The Ever-Changing Earth: Understanding Ecological Succession

Imagine a world where nothing stays the same, where landscapes are constantly evolving, transforming from barren rock to lush forest, or from a scorched wasteland to a vibrant ecosystem. This dynamic process, fundamental to life on Earth, is known as ecological succession. It is the gradual and predictable change in the species structure of an ecological community over time, a testament to nature’s incredible resilience and adaptability.

Ecological succession is not a sudden event, but a slow, methodical dance of life, driven by interactions between organisms and their environment. It explains how new land is colonized and how disturbed areas recover, shaping the biodiversity and stability of our planet’s ecosystems.

What is Ecological Succession?

At its core, ecological succession describes the sequence of changes in an ecological community following a disturbance or the creation of new habitat. Think of it as nature’s way of rebuilding or establishing life where it once struggled or never existed. This process involves a series of stages, each characterized by different plant and animal species, gradually leading towards a more stable and complex community.

The journey of succession often begins with hardy, fast-growing species, known as pioneer species, which modify the environment, making it suitable for other species to follow. These subsequent species then outcompete the pioneers, further altering the habitat, and the cycle continues until a relatively stable community, often referred to as a climax community, is established.

Two Paths to Renewal: Primary and Secondary Succession

Ecologists categorize succession into two main types, distinguished by their starting conditions:

Primary Succession: Building from Scratch

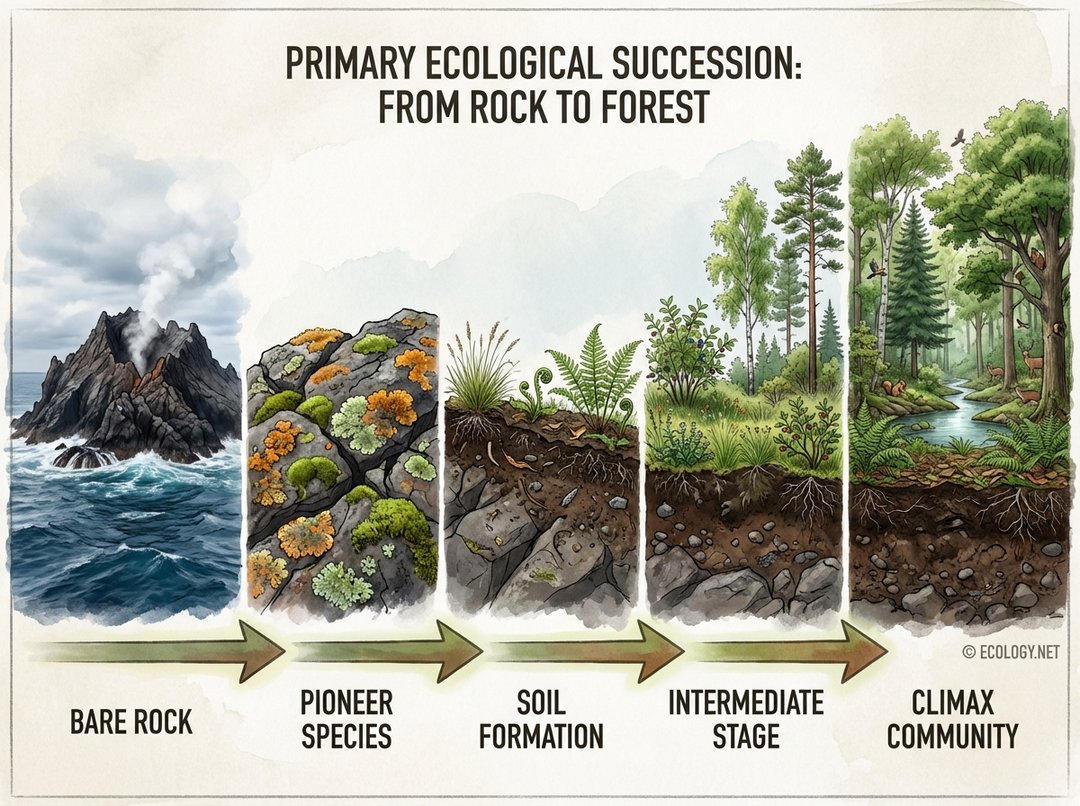

Primary succession occurs in environments where new substrate, or bare ground, is created, devoid of any existing life or soil. This can happen after events like volcanic eruptions forming new islands, the retreat of glaciers exposing bare rock, or sand dune formation. In these harsh, lifeless environments, the process of establishing an ecosystem is incredibly challenging and slow.

