Understanding Habitat Fragmentation: A Silent Threat to Biodiversity

The natural world, once a vast tapestry of interconnected ecosystems, is increasingly being torn into smaller, isolated pieces. This profound alteration of landscapes, known as habitat fragmentation, stands as one of the most significant threats to biodiversity on our planet. It is a complex process driven primarily by human activities, transforming continuous natural areas into a mosaic of smaller patches, often surrounded by environments hostile to wildlife. Understanding fragmentation is crucial for anyone concerned about the future of Earth’s rich biological heritage.

What is Habitat Fragmentation?

At its core, habitat fragmentation describes the process by which a large, continuous habitat is divided into two or more smaller, isolated patches. Imagine a sprawling, unbroken forest. Over time, human development might carve roads through it, clear land for agriculture, or build towns within its borders. Each of these actions acts like a scissor, cutting the forest into smaller, disconnected islands of nature. These isolated patches are then surrounded by a “matrix” of human-dominated land, such as farms, cities, or industrial zones, which are often unsuitable for the species that once thrived in the original habitat.

This transformation is not merely about reducing the total amount of habitat, though that is a significant part of the problem. It is also about changing the spatial arrangement of what remains, creating barriers and altering the fundamental conditions for life within those remaining fragments.

The Mechanics of Fragmentation: Causes and Drivers

Habitat fragmentation is predominantly a byproduct of human expansion and development. Our ever-growing population and resource demands lead to a variety of activities that carve up natural landscapes.

- Agricultural Expansion: As global food demands rise, vast tracts of forests, grasslands, and wetlands are converted into farmland. This often involves clearing large areas, leaving behind fragmented remnants of the original ecosystem.

- Urbanization and Infrastructure Development: The growth of cities and towns directly consumes natural habitats. Furthermore, the construction of roads, highways, railways, and power lines to connect these urban centers acts as physical barriers, dissecting landscapes and severing ecological connections.

- Logging and Resource Extraction: While some logging practices can be sustainable, extensive clear-cutting or the creation of logging roads can rapidly fragment forests. Mining operations also contribute by creating large, disturbed areas that break up continuous habitats.

- Dams and Water Diversion: Large dams can flood vast areas, destroying terrestrial habitats, and alter river flows, fragmenting aquatic ecosystems and blocking fish migration routes.

