Imagine a vibrant, bustling strip of green that hugs the edges of every river, stream, and lake. This isn’t just any patch of land; it is a dynamic, life-sustaining ecosystem known as a riparian zone. Often overlooked, these narrow corridors are among the most critical and biodiverse habitats on Earth, acting as nature’s vital link between aquatic and terrestrial environments. Understanding and appreciating riparian zones is key to safeguarding the health of our planet’s waterways and the countless species that depend on them.

What Exactly Is a Riparian Zone?

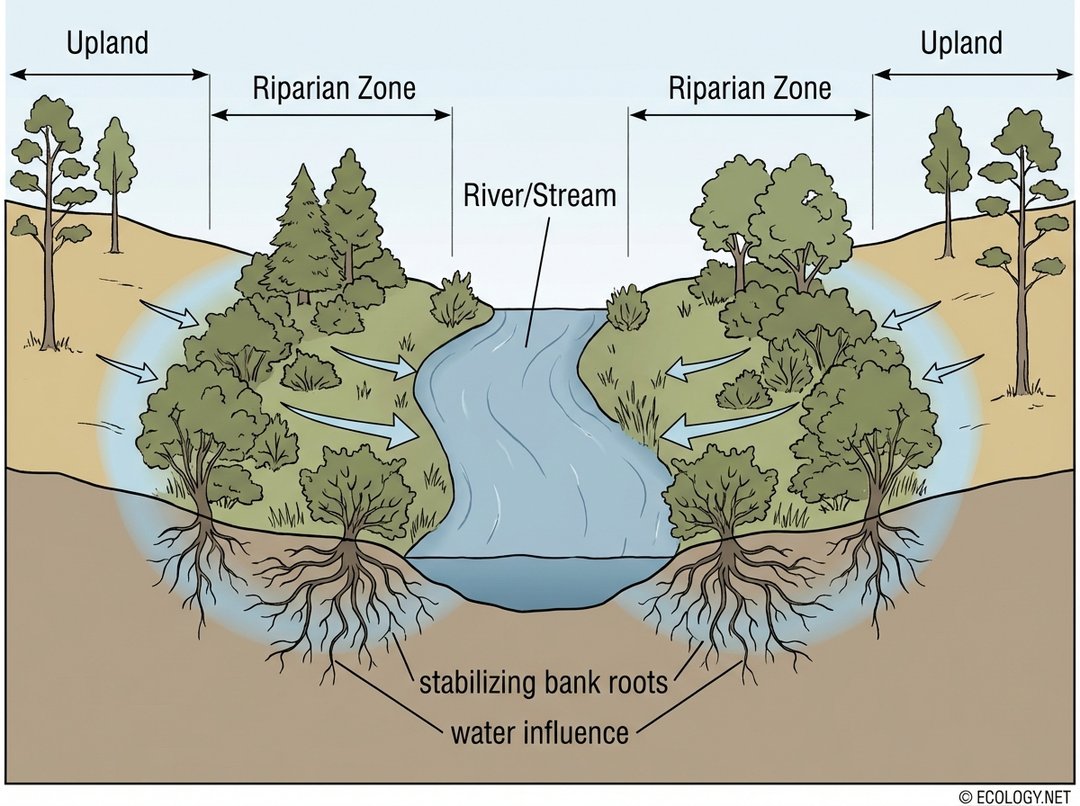

At its core, a riparian zone is the interface between land and a river or stream. The term “riparian” itself comes from the Latin word “ripa,” meaning riverbank. It is not merely the immediate bank but a broader area whose vegetation and soil are directly influenced by the presence of water. This influence manifests in higher soil moisture, unique plant communities adapted to these conditions, and a distinct microclimate.

Think of it as a transitional buffer. On one side, you have the flowing water of the river or stream. On the other, you have the drier, more typical upland environment. The riparian zone sits squarely in between, sharing characteristics of both. Its boundaries are not always sharply defined but are typically marked by changes in plant species, soil composition, and water table depth. For instance, you might find water-loving willows and cottonwoods thriving in the riparian zone, while oaks and pines dominate the adjacent uplands.

