Life on Earth is a tapestry woven with countless interactions. From the smallest bacteria to the largest whales, no organism exists in isolation. These intricate connections, where two or more different species live in close physical association, are collectively known as symbiosis. Far from being a simple concept, symbiosis encompasses a spectrum of relationships, each with profound implications for the survival, evolution, and diversity of life itself.

Understanding symbiosis is fundamental to grasping how ecosystems function and how life has evolved over billions of years. It reveals a world where cooperation, exploitation, and coexistence are not just possibilities, but essential strategies for thriving.

The Spectrum of Symbiotic Relationships

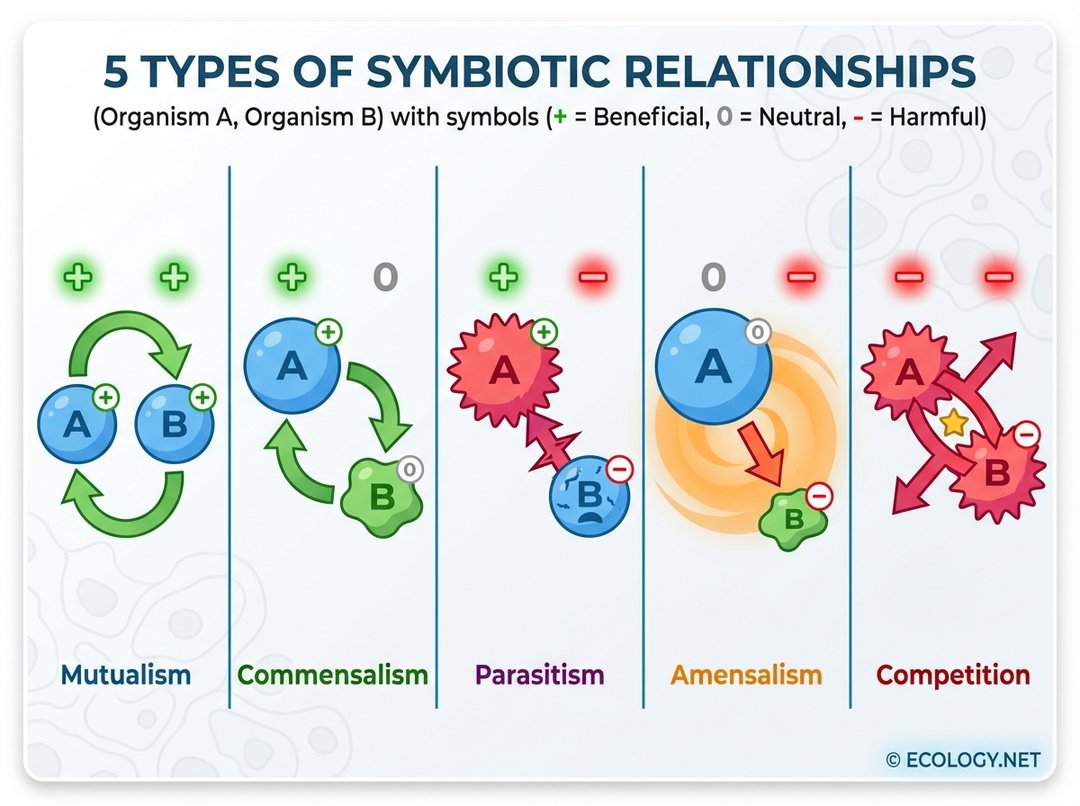

Symbiosis is not a single type of interaction, but rather a broad umbrella term covering several distinct categories, defined by the outcome for each participating species. Ecologists typically categorize these relationships based on whether each partner benefits (+), is harmed (-), or is unaffected (0).

Let us explore these fundamental types:

Mutualism: A Win-Win Partnership

Perhaps the most celebrated form of symbiosis, mutualism occurs when both interacting species benefit from the relationship (+/+). These partnerships are often critical for the survival of both parties, leading to co-evolutionary adaptations that strengthen the bond.

- Pollination: Bees visiting flowers are a classic example. The bee gains nectar (food), and the flower gets its pollen transferred, enabling reproduction.

- Mycorrhizal Fungi: These fungi form associations with plant roots. The fungi extend the plant’s root system, enhancing water and nutrient absorption, while the plant provides the fungi with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis.

- Lichens: A fascinating example where a fungus and an alga (or cyanobacterium) live together. The alga provides food through photosynthesis, and the fungus provides protection, moisture, and minerals.

One of the most visually striking examples of mutualism in action can be found beneath the ocean waves: cleaning symbiosis.

