creatures for generations to come.