Imagine a vibrant forest stream, teeming with life. What fuels this bustling miniature world? Is it just the sunlight hitting the water, or is there something more? The answer often lies in a fascinating ecological concept known as allochthonous inputs. This term, while sounding complex, describes a fundamental process that underpins the health and productivity of countless ecosystems around the globe.

What Exactly Are Allochthonous Inputs?

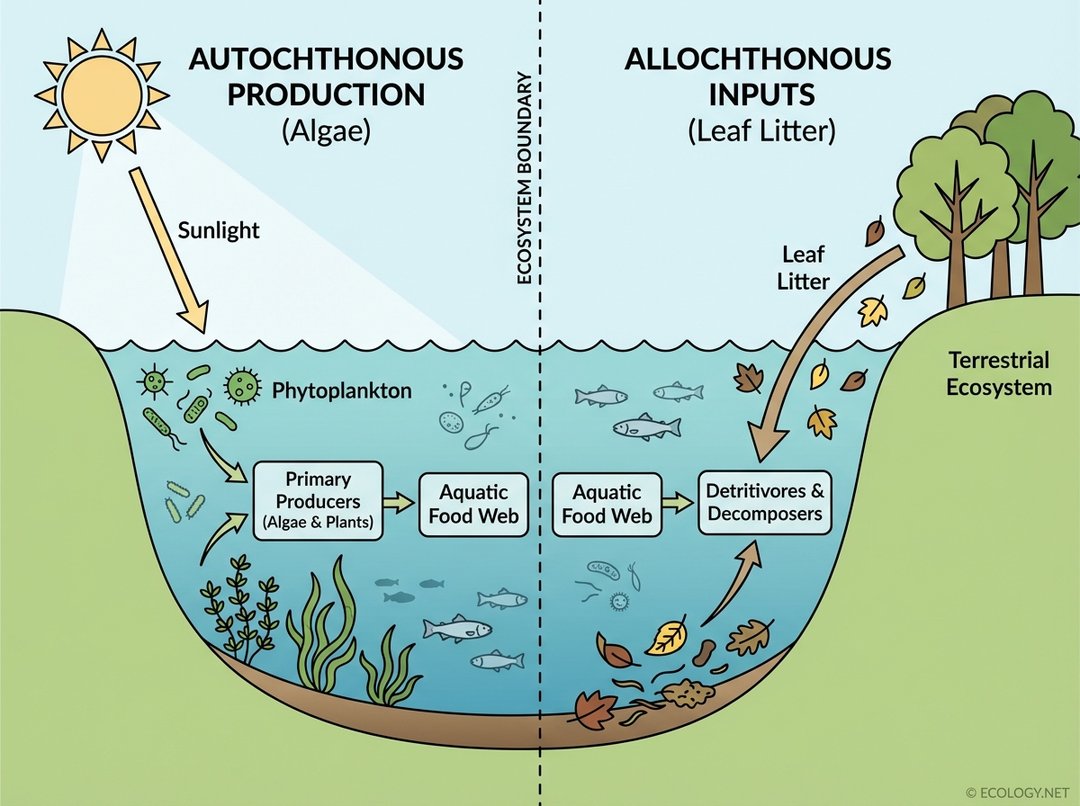

In ecology, an ecosystem is a community of living organisms interacting with their non-living environment. Every ecosystem has boundaries, whether they are distinct, like the edge of a lake, or more diffuse, like a transition zone in a forest. Allochthonous inputs refer to organic matter and nutrients that originate outside these ecosystem boundaries and are then transported into the system.

Think of it as an external delivery service for energy and building blocks. These materials are not produced within the ecosystem itself but are crucial for its functioning. Without these external contributions, many ecosystems would look and behave very differently, often supporting far less life.

The concept is straightforward: materials from the surrounding landscape, such as a forest, are carried into an aquatic environment like a lake or stream. These inputs can be anything from fallen leaves to dissolved minerals, all playing a vital role in the internal dynamics of the receiving ecosystem.

Common Types of Allochthonous Inputs

Allochthonous inputs come in many forms, each contributing uniquely to the receiving ecosystem. Understanding these different types helps us appreciate the intricate connections between landscapes and the water bodies they encompass.

