Every living organism on Earth plays a role in a grand, interconnected drama of energy and sustenance. From the smallest bacterium to the largest whale, each creature occupies a specific position in the flow of life, a concept ecologists refer to as trophic levels. Understanding these levels is fundamental to grasping how ecosystems function, how energy moves through nature, and ultimately, how all life is sustained.

Imagine the natural world not as a chaotic jumble of organisms, but as a meticulously organized system where energy is captured, transferred, and recycled. This intricate dance of life is governed by who eats whom, forming the very foundation of ecological balance.

The Ecological Hierarchy: Unpacking Trophic Levels

At its core, a trophic level describes an organism’s position in a food chain. The word “trophic” itself comes from the Greek word “trophe,” meaning “nourishment.” These levels illustrate how energy, originally from the sun, flows through an ecosystem, moving from one group of organisms to the next.

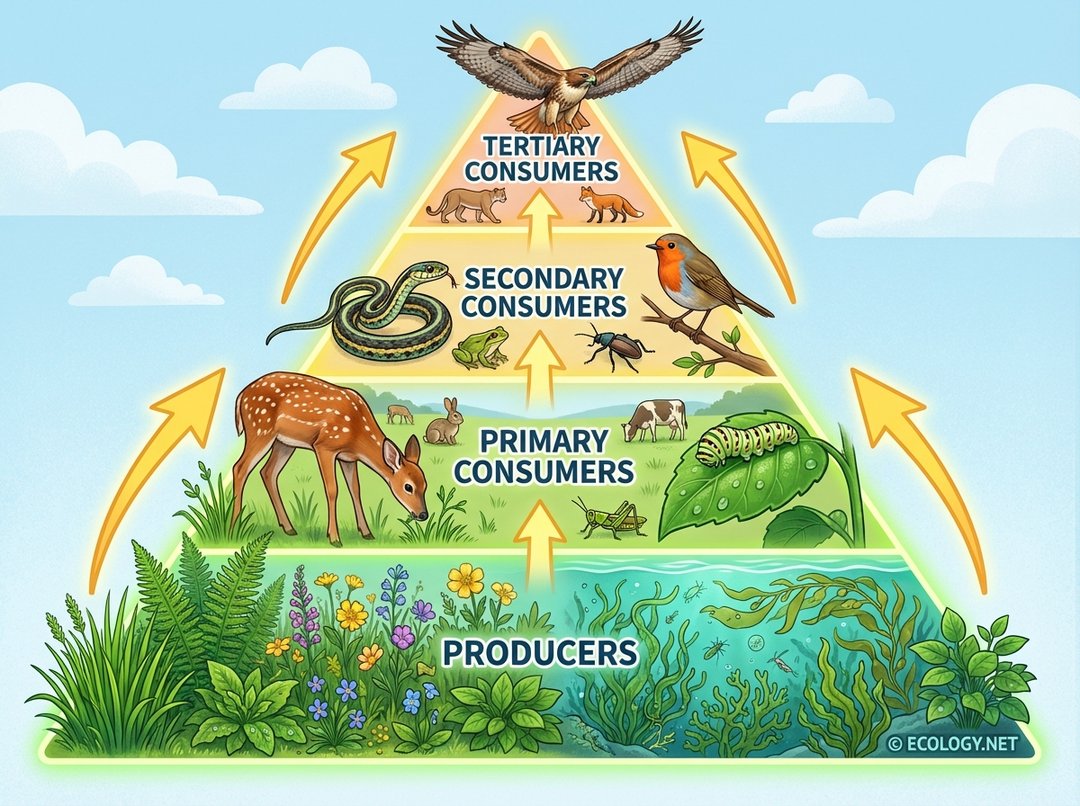

Think of it as a pyramid, with the broadest base representing the organisms that produce their own food, and progressively narrower layers above them representing consumers that feed on the levels below.

Producers: The Foundation of Life

At the very bottom of the trophic pyramid are the producers, also known as autotrophs. These remarkable organisms are the powerhouse of nearly every ecosystem. They convert inorganic energy, primarily sunlight, into organic compounds, essentially creating food from scratch. The most common producers are:

- Plants: Through photosynthesis, plants convert sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into glucose, their energy source. Think of towering trees, lush grasses, and vibrant wildflowers.

- Algae: These aquatic organisms, ranging from microscopic phytoplankton to large seaweeds, are the primary producers in most aquatic environments, forming the base of marine and freshwater food webs.

- Chemoautotrophs: A lesser-known but equally vital group, these organisms, often bacteria, produce food using chemical reactions instead of sunlight. They thrive in extreme environments like deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

Without producers, there would be no energy to fuel the rest of the ecosystem. They are the ultimate source of all organic matter.

Primary Consumers: The Herbivores

Moving up the pyramid, we encounter the primary consumers, or herbivores. These organisms obtain their energy by feeding directly on producers. They are the plant-eaters of the world, transforming plant energy into animal energy.