The first colonizers in primary succession are often microscopic organisms, followed by tough, resilient species like lichens and mosses. These pioneer species play a crucial role. Lichens, for instance, can grow directly on bare rock, slowly breaking it down through chemical and physical weathering. As they grow and die, they contribute organic matter, beginning the painstaking process of soil formation. This nascent soil, though thin and nutrient-poor, eventually allows small grasses and ferns to take root. Over centuries, or even millennia, this continues, with larger plants, shrubs, and eventually trees colonizing the area, leading to a mature forest.

A classic example of primary succession can be observed on newly formed volcanic islands, such as those in Hawaii. Lava flows cool to form barren rock, which is then slowly colonized by lichens, mosses, and eventually a diverse array of plant and animal life, transforming the stark landscape into a vibrant ecosystem.

Secondary Succession: Nature’s Rebound

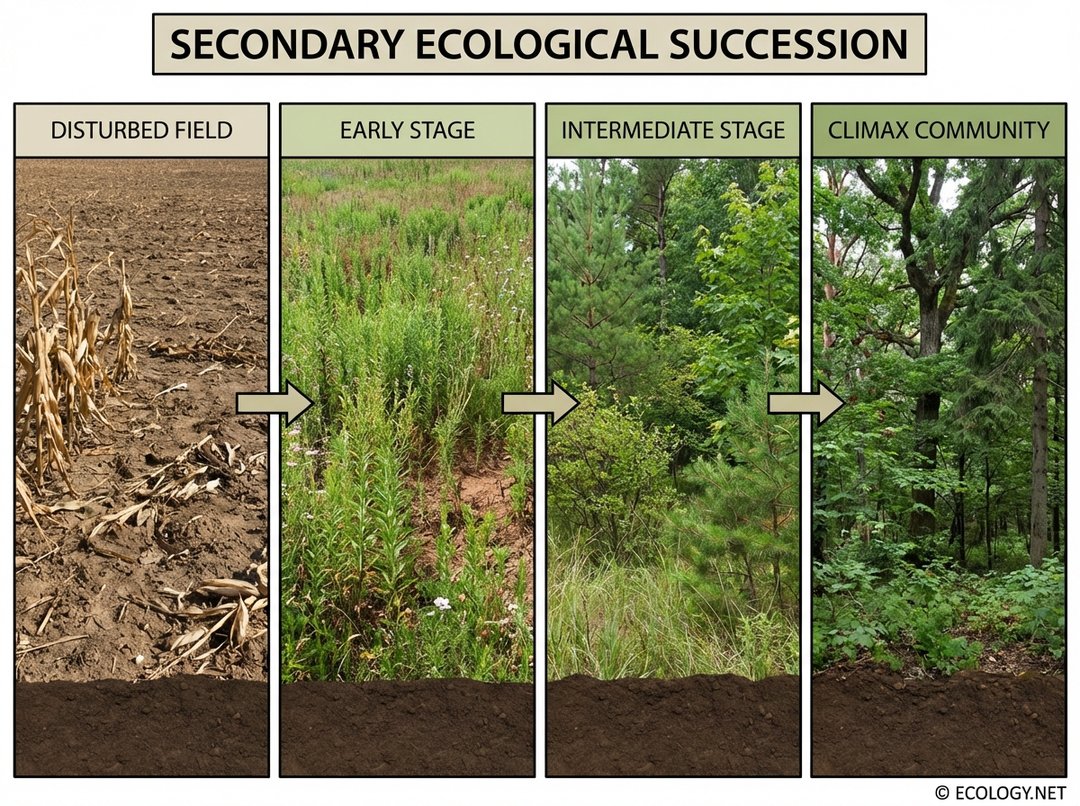

In contrast, secondary succession occurs in areas where a community has been removed or disturbed, but the soil or substrate remains intact. This process is generally much faster than primary succession because the foundation for life, the soil, is already present and often contains seeds, spores, and surviving root systems.

Common triggers for secondary succession include natural disasters like forest fires, floods, hurricanes, or human activities such as logging, farming, or land abandonment. Imagine a forest ravaged by fire. While the trees are gone, the nutrient-rich ash and existing soil provide a fertile ground for rapid regrowth. Within weeks or months, fast-growing weeds and grasses emerge, followed by shrubs and small trees. Over decades, these give way to larger, longer-lived tree species, eventually restoring the forest community.