In this remarkable interaction, smaller cleaner fish or shrimp set up “cleaning stations” on coral reefs. Larger predatory fish, like groupers or moray eels, will approach these stations and allow the cleaners to remove parasites, dead skin, and debris from their bodies, even from inside their mouths and gills. The cleaner gets a meal, and the larger fish benefits from improved health and hygiene. It is a testament to the power of cooperation in even the most competitive environments.

Commensalism: One Benefits, the Other is Unaffected

In commensalism, one species benefits, while the other is neither helped nor harmed (+/0). This relationship can be subtle and often involves one species using another for shelter, transport, or food scraps without significantly impacting the host.

- Barnacles on Whales: Barnacles attach to the skin of whales, gaining a mobile home and access to nutrient-rich waters as the whale swims. The whale, being massive, is generally unaffected by the presence of the barnacles.

- Cattle Egrets and Grazing Animals: Egrets follow cattle or other large grazing animals, feeding on insects stirred up by the animals’ movements. The cattle are neither helped nor harmed by the egrets’ presence.

- Remoras and Sharks: Remora fish attach themselves to sharks, feeding on leftover food scraps from the shark’s meals and gaining protection and transport. The shark is largely indifferent to the remora.

Parasitism: One Benefits, the Other is Harmed

Parasitism is a relationship where one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of another, the host (+/-). Parasites typically live on or in their host, deriving nutrients and often causing harm, though rarely immediate death, as their survival depends on the host’s continued existence.

- Ticks and Mammals: Ticks attach to mammals, feeding on their blood. The tick gains nourishment, while the mammal can suffer from blood loss, irritation, and potential disease transmission.

- Tapeworms in Intestines: Tapeworms live inside the digestive tracts of animals, absorbing nutrients directly from the host’s food. This can lead to malnutrition and other health issues for the host.

- Mistletoe on Trees: Mistletoe is a parasitic plant that grows on trees, drawing water and nutrients from the host tree, which can weaken or stress the tree.

Amensalism: One is Harmed, the Other is Unaffected

Amensalism is a less common and often overlooked symbiotic relationship where one species is harmed, and the other is unaffected (0/-). This typically occurs when one organism produces a substance or creates a condition that is detrimental to another, without gaining any benefit itself.

- Penicillin Mold: The classic example involves the mold Penicillium producing penicillin, an antibiotic that inhibits the growth of certain bacteria. The mold itself does not directly benefit from the bacteria’s harm in this context, though it clears competition.

- Large Trees Shading Undergrowth: A large tree can cast a dense shadow, preventing smaller plants from growing beneath it due to lack of sunlight. The tree is unaffected by the absence of the smaller plants, but the smaller plants are harmed.

Competition: A Lose-Lose Scenario

While often considered a separate ecological interaction, competition can also be viewed within the framework of symbiosis when species are in close association and vying for the same limited resources. In this relationship, both species are negatively affected (-/-) as they expend energy and resources to outcompete each other.

- Plants Competing for Light: Different plant species in a forest may compete for access to sunlight, leading to reduced growth or survival for less successful competitors.

- Predators Competing for Prey: Two different predator species, such as lions and hyenas, may compete for the same antelope prey, leading to reduced food availability for both.

