In the intricate dance of nature and human endeavor, few concepts hold as much profound importance as “yield stability.” It is a term that resonates across fields, from the quiet hum of an apple orchard to the complex dynamics of global food systems and the resilience of entire ecosystems. While the pursuit of high yields often dominates headlines, the steadfastness and predictability of those yields are arguably just as, if not more, critical for long-term sustainability and well-being.

Imagine a world where harvests are consistently abundant, where ecosystems reliably provide their services, and where the future feels a little less uncertain. This is the promise of yield stability, a concept that moves beyond mere quantity to embrace the crucial element of consistency. It is about building systems that can weather storms, adapt to change, and continue to deliver, year after year.

What Exactly Is Yield Stability?

At its core, yield stability refers to the consistency of output over time, despite environmental fluctuations or other challenges. It is not simply about achieving the highest possible yield in a single season, but rather about minimizing the variability of yield across multiple seasons or years. A system with high yield stability produces a predictable amount, even if that amount is not always the absolute maximum achievable in ideal conditions.

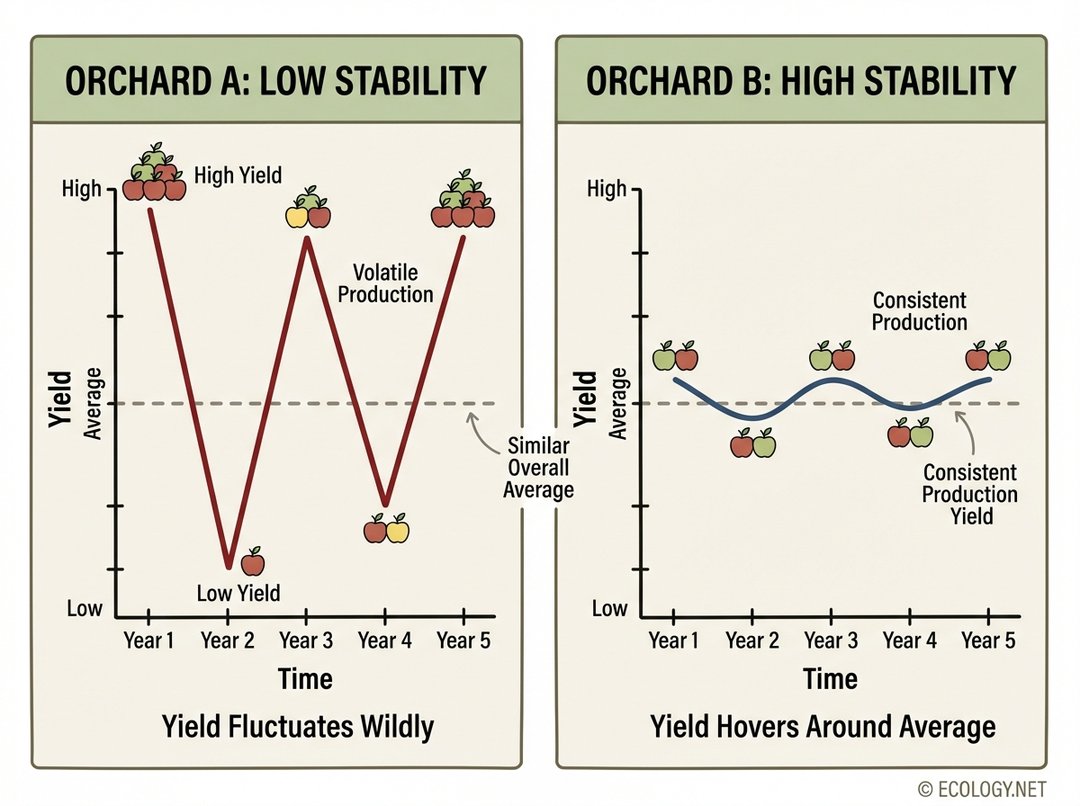

Consider two apple orchards. Orchard A might have a phenomenal harvest one year, followed by a disastrous one the next, then an average one. Orchard B, on the other hand, consistently produces a good, steady harvest every year. While Orchard A might occasionally boast a higher peak yield, Orchard B offers far greater reliability and predictability. This consistency is the hallmark of yield stability.

This distinction is vital. A high average yield can mask significant instability, leading to periods of surplus followed by scarcity. True resilience lies in the ability to maintain a reliable output, providing a buffer against unforeseen circumstances and ensuring continuous provision.

