In the intricate tapestry of life on Earth, every organism, from the smallest bacterium to the largest whale, relies on a fundamental process: the creation of organic matter. This essential act, which forms the very base of nearly all food webs, can occur in two primary ways. One involves the production of organic compounds within an ecosystem, a process known as autochthonous production. Understanding this concept is key to grasping how ecosystems function, sustain life, and respond to environmental changes.

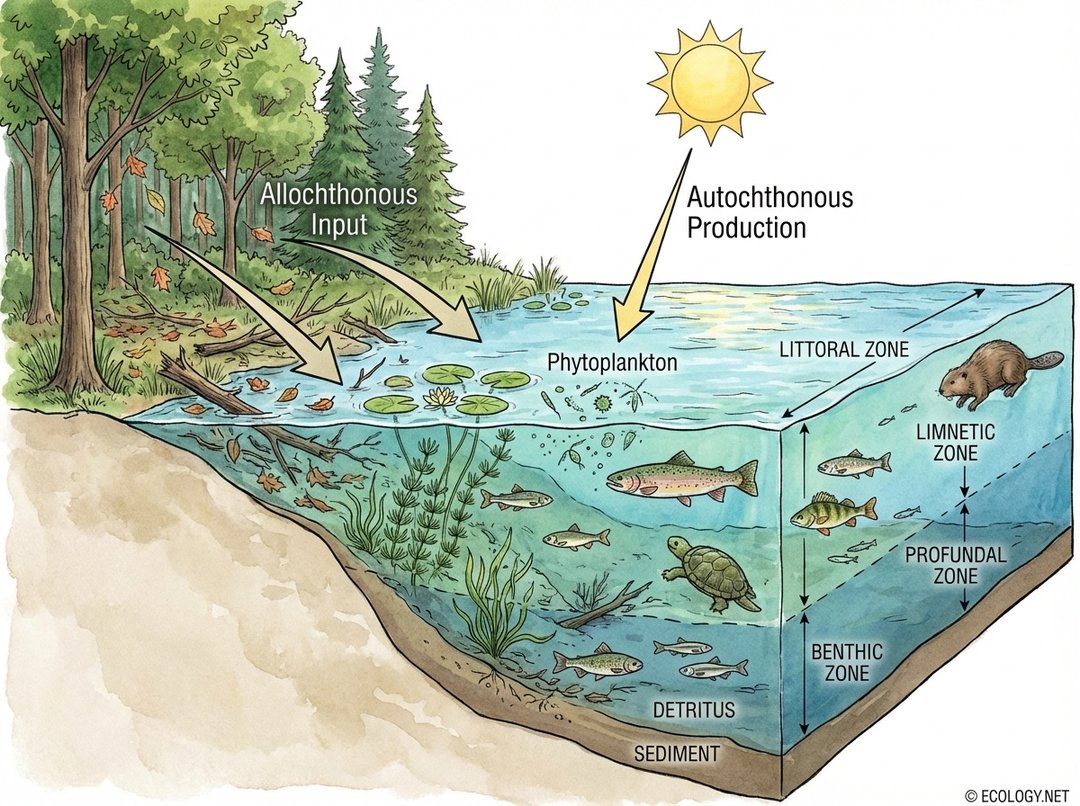

Autochthonous production refers to the synthesis of organic matter by organisms within the ecosystem itself. These organisms, often called primary producers, convert inorganic substances into organic compounds, essentially creating food from scratch. This stands in contrast to allochthonous input, which involves organic matter entering an ecosystem from an external source, such as leaves falling into a stream from a surrounding forest.

Consider a freshwater lake. The algae and aquatic plants growing within that lake, utilizing sunlight and nutrients, are engaging in autochthonous production. Meanwhile, leaves and twigs that fall into the lake from nearby trees represent allochthonous input. Both contribute to the lake’s energy budget, but their origins are fundamentally different.

