Unveiling the Hidden Layers: A Deep Dive into Thermal Stratification

Imagine a lake, seemingly still and uniform on the surface. Beneath that calm exterior, however, a complex dance of temperatures and densities unfolds, profoundly shaping the aquatic world within. This invisible architecture is known as thermal stratification, a fundamental ecological process that dictates everything from oxygen levels to nutrient availability, ultimately influencing the very life that thrives in our freshwater ecosystems. Understanding thermal stratification is key to appreciating the intricate balance of lakes and how they respond to environmental changes.

What is Thermal Stratification? The Lake’s Invisible Architecture

At its heart, thermal stratification is the layering of lake water into distinct temperature zones. This phenomenon occurs because water density changes with temperature. Unlike most liquids, water is densest at approximately 4°C (39.2°F). As it warms above or cools below this point, it becomes less dense. This unique property allows warmer, lighter water to float atop cooler, denser water, creating a stable layering effect.

A thermally stratified lake typically develops three primary layers during warmer months:

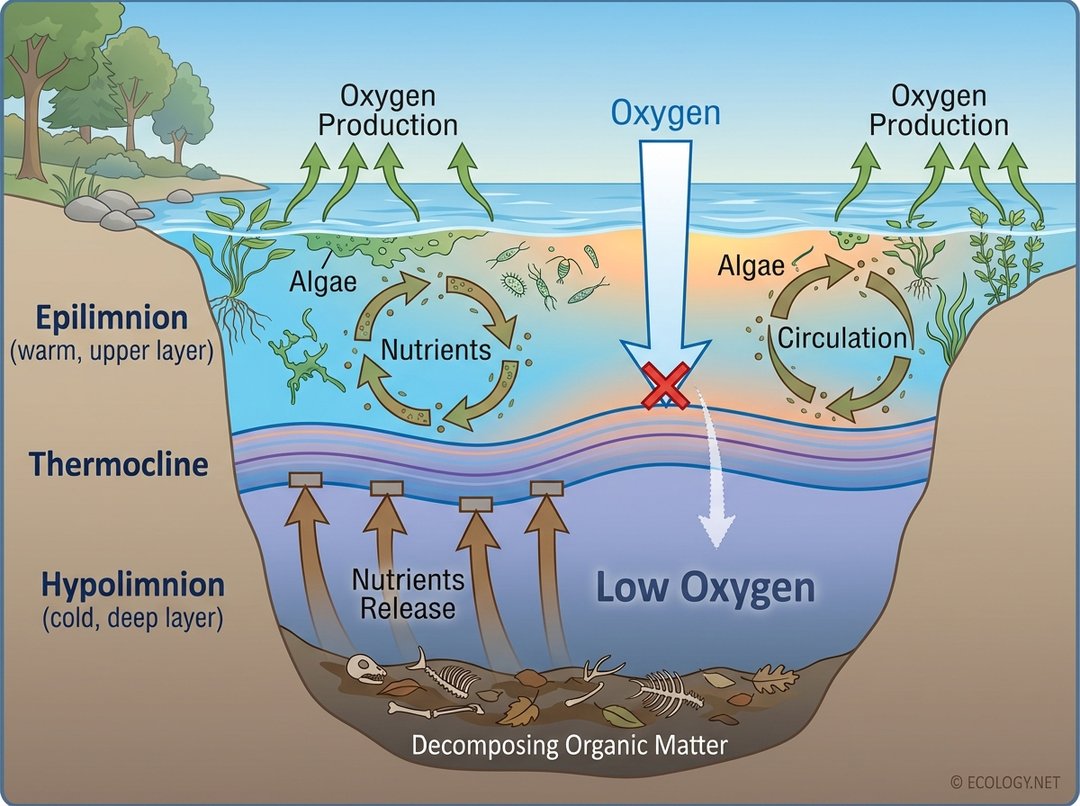

- Epilimnion: This is the warm, well-mixed upper layer of the lake. Exposed to sunlight and wind, it’s typically the warmest and most oxygenated zone, teeming with photosynthetic organisms like algae and aquatic plants.

- Thermocline (or Metalimnion): Situated beneath the epilimnion, the thermocline is a transitional layer characterized by a rapid decrease in temperature with increasing depth. It acts as a crucial barrier, significantly limiting the exchange of water, oxygen, and nutrients between the upper and lower layers.

- Hypolimnion: The deepest and coldest layer of the lake, the hypolimnion remains relatively stable and isolated from the surface. Due to its isolation, it often experiences low oxygen levels, especially in productive lakes where decomposition consumes available oxygen.

