In the grand theater of life, where vibrant plants reach for the sun and diverse animals roam, there exists a silent, tireless workforce operating beneath our feet and within every fallen leaf. These are the decomposers, the unsung heroes of every ecosystem, responsible for the crucial task of recycling life’s building blocks. Without them, our world would be buried under mountains of dead organic matter, and the essential nutrients that sustain all life would remain locked away, inaccessible.

Decomposers are the ultimate recyclers, transforming the remnants of once-living organisms back into the fundamental elements that fuel new growth. They are the bridge between death and new life, ensuring the continuous flow of energy and matter through our planet’s intricate ecological webs. Understanding their roles and processes is not just a matter of scientific curiosity, but a key to appreciating the delicate balance that sustains all living things.

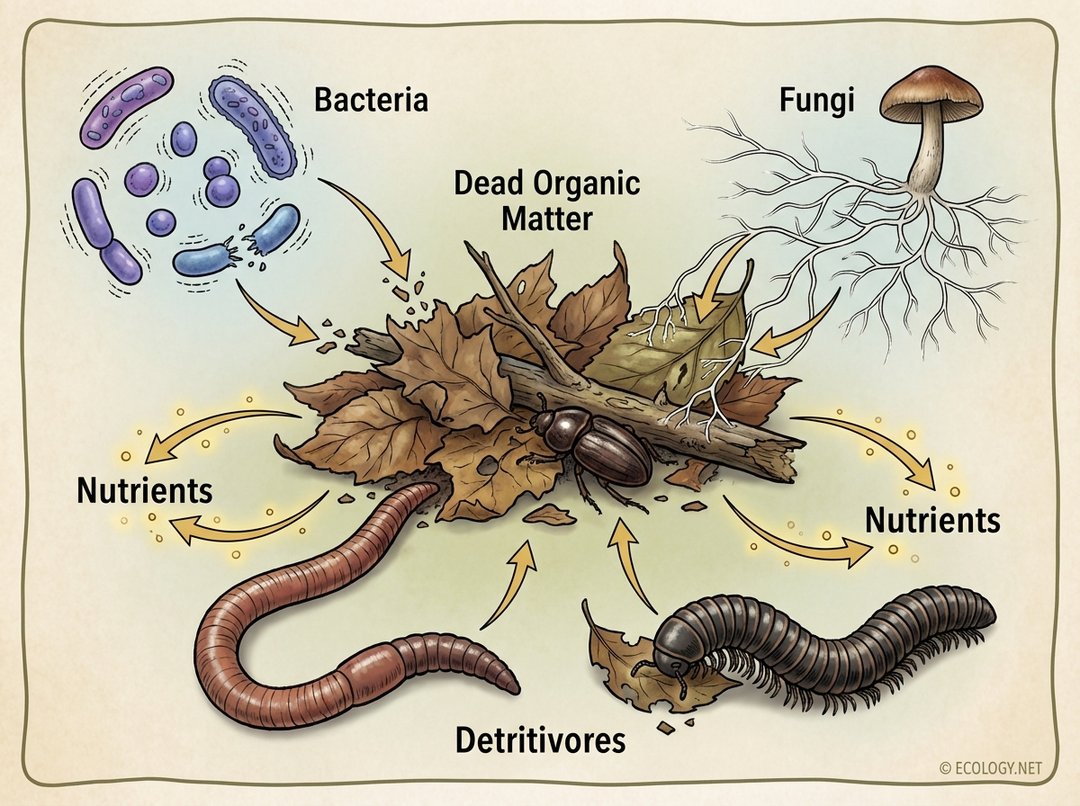

The Major Players: Bacteria, Fungi, and Detritivores

Decomposition is not a solitary act but a collaborative effort involving a diverse community of organisms. While often lumped together, these decomposers can be broadly categorized into three primary groups, each with a specialized role in breaking down organic matter.