The Core Mechanisms of Autochthonous Production

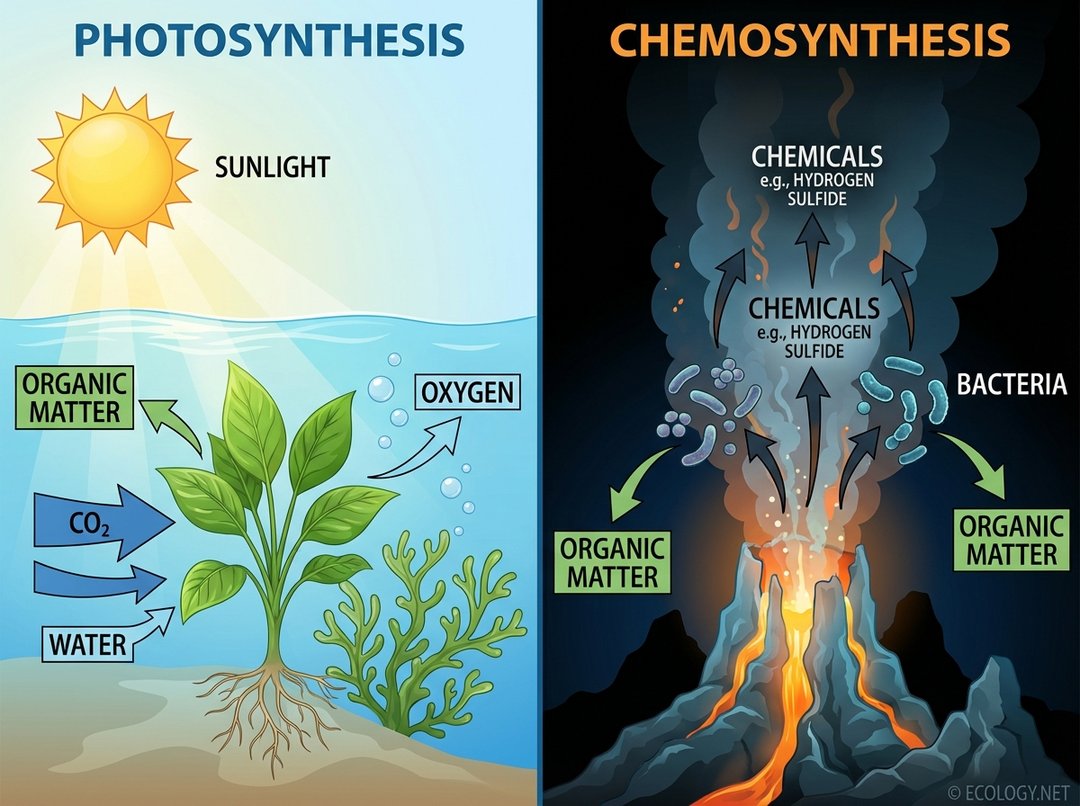

The creation of organic matter from inorganic sources is a marvel of biological engineering, primarily driven by two distinct processes: photosynthesis and chemosynthesis.

Photosynthesis: The Sun’s Energy Harvest

The most widely recognized form of autochthonous production is photosynthesis. This process is carried out by plants, algae, and certain bacteria, collectively known as photoautotrophs. They harness the energy from sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose, a simple sugar, and oxygen. This glucose serves as the foundational organic matter, providing energy and building blocks for the producers themselves and, subsequently, for all other organisms in the food web that consume them.

- Key Ingredients: Sunlight, carbon dioxide (CO2), water (H2O).

- Products: Glucose (C6H12O6), oxygen (O2).

- Examples:

- Terrestrial plants, from towering trees to microscopic mosses.

- Phytoplankton, the microscopic algae floating in oceans and lakes.

- Seaweeds and aquatic plants in marine and freshwater environments.

Chemosynthesis: Life in the Dark

While photosynthesis dominates most surface ecosystems, life finds a way even in the absence of sunlight. Chemosynthesis is a remarkable process where certain bacteria and archaea convert inorganic chemical compounds, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, or methane, into organic matter. This process is particularly prevalent in environments like deep-sea hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, and even within certain soils or caves, where sunlight cannot penetrate.

- Key Ingredients: Inorganic chemical compounds (e.g., hydrogen sulfide, methane), carbon dioxide, oxygen (sometimes).

- Products: Organic matter.

- Examples:

- Chemoautotrophic bacteria living around deep-sea hydrothermal vents, forming the base of unique ecosystems.

- Bacteria in certain soils that oxidize nitrogen or sulfur compounds.

The Indispensable Role of Autochthonous Production in Ecosystems

Autochthonous production is not merely an academic concept; it is the engine that drives nearly all life on Earth. Without it, the vast majority of ecosystems would collapse, as there would be no initial source of organic energy to fuel the food web.

Foundation of Food Webs

Primary producers, through autochthonous production, are the first trophic level in almost every ecosystem. They convert inorganic energy into a usable organic form, which is then consumed by herbivores (primary consumers), who are in turn eaten by carnivores (secondary and tertiary consumers). This continuous flow of energy, originating from autochthonous production, sustains all higher life forms.

Driving Nutrient Cycles

As primary producers take up inorganic nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon from their environment, they incorporate them into organic compounds. When these producers are consumed or decompose, these nutrients are cycled back into the ecosystem, making them available for new growth. Autochthonous production is therefore intimately linked to the global biogeochemical cycles that regulate Earth’s climate and support biodiversity.

