Imagine a world where animals are trapped in isolated islands of nature, unable to reach food, mates, or new territories. This is the stark reality many species face due to human development, a phenomenon known as habitat fragmentation. Roads, cities, and agricultural lands carve up once-continuous landscapes, turning vast natural areas into disconnected patches. But there is a powerful solution emerging from the field of conservation biology: the wildlife corridor.

Wildlife corridors are essentially lifelines for nature, designed to reconnect these fragmented habitats. They are pathways that allow animals to move safely between different areas, ensuring their survival and the health of entire ecosystems. From majestic elk crossing specially built overpasses to tiny insects navigating a series of stepping stone habitats, these corridors are vital for maintaining biodiversity in an increasingly human-dominated world.

The Silent Crisis: Habitat Fragmentation

For millennia, animals roamed freely across vast landscapes, following ancient migration routes, seeking new resources, and finding mates. This natural movement is fundamental to ecological balance. However, the rapid expansion of human infrastructure has drastically altered this reality. Highways slice through forests, urban sprawl encroaches on wetlands, and agricultural fields replace natural grasslands. The result is habitat fragmentation, a process that breaks large, continuous habitats into smaller, isolated fragments.

This isolation has severe consequences for wildlife. Populations trapped in small patches become vulnerable to local extinction due to a lack of genetic diversity, limited food resources, and increased susceptibility to disease. They cannot adapt to environmental changes, find new mates, or escape threats. The very fabric of their existence is torn apart.

The image above powerfully illustrates this challenge. On one side, isolated habitat patches leave animals stranded. On the other, a wildlife corridor provides a crucial link, allowing species to move freely and maintain healthy populations. This visual contrast highlights the urgent need for connectivity in conservation efforts.

Types of Wildlife Corridors: Ingenious Solutions

Wildlife corridors come in many forms, each tailored to the specific landscape, species, and challenges at hand. Their design often reflects a blend of ecological science and engineering ingenuity.

Overpasses and Underpasses: Bridging the Divide

Perhaps the most iconic examples of wildlife corridors are the large structures built to help animals cross major human barriers, particularly roads. These include:

- Wildlife Overpasses: These are bridges covered with natural vegetation, designed to mimic the surrounding landscape. They allow animals to safely cross over busy highways, preventing collisions and reconnecting habitats.

- Wildlife Underpasses: Tunnels, culverts, and other subterranean passages provide safe routes for animals to travel beneath roads or railways. These can range from small culverts for amphibians and small mammals to large, spacious tunnels for bears and deer.

The image above showcases a magnificent wildlife overpass, reminiscent of those found in places like Banff National Park. Covered in lush trees and shrubs, it creates a seamless extension of the forest, allowing large mammals like the elk pictured to cross a multi-lane highway without danger. Such structures are monumental achievements in conservation engineering.

Natural and Semi-Natural Corridors

Not all corridors require extensive construction. Many leverage existing natural features or enhance them:

- Riparian Corridors: These are strips of vegetation along rivers, streams, and wetlands. Waterways naturally attract a wide array of wildlife and the vegetated banks provide excellent cover and pathways for movement.

- Hedgerows and Treelines: In agricultural landscapes, lines of trees and shrubs between fields can act as mini-corridors, offering shelter and routes for birds, insects, and small mammals.

- Forest Patches and Greenbelts: Urban planning can incorporate green spaces, parks, and connected forest patches to create corridors within developed areas, benefiting both wildlife and human well-being.

