Understanding Reforestation: Restoring Earth’s Vital Green Lungs

The planet’s forests are more than just collections of trees; they are intricate, living systems vital for all life on Earth. Yet, these invaluable ecosystems face unprecedented threats from deforestation. In response, reforestation emerges as a powerful and essential strategy to heal our planet. This practice involves much more than simply planting trees; it is a complex, science-backed endeavor aimed at restoring ecological balance and securing a sustainable future.

Reforestation Versus Afforestation: A Crucial Distinction

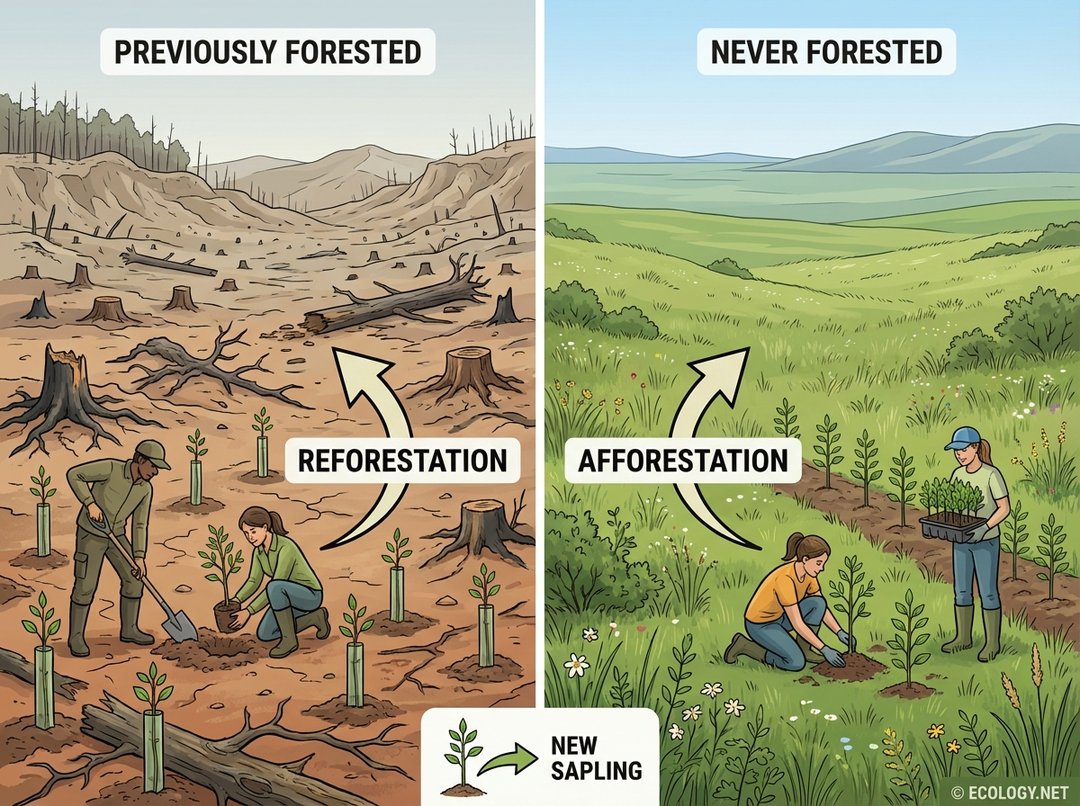

Before delving into the profound impacts of reforestation, it is important to clarify its precise meaning and differentiate it from a related but distinct practice: afforestation. While both involve planting trees, their starting points and ecological contexts are fundamentally different.

Reforestation refers to the natural or intentional restocking of existing forests that have been depleted, usually through deforestation, logging, or natural disturbances like wildfires. The key here is that the land was previously forested. The goal is to bring the forest back to its former glory, often using native species that once thrived there. Imagine a logging site where new saplings are planted; that is reforestation.

Afforestation, on the other hand, is the establishment of a forest or stand of trees in an area where there was no previous tree cover. This could be a vast grassland, an agricultural field that has been abandoned, or even a desert fringe. The aim is to create a new forest ecosystem where one did not exist before. Planting trees in a barren pasture to create a new woodland would be an example of afforestation.

Both practices are critical for increasing global tree cover, but reforestation often focuses on ecological restoration and recovery, while afforestation aims at creating new ecological assets.