Bacteria: The Microscopic Powerhouses

These single-celled microorganisms are ubiquitous, found in virtually every environment on Earth. In the context of decomposition, bacteria are incredibly versatile, capable of breaking down a vast array of complex organic compounds. They thrive in diverse conditions, from oxygen-rich soils to anaerobic swamps, utilizing enzymes to chemically dismantle dead plant and animal tissues. Their sheer numbers and rapid reproduction rates make them formidable agents of decay, especially in the early stages of decomposition and in environments where other decomposers might struggle.

- Examples: Bacillus species, various anaerobic bacteria in wetlands.

- Role: Primary chemical breakdown of complex organic molecules into simpler forms.

Fungi: The Master Chemists of the Soil

Fungi, including molds, yeasts, and mushrooms, are distinguished by their filamentous structures called hyphae. These hyphae grow into and through dead organic matter, secreting powerful digestive enzymes externally. These enzymes break down tough materials like cellulose and lignin, which are major components of plant cell walls and are often resistant to bacterial action. Fungi are particularly crucial in forest ecosystems, where they decompose fallen logs and leaf litter, making nutrients available for trees.

- Examples: Shelf fungi on dead trees, various molds on decaying fruit, mycorrhizal fungi associated with plant roots.

- Role: Breaking down recalcitrant organic compounds, especially plant structural components.

Detritivores: The Physical Processors

Unlike bacteria and fungi, detritivores are macroscopic organisms that physically consume and break down dead organic matter. They fragment larger pieces into smaller ones, increasing the surface area for microbial action. This mechanical breakdown is a vital first step in many decomposition pathways, accelerating the overall process. Their digestive systems also further process the material, often releasing nutrients in their waste products.

- Examples:

- Earthworms: Ingest soil and organic matter, aerating the soil and mixing nutrients.

- Millipedes: Feed on decaying plant material, especially leaf litter.

- Springtails and Mites: Tiny arthropods that graze on fungi and detritus.

- Dung Beetles: Specialize in breaking down animal waste.

- Role: Physical fragmentation, aeration, and initial digestion of organic matter.

