Unmasking Overexploitation: When Humanity Takes Too Much

The natural world provides an incredible bounty, from the air we breathe to the food we eat and the materials that build our societies. Yet, there’s a critical point where our demands can outstrip nature’s capacity to regenerate. This dangerous imbalance is known as overexploitation, a pervasive environmental challenge that threatens the very resources we depend upon. Understanding overexploitation is not just for scientists; it is crucial for anyone who cares about the health of our planet and the future of humanity.

What is Overexploitation? The Basics

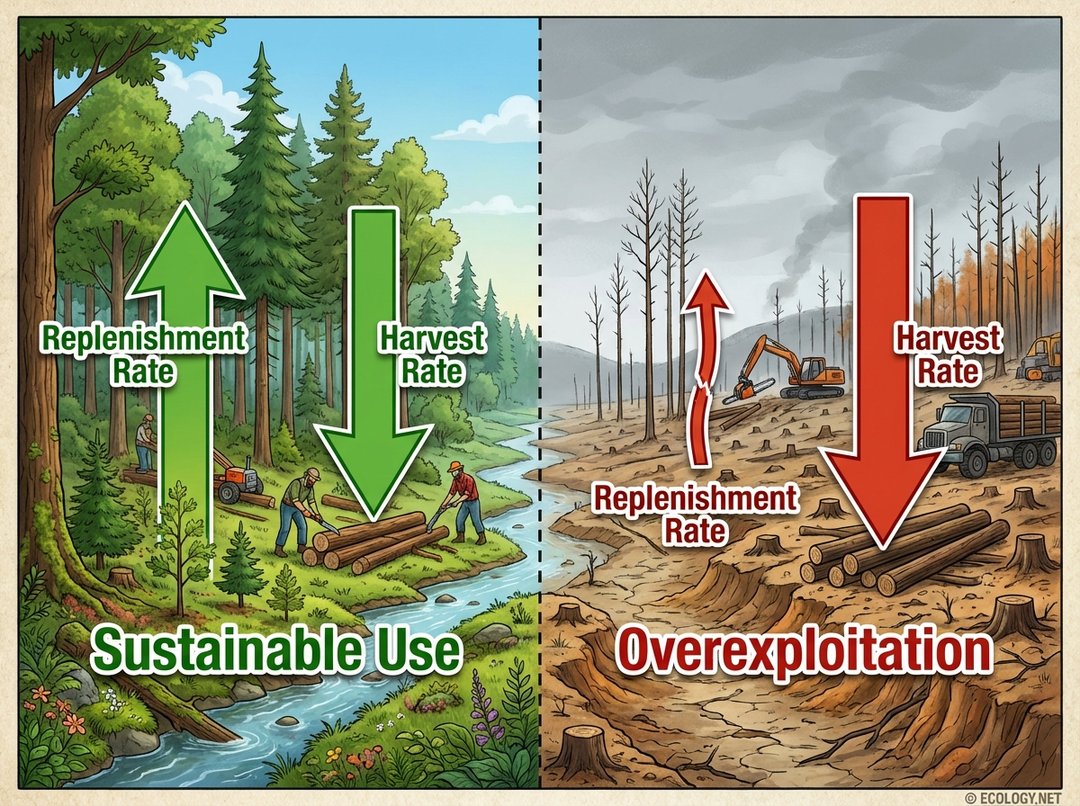

At its core, overexploitation occurs when a renewable resource is consumed or harvested at a rate faster than it can replenish itself. Think of it as spending your savings faster than you earn money; eventually, your account will be empty. Renewable resources, by definition, have the capacity to regenerate, but this capacity is not infinite. Forests can regrow, fish populations can rebound, and groundwater can be recharged, but only if given sufficient time and conditions. When human activities consistently exceed these natural recovery rates, the resource dwindles, leading to scarcity, ecological damage, and often, irreversible loss.

This fundamental imbalance is the defining characteristic of overexploitation. It is a stark contrast to sustainable use, where harvest rates are carefully managed to match or remain below the natural replenishment rate, ensuring the resource remains available for future generations.

The Many Faces of Overexploitation: Types and Examples

Overexploitation manifests in various forms across different ecosystems, impacting a wide array of species and resources.

Overfishing: Emptying the Oceans

Perhaps one of the most widely recognized forms, overfishing involves catching fish faster than they can reproduce. Modern fishing technologies, including massive trawlers and sophisticated sonar, have dramatically increased our capacity to extract marine life.

- Atlantic Cod: A classic and tragic example is the collapse of the Atlantic Cod fishery off the coast of Newfoundland in the early 1990s. Decades of intensive fishing, driven by demand and technological advancements, decimated what was once one of the world’s richest fishing grounds. The population plummeted, leading to a moratorium that remains largely in place, with little sign of full recovery.

- Bluefin Tuna: Highly prized in sushi markets, several populations of Bluefin Tuna across the Atlantic and Pacific have been severely overfished, pushing them towards endangered status despite international efforts to regulate catches.

Overhunting and Poaching: Vanishing Wildlife

Terrestrial animals are also vulnerable, particularly those with slow reproductive rates or high commercial value.