The Urgent Imperative for Reforestation

The need for widespread reforestation has never been more pressing. Centuries of deforestation for agriculture, urbanization, and resource extraction have stripped vast areas of their natural forest cover. This loss has dire consequences, contributing significantly to some of the most critical environmental challenges of our time.

- Climate Change: Forests are massive carbon sinks, absorbing vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. When forests are destroyed, this stored carbon is released, exacerbating global warming. Reforestation helps reverse this trend by drawing carbon back into living biomass and soil.

- Biodiversity Loss: Tropical rainforests, in particular, are biodiversity hotspots, home to an estimated 80 percent of the world’s terrestrial species. Deforestation leads directly to habitat destruction, pushing countless species towards extinction. Reforestation provides a pathway to restore these vital habitats.

- Soil Degradation and Erosion: Tree roots bind soil, preventing erosion by wind and water. When forests are cleared, especially on slopes, topsoil can be rapidly lost, leading to desertification and reduced agricultural productivity.

- Water Cycle Disruption: Forests play a crucial role in the water cycle, influencing rainfall patterns, regulating water flow, and filtering water. Their removal can lead to increased flooding, droughts, and reduced water quality.

The Multifaceted Benefits of a Restored Forest

The positive impacts of reforestation ripple through every aspect of our environment and society. It is a powerful tool for ecological recovery and sustainable development.

The benefits extend far beyond simply having more trees:

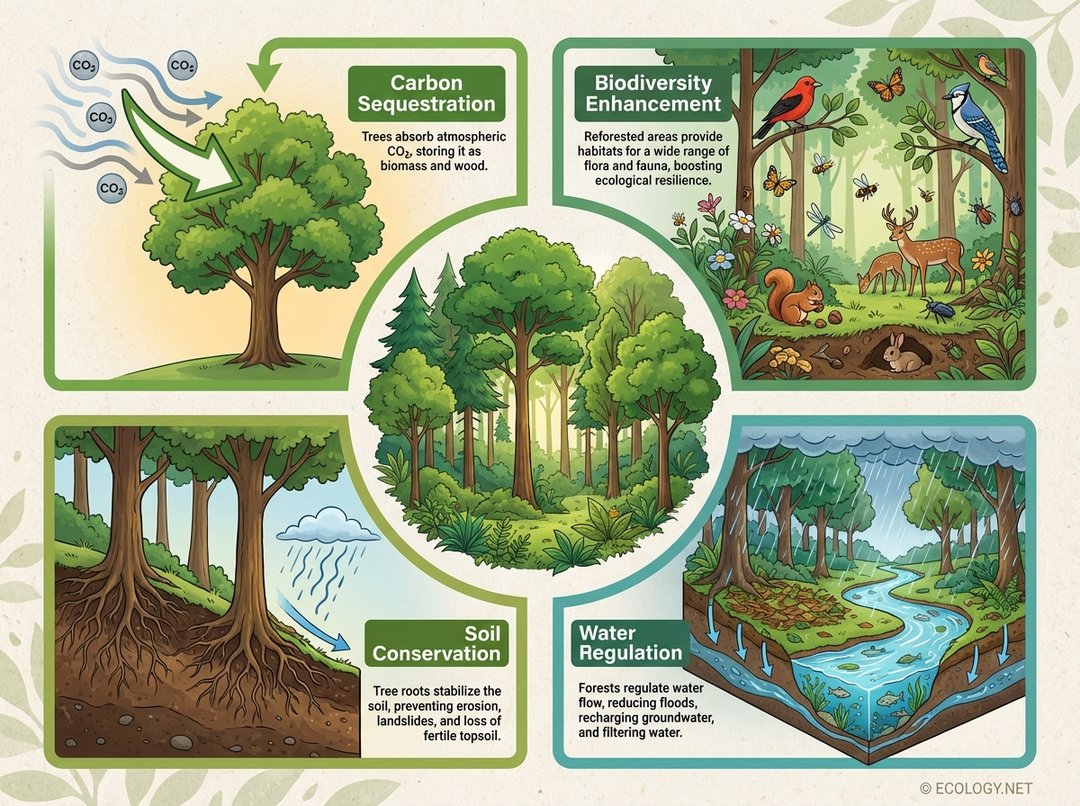

- Carbon Sequestration: As trees grow, they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, storing carbon in their wood, leaves, and roots. This process is fundamental in mitigating climate change. A mature forest can store hundreds of tons of carbon per hectare.