This layered structure, particularly the impermeable nature of the thermocline, has profound ecological consequences, dictating where life can flourish and where conditions become challenging.

Ecological Consequences: Oxygen, Nutrients, and Aquatic Life

The formation of these distinct layers has far-reaching implications for the lake’s ecosystem.

Oxygen Availability

The epilimnion, being exposed to the atmosphere and sunlight, is typically rich in oxygen due to atmospheric diffusion and photosynthesis by aquatic plants and algae. However, the thermocline acts as a formidable barrier, preventing this oxygen-rich water from easily mixing with the deeper layers. In the hypolimnion, away from light and atmospheric exchange, oxygen is primarily consumed by the decomposition of organic matter that sinks from the epilimnion. This often leads to a significant depletion of oxygen in the hypolimnion, creating hypoxic (low oxygen) or even anoxic (no oxygen) conditions. Such conditions can be detrimental, or even lethal, to fish and other aquatic organisms that require oxygen to survive.

Nutrient Distribution

Just as oxygen is trapped in the upper layer, nutrients can become trapped in the lower layer. Organic matter, rich in nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen, sinks from the epilimnion to the hypolimnion. As this matter decomposes, these nutrients are released into the hypolimnion. However, the thermocline prevents these newly released nutrients from circulating back up to the epilimnion where they could fuel primary production. This can lead to a paradox: the upper layer, where light is abundant, may become nutrient-limited, while the deeper layer accumulates nutrients that are inaccessible to surface-dwelling producers.

Impact on Aquatic Life

The varying conditions across the stratified layers create distinct habitats. Fish species, for instance, may migrate vertically to find optimal temperatures and oxygen levels. Cold-water fish like trout might seek refuge in the cooler, deeper waters during summer, but only if sufficient oxygen is present. Organisms adapted to low oxygen environments, such as certain bacteria and invertebrates, might dominate the hypolimnion. Severe oxygen depletion can lead to fish kills and a reduction in biodiversity, particularly in the deeper parts of the lake.

The Dynamic Nature: Seasonal Lake Turnover

Thermal stratification is not a static condition; it is a dynamic process that changes with the seasons, leading to periods of mixing known as “turnover.” This seasonal cycle is vital for the health of the lake, allowing for the redistribution of oxygen and nutrients.

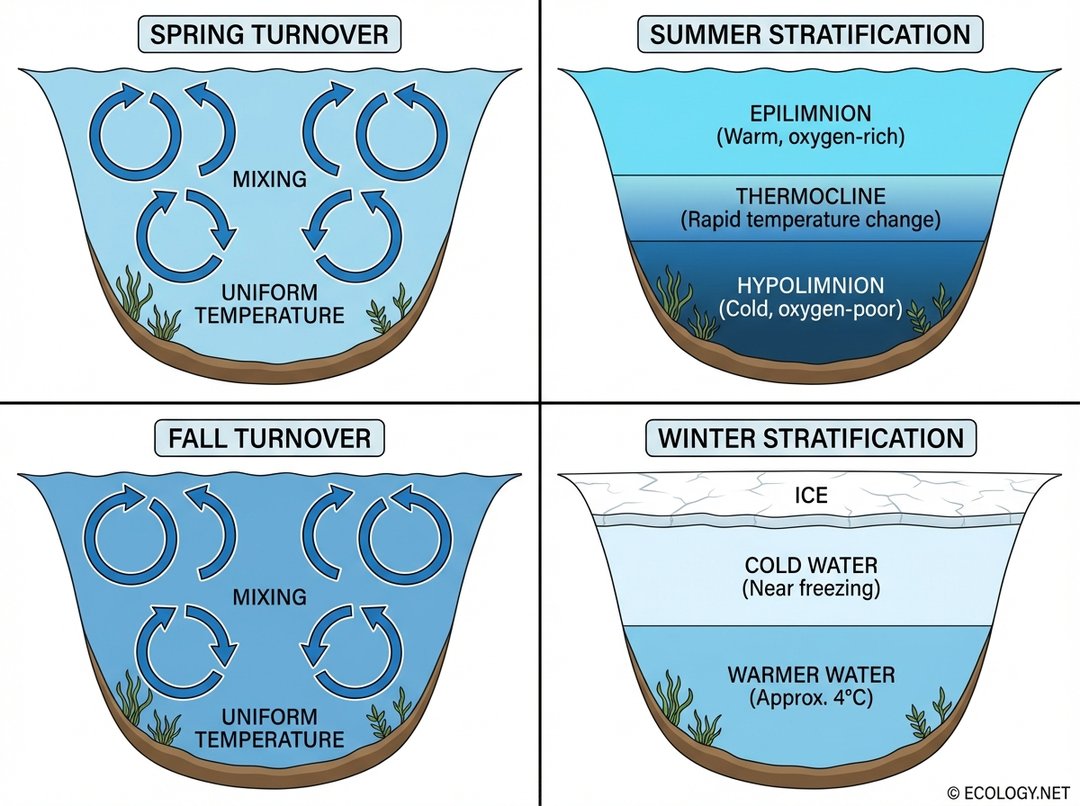

The typical seasonal cycle in temperate lakes includes:

