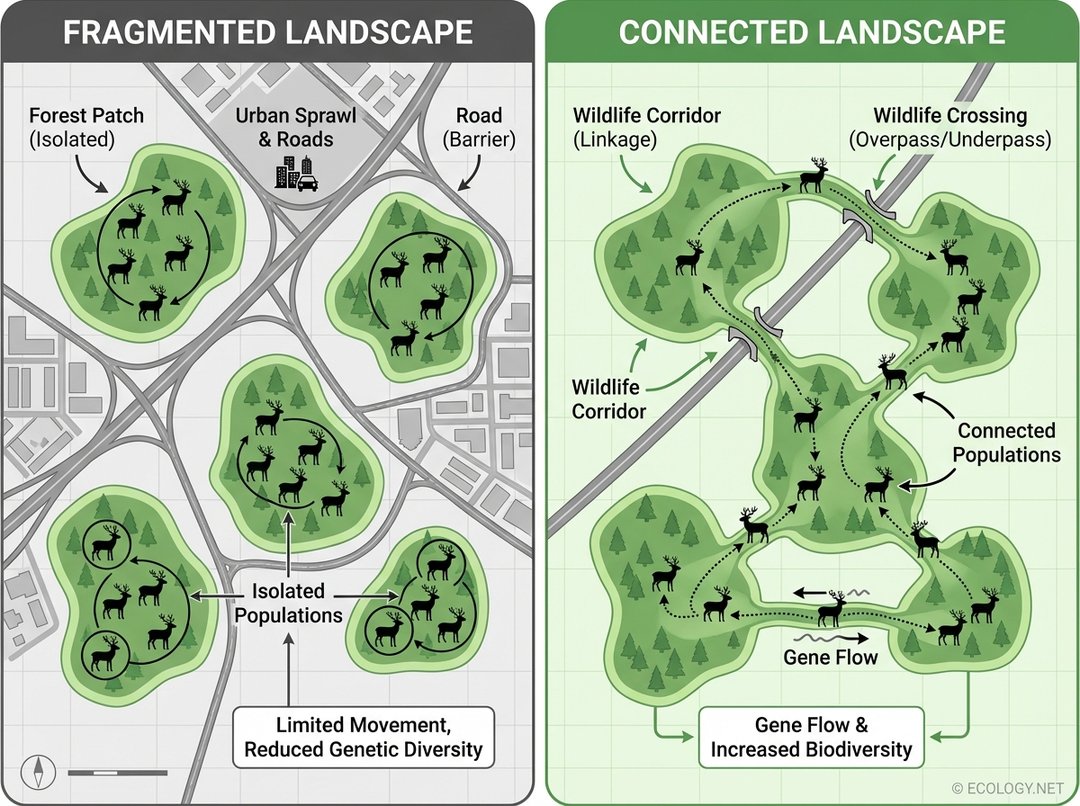

In an increasingly human-dominated world, the natural landscapes that once stretched unbroken for miles are now often fragmented, carved up by roads, cities, and agricultural fields. This fragmentation creates isolated “islands” of habitat, trapping wildlife populations and threatening their long-term survival. Imagine a vibrant ecosystem, bustling with diverse life, suddenly cut into pieces. This is the challenge that wildlife corridors seek to address, offering a lifeline to nature by re-stitching the fabric of our planet.

The Urgent Need for Connectivity

Habitat fragmentation is a silent crisis, severing the vital connections that allow species to thrive. When large natural areas are broken into smaller, isolated patches, animals find themselves confined. This confinement leads to several critical problems:

- Limited Resources: Smaller areas mean fewer food sources, less water, and reduced shelter, especially during seasonal changes.

- Increased Vulnerability: Isolated populations are more susceptible to local extinction from disease, natural disasters, or even random events. A single wildfire or severe storm could wipe out an entire population.