- Biodiversity Enhancement: Restored forests provide essential habitats, food sources, and migratory corridors for a vast array of wildlife, from insects and birds to large mammals. This helps to reverse biodiversity loss and maintain healthy, resilient ecosystems.

- Soil Conservation: The extensive root systems of trees stabilize soil, preventing erosion from rain and wind. The leaf litter and decaying organic matter on the forest floor also enrich the soil, improving its structure and fertility.

- Water Regulation: Forest canopies intercept rainfall, reducing the impact of heavy downpours and allowing water to slowly infiltrate the ground. This recharges groundwater, reduces surface runoff, and helps prevent floods. Forests also filter pollutants, improving water quality in rivers and streams.

- Air Quality Improvement: Trees filter pollutants from the air, including particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and sulfur dioxide, contributing to cleaner air for human health.

- Economic and Social Benefits: Reforestation projects can create jobs, provide sustainable timber and non-timber forest products, support ecotourism, and offer cultural and recreational opportunities for communities.

The Science Behind Successful Reforestation

Effective reforestation is not a simple matter of randomly planting saplings. It requires careful planning, scientific understanding, and long-term commitment.

Species Selection and Diversity

One of the most critical aspects is selecting the right tree species. Native species are almost always preferred because they are adapted to the local climate and soil conditions, are more resistant to local pests and diseases, and support native wildlife. Planting a diverse mix of species, rather than a monoculture, creates a more resilient ecosystem that is better able to withstand environmental changes and disease outbreaks. For example, a reforestation project in a degraded tropical forest might focus on fast-growing pioneer species to establish initial cover, followed by slower-growing climax species to restore the full forest structure.

Site Preparation and Planting Techniques

The success of new plantings often hinges on proper site preparation. This can involve clearing invasive weeds, improving soil quality through organic amendments, or creating microclimates that favor seedling survival. Various planting techniques are employed, from manual planting of individual saplings to direct seeding, depending on the scale of the project, terrain, and species. Advanced techniques like drone seeding are also being explored for large, inaccessible areas.

Long-Term Management and Monitoring

Reforestation is not a “plant and forget” operation. Young forests require ongoing care, including protection from grazing animals, fire management, and control of invasive species. Regular monitoring helps assess growth rates, survival rates, and overall ecosystem health, allowing for adjustments to management strategies as needed.