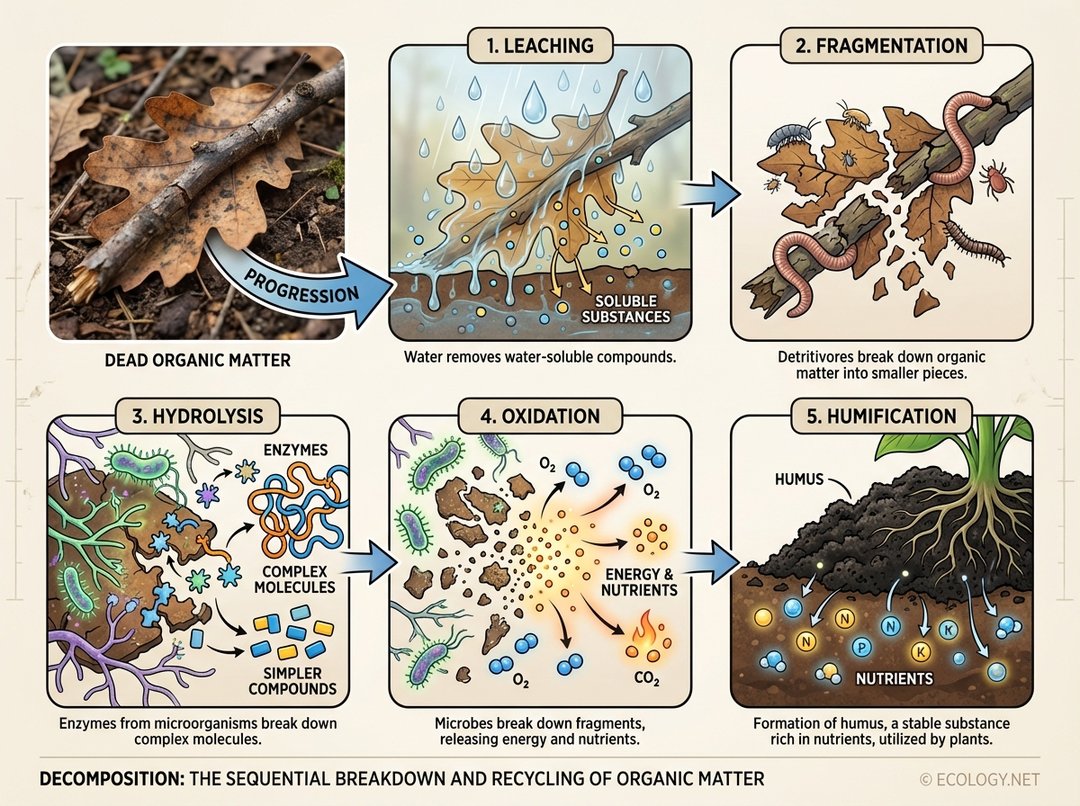

The Decomposition Process: A Step-by-Step Look

Decomposition is not a single event but a complex, sequential process involving multiple stages. From a fresh carcass or fallen leaf to rich, dark soil, the journey is a fascinating transformation orchestrated by the decomposer community.

Here is a breakdown of the typical steps involved:

- Leaching: This initial stage involves the physical removal of soluble compounds from dead organic matter by water. Rainwater, for instance, can wash away sugars, amino acids, and other water-soluble nutrients from fallen leaves or dead animals. While not directly involving decomposers, leaching makes these nutrients immediately available in the soil or water, where they can be taken up by plants or microorganisms.

- Fragmentation: This is where detritivores play a starring role. Organisms like earthworms, millipedes, and termites physically break down larger pieces of dead organic matter into smaller fragments. Imagine a fallen tree branch being chewed by insects or leaves being shredded by soil invertebrates. This process significantly increases the surface area of the material, making it much more accessible for microbial attack.

- Hydrolysis: Once fragmented, the smaller pieces become targets for bacteria and fungi. These microorganisms secrete extracellular enzymes that break down complex organic polymers (like cellulose, lignin, and proteins) into simpler monomers (like sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids). This chemical breakdown, often involving the addition of water molecules, is crucial for unlocking the energy and nutrients stored within the organic matter.

- Oxidation: Following hydrolysis, the simpler organic molecules are further broken down by microorganisms through metabolic processes, often involving oxygen. This stage releases energy for the decomposers themselves and liberates inorganic nutrients such as nitrates, phosphates, and sulfates into the environment. Carbon dioxide is also released into the atmosphere as carbon compounds are oxidized.

- Humification: Not all organic matter is completely broken down. Some resistant compounds, particularly those derived from lignin, are transformed into a stable, dark, amorphous substance called humus. Humus is a vital component of healthy soil, improving its structure, water retention capacity, and nutrient-holding ability. It represents the long-term storage of carbon and nutrients in the soil, slowly releasing them over time.