The extent of a riparian zone can vary dramatically. In arid regions, it might be a narrow ribbon of green in an otherwise dry landscape, often referred to as a “green line.” In more humid areas, it can stretch for many meters, encompassing floodplains and wetlands that are regularly inundated. Regardless of its size, the defining characteristic remains the strong ecological connection to the water body it borders.

Why Are Riparian Zones So Important?

The ecological services provided by healthy riparian zones are immense and far-reaching, impacting everything from water quality to wildlife populations. These areas are truly multi-tasking marvels of nature.

Water Quality Guardians

Perhaps one of the most critical functions of a riparian zone is its role in maintaining and improving water quality. The dense vegetation acts as a natural filter, intercepting runoff from agricultural fields, urban areas, and other landscapes before it reaches the river. This filtration process removes:

- Sediment: Soil particles carried by runoff are trapped by vegetation, preventing them from clouding the water and smothering aquatic habitats.

- Nutrients: Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers are absorbed by riparian plants, preventing harmful algal blooms in the water body.

- Pollutants: Various chemicals, pesticides, and heavy metals can be taken up by plants or broken down by soil microbes within the riparian zone.

By effectively cleaning the water, riparian zones ensure healthier aquatic ecosystems downstream and safer drinking water sources for human communities.

Erosion Control and Bank Stabilization

The extensive root systems of riparian plants are nature’s rebar for riverbanks. These roots bind the soil together, creating a strong, stable structure that resists the erosive forces of flowing water. Without this natural armor, riverbanks become vulnerable to collapse, especially during floods. Eroded banks contribute massive amounts of sediment to the water, degrading habitat and altering river channels. A healthy riparian zone, with its interwoven network of roots, significantly reduces bank erosion, maintaining the integrity of the river system.

Biodiversity Hotspots

Riparian zones are magnets for biodiversity. The unique combination of water, varied vegetation, and diverse microclimates creates a rich tapestry of habitats that support an incredible array of life. They serve as:

- Wildlife corridors: Many animals, from deer to small mammals, use riparian zones as natural pathways for movement, especially in fragmented landscapes.

- Breeding and nesting grounds: Birds, amphibians, and insects find ideal conditions for reproduction and raising their young.

- Food sources: The abundance of insects, plants, and aquatic life provides a rich food web for countless species.

For example, a single riparian forest might host dozens of bird species, provide critical spawning grounds for fish, and offer refuge for amphibians and reptiles, all within a relatively small area.

Climate Regulation and Shade

The trees and shrubs in a riparian zone provide crucial shade over the water, which helps regulate water temperature. Cooler water holds more dissolved oxygen, a vital element for fish and other aquatic organisms. This is especially important in warmer climates or during hot summer months when water temperatures can become dangerously high for cold-water species like trout. The shade also reduces evaporation, helping to conserve water in the stream.

Flood Mitigation

During heavy rainfall or snowmelt, riparian zones act like sponges, absorbing excess water and slowing its flow. This natural flood control reduces the intensity of floodwaters, protecting downstream communities and infrastructure. The vegetation and complex topography of a healthy riparian area dissipate the energy of floodwaters, minimizing damage and allowing water to slowly infiltrate the ground, recharging groundwater reserves.

Components of a Healthy Riparian Zone

A thriving riparian zone is a complex system, but its health largely depends on a few key components working in harmony:

- Native Vegetation: The presence of diverse native plants is paramount. These species are adapted to the local climate and soil conditions, and their root systems are typically more effective at stabilizing banks and filtering pollutants than non-native species. A healthy riparian zone will feature a mix of trees (like cottonwoods, willows, sycamores), shrubs (dogwood, elderberry), and herbaceous plants (sedges, rushes, grasses). This layered vegetation provides varied habitats and maximizes ecological functions.

- Intact Soil Structure: The soil in a riparian zone is often rich in organic matter, thanks to decaying plant material. This organic content improves soil structure, enhances water retention, and supports a vibrant community of microorganisms that play a crucial role in nutrient cycling and pollutant breakdown.

- Hydrological Connection: A healthy riparian zone maintains a natural connection to the water body, allowing for regular inundation and groundwater exchange. This dynamic interaction is essential for the unique plant and animal communities that thrive there.