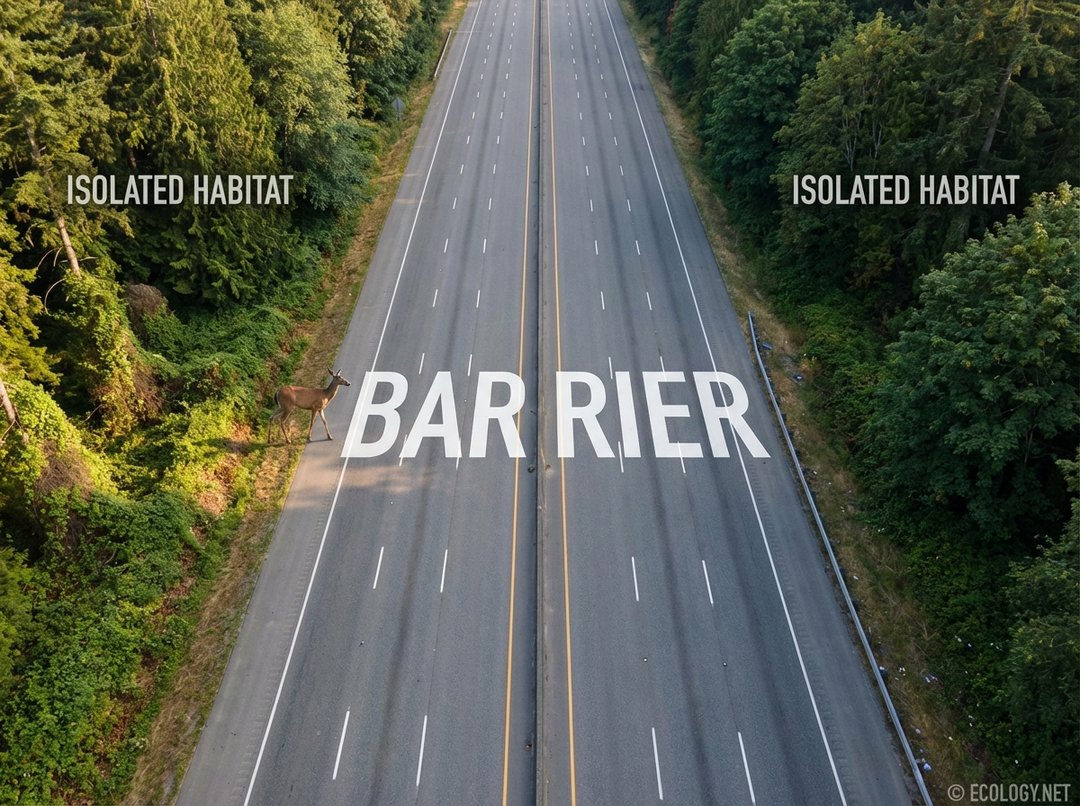

Consider the construction of a major highway through a pristine forest. This single act can instantly divide a habitat, creating an impassable barrier for many species and initiating a cascade of ecological changes.

Ecological Consequences: Why Fragmentation Matters

The division of habitats has far-reaching and often devastating consequences for biodiversity and ecosystem health. These impacts extend beyond the immediate loss of land, affecting species survival, genetic diversity, and ecosystem functions.

Loss of Habitat Area

The most obvious consequence is the direct reduction in the total amount of available habitat. Fewer resources, less space, and reduced breeding grounds mean that fewer individuals of a species can survive, making populations more vulnerable.

Increased Isolation

When habitats are fragmented, the remaining patches become isolated islands. This isolation makes it difficult or impossible for animals to move between patches to find mates, seek new food sources, or escape disturbances like fires or floods. For example, a population of forest birds might be trapped in a small woodlot, unable to reach another suitable forest just a few kilometers away due to urban development in between.

- Genetic Erosion: Isolated populations often experience reduced gene flow, leading to inbreeding and a loss of genetic diversity. This makes them less adaptable to environmental changes, diseases, or new threats.

- Reduced Recolonization: If a small, isolated population goes extinct in one fragment, it is much harder for individuals from other fragments to recolonize that area, leading to permanent local extinctions.

Edge Effects

Fragmentation dramatically increases the amount of “edge” habitat, the boundary between the natural fragment and the surrounding disturbed matrix. These edges are fundamentally different from the interior of a habitat and can have detrimental effects on species adapted to interior conditions.

- Altered Microclimates: Edges experience more sunlight, wind, and temperature fluctuations compared to the stable conditions of a forest interior. This can dry out the habitat, affecting moisture-sensitive plants and animals.

- Increased Predation and Parasitism: Predators and parasites often thrive along edges, where they can easily access both natural and human-modified environments. For instance, nest predation on forest birds can be significantly higher near forest edges.

- Invasive Species: Edges provide pathways for invasive plants and animals to penetrate natural habitats, outcompeting native species and disrupting ecological processes.

- Human Disturbance: Noise, light pollution, and human activity from the surrounding matrix can extend into the habitat fragments, disturbing wildlife.

Population Dynamics and Extinction Risk

Smaller, isolated populations within fragments are inherently more vulnerable to extinction. They are more susceptible to random events, such as disease outbreaks, severe weather, or demographic fluctuations (e.g., too many males, too few females). The concept of a “minimum viable population” highlights that a certain number of individuals are needed to ensure long-term survival, and fragmentation often pushes populations below this critical threshold.

Biodiversity Loss

Ultimately, all these consequences converge to accelerate biodiversity loss. Species that are highly specialized, have large home ranges, or are poor dispersers are particularly vulnerable. From the majestic Bengal tiger needing vast territories to the delicate orchids requiring specific forest conditions, fragmentation chips away at the very fabric of life.

Mitigating Fragmentation: Strategies for a Connected Future

While habitat fragmentation presents a formidable challenge, conservation scientists and practitioners are actively developing and implementing strategies to mitigate its impacts and foster a more connected future for wildlife.

Habitat Restoration and Reforestation

One direct approach is to restore degraded habitats or reforest areas that have been cleared. This can involve planting native vegetation, removing invasive species, and allowing natural processes to reclaim disturbed land. The goal is to enlarge existing fragments or create new ones, thereby increasing the total amount of available habitat.