The Profound Impact: Endosymbiosis and the Evolution of Life

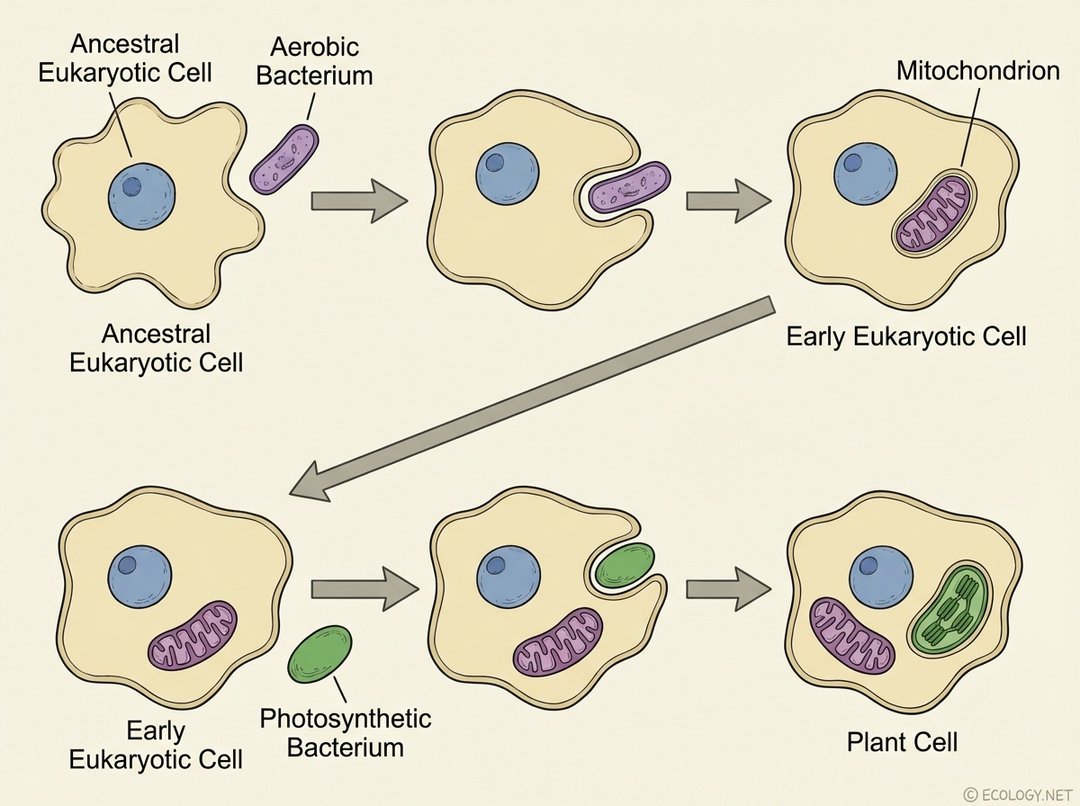

Beyond the daily interactions we observe, symbiosis has played an unimaginably crucial role in shaping life on Earth. One of the most revolutionary concepts in biology, the Theory of Endosymbiosis, posits that some of the most fundamental components of eukaryotic cells, the cells that make up plants, animals, fungi, and protists, originated from symbiotic relationships.

This theory suggests that billions of years ago, a large ancestral eukaryotic cell engulfed smaller prokaryotic cells (like bacteria) but did not digest them. Instead, these smaller cells continued to live and function within the larger cell, eventually evolving into organelles. The most famous examples are:

- Mitochondria: These powerhouses of the cell, responsible for generating energy, are believed to have evolved from aerobic bacteria that were engulfed by an ancestral eukaryotic cell. Over time, this mutualistic relationship became obligate, meaning neither could survive independently.

- Chloroplasts: In a later event, some early eukaryotic cells that already contained mitochondria are thought to have engulfed photosynthetic bacteria (similar to cyanobacteria). These bacteria then evolved into chloroplasts, the organelles responsible for photosynthesis in plant cells and algae.

The evidence for endosymbiosis is compelling: mitochondria and chloroplasts have their own circular DNA, reproduce independently within the cell, and have double membranes, consistent with an engulfment event. This ancient symbiotic event was a turning point in evolution, paving the way for the complexity and diversity of eukaryotic life we see today.

Symbiosis in Broader Ecosystems and Human Life

The principles of symbiosis extend far beyond microscopic origins and dramatic ocean scenes. They are woven into the fabric of every ecosystem and even our own bodies.

- Human Microbiome: Our digestive tracts are home to trillions of bacteria, forming a complex mutualistic relationship. These microbes help us digest food, synthesize vitamins, and protect against harmful pathogens.

- Coral Reefs: The vibrant colors of coral reefs are largely due to a mutualistic relationship between coral polyps and microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. The algae live within the coral tissue, providing food through photosynthesis, while the coral provides a protected environment and compounds for photosynthesis.

- Nitrogen Fixation: Leguminous plants (like peas and beans) form mutualistic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria in their root nodules. The bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by the plant, while the plant provides the bacteria with carbohydrates.

These examples highlight that symbiosis is not just an interesting biological phenomenon, but a fundamental ecological process that drives nutrient cycling, shapes biodiversity, and underpins the stability of ecosystems worldwide.

Conclusion: The Interconnected Web of Life

From the microscopic origins of our cells to the vast networks of life in a rainforest, symbiosis is an omnipresent force. It demonstrates that life is not a solitary endeavor, but a grand, interconnected web of interactions where species constantly influence each other’s fates. Whether through cooperation, exploitation, or mere coexistence, these relationships drive evolution, build ecosystems, and ultimately define the very nature of life on Earth. Recognizing the power of symbiosis allows for a deeper appreciation of the intricate balance and profound interdependence that characterize our planet’s living systems.