Stepping Stones: Islands of Connectivity

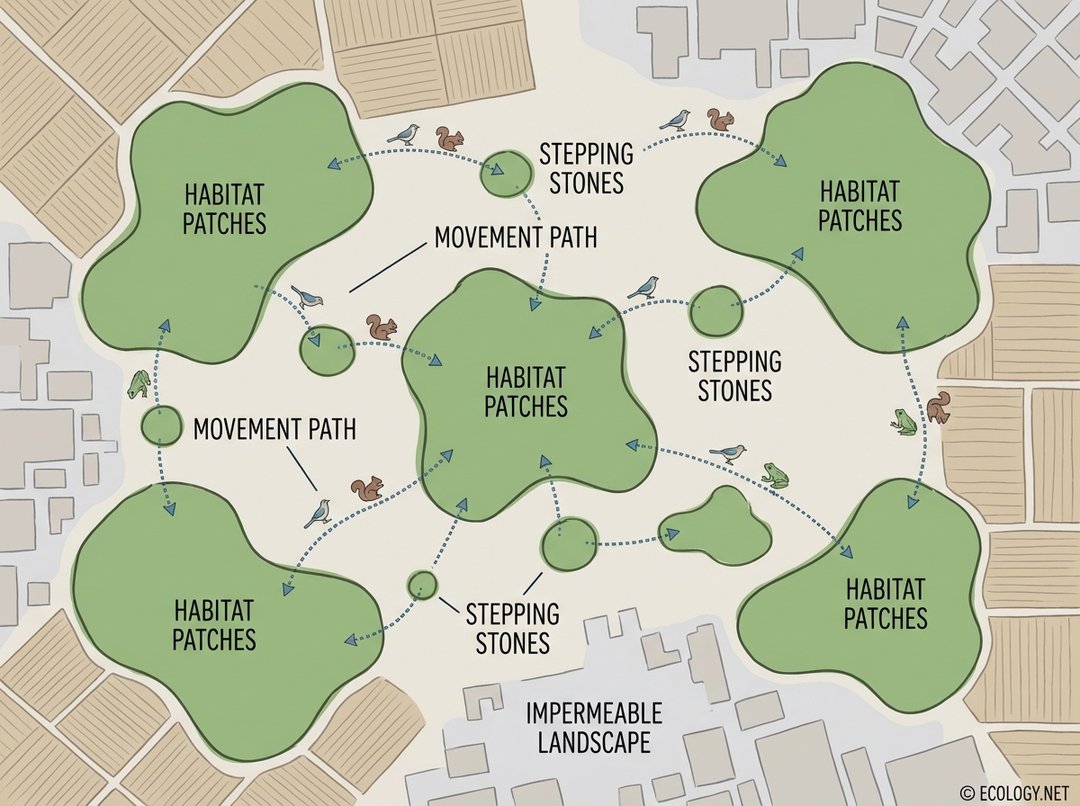

Sometimes, a continuous corridor is not feasible. In such cases, a series of smaller, strategically placed habitat patches can serve as “stepping stones.” These isolated but closely spaced patches allow animals to move incrementally across an otherwise inhospitable landscape, resting and foraging along the way.

The diagram above clearly illustrates the stepping stone concept. Smaller green patches are dotted between larger habitat areas, providing crucial resting and foraging points for animals to traverse an open, less hospitable landscape. This approach is particularly effective for species that can fly or make short movements across open ground, such as birds and some insects.

The Indispensable Benefits of Connectivity

The implementation of wildlife corridors brings a multitude of ecological benefits, underscoring their critical role in modern conservation.

- Enhanced Genetic Diversity: By allowing individuals from different populations to interbreed, corridors prevent inbreeding and bolster the genetic health of species, making them more resilient to disease and environmental change.

- Facilitated Migration and Dispersal: Corridors enable animals to follow seasonal migration routes, find new territories as they mature, and seek out new food sources, all essential behaviors for survival.

- Reduced Human-Wildlife Conflict: By guiding animals away from dangerous human infrastructure, especially roads, corridors significantly reduce wildlife mortality from vehicle collisions, benefiting both animals and human safety.

- Climate Change Adaptation: As climates shift, species need to move to more suitable habitats. Corridors provide the pathways necessary for these crucial range shifts, offering a vital tool for climate change adaptation.

- Ecosystem Health: The movement of animals facilitates seed dispersal, pollination, and nutrient cycling, all of which are fundamental processes for maintaining healthy and functioning ecosystems.

Designing Effective Wildlife Corridors: A Scientific Endeavor

Creating a successful wildlife corridor is far more complex than simply drawing a green line on a map. It requires a deep understanding of ecology, animal behavior, and landscape dynamics. Scientists and conservationists consider several key factors:

- Target Species: The design must cater to the specific needs of the animals intended to use the corridor. A corridor for deer will differ greatly from one for salamanders or migratory birds.

- Width and Length: Corridors need to be wide enough to provide adequate cover and a sense of security for animals, minimizing their exposure to threats. Their length must be sufficient to connect distant habitats effectively.

- Vegetation and Habitat Quality: The corridor itself must offer suitable habitat, including appropriate food, water, and shelter. Native vegetation is crucial for attracting and sustaining wildlife.

- Location and Connectivity: Corridors must be strategically placed to link core habitats where animals reside. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and animal tracking data are invaluable tools for identifying optimal routes.

- Minimizing Disturbances: Noise, light pollution, and human activity within or adjacent to corridors can deter wildlife. Designs aim to minimize these disturbances.

- Land Ownership and Management: Establishing corridors often involves complex negotiations with landowners, government agencies, and local communities. Long-term management plans are essential for their continued effectiveness.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite their immense benefits, establishing wildlife corridors presents significant challenges. The financial cost of land acquisition, construction, and ongoing maintenance can be substantial. Public perception and resistance from landowners can also be hurdles. Furthermore, monitoring the effectiveness of corridors requires long-term commitment and scientific rigor.

However, the growing recognition of their importance is driving innovative solutions. Collaborative efforts between governments, non-governmental organizations, private landowners, and local communities are proving successful. Funding mechanisms, including grants, conservation easements, and public-private partnerships, are helping to overcome financial barriers. Education and outreach programs are vital for building public support and fostering a sense of shared responsibility for wildlife conservation.

Global initiatives like the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative, which aims to connect habitats across a vast transboundary region, demonstrate the power of large-scale corridor planning. Similarly, the European Green Belt, following the former Iron Curtain, is transforming a historical barrier into an ecological lifeline. These ambitious projects serve as inspiring examples of what can be achieved when conservation is prioritized.

The Future of Connectivity Conservation

As human populations continue to grow and landscapes become increasingly fragmented, the role of wildlife corridors will only become more critical. Integrating connectivity into urban planning, promoting sustainable land use practices, and leveraging new technologies for monitoring and research will be key to their success. Citizen science initiatives, where local communities contribute to data collection and habitat restoration, also play an increasingly important role.

Wildlife corridors are more than just pathways for animals; they are symbols of hope and a testament to our commitment to coexisting with nature. By reconnecting fragmented landscapes, we are not only safeguarding individual species but also ensuring the health and resilience of the entire planet. These vital lifelines are a powerful investment in a future where both humans and wildlife can thrive.