Life on Earth is a tapestry woven with countless interactions, some harmonious, others fiercely competitive. Among the most intricate and often unsettling of these relationships is parasitism. Far from being a mere footnote in the grand narrative of nature, parasites are master strategists, shaping ecosystems, driving evolution, and influencing the very fabric of life in ways that are both profound and pervasive.

Understanding Parasitism: A Fundamental Ecological Relationship

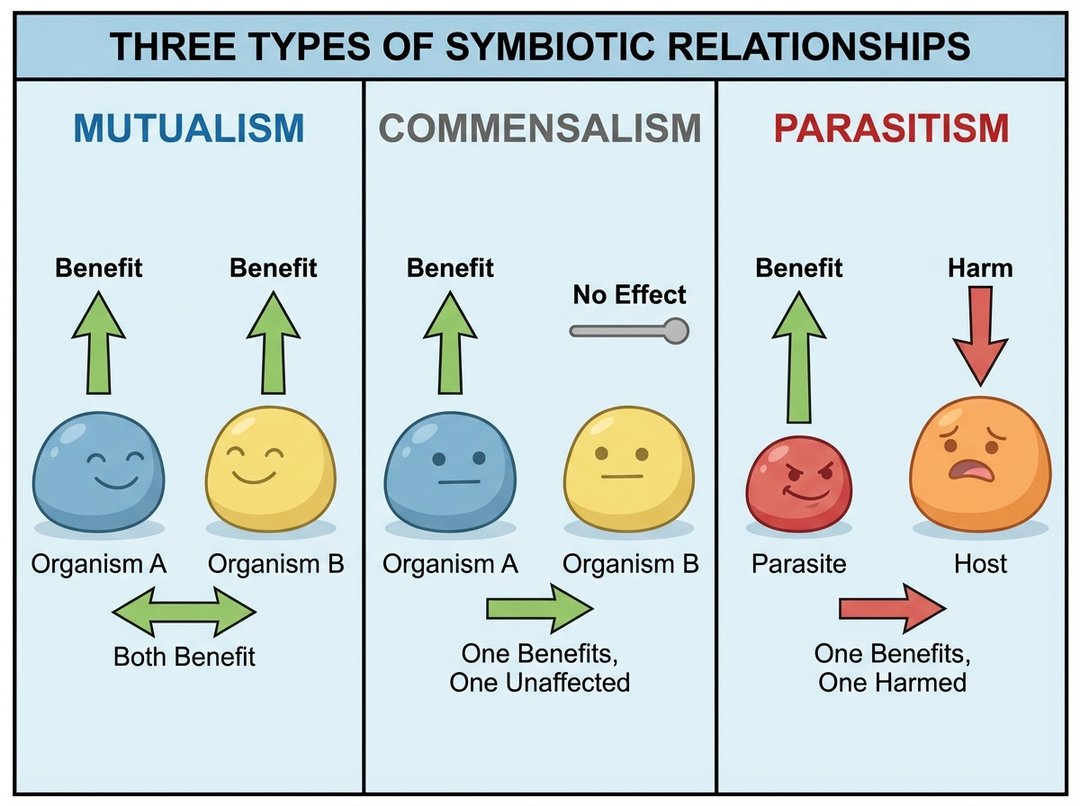

At its core, parasitism is a type of symbiotic relationship, an intimate and prolonged interaction between two different biological organisms. However, unlike the mutually beneficial dance of mutualism or the one-sided neutrality of commensalism, parasitism involves a clear imbalance. In this dynamic, one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host, which is harmed.

Consider the spectrum of symbiotic relationships:

- Mutualism: Both organisms benefit from the interaction. A classic example is the relationship between bees and flowers, where bees get nectar and flowers are pollinated.

- Commensalism: One organism benefits, while the other is neither significantly harmed nor helped. Remoras attaching to sharks for transport and scraps of food exemplify this.

- Parasitism: The parasite benefits, and the host is harmed. This harm can range from mild inconvenience to severe disease and even death.

The relationship between parasite and host is often a finely tuned evolutionary arms race. Parasites evolve to exploit their hosts more effectively, while hosts develop defenses to resist parasitic invasion and mitigate damage. This ongoing struggle drives significant evolutionary change in both parties.

The Diverse World of Parasites: Where Do They Reside?