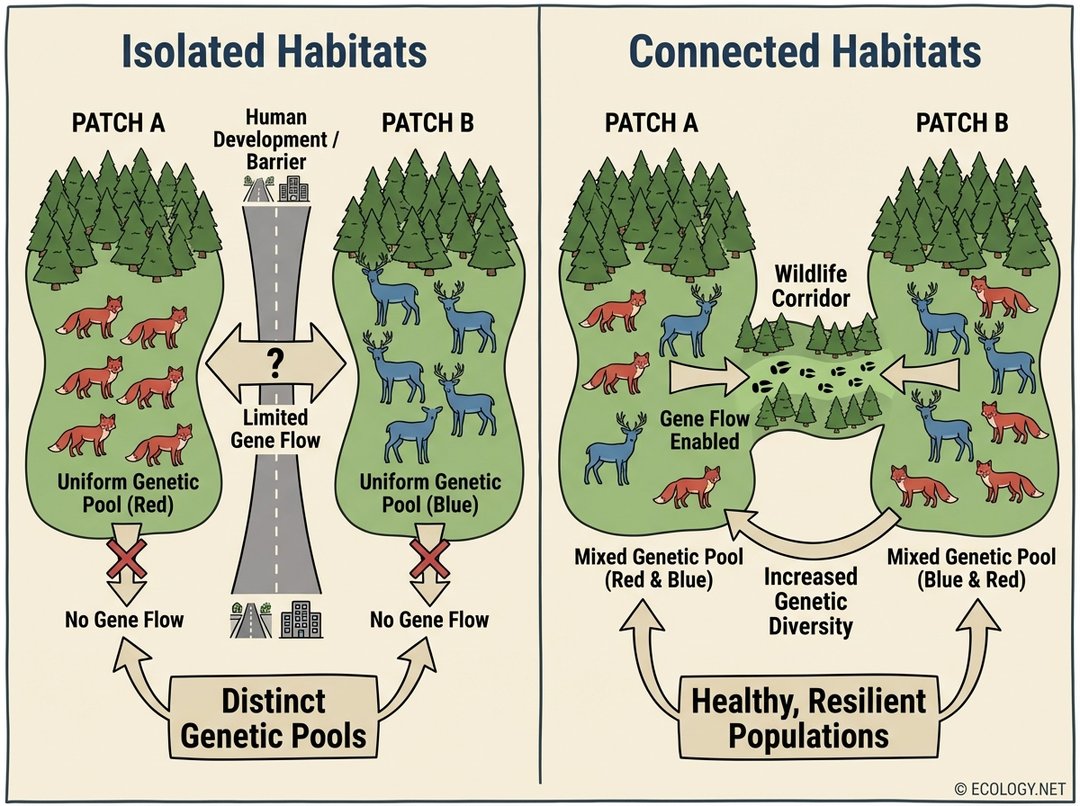

- Genetic Isolation: Perhaps the most insidious threat is the loss of genetic diversity. Without the ability to move and breed with individuals from other populations, species become inbred, weakening their resilience to environmental changes and diseases.

Wildlife corridors emerge as a powerful solution to these challenges. They are essentially pathways of habitat that connect otherwise isolated natural areas, allowing animals to move safely between them. These connections are crucial for maintaining healthy, robust ecosystems.

Why Are Wildlife Corridors Important?

The benefits of wildlife corridors extend far beyond simply allowing animals to cross a road. They are fundamental tools for biodiversity conservation, supporting ecological processes on a grand scale.

Enhancing Genetic Diversity

One of the most critical roles of wildlife corridors is facilitating gene flow. When populations are isolated, they can become genetically distinct and less diverse. This lack of diversity makes them more vulnerable to disease and less adaptable to environmental changes. Corridors allow individuals to move between populations, introducing new genetic material and strengthening the overall health and resilience of the species.

Supporting Population Viability

Connected populations are larger and more stable. If a local population faces a threat, individuals from connected areas can recolonize, preventing local extinctions. This is particularly important for species with large home ranges, such as bears, wolves, or migratory birds, which require vast territories to find food, mates, and suitable breeding grounds.

Adapting to Climate Change

As global climates shift, many species need to move to new areas to find suitable temperatures and resources. Wildlife corridors provide the necessary pathways for these climate-induced migrations, allowing species to adapt to changing conditions rather than being trapped in unsuitable habitats.

Reducing Human-Wildlife Conflict

By providing safe passages, corridors can reduce the incidence of animals wandering into human settlements or onto busy roads, thereby minimizing collisions and other negative interactions that can be dangerous for both wildlife and people.