- Rhinos and Elephants: Poaching for rhino horn and elephant ivory continues to drive these iconic species towards extinction. Despite international bans, illegal wildlife trade fuels a lucrative black market, making conservation a constant uphill battle.

- Passenger Pigeon: A historical example, the Passenger Pigeon, once numbering in the billions, was hunted to extinction in the early 20th century due to commercial hunting and habitat loss. Its rapid disappearance serves as a stark warning of humanity’s capacity for destruction.

Overlogging and Deforestation: Stripping the Land

Forests are vital for biodiversity, climate regulation, and numerous ecosystem services. Overlogging, especially illegal logging and clear-cutting without adequate reforestation, leads to deforestation.

- Amazon Rainforest: Vast areas of the Amazon, the “lungs of the Earth,” are cleared annually for cattle ranching, agriculture (soybean cultivation), and timber, leading to significant biodiversity loss and carbon emissions.

- Old-Growth Forests: Many ancient, old-growth forests around the world, which take centuries to develop, are irreplaceable once cut down, representing a permanent loss of unique ecological structures and species.

Overgrazing: Desertification’s Advance

When livestock graze on pastures at densities too high or for durations too long, they consume vegetation faster than it can regrow. This can lead to soil erosion, compaction, and ultimately, desertification.

- Sahel Region: In parts of the Sahel region of Africa, overgrazing combined with drought has contributed to the expansion of desert-like conditions, impacting the livelihoods of millions.

Over-extraction of Groundwater: Draining the Depths

Even seemingly abundant underground water resources can be overexploited. Aquifers, which are underground layers of water-bearing permeable rock, can take thousands of years to replenish.

- Ogallala Aquifer: One of the world’s largest aquifers, underlying parts of eight U.S. states, is being depleted at an alarming rate, primarily for agricultural irrigation, far exceeding its natural recharge rate. This poses a significant threat to future food production in the region.

The Ecological Consequences of Overexploitation

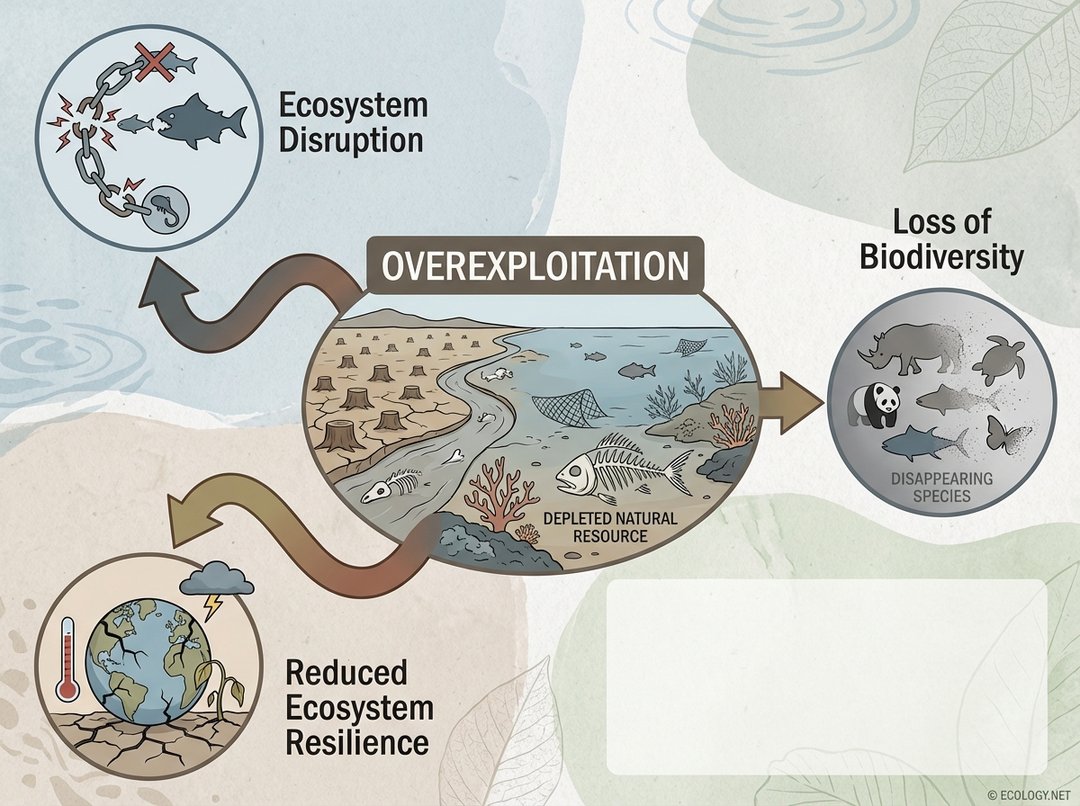

The impacts of overexploitation extend far beyond the immediate depletion of a single resource. It triggers a cascade of effects that can unravel entire ecosystems, leading to profound and often irreversible changes.

Ecosystem Disruption and Trophic Cascades

Every species plays a role in its ecosystem. When one species is overexploited, it can disrupt delicate food webs and ecological relationships.