Why Does Yield Stability Matter?

The implications of yield stability stretch far and wide, touching upon fundamental aspects of human society and ecological health.

- Food Security: For agricultural systems, stable yields are paramount for ensuring consistent food supplies. Erratic harvests can lead to price volatility, food shortages, and increased vulnerability for communities, particularly in regions prone to environmental stressors.

- Economic Stability: Farmers and agricultural businesses rely on predictable yields for their livelihoods. Stable production allows for better planning, investment, and risk management, fostering economic resilience within rural communities.

- Ecosystem Resilience: In natural ecosystems, stability refers to the ability of a system to resist disturbance and recover from it. Stable ecosystems are more robust against climate change, invasive species, and other environmental pressures, continuing to provide essential services like clean water, air, and pollination.

- Resource Management: Predictable yields enable more efficient and sustainable management of resources such as water, land, and nutrients. When yields fluctuate wildly, it can lead to over-extraction during lean times or waste during periods of unexpected abundance.

- Long-term Sustainability: Focusing on yield stability encourages practices that build long-term health into agricultural and natural systems, rather than short-term gains that might deplete resources or degrade the environment.

Factors Influencing Yield Stability

Many elements contribute to or detract from yield stability, ranging from broad environmental conditions to specific ecological characteristics and human management choices.

Environmental Factors

- Climate Variability: Unpredictable weather patterns, including droughts, floods, heatwaves, and late frosts, are major drivers of yield instability. Regions experiencing increased climate variability often face the greatest challenges in maintaining consistent production.

- Soil Health: Healthy soil, rich in organic matter, has better water retention capabilities and nutrient cycling, making crops more resilient to dry spells or heavy rains. Degraded soils, conversely, exacerbate instability.

- Pest and Disease Pressure: Outbreaks of pests or diseases can decimate yields. The prevalence and severity of these threats can vary significantly from year to year, contributing to instability.

Ecosystem Characteristics

The inherent design of an ecosystem plays a critical role in its stability.

- Biodiversity: Perhaps one of the most powerful drivers of stability is biodiversity. Diverse ecosystems, whether natural or agricultural, tend to be more resilient. If one species struggles due to a specific stressor, others may thrive, compensating for the loss and maintaining overall system function.