- Terrestrial Examples:

- Deer grazing on grass and leaves.

- Rabbits munching on clover.

- Caterpillars devouring plant foliage.

- Elephants browsing on shrubs and trees.

- Aquatic Examples:

- Zooplankton feeding on phytoplankton.

- Manatees grazing on seagrass.

- Snails scraping algae from rocks.

Primary consumers form a crucial link, transferring the energy stored in plants to the next trophic level.

Secondary Consumers: The First Carnivores

The next rung on the ladder is occupied by secondary consumers. These are typically carnivores or omnivores that feed on primary consumers. They are the predators of the herbivores.

- Carnivores:

- A fox hunting a rabbit.

- A snake preying on a mouse.

- A spider catching a fly.

- A small fish eating zooplankton.

- Omnivores:

- Bears eating berries and fish.

- Humans consuming both plants and animals.

- Raccoons foraging for various food sources.

Secondary consumers play a vital role in controlling herbivore populations, preventing them from overgrazing and depleting producer resources.

Tertiary Consumers: Apex Predators and Beyond

At the top of many food chains are the tertiary consumers. These are carnivores that feed on secondary consumers. In some ecosystems, there might even be quaternary consumers, feeding on tertiary ones, though this is less common due to energy limitations.

- Examples:

- A hawk preying on a snake that ate a mouse.

- A wolf hunting a fox.

- A large shark eating smaller fish that consumed even smaller fish.

- An owl catching a bird that ate insects.

These top predators, often called apex predators, typically have few or no natural predators themselves. They are critical for maintaining the health and balance of an ecosystem by regulating populations at lower trophic levels.

The Flow of Energy: Why Pyramids are Pyramids

One of the most fundamental principles governing trophic levels is the concept of energy transfer. Energy flows upwards through the pyramid, but not all of it makes the journey. This is often explained by the 10% rule, which states that only about 10% of the energy from one trophic level is transferred to the next. The remaining 90% is lost as heat during metabolic processes, used for life functions like movement and reproduction, or remains unconsumed.

This significant energy loss explains why trophic pyramids are always wider at the base and narrow towards the top. There simply isn’t enough energy to support an infinitely long food chain or a massive population of apex predators. This energy constraint limits the number of trophic levels an ecosystem can sustain, typically to four or five.

Food Chains vs. Food Webs: The Real Picture

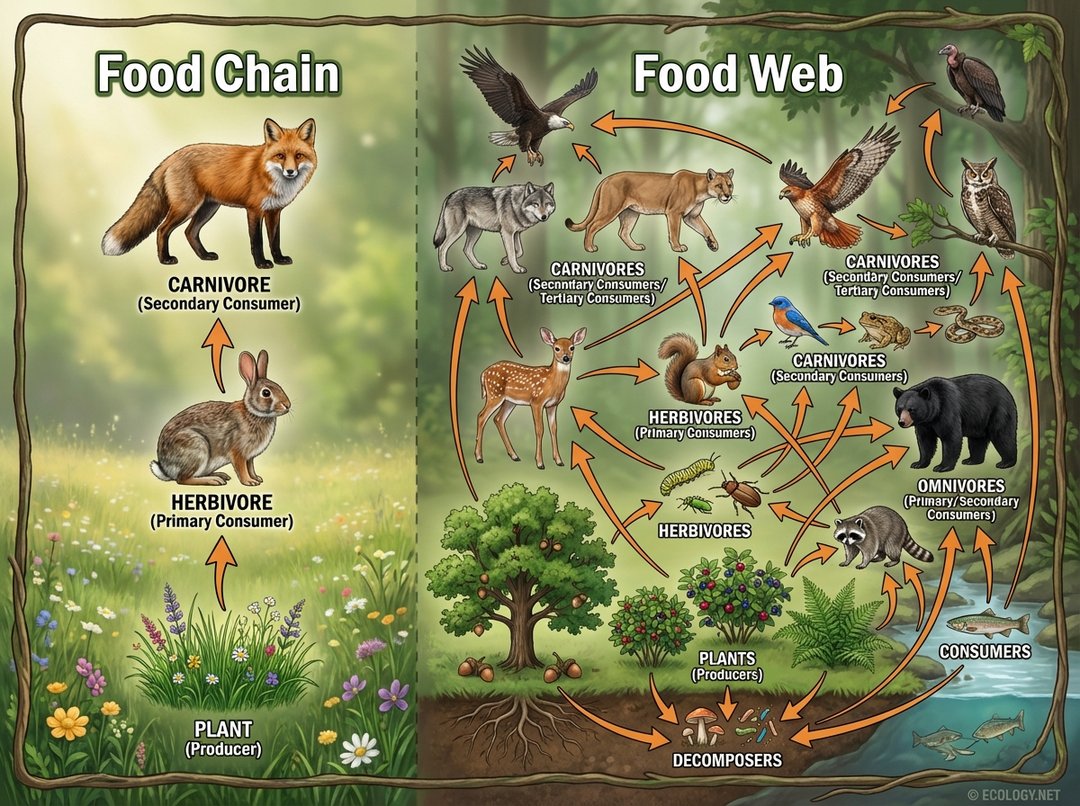

While the concept of a simple food chain is useful for illustrating direct energy transfer, real ecosystems are far more complex. Organisms rarely eat just one type of food, and they are often preyed upon by multiple different species.