Abandoned agricultural fields provide another excellent illustration. Once farming ceases, the field is quickly colonized by annual weeds, then perennial grasses and wildflowers, followed by shrubs like sumac and blackberry, and finally, pioneer tree species like pines or poplars. This progression eventually leads to a mature deciduous forest, if left undisturbed.

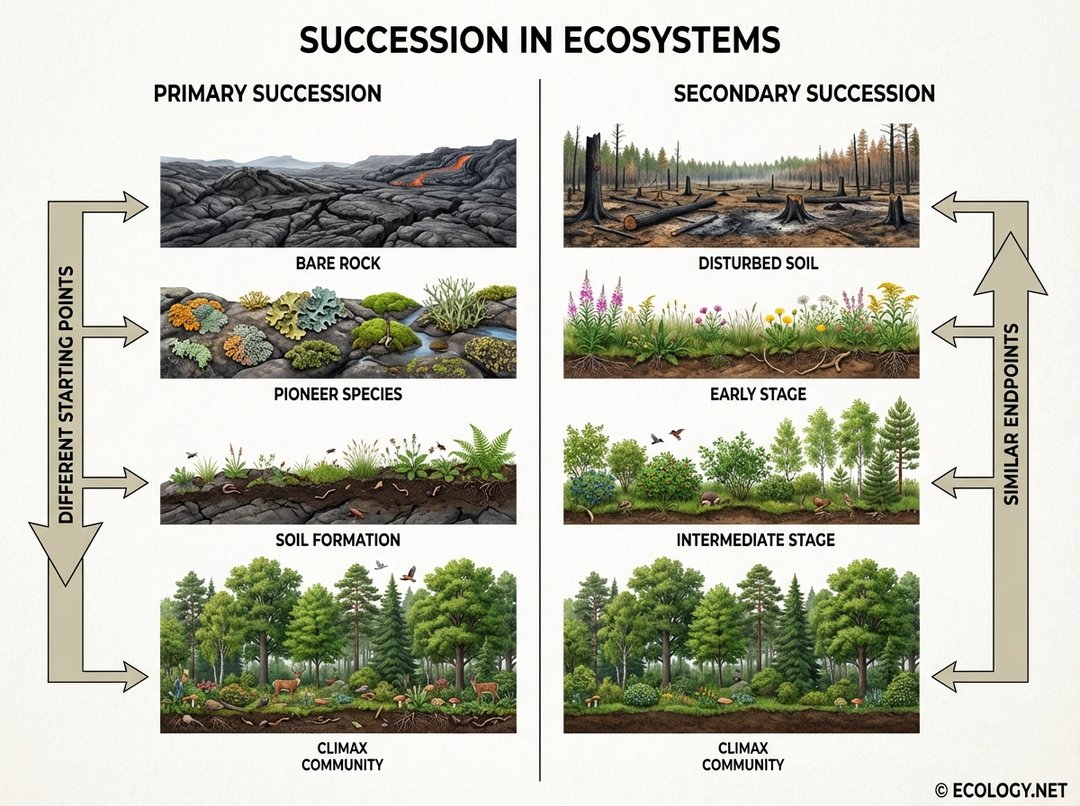

Comparing the Two: Different Beginnings, Similar Endpoints

While primary and secondary succession differ significantly in their starting points and the speed of their progression, they often share a common trajectory towards a stable, mature ecosystem. The key distinction lies in the presence or absence of soil at the outset.

- Primary Succession: Starts with bare rock or new substrate, no existing soil. It is a slow process, often taking hundreds to thousands of years.

- Secondary Succession: Starts with existing soil after a disturbance. It is a much faster process, typically taking decades to a few centuries.

Both types of succession involve a series of transitional communities, known as seral stages, each characterized by a dominant set of species. Despite their different origins, both pathways can ultimately lead to a climax community, a relatively stable and self-perpetuating ecosystem that is in equilibrium with its environment.

The Unsung Heroes: Pioneer Species and Their Transformative Role

The initial colonizers in any successional sequence, the pioneer species, are truly remarkable. These organisms are adapted to harsh conditions, capable of surviving with minimal resources and often playing a critical role in modifying the environment for subsequent species.

- Lichens and Mosses: In primary succession, these organisms can withstand extreme temperatures and lack of nutrients. They secrete acids that help break down rock, and their decaying bodies contribute organic matter, slowly building the first layers of soil.