The Hidden World Beneath Our Feet: Mycorrhizal Networks

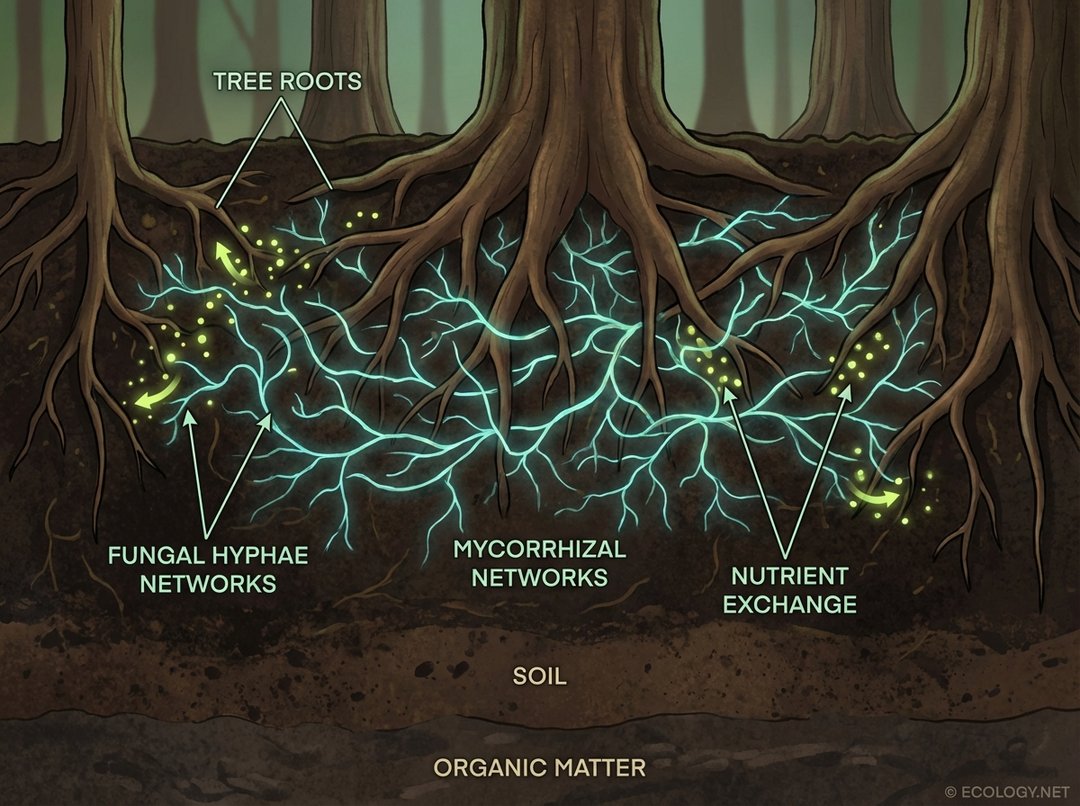

Beneath the visible grandeur of a forest lies an unseen, intricate network that is absolutely vital for its health and resilience: mycorrhizal networks. This concept, often referred to as the “Wood Wide Web,” highlights one of the most fascinating symbiotic relationships in nature.

Mycorrhizae are a symbiotic association between a fungus and the roots of a plant. The word “mycorrhiza” literally means “fungus root.” These fungi form extensive networks of delicate, thread-like structures called hyphae that extend far beyond the reach of the tree’s own roots, permeating the soil.

A Symbiotic Partnership

The relationship is mutually beneficial:

- For the Tree: The fungal hyphae act as an extension of the tree’s root system, vastly increasing its surface area for absorbing water and essential nutrients, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, which can be scarce in soil. The fungi can also protect trees from pathogens and improve their tolerance to environmental stresses like drought.

- For the Fungus: In return, the tree, through photosynthesis, produces sugars and other carbohydrates that it shares with the fungus. Fungi cannot photosynthesize, so they rely on their plant partners for these vital energy sources.

The Wood Wide Web

These mycorrhizal networks can connect multiple trees, even different species, allowing for the exchange of nutrients, water, and even chemical signals between them. This “Wood Wide Web” facilitates communication and resource sharing within a forest ecosystem. For example, older, established “mother trees” can use these networks to send nutrients to younger, struggling saplings, enhancing their survival rates.

Understanding and fostering these mycorrhizal networks is crucial for successful reforestation. Introducing appropriate mycorrhizal fungi to planting sites can significantly boost the survival and growth rates of newly planted trees, helping to establish a robust and resilient forest ecosystem more quickly. This advanced ecological insight underscores that reforestation is not just about planting trees, but about restoring an entire living system.

Challenges and Innovative Solutions in Reforestation

While the benefits are clear, reforestation efforts face numerous challenges. Climate change itself can make reforestation more difficult, with altered rainfall patterns and increased frequency of extreme weather events. Invasive species can outcompete native saplings, and securing long-term funding and community engagement are often hurdles.

However, innovative solutions are emerging. These include:

- Assisted Migration: Planting species that are predicted to thrive in future climates, rather than just current ones.

- Community-Based Reforestation: Empowering local communities to lead and benefit from reforestation projects, ensuring long-term stewardship.

- Technological Advancements: Using drones for mapping and seed dispersal, and advanced genetic selection for disease-resistant and climate-resilient trees.

- Agroforestry: Integrating trees into agricultural landscapes, providing both ecological benefits and economic returns for farmers.

Reforestation in Action: Global Examples

Across the globe, inspiring reforestation initiatives are demonstrating the power of collective action. The Great Green Wall initiative in Africa aims to combat desertification by planting a vast belt of trees across the Sahel region. In Costa Rica, decades of reforestation efforts have seen forest cover rebound significantly, demonstrating how a nation can reverse deforestation trends. Projects in the Amazon are working to restore degraded lands, bringing back vital rainforest ecosystems. These examples highlight that with dedication and scientific understanding, large-scale ecological restoration is not only possible but already underway.

A Greener Future Through Reforestation

Reforestation stands as a beacon of hope in the face of environmental degradation. It is a testament to nature’s resilience and humanity’s capacity for healing. By understanding the intricate science behind forest ecosystems, from the visible canopy to the hidden mycorrhizal networks, and by committing to thoughtful, sustained efforts, we can restore our planet’s vital green lungs. Every tree planted, every forest restored, contributes to a healthier climate, richer biodiversity, and a more sustainable future for all.