- Leaf Litter and Terrestrial Organic Matter: Perhaps the most iconic allochthonous input, especially in forested areas. Leaves, twigs, bark, and even whole branches fall from trees and are carried by wind or water into streams, rivers, and lakes. This material forms the base of many detritus-based food webs.

- Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC): Rainwater percolating through soil picks up dissolved organic compounds, which are then transported into aquatic systems via runoff and groundwater flow. DOC is a critical energy source for microbes and can influence water chemistry and light penetration.

- Sediment Runoff: After heavy rains, soil particles, along with any attached organic matter and nutrients, can be washed from land into water bodies. While excessive sediment can be detrimental, natural levels contribute to substrate formation and nutrient cycling.

- Nutrients from Rainfall and Atmospheric Deposition: Rain itself carries dissolved nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, which originate from the atmosphere. These can directly enter aquatic systems or be deposited on land and subsequently washed in.

- Migratory Organisms: While less intuitive, the bodies of migratory animals, such as salmon swimming upstream to spawn and die, represent a significant allochthonous input of organic matter and nutrients into freshwater systems. Their carcasses provide a rich food source for scavengers and decomposers.

- Insects and Terrestrial Invertebrates: Insects falling from riparian vegetation into streams and lakes provide an immediate food source for fish and other aquatic predators.

These diverse inputs highlight that ecosystems are rarely isolated. They are constantly interacting with and influenced by their surroundings, creating a complex web of dependencies.

Allochthonous vs. Autochthonous Production: A Crucial Distinction

To fully grasp the importance of allochthonous inputs, it is essential to understand their counterpart: autochthonous production. This distinction is fundamental to how ecologists categorize the primary sources of energy and organic matter within an ecosystem.

- Autochthonous Production: Refers to organic matter that is produced within the ecosystem itself. The most common form is photosynthesis by algae, aquatic plants, and cyanobacteria, which convert sunlight into energy. In a lake, for example, the growth of phytoplankton (microscopic algae) is a prime example of autochthonous production.

- Allochthonous Inputs: As we have discussed, these are organic materials and nutrients that originate outside the ecosystem and are transported in.

Many ecosystems rely on a balance of both. For instance, a large, deep lake with clear water might have significant autochthonous production due to abundant sunlight penetrating the water column, fueling algal growth. Conversely, a small, shaded forest stream might be heavily reliant on allochthonous inputs like leaf litter from the surrounding trees because limited sunlight restricts internal primary production.

The relative importance of allochthonous versus autochthonous sources can vary greatly depending on the ecosystem’s size, depth, light availability, and the characteristics of its surrounding landscape. This balance dictates the structure of the food web and the overall productivity of the system.

The Ecological Significance of Allochthonous Inputs

Why do ecologists pay so much attention to these external deliveries? Because allochthonous inputs are far more than just “stuff” entering an ecosystem; they are vital drivers of ecological processes.

Fueling Food Webs

In many ecosystems, particularly small, shaded streams and rivers, allochthonous organic matter forms the base of the food web. Instead of grazing on living plants or algae, many aquatic invertebrates, known as detritivores or shredders, feed directly on decomposing leaves and wood. These invertebrates are then consumed by larger predators like fish, effectively transferring energy from the terrestrial environment into the aquatic food web.

Consider a small, headwater stream flowing through a dense forest. The canopy overhead blocks much of the sunlight, limiting the growth of algae. Here, fallen leaves become the primary energy source. Caddisfly larvae, stonefly nymphs, and other invertebrates shred and consume these leaves, breaking them down into smaller particles. These smaller particles and the invertebrates themselves then become food for fish and other aquatic organisms, demonstrating a direct link between the forest and the stream’s inhabitants.

Nutrient Cycling and Water Chemistry

Allochthonous inputs bring essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon into ecosystems. These nutrients are crucial for the growth of primary producers (algae, plants) and subsequent trophic levels. The decomposition of allochthonous organic matter also influences water chemistry, affecting pH, dissolved oxygen levels, and the availability of other trace elements.