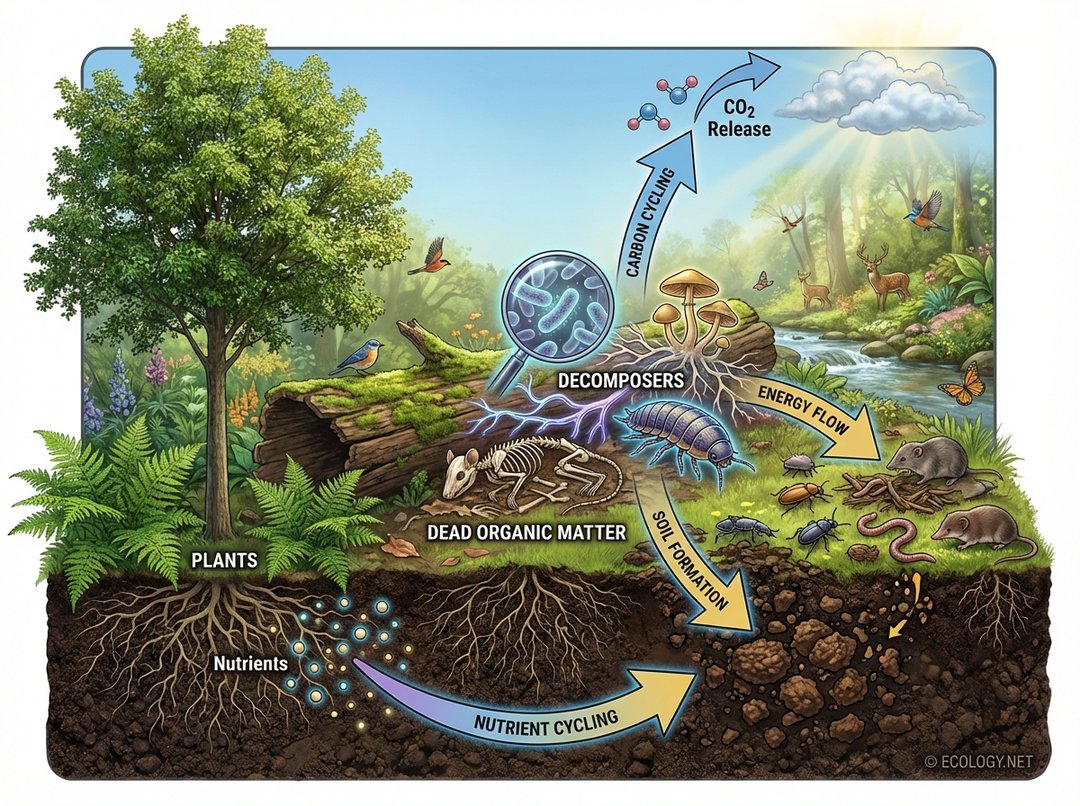

Why Are Decomposers Important? The Ecological Role

The work of decomposers extends far beyond simply cleaning up dead material. Their activities are fundamental to the functioning and health of every ecosystem on Earth. Without them, the intricate cycles that sustain life would grind to a halt.

Nutrient Cycling: The Circle of Life

Perhaps the most critical role of decomposers is their contribution to nutrient cycling. All living organisms require a steady supply of nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to grow and reproduce. When organisms die, these essential nutrients are locked within their tissues. Decomposers break down these tissues, releasing the inorganic forms of these nutrients back into the soil or water, where they can be reabsorbed by plants. This continuous recycling ensures that nutrients are not permanently lost but are constantly made available for new generations of life. Imagine a forest where nutrients are never returned to the soil; eventually, the soil would become barren, unable to support plant growth.

Soil Formation and Health: The Foundation of Terrestrial Life

Decomposers are the architects of healthy soil. Through their activities, they break down organic matter, contributing to the formation of humus. Humus improves soil structure, making it more porous and better able to retain water and air. It also increases the soil’s cation exchange capacity, meaning its ability to hold onto and supply essential plant nutrients. The physical actions of detritivores, like earthworms burrowing, further aerate the soil and mix organic matter, enhancing its fertility and supporting a thriving microbial community.

Carbon Cycling: Regulating Earth’s Climate

Decomposers play a significant role in the global carbon cycle. As they break down organic matter, they respire, releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere. This CO2 can then be taken up by plants during photosynthesis, completing a vital loop. While decomposition releases carbon, it also contributes to the formation of stable humus, which stores carbon in the soil for long periods. The balance between carbon release and carbon sequestration by decomposers is crucial for regulating atmospheric CO2 levels and, consequently, Earth’s climate.