The Simplicity of a Food Chain

A food chain depicts a single, linear pathway of energy flow. For example:

Grass → Rabbit → Fox

This shows a clear, direct relationship, but it is an oversimplification of nature.

The Complexity of a Food Web

A food web, on the other hand, illustrates the intricate network of feeding relationships within an ecosystem. It shows that:

- Many producers are eaten by multiple primary consumers.

- Primary consumers can be prey for several secondary consumers.

- Omnivores can occupy multiple trophic levels simultaneously.

- A single species might be part of several different food chains within the same web.

Food webs provide a much more accurate and holistic view of energy flow and ecological interconnectedness. They highlight the resilience of ecosystems; if one food source becomes scarce, an organism might have alternative options. However, they also reveal vulnerabilities; the removal of a key species can have cascading effects throughout the entire web.

Decomposers: Nature’s Essential Recyclers

While producers and consumers are busy capturing and transferring energy, another crucial group of organisms works tirelessly behind the scenes: the decomposers. Often overlooked in discussions of trophic levels, decomposers are absolutely vital for the health and sustainability of every ecosystem.

Decomposers are organisms that break down dead organic matter, including dead plants, animals, and waste products. They are the ultimate recyclers, returning essential nutrients back into the soil and water, making them available for producers to use once again. Without decomposers, nutrients would remain locked up in dead organisms, and life as we know it would grind to a halt.

Key Decomposers Include:

- Bacteria: Microscopic powerhouses that break down organic compounds at a molecular level. They are ubiquitous in soil, water, and even within other organisms.

- Fungi: Mushrooms, molds, and yeasts are masters of decomposition. They release enzymes that break down complex organic materials, such as cellulose and lignin in wood, which other organisms cannot digest.

- Detritivores: These are organisms that physically consume dead organic matter. Examples include earthworms, millipedes, dung beetles, and some types of snails. They fragment the material, increasing the surface area for bacteria and fungi to act upon.

The work of decomposers completes the nutrient cycle, ensuring that the building blocks of life are continuously reused, allowing ecosystems to thrive indefinitely.

Ecological Implications and Human Impact

Understanding trophic levels is not just an academic exercise; it has profound implications for environmental science, conservation, and even human health.

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification

The energy transfer inefficiencies across trophic levels also have a darker side when it comes to pollutants. Certain toxins, such as heavy metals (mercury, lead) and persistent organic pollutants (DDT, PCBs), do not break down easily. When these substances enter an ecosystem, they can accumulate in the tissues of organisms, a process called bioaccumulation.

As these contaminated organisms are consumed by predators, the concentration of the toxin increases at each successive trophic level. This phenomenon is known as biomagnification. For example, a small amount of mercury in algae can become highly concentrated in the fish that eat the algae, and even more so in the birds or humans that eat those fish. This is why apex predators, including humans, are often at the highest risk from environmental contaminants.

Human Influence on Trophic Structures

Human activities can significantly alter trophic levels and food webs:

- Overfishing: Removing large numbers of fish from specific trophic levels can disrupt marine food webs, leading to population explosions of some species and declines in others.

- Habitat Destruction: Loss of habitat can eliminate producers or critical prey species, causing ripple effects throughout the entire food web.

- Pollution: As seen with biomagnification, pollutants can weaken or eliminate species at higher trophic levels, impacting ecosystem stability.

- Introduction of Invasive Species: Non-native species can outcompete native producers or consumers, or become new predators, drastically altering existing trophic relationships.

- Climate Change: Shifts in temperature and weather patterns can affect the distribution and abundance of species at all trophic levels, from plant growth to predator migration patterns.

Recognizing these impacts is the first step towards developing sustainable practices and conservation strategies that protect the delicate balance of our planet’s ecosystems.

Conclusion: The Interconnected Web of Life

Trophic levels provide a powerful framework for understanding the fundamental organization and dynamics of life on Earth. From the sun-powered producers to the top-tier consumers and the indispensable decomposers, every organism plays a critical role in the continuous flow of energy and nutrients that sustains our world. The intricate dance of food chains and food webs highlights the profound interconnectedness of all living things, reminding us that the health of one part of an ecosystem is inextricably linked to the health of the whole.

By appreciating the elegance and complexity of trophic levels, we gain a deeper respect for the natural world and the vital importance of preserving its delicate balance for future generations.