Biodiversity Hotspots

Ecosystems with high rates of autochthonous production often boast incredible biodiversity. Consider the vibrant coral reefs, rainforests, or productive estuaries. The abundance of primary producers provides a rich and varied food source, creating numerous niches for a wide array of species.

A coral reef, for instance, is a prime example of an ecosystem heavily reliant on autochthonous production. The corals themselves host symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae, which photosynthesize and provide the corals with vital nutrients. This internal production, combined with other photosynthetic organisms like seaweeds and phytoplankton, creates an incredibly productive and biodiverse environment.

Factors Influencing Autochthonous Production Rates

The rate at which autochthonous production occurs is not constant; it is influenced by a complex interplay of environmental factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for predicting ecosystem health and productivity.

- Light Availability: For photosynthetic organisms, sunlight is the ultimate energy source. Factors like water depth, turbidity, cloud cover, and shading can significantly impact light penetration and, consequently, production rates.

- Nutrient Availability: Essential nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron are vital for growth. Scarcity of any one of these can limit production, while an excess can sometimes lead to phenomena like algal blooms.

- Temperature: Every organism has an optimal temperature range for metabolic processes. Extreme temperatures, whether too hot or too cold, can inhibit or halt autochthonous production.

- Water Availability: Terrestrial plants require sufficient water for photosynthesis and nutrient transport. In aquatic systems, water itself is the medium, but factors like salinity can become critical.

- Carbon Dioxide Concentration: As a key ingredient for photosynthesis and chemosynthesis, the availability of CO2 can influence production rates, especially in aquatic environments where its solubility is a factor.

- Grazing Pressure: While not directly influencing the *potential* for production, intense grazing by herbivores can reduce the standing biomass of primary producers, impacting the overall ecosystem’s productivity and energy transfer.

Autochthonous Production Across Diverse Ecosystems

The significance of autochthonous production varies across different types of ecosystems, shaping their unique characteristics.

Aquatic Ecosystems

In most aquatic environments, autochthonous production is the dominant source of energy. Phytoplankton in the open ocean are responsible for a vast percentage of global oxygen production and form the base of marine food webs. In lakes and rivers, algae and aquatic macrophytes play a similar role. Deep-sea ecosystems, powered by chemosynthesis around hydrothermal vents, are entirely reliant on autochthonous production in an environment devoid of sunlight.

Terrestrial Ecosystems

On land, plants are the primary autochthonous producers, forming the foundation of forests, grasslands, and deserts. While terrestrial ecosystems also receive allochthonous inputs (e.g., decaying organic matter from neighboring areas), the vast majority of energy is generated internally through photosynthesis.

Human Impact and the Future of Autochthonous Production

Human activities have profound impacts on the rates and patterns of autochthonous production globally. Understanding these impacts is crucial for conservation and sustainable management.

- Eutrophication: Excess nutrient runoff from agriculture and wastewater can lead to over-enrichment of aquatic ecosystems, causing massive algal blooms. While initially boosting autochthonous production, these blooms can lead to oxygen depletion (hypoxia) when they decompose, creating “dead zones” harmful to other aquatic life.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and ocean acidification can directly affect the physiology of primary producers. For example, ocean acidification threatens calcifying organisms like corals and some phytoplankton, which are vital autochthonous producers.

- Pollution: Toxins and pollutants can directly inhibit the growth and photosynthetic capabilities of primary producers, reducing overall ecosystem productivity.

- Habitat Destruction: The clearing of forests, conversion of wetlands, or destruction of coral reefs directly removes primary producers, diminishing autochthonous production and the ecosystem services they provide.

Protecting and restoring ecosystems means safeguarding the conditions that allow autochthonous production to thrive. This includes managing nutrient runoff, mitigating climate change, reducing pollution, and conserving critical habitats. The health of our planet, and indeed our own species, is inextricably linked to the ability of primary producers to continue their essential work of creating life from the raw materials of the Earth.

Conclusion

Autochthonous production stands as a cornerstone of ecology, representing the fundamental process by which life generates its own sustenance from inorganic sources. Whether powered by the sun’s radiant energy through photosynthesis or by chemical reactions in the deep, dark reaches of the Earth via chemosynthesis, this internal creation of organic matter forms the bedrock of virtually every ecosystem. From the vibrant biodiversity of a coral reef to the vast expanses of the open ocean, the intricate dance of life begins with these primary producers. Recognizing their indispensable role and the factors that influence them is not just an academic exercise; it is a vital step towards understanding, appreciating, and ultimately preserving the delicate balance of our planet’s living systems.