Imagine a delicate web, intricately woven, where every strand is connected to another. Now, imagine plucking one strand. What happens? Does the entire web unravel, or does the disturbance simply fade away? In the natural world, this interconnectedness is not just a metaphor, it is a fundamental reality, and few concepts illustrate it as powerfully as the trophic cascade.

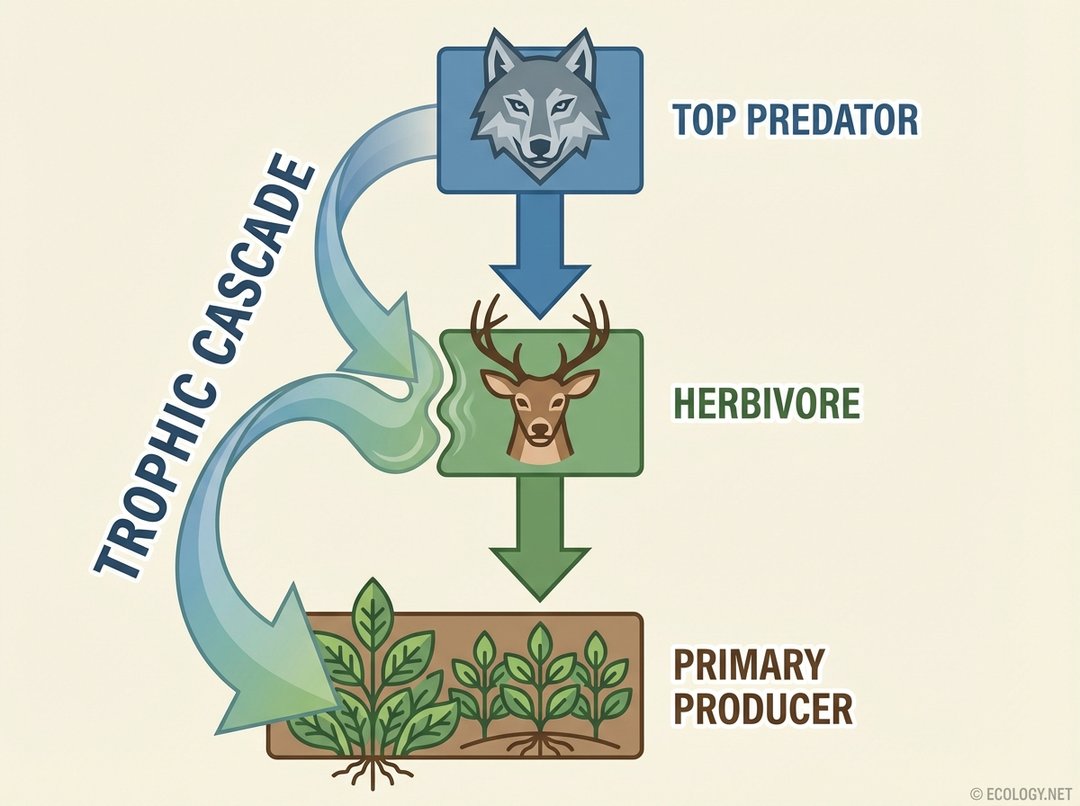

A trophic cascade describes an ecological phenomenon triggered by the addition or removal of top predators, which then ripples downwards through the food web, affecting the abundance of populations at successively lower trophic levels. It is a powerful demonstration of how changes at one level of an ecosystem can have profound and often surprising effects on others, sometimes transforming entire landscapes.

What are Trophic Cascades? Unpacking the Ecological Ripple Effect

To understand a trophic cascade, we first need to grasp the concept of trophic levels. These are the different feeding positions in a food chain or food web. Think of it like a pyramid:

- Primary Producers: At the base, these are organisms like plants and algae that create their own food, usually through photosynthesis.

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): These are organisms that feed on primary producers, such as deer grazing on grass or rabbits eating leaves.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores/Omnivores): These organisms feed on primary consumers, like a wolf hunting a deer.

- Tertiary Consumers (Apex Predators): At the top, these predators feed on secondary consumers and often have no natural predators themselves, such as a killer whale preying on seals.

A trophic cascade occurs when a change at one of these levels, particularly at the top, sets off a chain reaction that alters the populations at lower levels. Most commonly, this involves a top-down cascade, where predators suppress the abundance or alter the behavior of their prey, thereby releasing the next lower trophic level from predation or herbivory. This can lead to dramatic shifts in ecosystem structure and function.

The impact of a trophic cascade is not always about direct consumption. Predators can also influence their prey through non-consumptive effects, such as instilling fear that changes prey behavior, foraging patterns, or habitat use. This behavioral shift can be just as impactful as direct predation in shaping the ecosystem below.

Classic Examples: Where Trophic Cascades Reshaped Ecosystems

The concept of trophic cascades might seem abstract, but the natural world provides compelling, real-world examples that vividly illustrate its power.

Yellowstone National Park: The Return of the Wolves

Perhaps the most famous and well-studied example of a trophic cascade unfolded in Yellowstone National Park. For decades, wolves, the park’s apex predators, were hunted to extinction in the region by the 1920s. Their absence had a profound and unforeseen impact on the ecosystem.

- Wolves Absent: Without wolves, the elk population grew unchecked. These abundant herbivores heavily grazed on young willow and aspen trees, particularly along riverbanks. This overgrazing led to a significant decline in riparian vegetation, which in turn caused riverbanks to erode, streams to widen, and water temperatures to rise. The loss of these trees also meant less habitat for birds and beavers, and the ecosystem began to degrade.

