Soil, the very foundation beneath our feet, is far more than just dirt. It is a living, breathing ecosystem, a complex matrix of minerals, organic matter, water, air, and countless organisms. This thin, vital layer supports nearly all life on Earth, providing nutrients for plants, filtering water, and regulating climate. Yet, this precious resource faces a relentless, often unseen threat: soil erosion. Understanding this silent adversary is crucial for safeguarding our planet’s future and ensuring food security for generations to come.

What is Soil Erosion? The Unseen Disappearance

Soil erosion is the natural process by which the top layer of soil, known as topsoil, is displaced from one location to another. While a certain degree of erosion occurs naturally as part of geological processes, human activities have dramatically accelerated its pace, turning a slow, regenerative cycle into a rapid, destructive force. This accelerated erosion leads to significant land degradation, diminishing the soil’s fertility and its capacity to support life.

Think of topsoil as the Earth’s skin. It is the most fertile part of the soil, rich in organic matter and nutrients essential for plant growth. When this layer is stripped away, what remains is often less productive subsoil, leading to a cascade of environmental and economic problems.

The Mechanics of Loss: How Soil Vanishes

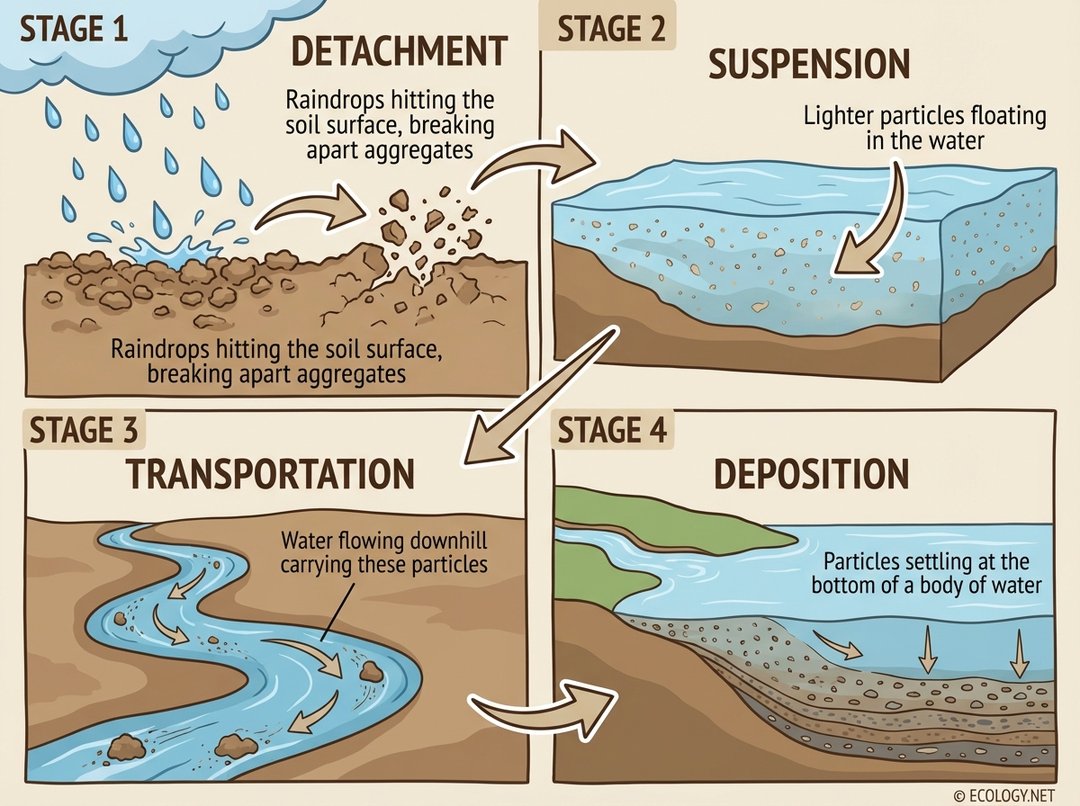

To truly grasp the impact of soil erosion, it is helpful to understand the fundamental stages through which it occurs. Water, a primary agent of erosion, orchestrates a four part process:

- Detachment: This initial stage begins with the impact of raindrops hitting the bare soil surface. The force of these tiny projectiles breaks apart soil aggregates, dislodging individual soil particles. Imagine countless miniature explosions on the soil, freeing particles from their cohesive bonds.

- Suspension: Once detached, lighter soil particles, particularly fine silt and clay, become suspended in the water. They are too light to settle immediately and remain afloat, ready to be carried away by flowing water.

- Transportation: As water flows across the land, whether as a thin sheet or concentrated in channels, it carries the suspended and detached soil particles downhill. The speed and volume of the water dictate how much soil can be transported and how far it will travel.

- Deposition: Eventually, as the water loses energy, perhaps by slowing down or entering a larger body of water, the transported soil particles settle out. This deposition can occur in rivers, lakes, reservoirs, or on lower lying land, often accumulating as sediment.

