Wetlands: Earth’s Vital Watery Worlds

Often misunderstood or overlooked, wetlands are among the planet’s most dynamic and productive ecosystems. These unique environments, where land and water intimately intertwine, play an indispensable role in maintaining ecological balance and supporting countless forms of life, including our own. Far from being mere soggy patches of ground, wetlands are complex natural systems that offer a wealth of benefits, from purifying our water to protecting our coastlines.

What Exactly *Are* Wetlands? The Three Pillars of Definition

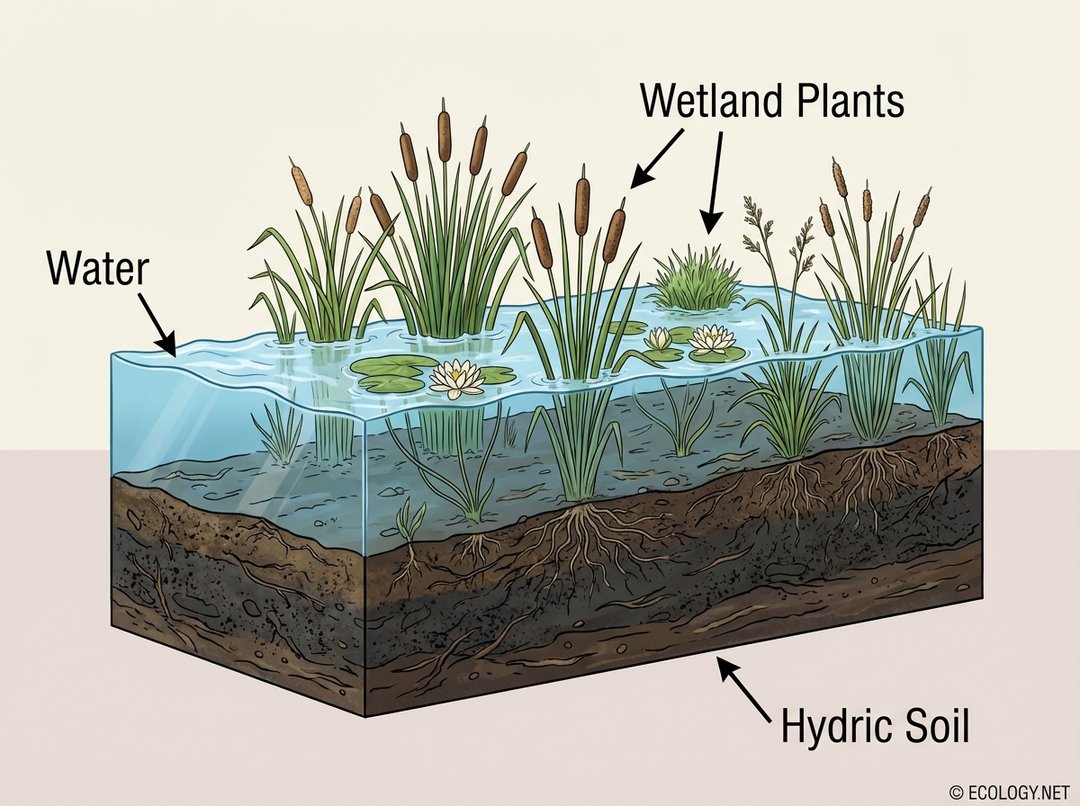

To truly understand wetlands, it is essential to grasp their fundamental characteristics. Ecologists define wetlands by the presence of three key elements, often referred to as the “three pillars”:

- Hydrology (Water): The most obvious characteristic is the presence of water, either at the surface or within the root zone of the soil, for a significant period during the growing season. This water can come from various sources, including rainfall, groundwater, tides, or overflowing rivers.

- Hydric Soil: Due to the prolonged presence of water, wetland soils develop unique properties. These “hydric soils” are saturated, often anaerobic (lacking oxygen), and typically dark in color, indicating the accumulation of organic matter that decomposes slowly in waterlogged conditions.

- Hydrophytes (Wetland Plants): Plants growing in wetlands are specially adapted to thrive in saturated soil conditions. These “hydrophytes” possess unique physiological and anatomical features that allow them to survive and even flourish where most other plants would perish from lack of oxygen in their roots.