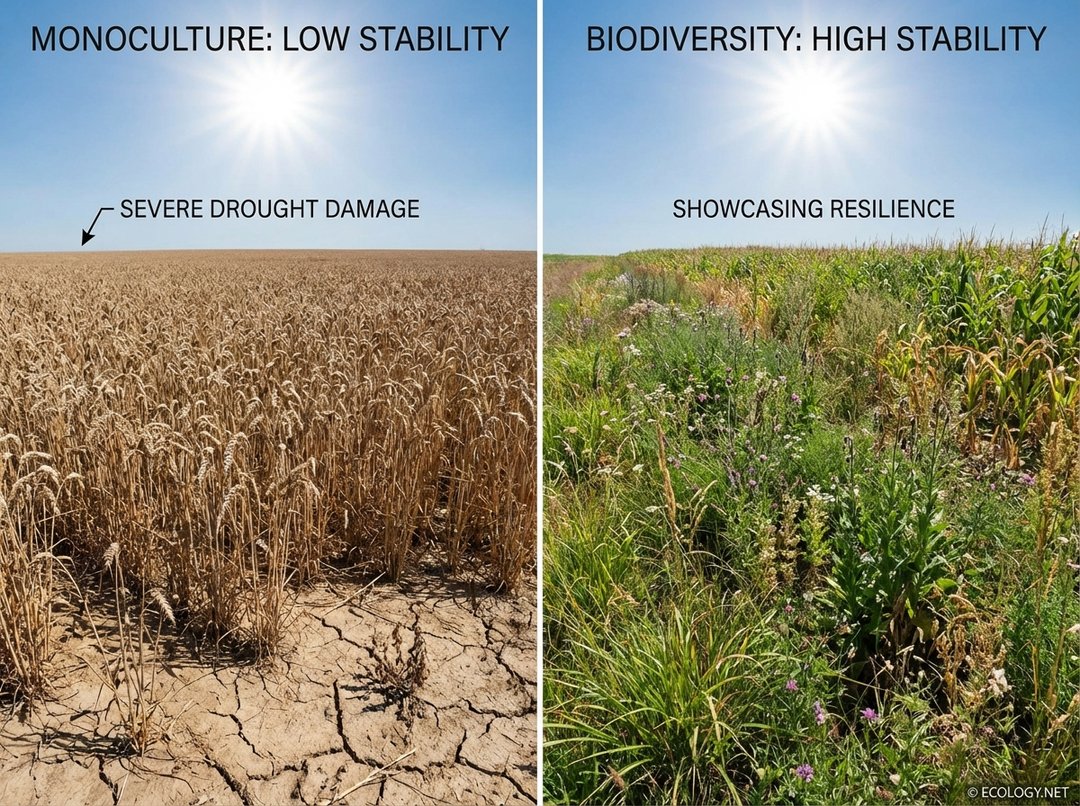

A monoculture, a field planted with a single crop species, is highly vulnerable. A disease or pest that targets that specific crop can wipe out an entire harvest. In contrast, a diverse field with multiple crop species or a natural prairie with many plant types can withstand such an event more effectively. Some species might be affected, but others will remain productive, ensuring a more stable overall yield.

- Functional Diversity: This refers to the variety of roles that different species play within an ecosystem. For example, a diverse array of pollinators or decomposers ensures that these essential functions continue even if some species decline.

- Trophic Complexity: Ecosystems with complex food webs, featuring multiple predators and prey, tend to be more stable. Redundancy in these interactions provides buffers against disturbances.

Management Practices

Human choices in managing land and resources profoundly impact yield stability.

- Crop Rotation: Rotating different crops helps break pest and disease cycles, improves soil health, and balances nutrient uptake, leading to more consistent yields over time.

- Intercropping and Polyculture: Growing multiple crops together in the same field can mimic natural biodiversity, enhancing resilience against pests, diseases, and environmental stressors.

- Sustainable Land Use: Practices like conservation tillage, cover cropping, and agroforestry protect soil from erosion, improve water infiltration, and foster beneficial microbial communities, all contributing to stability.

- Water Management: Efficient irrigation techniques, rainwater harvesting, and drought-resistant crop varieties are crucial in regions facing water scarcity.

Advanced Concepts: Portfolio Effects and Temporal Decorrelation

Beyond simple biodiversity, ecologists and economists have identified more nuanced mechanisms that contribute to stability, often drawing parallels with financial investment strategies.