Habitat Structure and Biodiversity

Large woody debris, such as fallen trees and branches, is a significant allochthonous input in many aquatic systems. This debris creates complex habitats, providing shelter for fish and invertebrates, altering water flow, and creating areas of deposition and scour. These structural elements increase habitat diversity, which in turn supports a greater variety of species.

Connecting Ecosystems

Allochthonous inputs are a powerful illustration of ecosystem connectivity. They demonstrate that terrestrial and aquatic environments are not isolated entities but are intimately linked. Changes in one system, such as deforestation in a riparian zone, can have profound and immediate impacts on the adjacent aquatic ecosystem by altering the quantity and quality of allochthonous inputs.

Factors Influencing Allochthonous Inputs

The amount and type of allochthonous inputs an ecosystem receives are not constant; they are influenced by a variety of environmental and anthropogenic factors.

Riparian Vegetation

The type and density of vegetation along the banks of a stream or lake are paramount. A dense forest canopy provides abundant leaf litter and woody debris, while a grassland or agricultural field will contribute far less organic matter but potentially more sediment and dissolved nutrients from fertilizers.

Climate and Hydrology

- Rainfall: Higher rainfall generally leads to increased runoff, carrying more dissolved and particulate matter from the land into water bodies.

- Temperature: Influences the rate of decomposition of organic matter on land, affecting the form in which it enters the aquatic system.

- Flow Regimes: The frequency and intensity of floods can dramatically increase the transport of allochthonous materials, including large woody debris.

Topography and Geology

Steeper slopes tend to generate more rapid runoff and sediment transport. The underlying geology influences soil composition and the types of dissolved minerals that enter aquatic systems.

Land Use and Human Activities

Human activities have a profound impact on allochthonous inputs:

- Deforestation: Reduces leaf litter and woody debris, increases light penetration (potentially boosting autochthonous production), and often leads to increased sediment runoff.

- Agriculture: Can introduce excess nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus) from fertilizers and pesticides, as well as increased sediment loads.

- Urbanization: Impervious surfaces (roads, buildings) increase stormwater runoff, carrying pollutants, sediments, and altered thermal regimes into aquatic systems.

- Dam Construction: Can alter natural flow regimes, trapping sediments and organic matter upstream and reducing downstream allochthonous inputs.

Case Studies: Allochthonous Inputs in Action

Temperate Forest Streams

These are classic examples of allochthonous-driven ecosystems. During autumn, a massive influx of leaves provides a seasonal pulse of energy. Specialized invertebrates, like shredders, are adapted to process this coarse particulate organic matter (CPOM). Their activity is crucial for breaking down leaves into finer particles that can be consumed by other organisms or further decomposed by microbes.

Arctic Tundra Lakes

While seemingly barren, many Arctic lakes receive significant allochthonous inputs from surrounding tundra vegetation, especially during the short summer thaw. This terrestrial organic matter can be a major carbon source, influencing the lake’s carbon cycle and supporting microbial communities in an environment where autochthonous production might be limited by cold temperatures and short growing seasons.

Estuaries and Coastal Waters

Estuaries, where rivers meet the sea, are often rich in allochthonous inputs from upstream river systems. These inputs include dissolved organic matter, sediments, and nutrients, which can fuel high productivity in these transitional zones, supporting diverse fish and shellfish populations.

Conclusion: The Unseen Threads of Connection

Allochthonous inputs are a powerful reminder that ecosystems are not isolated islands but are intricately connected to their surrounding landscapes. These external deliveries of organic matter and nutrients are fundamental to the energy flow, nutrient cycling, and structural complexity of countless aquatic and even some terrestrial environments.

From the humble leaf falling into a stream to the dissolved carbon washing into a lake, allochthonous inputs weave unseen threads of connection, sustaining food webs, shaping habitats, and influencing water chemistry. Understanding these processes is not just an academic exercise; it is crucial for effective conservation and management, allowing us to appreciate the delicate balance that sustains life across our planet.

The next time you gaze upon a tranquil lake or a babbling brook, remember the hidden contributions from beyond its banks. These allochthonous inputs are the unsung heroes, constantly nourishing and shaping the vibrant ecosystems we cherish.