- Spring Turnover: As winter ice melts and surface waters warm to approximately 4°C, the entire water column reaches a uniform temperature and density. Wind action can then easily mix the entire lake from top to bottom, bringing oxygen to the depths and nutrients to the surface.

- Summer Stratification: With increasing solar radiation, the surface waters warm significantly, becoming less dense than the deeper, cooler waters. This leads to the stable stratification described earlier, with a distinct epilimnion, thermocline, and hypolimnion.

- Fall Turnover: As autumn arrives, surface waters cool, becoming denser. Eventually, the surface water temperature drops to match the deeper water, allowing wind to once again mix the entire lake. This “fall turnover” replenishes deep-water oxygen and redistributes nutrients throughout the water column.

- Winter Stratification: In colder climates, as surface water cools below 4°C, it becomes less dense and freezes, forming a layer of ice. Water just beneath the ice will be near 0°C, while the densest water (around 4°C) settles at the bottom. This creates an “inverse stratification,” with colder water above warmer water, and the lake remains largely unmixed until spring.

This cyclical mixing is crucial for maintaining the overall health and productivity of the lake, preventing prolonged periods of anoxia and nutrient limitation.

Factors Influencing Stratification

Several factors determine the strength and duration of thermal stratification in a lake:

- Lake Depth and Size: Deeper lakes with larger volumes are more prone to strong and persistent stratification because they have a greater capacity to store heat and resist mixing. Shallow lakes, conversely, may mix more frequently or remain unstratified.

- Climate and Weather Patterns: Warmer climates and prolonged periods of calm, sunny weather promote stronger and longer-lasting stratification. Windy conditions, on the other hand, can help break down stratification by increasing surface mixing.

- Wind Exposure: Lakes exposed to strong, consistent winds are more likely to mix thoroughly, even during warmer periods, reducing the stability of stratification. Sheltered lakes, surrounded by hills or forests, tend to stratify more readily.

- Water Clarity/Turbidity: Clear water allows sunlight to penetrate deeper, warming a larger volume of water and potentially strengthening stratification. Turbid water absorbs more solar radiation closer to the surface, concentrating heat in the epilimnion and potentially enhancing stratification.

Human Impact and Management

Human activities can significantly alter and exacerbate the effects of thermal stratification.

Eutrophication, the excessive enrichment of a lake with nutrients (often from agricultural runoff or wastewater), can intensify stratification’s negative impacts. Increased nutrient loads fuel algal blooms in the epilimnion. When these algae die and sink, their decomposition in the hypolimnion consumes even more oxygen, leading to more severe and widespread anoxia. This creates a vicious cycle, where nutrient release from anoxic sediments further fuels surface blooms.

Climate change also plays a role. Warmer air temperatures can lead to earlier onset of stratification, stronger thermoclines, and longer periods of stratification, potentially extending the duration of low-oxygen conditions in the hypolimnion.

Management strategies often focus on mitigating these human impacts:

- Nutrient Reduction: Controlling nutrient inputs from surrounding land is paramount to preventing eutrophication and its associated oxygen depletion.

- Aeration: In some cases, mechanical aeration systems are used to pump air into the hypolimnion or circulate water, artificially breaking down stratification and increasing oxygen levels.

- Hypolimnetic Withdrawal: For lakes with severe deep-water anoxia and nutrient accumulation, withdrawing water from the hypolimnion can remove nutrient-rich, low-oxygen water, though this requires careful management.

Conclusion: The Unseen Engine of Lake Health

Thermal stratification is far more than just a temperature gradient; it is a fundamental physical process that acts as an unseen engine, driving the ecological dynamics of lakes. From the vibrant life in the sunlit epilimnion to the often-challenging conditions of the deep hypolimnion, this layering profoundly influences oxygen availability, nutrient cycling, and the distribution of aquatic organisms. The seasonal dance of turnover ensures the periodic rejuvenation of these vital freshwater bodies. By understanding the intricacies of thermal stratification and its susceptibility to human influence, we can better appreciate the delicate balance of lake ecosystems and work towards their sustainable management and conservation for generations to come.