- Wolves Present: In 1995, wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone. The impact was almost immediate and far-reaching. While wolves did prey on elk, their most significant effect was behavioral. Elk began to avoid vulnerable areas, such as river valleys and gorges, where they were more susceptible to predation. This shift in behavior allowed the overgrazed willow and aspen trees to recover and flourish.

The recovery of riparian vegetation had a cascade of positive effects. Beavers, which rely on willows for food and dam building, returned to the park. Their dams created new wetlands, providing habitat for otters, muskrats, and waterfowl. The stabilized riverbanks reduced erosion, leading to clearer, colder water, which benefited fish populations. Even scavenger species like bears and eagles benefited from wolf kills. The reintroduction of a single species, the wolf, effectively revitalized an entire ecosystem, demonstrating the immense power of a trophic cascade.

Kelp Forests: Sea Otters and Urchin Barrens

Another compelling example of a trophic cascade occurs in the marine environment, specifically in the vibrant kelp forests along the Pacific coast.

- The Role of Sea Otters: Sea otters are a keystone species in these ecosystems, meaning their presence has a disproportionately large effect on their environment relative to their abundance. Their primary food source is sea urchins, which are voracious grazers of kelp.

- Otters Absent, Urchins Abundant: Historically, sea otter populations were decimated by fur hunting. Without their main predator, sea urchin populations exploded. These unchecked urchins grazed relentlessly on kelp, converting lush kelp forests into barren seafloors known as urchin barrens. These barrens are ecological deserts, supporting far less biodiversity than healthy kelp forests.

- Otters Present, Kelp Thriving: Where sea otter populations have recovered, they keep sea urchin numbers in check. This allows kelp forests to grow tall and dense, providing critical habitat, food, and shelter for a vast array of marine life, including fish, invertebrates, and other marine mammals. The kelp forests also play a crucial role in carbon sequestration and protecting coastlines from erosion.

The kelp forest example highlights how the health of an entire underwater ecosystem hinges on the presence of a single predator, illustrating the fragility and interconnectedness of marine food webs.

The Broader Ecological Significance: Beyond Simple Food Chains

The implications of trophic cascades extend far beyond simply understanding who eats whom. They reveal fundamental truths about ecosystem resilience, biodiversity, and even the physical structure of landscapes.

Ecosystem Engineers and Biodiversity Boosters

Top predators, through trophic cascades, can act as ecosystem engineers. By influencing herbivore populations and plant communities, they indirectly shape the physical environment. In Yellowstone, the wolves’ influence on elk behavior led to the recovery of riparian trees, which in turn stabilized riverbanks and created new beaver ponds. These physical changes fundamentally altered the landscape and created new habitats.

Trophic cascades often lead to an increase in biodiversity. By controlling dominant herbivores, predators can prevent a few plant species from being overgrazed, allowing a wider variety of plant life to thrive. This increased plant diversity then supports a greater diversity of insects, birds, and other animals, enriching the entire ecosystem.

Ecosystem Services and Human Well-being

The health of ecosystems, often influenced by trophic cascades, directly impacts the ecosystem services that benefit humanity. For instance:

- Water Quality: Healthy riparian vegetation, restored by cascades, filters water, reduces erosion, and maintains cooler stream temperatures, benefiting aquatic life and human water supplies.

- Carbon Sequestration: Thriving plant communities, whether forests or kelp beds, absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, playing a role in climate regulation.

- Soil Stability: Reduced overgrazing leads to healthier soils, preventing erosion and supporting agricultural productivity.

Understanding these cascades is crucial for conservation efforts. It underscores the importance of protecting apex predators, not just for their intrinsic value, but for their vital role in maintaining the health and stability of entire ecosystems. Reintroducing predators, as seen in Yellowstone, can be a powerful tool for ecological restoration, though it often comes with complex social and political challenges.

Challenges and Nuances in Trophic Cascade Research

While the concept of trophic cascades is powerful, it is important to acknowledge its complexities and nuances:

- Context Dependency: Not all ecosystems exhibit strong trophic cascades. The strength of a cascade can depend on factors like the number of trophic levels, the productivity of the ecosystem, the presence of alternative prey, and the specific species involved.

- Human Impacts: Human activities, such as habitat fragmentation, pollution, and climate change, can disrupt or mask trophic cascades, making them harder to detect or predict. For example, hunting pressure on herbivores might mimic the effect of natural predators, but without the full suite of ecological interactions.

- Complexity of Food Webs: Real-world food webs are incredibly complex, with many species interacting in myriad ways. Isolating a single cascade effect can be challenging, as multiple factors often influence population dynamics simultaneously.

Despite these complexities, the study of trophic cascades continues to provide invaluable insights into the intricate workings of nature, reminding us that every species, from the smallest microbe to the largest predator, plays a role in the grand ecological drama.

Conclusion: The Interconnected Tapestry of Life

Trophic cascades offer a compelling narrative of nature’s interconnectedness, demonstrating that the removal or reintroduction of a single species, particularly an apex predator, can send ripples of change throughout an entire ecosystem. From the towering forests of Yellowstone to the swaying kelp beds of the Pacific, these ecological phenomena highlight the profound influence of top-down control on biodiversity, ecosystem health, and the vital services that support all life on Earth.

By understanding trophic cascades, we gain a deeper appreciation for the delicate balance of nature and the critical importance of conserving every thread in life’s intricate tapestry. It is a powerful reminder that in ecology, nothing truly exists in isolation; every action, every presence, every absence, reverberates throughout the living world.