These three components work in concert, creating the distinct environments we recognize as wetlands. Without all three, an area is not classified as a wetland.

Earth’s Unsung Heroes: The Incredible Functions of Wetlands

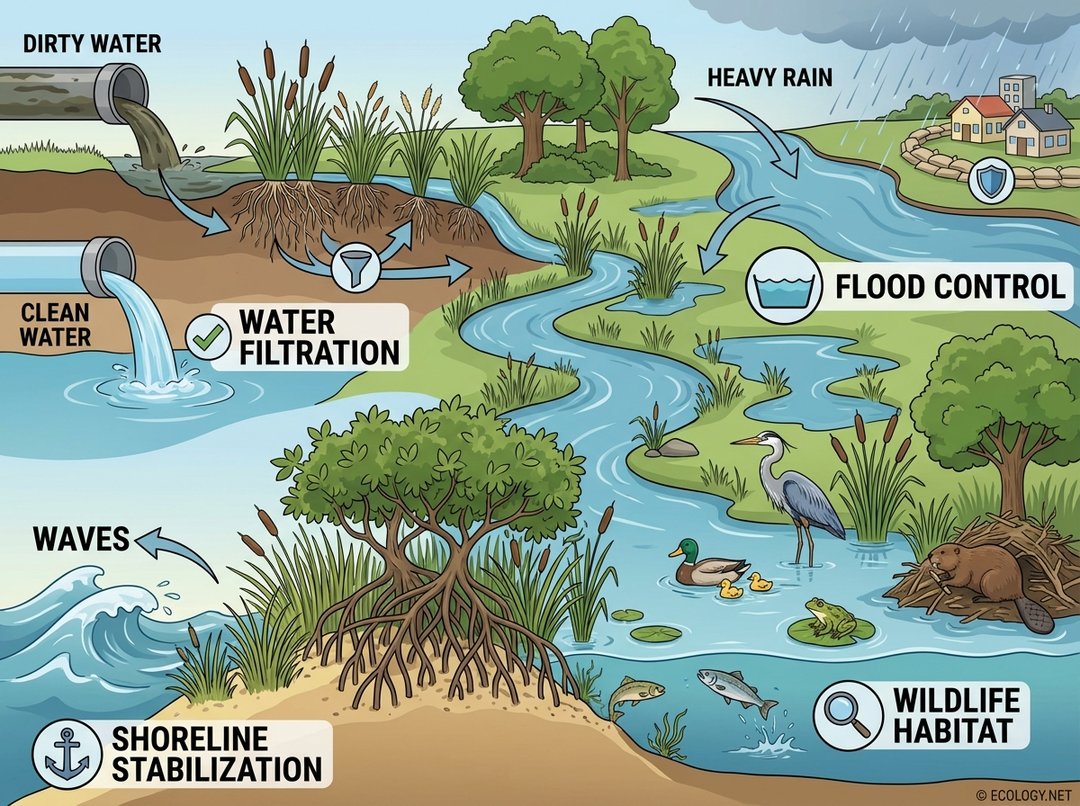

The ecological services provided by wetlands are vast and profoundly impact both natural systems and human societies. These watery landscapes act as nature’s multi-functional utility providers, performing tasks that would be incredibly expensive or impossible to replicate artificially.

- Water Filtration and Purification: Wetlands are often called “nature’s kidneys.” As water flows through them, wetland plants and soils act as natural filters, trapping sediments, absorbing pollutants like excess nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), and breaking down harmful chemicals. This process significantly improves water quality downstream, benefiting drinking water supplies and aquatic life.

- Flood Control and Storm Protection: During heavy rainfall or storm surges, wetlands act like giant sponges, absorbing and storing excess water. This reduces the severity of floods in surrounding areas, protecting communities and infrastructure. Coastal wetlands, such as mangrove swamps and salt marshes, also buffer shorelines against erosion from waves and storm surges, acting as natural protective barriers.