This sequential process, from the initial impact to the final resting place of the soil particles, illustrates the journey of valuable topsoil as it is lost from productive land.

The Many Faces of Water Erosion

While the four stages describe the general mechanism, water erosion manifests in several distinct forms, each with its own characteristics and level of severity. These forms often progress from subtle to devastating:

- Raindrop Erosion (Splash Erosion): This is the first stage of water erosion. Individual raindrops strike the soil surface, dislodging particles and splashing them into the air. On bare soil, these splashes can move soil particles several feet, initiating the process of detachment.

- Sheet Erosion: When raindrops accumulate and form a thin, uniform layer of water flowing over the land surface, it is called sheet erosion. This flow subtly removes a uniform layer of topsoil, often unnoticed until significant damage has occurred. It is like peeling off a very thin layer of skin from the Earth.

- Rill Erosion: As sheet flow concentrates into small, well defined channels, rill erosion begins. These channels, typically only a few inches deep, are easily removed by normal tillage operations. However, if left unchecked, rills can deepen and widen.

- Gully Erosion: This is the most severe form of water erosion, occurring when rills coalesce and enlarge into deep, wide, and often permanent channels that cannot be erased by ordinary farm machinery. Gullies dissect fields, make land unusable, and transport vast quantities of soil downstream. They are stark indicators of severe land degradation.

Understanding these different forms helps in identifying the problem early and implementing appropriate conservation measures.

Beyond Water: Wind Erosion and Other Factors

While water is a dominant force, it is not the only agent of soil erosion. Wind also plays a significant role, particularly in arid and semi arid regions, or on large, open fields with dry, loose soil. Wind erosion occurs when strong winds lift and carry away fine soil particles, often leading to dust storms and the loss of fertile topsoil. Just like water erosion, wind erosion is exacerbated by human activities that leave soil bare and exposed.

Other factors that contribute to accelerated soil erosion include:

- Deforestation: Removing trees, especially on slopes, eliminates the protective canopy and root systems that hold soil in place, making it highly vulnerable to both wind and water.

- Overgrazing: Allowing livestock to graze too heavily on pastures can strip away vegetation, compact the soil, and leave it exposed.

- Unsustainable Agricultural Practices: Practices such as intensive tillage, monocropping, and farming on steep slopes without protective measures can severely degrade soil structure and increase erosion risk.

- Urbanization and Construction: Land clearing for development exposes vast areas of soil, making them susceptible to erosion before permanent structures or landscaping are established.

The Far Reaching Consequences of Soil Loss

The loss of topsoil is not merely an aesthetic problem; it triggers a cascade of negative impacts that affect ecosystems, economies, and human societies globally.

Environmental Impacts

- Reduced Soil Fertility: The most immediate impact is the loss of nutrient rich topsoil, leading to decreased agricultural productivity and requiring increased use of artificial fertilizers.

- Desertification: In severe cases, prolonged erosion can lead to desertification, transforming fertile land into barren wasteland incapable of supporting vegetation.

- Water Pollution and Sedimentation: Eroded soil particles carried into rivers and lakes increase turbidity, reduce water quality, and can smother aquatic habitats. Sedimentation fills reservoirs, reducing their capacity and lifespan.

- Habitat Loss: Erosion degrades natural landscapes, destroying habitats for countless plant and animal species, contributing to biodiversity loss.

- Increased Flooding: Degraded soils have a reduced capacity to absorb water, leading to increased surface runoff and a higher risk of flash floods.

Economic and Social Impacts

- Decreased Agricultural Yields: Farmers face reduced crop yields and higher input costs due to diminished soil fertility, impacting livelihoods and food security.

- Infrastructure Damage: Sedimentation can clog irrigation systems, damage roads, and reduce the navigability of waterways.

- Food Insecurity: Widespread soil degradation can threaten regional and global food supplies, leading to price increases and potential social unrest.

- Displacement and Migration: In extreme cases, land degradation can render areas uninhabitable, forcing communities to migrate in search of fertile land and resources.

Turning the Tide: Strategies for Soil Conservation

Fortunately, soil erosion is not an irreversible fate. A variety of effective conservation practices can mitigate its effects, protect existing soil, and even restore degraded land. These strategies often mimic natural processes or enhance the soil’s inherent resilience.