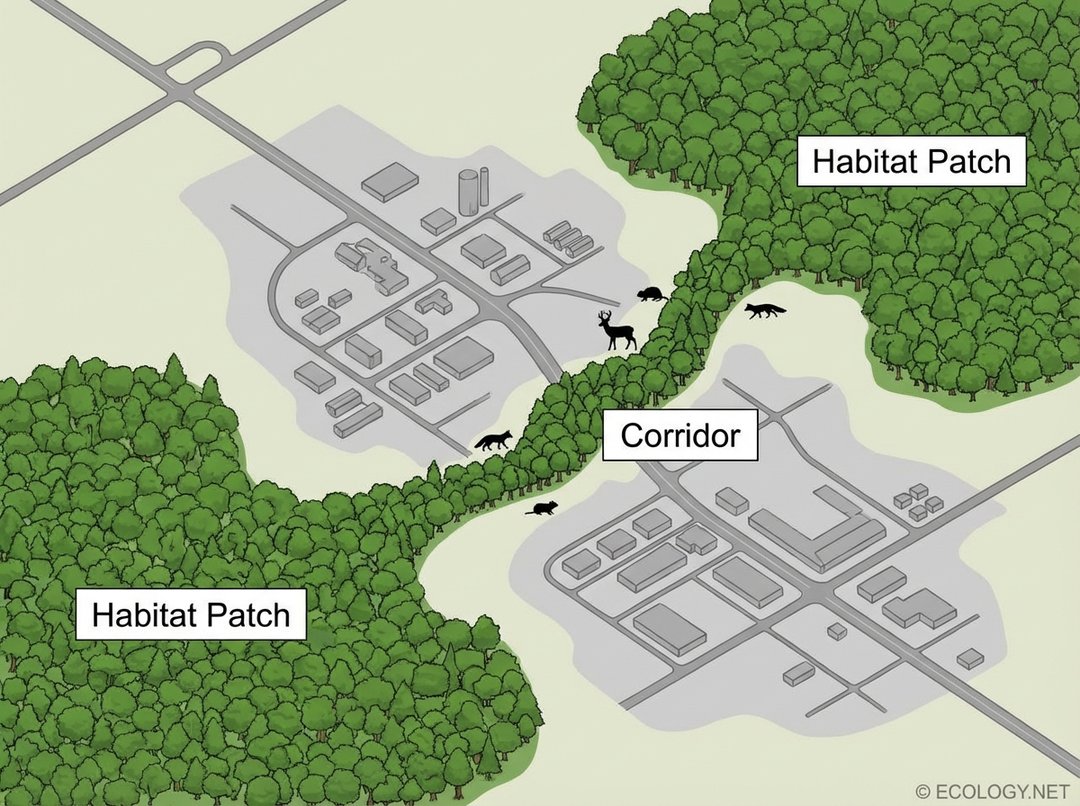

Habitat Corridors

Perhaps one of the most innovative and effective solutions is the establishment of habitat corridors. These are linear strips of natural habitat that connect isolated patches, allowing animals to move safely between them. Corridors can take many forms, from forested riverbanks to specially constructed wildlife bridges over highways.

By facilitating movement, corridors help to:

- Increase gene flow between populations, boosting genetic diversity.

- Allow species to access a wider range of resources, such as food and water.

- Enable animals to escape local disturbances or find new territories.

- Support the recolonization of areas where local extinctions have occurred.

Examples include “land bridges” built over busy roads in Banff National Park, Canada, or riparian corridors along rivers that connect forest fragments in agricultural landscapes.

Protected Areas and Buffer Zones

Establishing and effectively managing protected areas, such as national parks and wildlife reserves, is fundamental. These areas serve as core habitats. Creating buffer zones around these protected areas, where human activities are carefully managed to minimize disturbance, can help reduce edge effects and provide additional space for wildlife.

Sustainable Land Management

Integrating conservation into land use planning is critical. This includes promoting sustainable agriculture practices that minimize habitat conversion, encouraging responsible forestry that maintains forest connectivity, and designing urban areas with green spaces and wildlife-friendly infrastructure.

Policy and Legislation

Government policies and international agreements play a vital role in preventing further fragmentation and supporting mitigation efforts. Legislation protecting endangered species, regulating land use, and funding conservation initiatives are essential tools in the fight against habitat loss and fragmentation.

A Call for Connection

Habitat fragmentation is a stark reminder of humanity’s profound impact on the natural world. It transforms vibrant, interconnected ecosystems into isolated remnants, threatening countless species and diminishing the resilience of our planet. However, understanding this challenge also empowers us to act. Through thoughtful land use planning, dedicated conservation efforts, and innovative solutions like habitat corridors, we can work towards a future where nature is not just preserved in fragments, but reconnected and allowed to thrive. The health of our planet, and indeed our own well-being, depends on our ability to mend the broken landscape and foster a world where all life can move freely and flourish.