- Wildlife Habitat and Biodiversity Hotspots: Wetlands are incredibly biodiverse, providing critical habitats for a vast array of species. They serve as breeding grounds, nurseries, and feeding areas for migratory birds, fish, amphibians, reptiles, and numerous invertebrates. Many endangered species rely exclusively on wetland environments for their survival.

- Groundwater Recharge: In many regions, wetlands play a crucial role in replenishing groundwater supplies. As water slowly seeps through wetland soils, it can percolate down to underground aquifers, which are vital sources of drinking water for many communities.

- Carbon Sequestration: Wetlands, particularly bogs and peatlands, are highly effective at storing carbon. The waterlogged conditions slow down decomposition, allowing vast amounts of organic matter to accumulate as peat, effectively locking away carbon and helping to mitigate climate change.

A World of Wetness: Exploring Diverse Wetland Types

The term “wetland” encompasses a wide variety of environments, each with its own unique characteristics, plant communities, and ecological roles. While all share the three defining pillars, their specific hydrology, soil types, and dominant vegetation lead to remarkable diversity.

Let us explore some of the most common types:

Marshes

Marshes are characterized by herbaceous (non-woody) vegetation, such as grasses, reeds, and sedges, growing in shallow water. They can be freshwater or saltwater. Freshwater marshes, like parts of the Florida Everglades, are teeming with life, while saltwater marshes are common along coastlines, often flooded by tides. They are incredibly productive ecosystems, supporting a rich diversity of birds, fish, and invertebrates.

Swamps

Swamps are wetlands dominated by woody plants, primarily trees and shrubs, that are adapted to saturated soil conditions. These can be freshwater or saltwater. Famous examples include the cypress swamps of the American South, where bald cypress trees stand with their distinctive “knees” protruding from the water, or tupelo swamps. Swamps provide important timber resources and critical habitat for larger wildlife.

Mangrove Swamps

A specialized type of saltwater swamp, mangrove swamps are found in tropical and subtropical coastal regions. They are defined by mangrove trees, which have unique adaptations like prop roots and pneumatophores (aerial roots) that allow them to thrive in salty, oxygen-poor intertidal zones. Mangroves are vital for shoreline stabilization, protecting coasts from erosion and storm surges, and serving as nurseries for many marine species.

Bogs

Bogs are freshwater wetlands characterized by their acidic water, low nutrient levels, and the accumulation of peat, which is partially decayed plant matter, primarily sphagnum moss. Bogs are typically fed by rainwater, making them nutrient-poor. They are often found in cooler climates and host unique, specialized plant life, including carnivorous plants like pitcher plants and sundews, which have evolved to capture insects to supplement their nutrient intake.

Fens

While not always as widely recognized as bogs, fens are another type of peat-accumulating wetland. Unlike bogs, fens are fed by groundwater or surface water that has passed through mineral soil, making them less acidic and more nutrient-rich. They support a greater diversity of plant species than bogs, including sedges, grasses, and wildflowers.

The Future of Wetlands: Challenges and Conservation

Despite their immense value, wetlands are among the most threatened ecosystems globally. Historically, they were often viewed as unproductive lands, drained and filled for agriculture, development, or mosquito control. Today, the threats continue, exacerbated by climate change.

- Habitat Loss and Degradation: Urbanization, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development continue to destroy and fragment wetland habitats.

- Pollution: Runoff from agriculture, industrial discharges, and urban areas introduces pollutants, excess nutrients, and toxins into wetlands, degrading water quality and harming wildlife.

- Altered Hydrology: Dams, diversions, and groundwater extraction can significantly alter the natural water flow to wetlands, disrupting their delicate balance.

- Climate Change: Rising sea levels threaten coastal wetlands, while changes in precipitation patterns and increased frequency of extreme weather events can impact all wetland types.

Recognizing their critical importance, significant efforts are underway worldwide to protect, restore, and sustainably manage wetlands. International treaties, national legislation, and local conservation initiatives aim to reverse past losses and ensure these vital ecosystems continue to provide their invaluable services for future generations. Protecting wetlands is not merely an environmental issue; it is an investment in our planet’s health, our economic well-being, and the biodiversity that enriches all life. Understanding and appreciating these watery worlds is the first step toward their enduring preservation.