Energy Flow: Fueling the Food Web

While often overlooked, decomposers are an integral part of the energy flow within an ecosystem. The energy stored in dead organic matter is not lost; it is transferred to the decomposer community. Bacteria, fungi, and detritivores derive their energy from breaking down this material. In turn, these decomposers themselves become a food source for other organisms, such as mites, nematodes, and even some birds and mammals. This forms a detrital food web, running parallel to the grazing food web, ensuring that energy continues to move through the ecosystem.

Beyond the Basics: Factors Influencing Decomposition

The rate at which decomposition occurs is not uniform across all environments. Several key factors can significantly influence how quickly decomposers break down organic matter.

- Temperature: Generally, warmer temperatures accelerate decomposition rates because microbial activity increases with heat. However, extremely high temperatures can denature enzymes and inhibit decomposers, while freezing temperatures halt activity. Think of how food spoils faster on a warm counter than in a refrigerator.

- Moisture: Water is essential for decomposer activity. It facilitates the transport of enzymes and nutrients and is a reactant in many biochemical processes. Too little moisture (drought conditions) can severely limit decomposition, while too much moisture (waterlogged conditions) can create anaerobic environments, favoring slower-acting anaerobic bacteria and inhibiting many fungi and detritivores.

- Oxygen Availability: Most efficient decomposition is aerobic, meaning it requires oxygen. Fungi and many bacteria thrive in oxygen-rich environments. In anaerobic conditions, such as deep in bogs or sediments, decomposition is much slower and often leads to the accumulation of organic matter, like peat.

- Substrate Quality: The type of organic matter itself plays a huge role.

- Easily decomposable materials: Sugars, starches, and proteins break down quickly.

- Moderately decomposable materials: Cellulose and hemicellulose (found in plant cell walls) take longer.

- Recalcitrant materials: Lignin (the tough woody component of plants) and chitin (found in insect exoskeletons and fungal cell walls) are very resistant and decompose slowly.

- pH: The acidity or alkalinity of the environment can affect which decomposers are most active. Many bacteria prefer neutral pH, while some fungi can tolerate more acidic conditions.

Decomposers in Action: Real-World Examples

To truly appreciate the work of decomposers, it helps to see them in various ecological settings:

- Forest Floors: Every autumn, forests are blanketed with fallen leaves, twigs, and dead branches. Within months, sometimes weeks, this litter begins to disappear, thanks to the combined efforts of earthworms, millipedes, springtails, fungi, and bacteria. They transform the leaf litter into rich, dark soil, releasing nutrients for the next season’s growth.

- Ocean Depths: Even in the abyssal plains of the ocean, far from sunlight, decomposers are at work. When marine organisms die, their bodies sink to the seafloor, forming “marine snow.” Specialized bacteria and fungi, often adapted to extreme pressures and cold temperatures, break down this organic matter, recycling nutrients in the deep ocean.

- Compost Piles: A backyard compost pile is a perfect microcosm of decomposition. By layering organic waste like kitchen scraps and yard trimmings, and maintaining optimal moisture and aeration, we create an ideal environment for bacteria, fungi, and detritivores (like worms and insects) to rapidly convert waste into nutrient-rich compost for gardens.

- Animal Carcasses: The decomposition of a large animal carcass is a dramatic example. Scavengers like vultures and coyotes might initiate the process, but soon, a succession of insects (like blowflies and carrion beetles) and a vast array of bacteria and fungi take over, reducing the body to bones and eventually integrating even those into the soil.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Recyclers

Decomposers, though often unseen and uncelebrated, are the bedrock of ecological stability. They are the diligent housekeepers of our planet, ensuring that nothing goes to waste and that the essential ingredients for life are continuously circulated. From the smallest bacterium to the largest earthworm, each plays a vital role in transforming death into life, maintaining soil fertility, regulating global cycles, and ultimately, sustaining the intricate web of existence. Understanding and appreciating these tireless workers is key to grasping the fundamental processes that govern our natural world and to fostering healthy, resilient ecosystems for generations to come.