- Predator-Prey Imbalances: Overfishing of top predators like sharks can lead to an explosion in the populations of their prey, which in turn can overgraze kelp forests or coral reefs, fundamentally altering marine habitats.

- Habitat Degradation: Overlogging not only removes trees but also destroys the habitat for countless other species, from insects and birds to larger mammals, leading to their decline or displacement.

Loss of Biodiversity

Overexploitation is a primary driver of biodiversity loss. When populations of a species are driven down to critically low levels, they become more vulnerable to disease, genetic inbreeding, and environmental changes, increasing their risk of extinction.

- Genetic Erosion: Even if a species survives, severe overexploitation can drastically reduce its genetic diversity, making it less adaptable to future environmental shifts.

- Extinction: The ultimate consequence, where a species is completely wiped out, representing an irreplaceable loss to the planet’s biological heritage.

Reduced Ecosystem Resilience

Healthy ecosystems are resilient; they can absorb disturbances and recover. Overexploitation weakens this resilience.

- Vulnerability to Climate Change: A deforested landscape is more prone to soil erosion and less able to regulate local climate, making it more vulnerable to extreme weather events.

- Disease Outbreaks: Reduced biodiversity can make ecosystems more susceptible to widespread disease outbreaks, as there are fewer species to act as buffers or provide natural resistance.

Socio-Economic Impacts

Beyond ecology, overexploitation has severe human consequences, particularly for communities that depend directly on natural resources for their livelihoods, leading to poverty, conflict, and displacement.

Drivers Behind the Depletion: Why Does Overexploitation Happen?

Understanding the root causes of overexploitation is essential for developing effective solutions. It is often a complex interplay of economic, social, and political factors.

- Economic Incentives: The pursuit of profit is a powerful driver. High demand and prices for certain resources (e.g., exotic timber, rare seafood, minerals) can incentivize unsustainable harvesting practices, especially in the absence of strong regulations.

- Poverty and Livelihood Needs: In many developing regions, communities may have limited alternatives and rely heavily on natural resources for survival, sometimes leading to unsustainable practices out of necessity.

- Technological Advancements: While beneficial in many ways, technological innovations in harvesting (e.g., larger fishing vessels, more efficient logging equipment) can dramatically increase extraction capacity, making it easier to overexploit resources.

- Population Growth and Increased Demand: A growing global population naturally places greater demands on natural resources for food, energy, and materials.

- Weak Governance and Enforcement: Inadequate laws, poor enforcement, corruption, and a lack of political will can allow illegal and unsustainable practices to flourish.

- Lack of Awareness and Education: A lack of understanding about the ecological limits of resources or the long-term consequences of overexploitation can contribute to unsustainable behaviors.

- Tragedy of the Commons: This economic theory describes a situation where individuals, acting independently and rationally according to their own self-interest, deplete a shared limited resource, even when it is clear that it is not in anyone’s long-term interest for this to happen.

Moving Towards Sustainability: Solutions and Mitigation

Addressing overexploitation requires a multi-faceted approach involving governments, industries, communities, and individuals.

- Effective Governance and Regulation:

- Quotas and Catch Limits: Scientifically determined limits on how much can be harvested.

- Protected Areas: Establishing marine protected areas, national parks, and wildlife reserves to allow populations to recover and habitats to thrive.

- Enforcement: Robust monitoring, surveillance, and legal action against illegal activities.

- Sustainable Resource Management:

- Certification Schemes: Programs like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) or Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certify products from sustainably managed sources, empowering consumers.

- Selective Harvesting: Practices that minimize damage to the ecosystem and allow younger individuals to mature.

- Restoration Efforts: Reforestation, habitat restoration, and reintroduction programs for depleted species.

- Technological Innovation:

- Improved Fishing Gear: Developing gear that reduces bycatch (unintended species caught) and minimizes habitat damage.

- Precision Agriculture: Technologies that optimize water and land use, reducing pressure on groundwater and forests.

- Economic Alternatives and Incentives:

- Ecotourism: Providing economic benefits from conservation rather than exploitation.

- Support for Sustainable Livelihoods: Helping communities develop alternative income sources that do not rely on overexploiting resources.

- Public Awareness and Consumer Choice:

- Education: Informing the public about the impacts of overexploitation and the importance of sustainable choices.

- Conscious Consumption: Choosing sustainably sourced products, reducing consumption, and supporting businesses committed to ethical practices.

- International Cooperation:

- Many resources, like migratory fish stocks or shared forests, cross national borders, requiring international agreements and collaborative management efforts.

A Call to Balance: Securing Our Natural Heritage

Overexploitation is a stark reminder that our planet’s resources, though renewable, are not limitless. The stories of depleted fisheries, vanishing forests, and endangered wildlife serve as powerful lessons in the delicate balance between human needs and ecological capacity. By understanding the mechanisms, consequences, and drivers of overexploitation, we can move beyond simply reacting to crises and instead proactively build a future where humanity thrives in harmony with the natural world. The path forward demands responsible stewardship, innovative solutions, and a collective commitment to ensuring that the bounty of nature remains for generations to come.