Diverse Forms of Wildlife Corridors

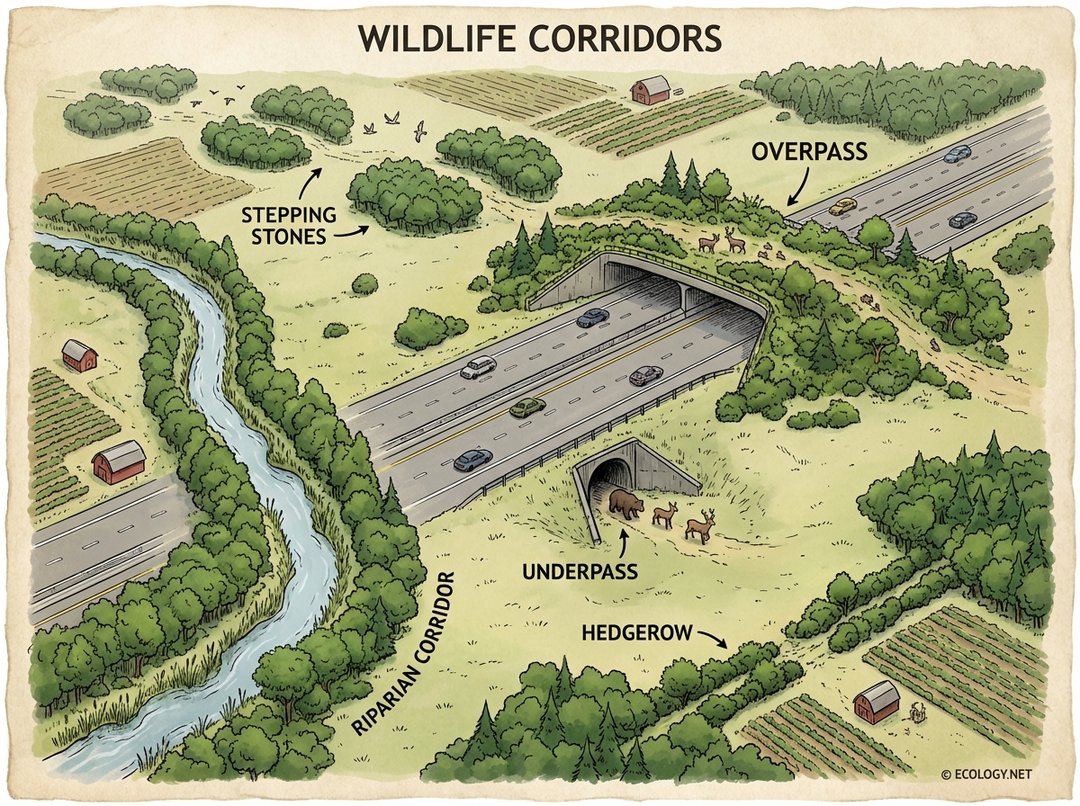

Wildlife corridors are not one-size-fits-all solutions. They come in many forms, each designed to suit the specific landscape, species, and human infrastructure present. Understanding these diverse types is key to effective conservation planning.

Overpasses and Land Bridges

These are structures built over major highways or railways, often covered with natural vegetation to mimic the surrounding landscape. They allow animals like deer, elk, bears, and even smaller mammals to cross safely above traffic. A famous example is the wildlife overpasses in Banff National Park, Canada, which have significantly reduced wildlife vehicle collisions.

Underpasses and Tunnels

Conversely, underpasses are tunnels or culverts built beneath roads or railways. They are particularly effective for species that prefer to move through sheltered environments, such as amphibians, reptiles, small mammals, and even larger animals like cougars or bears. Some underpasses are specifically designed for aquatic species, allowing them to navigate beneath roads that cross streams.

Riparian Corridors

These are strips of vegetation that follow the banks of rivers, streams, and other waterways. Riparian zones are naturally rich in biodiversity and provide essential habitat and movement routes for a vast array of species, from insects and fish to birds and large mammals. They are crucial for connecting upland habitats and protecting water quality.

Hedgerows

Common in agricultural landscapes, hedgerows are narrow strips of dense bushes and trees that often form boundaries between fields. While seemingly simple, they provide vital connectivity for smaller animals, birds, and insects, allowing them to move between larger forest patches or find shelter and food in otherwise open environments.

Stepping Stones

Sometimes, a continuous corridor is not feasible. In such cases, “stepping stones” are used. These are small, isolated patches of suitable habitat strategically placed to act as temporary resting or feeding points for animals as they move across a fragmented landscape. Birds, bats, and even some insects can utilize these patches to traverse otherwise inhospitable areas.

Challenges and Considerations in Corridor Implementation

While the concept of wildlife corridors is elegant and effective, their implementation comes with a unique set of challenges:

- Cost and Land Acquisition: Building large structures like overpasses or acquiring land for natural corridors can be incredibly expensive and complex, often requiring collaboration between government agencies, landowners, and conservation organizations.

- Effectiveness Monitoring: It is crucial to monitor whether corridors are actually being used by target species and if they are achieving their conservation goals. This involves wildlife tracking, camera traps, and genetic studies.

- “Ecological Traps”: A poorly designed corridor can inadvertently lead animals into danger, such as funneling them towards busy roads or areas with high human activity. Careful planning and placement are essential to avoid creating these “ecological traps.”

- Disease Transmission: While generally beneficial for genetic diversity, increased movement of animals can also facilitate the spread of diseases between populations. This risk must be managed through careful monitoring and, where necessary, mitigation strategies.

- Human-Wildlife Coexistence: As corridors increase animal movement, there can be a need for greater public education and management strategies to ensure safe coexistence between humans and wildlife, especially for larger or potentially dangerous species.

Success Stories and the Future of Connectivity

Despite the challenges, numerous successful wildlife corridor projects around the globe demonstrate their immense value. From the extensive network of green bridges and tunnels across Europe to specific crossings for endangered species in North America and Australia, these initiatives are proving that humans and wildlife can coexist and thrive.

The future of wildlife corridors lies in integrated landscape planning. This involves considering connectivity needs at every stage of development, from urban planning to agricultural practices and infrastructure projects. It requires collaboration among scientists, engineers, policymakers, and local communities to design and implement effective solutions that benefit both nature and society.

Public awareness and support are also vital. Understanding the critical role these pathways play in maintaining healthy ecosystems encourages greater investment and protection for these essential natural connections.

Conclusion

Wildlife corridors are more than just bridges or tunnels; they are arteries of life, vital for the health and resilience of our planet’s biodiversity. In a world increasingly shaped by human activity, these ecological lifelines offer a powerful and hopeful strategy for conservation. By reconnecting fragmented habitats, we empower species to adapt, thrive, and maintain the intricate balance of nature, ensuring a richer, more vibrant world for generations to come.