- Grasses and Weeds: In secondary succession, species like dandelions, ragweed, and various grasses are often the first to appear. They grow quickly, have efficient seed dispersal mechanisms, and can stabilize soil, preventing erosion and adding organic material.

Pioneer species are not just survivors; they are ecosystem engineers. They alter soil composition, increase moisture retention, provide shade, and create microclimates, making the environment progressively more hospitable for a wider array of life forms. This environmental modification is a driving force behind the entire successional process.

From Seral Stages to Climax Communities: A Dynamic Equilibrium

As succession progresses, the community moves through various seral stages. Each stage sees a shift in dominant species, often from small, fast-growing plants to larger, slower-growing ones, and a corresponding change in animal life. Biodiversity often increases during the intermediate stages, as a mix of early and late successional species coexist.

The concept of a climax community refers to the final, relatively stable stage of succession. This community is characterized by:

- High biodiversity and complex food webs.

- Dominance by long-lived, shade-tolerant species (e.g., mature trees in a forest).

- A relatively stable biomass and nutrient cycling.

- Self-perpetuation, meaning it can reproduce and maintain itself without significant external disturbance.

However, it is important to understand that a climax community is not static. It is a state of dynamic equilibrium. Small disturbances, like individual tree falls or minor fires, are natural parts of these ecosystems and can create patches of earlier successional stages within the overall climax community, contributing to its overall diversity and resilience. The idea of a single, permanent climax community has evolved; ecologists now often speak of a “climax pattern” or “shifting mosaic” where the community is stable on a larger scale but constantly changing at a smaller, local level.

Factors Influencing the Pace and Path of Succession

While the general principles of succession are universal, the specific species involved and the speed of the process can vary greatly depending on several factors:

- Climate: Temperature, rainfall, and seasonality dictate which species can survive and thrive. A tropical rainforest will undergo succession very differently from a tundra environment.

- Topography: Slope, aspect (direction a slope faces), and elevation influence sunlight, moisture, and soil development, thereby affecting successional pathways.

- Disturbance Regime: The frequency, intensity, and type of disturbance (e.g., frequent small fires versus rare catastrophic ones) play a significant role in resetting or altering successional trajectories.

- Species Availability: The presence of nearby seed sources, animal dispersers, and colonizing organisms is crucial for the progression of succession.

- Soil Characteristics: For secondary succession, the existing soil’s nutrient content, pH, and structure greatly influence which species can establish first.

Succession in Action: Real-World Examples

Understanding succession helps us interpret the landscapes around us:

- Mount St. Helens: The eruption in 1980 devastated vast areas, creating a living laboratory for primary and secondary succession. Bare rock and ash fields are slowly being colonized, while areas with surviving soil are recovering much faster.

- Glacier Bay, Alaska: As glaciers retreat, they expose newly deglaciated land, offering a clear view of primary succession from bare rock to spruce and hemlock forests over centuries.

- Coral Reefs: While often overlooked, coral reefs also undergo succession. After a disturbance like a hurricane or coral bleaching event, new corals and other marine organisms colonize the damaged areas, slowly rebuilding the complex reef structure.

The Ecological Importance and Human Relevance of Succession

The study of ecological succession is far more than an academic exercise; it has profound implications for environmental management and conservation:

- Biodiversity Conservation: Understanding successional stages helps conservationists manage habitats to support a diverse range of species, some of which thrive in early successional stages, while others require mature climax communities.

- Restoration Ecology: Knowledge of succession is critical for restoring degraded ecosystems. By mimicking natural successional processes, ecologists can guide the recovery of wetlands, forests, and other habitats.

- Ecosystem Resilience: Succession demonstrates the incredible resilience of ecosystems, their ability to recover and adapt after significant disturbances. This understanding is vital in an era of increasing environmental change.

- Resource Management: In forestry, for example, understanding succession helps in sustainable timber harvesting practices, ensuring forest regeneration.

- Climate Change: Succession patterns can be altered by climate change, as shifts in temperature and precipitation favor different species and influence disturbance regimes. Studying these changes is crucial for predicting future ecosystem states.

Ecological succession is a powerful reminder that nature is not static. It is a continuous, dynamic process of change, adaptation, and renewal. From the first intrepid lichens on bare rock to the towering trees of a mature forest, every stage of succession tells a story of life’s enduring capacity to transform and thrive. By observing and understanding these natural rhythms, we gain deeper insights into the intricate web of life and our own place within it.