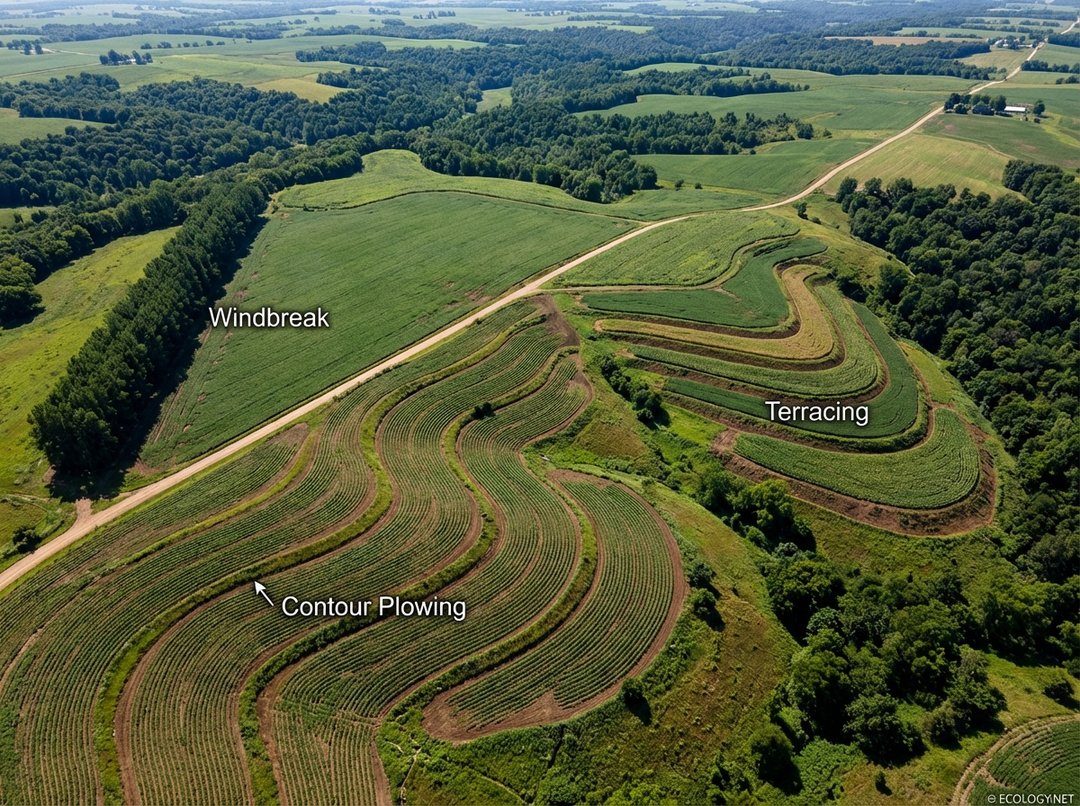

- Contour Plowing: Instead of plowing up and down a slope, farmers plow across it, following the natural contours of the land. These furrows act as miniature dams, slowing down water runoff and allowing it to infiltrate the soil rather than carrying it away.

- Terracing: On steeper slopes, terracing involves constructing a series of level platforms or steps. Each terrace acts as a barrier, intercepting water flow, reducing its velocity, and preventing soil movement downhill. This practice is common in mountainous agricultural regions.

- Cover Cropping: Planting non cash crops, such as legumes or grasses, during periods when the main crop is not growing helps protect the soil. Cover crops shield the soil from raindrop impact, improve soil structure, add organic matter, and suppress weeds.

- No Till and Minimum Tillage Farming: These practices reduce soil disturbance by minimizing or eliminating plowing. Crop residues are left on the surface, providing a protective layer that reduces erosion, conserves soil moisture, and enhances soil health.

- Windbreaks and Shelterbelts: Rows of trees or shrubs planted along field edges act as barriers against wind, reducing its speed and preventing wind erosion. They also provide habitat for wildlife and can enhance biodiversity.

- Riparian Buffers: Planting strips of vegetation along rivers, streams, and wetlands helps stabilize banks, filter runoff, and prevent soil from entering water bodies.

- Crop Rotation: Alternating different types of crops in a field over time helps maintain soil fertility, break pest cycles, and improve soil structure, making it more resistant to erosion.

Implementing a combination of these practices, tailored to specific local conditions, is key to effective soil conservation and sustainable land management.

A Deeper Dive: Understanding Erosion Rates and Measurement

For scientists and land managers, quantifying soil erosion is essential for effective planning and intervention. While complex, the principles involve understanding the factors that influence erosion rates.

One widely used tool is the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) and its revised version, RUSLE. These models estimate average annual soil loss based on factors such as rainfall intensity, soil erodibility, slope length and steepness, crop management practices, and support practices. While not perfect, they provide valuable insights into erosion potential and the effectiveness of different conservation measures.

Modern techniques also employ remote sensing and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to map and monitor erosion over large areas. Satellite imagery and aerial photography can detect changes in land cover, identify areas prone to erosion, and track the formation of rills and gullies, offering a powerful perspective on the scale and progression of soil loss.

Understanding these quantitative aspects allows for more precise targeting of conservation efforts, ensuring resources are allocated where they can have the greatest impact.

Conclusion: Our Collective Responsibility

Soil erosion is a profound environmental challenge, silently undermining the productivity of our land and the health of our ecosystems. From the gentle splash of a raindrop to the destructive force of a gully, the process of soil loss is a constant reminder of the delicate balance within nature and the significant impact of human activities.

However, the story of soil erosion is not one of despair. With knowledge, commitment, and the adoption of sustainable practices, we possess the tools to protect and restore this invaluable resource. By embracing conservation agriculture, responsible land management, and a deeper appreciation for the living soil beneath our feet, we can ensure that the Earth’s fertile skin remains intact, supporting life and prosperity for generations to come. The future of our planet, quite literally, depends on it.