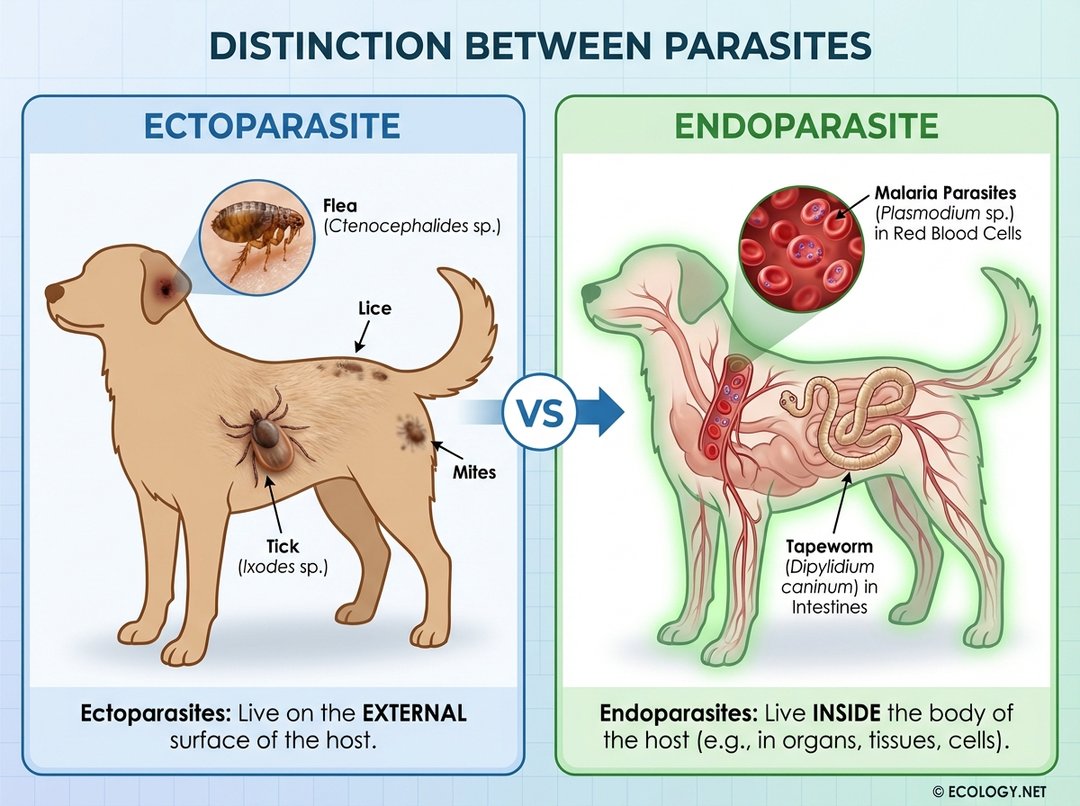

Parasites are incredibly diverse, inhabiting nearly every niche imaginable and affecting virtually all forms of life, from microscopic bacteria to colossal whales. One fundamental way to categorize them is by their location relative to the host’s body.

Ectoparasites: Living on the Outside

Ectoparasites are those that live on the external surface of their host. They typically feed on the host’s skin, blood, or other bodily fluids. Their presence is often visible and can cause irritation, skin lesions, or transmit diseases.

- Fleas and Ticks: These notorious blood-feeders are common ectoparasites of mammals and birds. They can cause itching, anemia, and are vectors for serious diseases like Lyme disease (ticks) or plague (fleas).

- Lice: Found on the hair or feathers of their hosts, lice feed on skin flakes, blood, or sebaceous secretions, leading to discomfort and sometimes secondary infections.

- Leeches: Aquatic ectoparasites that attach to the skin of vertebrates, including humans, to feed on blood.

Endoparasites: Inhabiting the Interior

Endoparasites, in contrast, live inside the host’s body. Their internal residence often makes them more challenging to detect and treat. They can inhabit various organs and tissues, from the digestive tract to the bloodstream, muscles, and even the brain.

- Intestinal Worms: Tapeworms, roundworms, and hookworms are common endoparasites that reside in the digestive system, absorbing nutrients directly from the host’s food or tissues. They can cause malnutrition, abdominal pain, and other gastrointestinal issues.

- Malaria Parasites (Plasmodium): These microscopic protozoans are transmitted by mosquitoes and infect red blood cells and liver cells in humans, causing the debilitating disease malaria.

- Flukes: A diverse group of flatworms that can infect various organs, including the liver, lungs, and blood vessels, often causing chronic inflammation and organ damage.

Strategies of Survival: The Ingenuity of Parasites

Parasites have evolved an astonishing array of strategies to locate hosts, evade immune responses, reproduce, and ensure transmission to new hosts. These strategies highlight the incredible adaptability of life.

Nutritional Exploitation

The most straightforward parasitic strategy involves directly consuming the host’s resources. Intestinal worms, for instance, simply absorb digested food from the host’s gut. Plant parasites, like mistletoe, tap into the vascular system of their host trees to draw water and nutrients, weakening the host over time.