- Minimal Disturbance: Healthy riparian zones are relatively undisturbed by human activities such as excessive logging, grazing, or development. This allows natural processes to unfold, fostering resilience and ecological integrity.

Threats to Riparian Zones and Conservation Strategies

Despite their immense value, riparian zones are among the most threatened ecosystems globally. Human activities often degrade these vital areas, leading to severe ecological consequences.

Major Threats

- Agricultural Practices: Clearing riparian vegetation for crops or allowing livestock to graze directly on riverbanks can destroy plant cover, compact soil, and introduce pollutants.

- Urbanization and Development: Construction of homes, roads, and infrastructure often encroaches on riparian areas, replacing natural habitats with impervious surfaces and increasing runoff.

- Deforestation and Logging: Removal of trees in riparian zones eliminates shade, destabilizes banks, and reduces habitat.

- Pollution: Runoff from various sources can overwhelm the filtering capacity of riparian zones, introducing excessive nutrients, chemicals, and sediment directly into waterways.

- Invasive Species: Non-native plants can outcompete native riparian vegetation, reducing biodiversity and altering ecosystem functions. For example, tamarisk in the American Southwest can consume vast amounts of water and reduce habitat for native species.

- Altered Hydrology: Dams, diversions, and channelization projects can drastically change natural flow regimes, impacting the water availability and flood patterns that riparian ecosystems depend on.

Conservation and Restoration Strategies

Protecting and restoring riparian zones is a critical endeavor that requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Establishing Riparian Buffers: Creating or maintaining vegetated strips along waterways, often mandated by local regulations, helps filter runoff and stabilize banks. These buffers can vary in width depending on the land use and ecological goals.

- Reforestation and Revegetation: Planting native trees, shrubs, and grasses in degraded riparian areas helps restore ecological functions. This often involves removing invasive species first.

- Fencing and Livestock Management: Excluding livestock from riparian areas or implementing rotational grazing practices can allow vegetation to recover and prevent bank erosion.

- Sustainable Land Use Planning: Integrating riparian zone protection into urban planning and agricultural practices ensures that development and farming are conducted in an environmentally responsible manner.

- Public Education and Engagement: Raising awareness about the importance of riparian zones encourages community involvement in conservation efforts and promotes responsible stewardship.

Restoration and Management: Bringing Riparian Zones Back to Life

The good news is that riparian zones are remarkably resilient and can often be restored with careful planning and effort. Restoration projects typically involve several key steps:

- Assessment: Understanding the specific causes of degradation and the ecological potential of the site. This might involve soil analysis, hydrological studies, and surveys of existing vegetation and wildlife.

- Site Preparation: This could include removing invasive species, stabilizing severely eroded banks using bioengineering techniques (like live staking or fascines), or re-contouring the land to mimic natural floodplains.

- Revegetation: Planting a diverse array of native species appropriate for the specific site conditions. This often involves using locally sourced seeds or cuttings to ensure genetic compatibility and adaptation. For example, planting willow stakes directly into moist soil is a common and effective technique for bank stabilization.

- Monitoring and Maintenance: Post-restoration care is crucial. This includes watering newly planted vegetation, controlling invasive species, and monitoring the site’s progress over several years to ensure successful establishment and ecological recovery.

Successful restoration often requires collaboration between landowners, government agencies, conservation organizations, and local communities. Citizen science initiatives, where volunteers help with planting and monitoring, are powerful tools for engaging the public and expanding restoration efforts.

Conclusion

Riparian zones are far more than just riverbanks; they are dynamic, life-giving ecosystems that provide an astonishing array of benefits to both nature and humanity. From purifying our water and controlling floods to harboring incredible biodiversity and stabilizing our landscapes, their importance cannot be overstated. As we face increasing environmental challenges, recognizing, protecting, and restoring these vital green corridors becomes not just an ecological imperative, but a fundamental aspect of ensuring a healthy and sustainable future for all. Let us all become stewards of these invaluable natural treasures, ensuring that the vibrant life of our waterways continues to thrive.