The Portfolio Effect

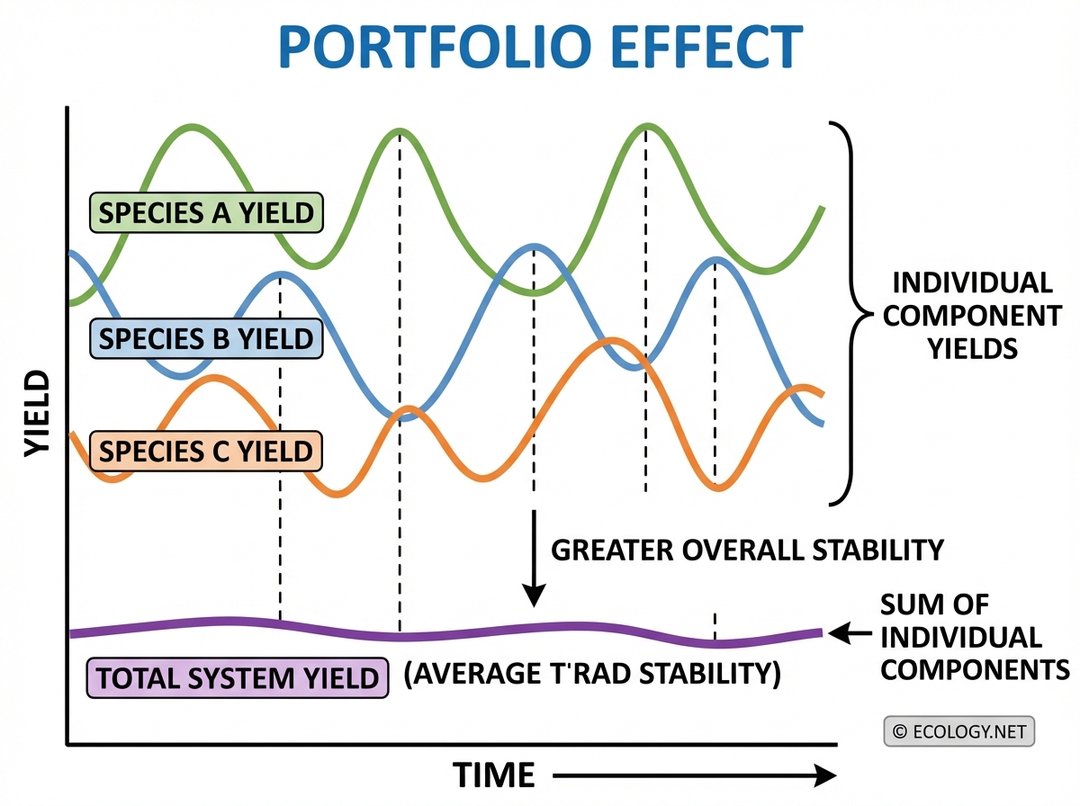

This concept, borrowed from finance, suggests that combining multiple, somewhat independent components can lead to a more stable overall outcome than any single component could achieve alone. In ecology, this means that a diverse community of species, each responding differently to environmental fluctuations, can collectively produce a more stable total yield or ecosystem function.

Imagine three different plant species in a field. Species A might thrive in wet years but struggle in dry years. Species B might prefer dry conditions. Species C might be more tolerant of temperature extremes. When these species are grown together, their individual fluctuations tend to cancel each other out. When Species A’s yield drops, Species B’s might rise, leading to a relatively consistent total yield for the entire field. The overall system becomes more stable because the risks are spread across a “portfolio” of different species.

Temporal Decorrelation

Closely related to the portfolio effect, temporal decorrelation describes how the responses of different species or components to environmental changes are not perfectly synchronized over time. One species might peak in productivity in one year, while another peaks in a different year. This “out-of-phase” fluctuation prevents all components from failing or succeeding simultaneously, thereby buffering the overall system against extreme variability.

For example, different crop varieties might have varying sensitivities to early-season drought versus late-season heat. Planting a mix of these varieties ensures that even if one variety suffers significantly from a particular stressor in a given year, others might be less affected or even benefit, leading to a more stable aggregate harvest.

Measuring Yield Stability

Quantifying yield stability typically involves statistical measures that assess the variability of yield data over time. Common metrics include:

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): This is the standard deviation of yield divided by the mean yield, expressed as a percentage. A lower CV indicates higher stability.

- Standard Deviation: While simpler, the standard deviation alone can be misleading if comparing systems with very different average yields.

- Stability Indices: More complex indices exist that incorporate both mean yield and its variability, providing a comprehensive measure of performance.

Enhancing Yield Stability: Practical Strategies

The understanding of yield stability offers clear pathways for building more resilient and sustainable systems.

In Agricultural Contexts

- Diversification: This is the cornerstone.

- Crop Diversity: Planting multiple crop species, varieties, or even different genetic strains within a single species.

- Livestock Integration: Combining crop and livestock farming can create more resilient systems, with livestock providing manure for soil fertility and an alternative income stream.

- Agroforestry: Integrating trees into farming systems provides multiple benefits, including soil stabilization, microclimate regulation, and additional products, all contributing to stability.

- Soil Conservation: Practices like no-till farming, cover cropping, and adding organic matter are crucial for building healthy, resilient soils that buffer against environmental extremes.

- Integrated Pest Management (IPM): Utilizing a combination of biological, cultural, and chemical controls to manage pests minimizes reliance on single solutions and reduces the risk of widespread crop failure.

- Climate-Resilient Varieties: Developing and deploying crop varieties that are tolerant to drought, heat, or specific diseases can significantly enhance stability in a changing climate.

In Ecological Contexts

- Habitat Restoration and Protection: Preserving and restoring natural habitats enhances biodiversity, which in turn strengthens the stability of ecosystem functions.

- Sustainable Resource Management: Managing forests, fisheries, and water resources in a way that maintains their ecological integrity ensures their long-term stability and productivity.

- Reducing Anthropogenic Stressors: Minimizing pollution, habitat fragmentation, and climate change impacts directly contributes to the stability of natural systems.

Conclusion

Yield stability is more than an academic concept; it is a fundamental principle for navigating an increasingly unpredictable world. Whether in the fields that feed us or the wildlands that sustain our planet, the ability of a system to consistently deliver its bounty is a testament to its health and resilience. By understanding the drivers of stability, from the power of biodiversity to the elegant mechanics of the portfolio effect, humanity can cultivate practices and policies that foster not just high yields, but reliable, enduring ones. Embracing yield stability is an investment in a more secure, sustainable, and harmonious future for all.