Reproductive Manipulation

Some parasites manipulate their host’s reproductive efforts for their own benefit. Brood parasites, such as cuckoo birds, lay their eggs in the nests of other bird species, tricking the unwitting host parents into raising the cuckoo chicks. The cuckoo chick often outcompetes or even ejects the host’s own offspring, ensuring its survival at the complete expense of the host’s reproductive success.

Behavioral Control: The Ultimate Manipulation

Perhaps the most chilling and fascinating parasitic strategies involve the manipulation of host behavior. Some parasites can hijack the host’s nervous system, altering its actions in ways that benefit the parasite’s life cycle, often by facilitating transmission to the next host.

The intricate dance between parasite and host is a testament to evolution’s creative power, where survival often hinges on cunning and adaptation.

A remarkable example is the “zombie ant” phenomenon. The fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis infects carpenter ants. Once infected, the fungus manipulates the ant’s behavior, compelling it to leave its nest, climb a plant stem, and bite onto the underside of a leaf or twig. The ant then dies, locked in place, and the fungus sprouts a fruiting body from the ant’s head, releasing spores to infect more ants below. This precise, fatal manipulation ensures the fungus disperses its spores from an optimal location.

Another example involves horsehair worms. These parasites develop inside insects like crickets. When mature, the worm induces the cricket to seek out water, where the cricket drowns, allowing the adult worm to emerge and reproduce in an aquatic environment.

Hyperparasitism: Parasites of Parasites

The complexity of parasitic relationships extends even further with hyperparasitism, where a parasite itself is host to another parasite. This creates intricate food webs within parasitic interactions. For instance, some wasps are parasitic on other insects, but these parasitic wasps can, in turn, be parasitized by even smaller hyperparasitic wasps.

The Impact of Parasitism: From Individuals to Ecosystems

The effects of parasitism ripple through all levels of biological organization, from the health of individual organisms to the dynamics of entire ecosystems.

On Individual Hosts

For an individual host, the impact of a parasite can range from mild discomfort to severe disease, reduced reproductive success, and even death. Parasites can:

- Deplete host resources, leading to malnutrition or anemia.

- Damage tissues and organs, impairing function.

- Weaken the host’s immune system, making it susceptible to other infections.

- Alter host behavior, increasing its vulnerability to predators or environmental stressors.

On Populations and Ecosystems

At a broader scale, parasites play crucial ecological roles:

- Population Regulation: Parasites can limit the size of host populations, preventing overpopulation and maintaining ecological balance. For example, outbreaks of disease caused by parasites can decimate animal populations.

- Driving Natural Selection: The constant pressure from parasites drives the evolution of host resistance, while hosts, in turn, select for more virulent or evasive parasites. This co-evolutionary arms race is a powerful engine of biodiversity.

- Maintaining Biodiversity: By selectively weakening or killing dominant host species, parasites can prevent a single species from outcompeting others, thereby promoting species diversity within an ecosystem.

- Food Web Dynamics: Parasites can alter food web structures by changing the behavior or survival rates of their hosts, influencing predator-prey relationships and energy flow.

The Evolutionary Dance: A Co-evolutionary Arms Race

The relationship between a parasite and its host is rarely static. Instead, it is a dynamic, ongoing evolutionary struggle known as co-evolution. Hosts evolve defenses to resist parasites, such as immune responses, behavioral avoidance, or physical barriers. In response, parasites evolve counter-adaptations to overcome these defenses, such as immune evasion mechanisms, novel infection strategies, or increased virulence.

This perpetual arms race is often described by the Red Queen Hypothesis, which states that organisms must constantly evolve, not just to gain reproductive advantage, but also simply to survive against ever-evolving opposing organisms in an ever-changing environment. For parasites and hosts, this means running as fast as they can just to stay in the same place, locked in an endless cycle of adaptation and counter-adaptation.

Conclusion

Parasitism is a ubiquitous and fundamental force in nature, a testament to life’s relentless drive to survive and reproduce. From the microscopic world of viruses and bacteria to the macroscopic realm of tapeworms and ticks, parasites demonstrate an astonishing diversity of forms and strategies. They are not merely agents of disease but integral components of ecosystems, shaping biodiversity, driving evolution, and maintaining ecological balance.

Understanding parasitism offers profound insights into the interconnectedness of life and the intricate evolutionary processes that have sculpted the natural world. It reminds us that even in relationships defined by exploitation, there is an underlying complexity and a delicate balance that continues to fascinate and challenge scientific inquiry.