The Eternal Dance: Unraveling the Complex World of Predation

Life on Earth is a constant interplay of forces, a magnificent tapestry woven from countless interactions. Among the most fundamental and dramatic of these interactions is predation. Far from being a simple act of one animal eating another, predation is a sophisticated ecological process that shapes species, drives evolution, and maintains the delicate balance of ecosystems across the globe. It is a story of survival, adaptation, and the relentless pursuit of sustenance, a narrative as old as life itself.

What is Predation? The Basic Definition

At its core, predation describes a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, hunts and kills another organism, its prey, for food. This interaction is a cornerstone of food webs, facilitating the transfer of energy from lower to higher trophic levels. While often conjuring images of a lion chasing a gazelle, the concept of predation extends far beyond this classic scenario, encompassing a surprising diversity of strategies and relationships. Understanding predation is crucial to grasping how ecosystems function and how life on our planet has evolved.

Beyond the Obvious: Diverse Forms of Predation

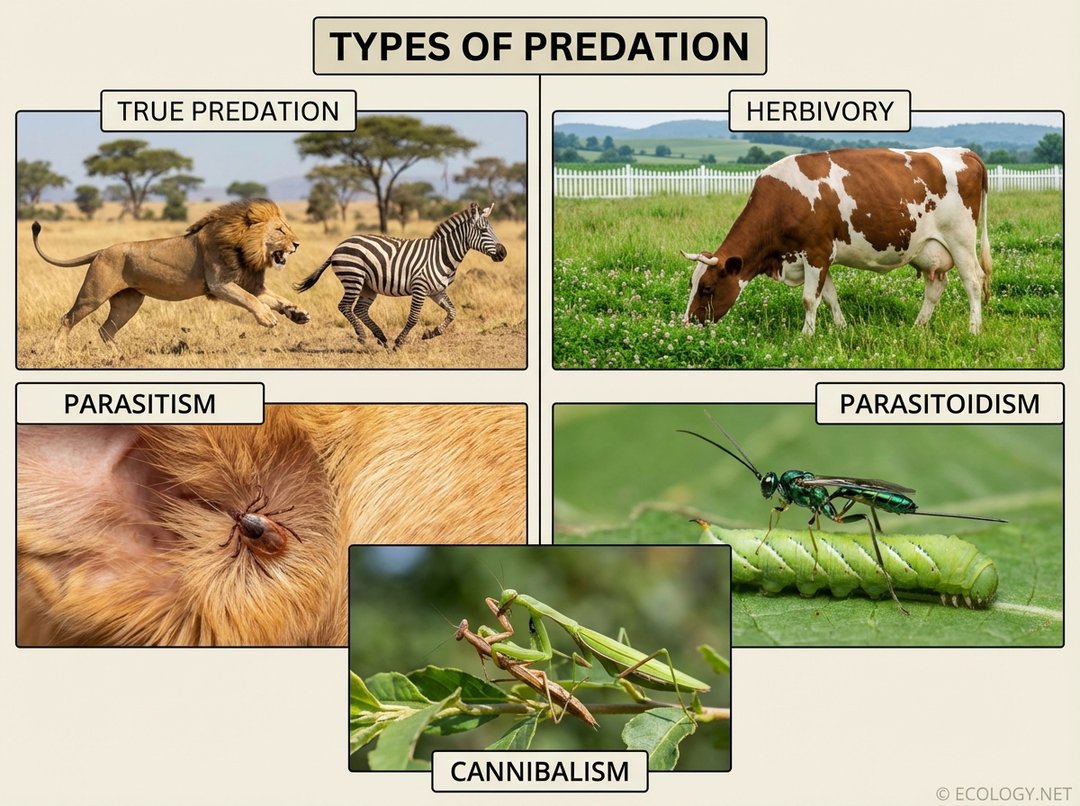

The term predation might seem straightforward, but the natural world reveals a spectrum of interactions that fall under this umbrella. These varied forms highlight the ingenuity of life in its quest for energy.

Let us explore some of the key types:

- True Predation: This is the most commonly recognized form, where a predator kills and consumes multiple prey individuals throughout its life. Examples include:

- Carnivory: A wolf hunting a deer.

- Omnivory: A bear eating berries and fish.

- Insectivory: A bird catching insects.

- Herbivory: Often considered a form of predation, herbivory involves an animal consuming plants or plant parts. While plants are not typically killed outright, their fitness is reduced.

- A cow grazing on grass.

- A caterpillar munching on leaves.

- A rabbit nibbling on clover.

- Parasitism: In this relationship, a parasite lives on or in a host organism, obtaining nutrients from it without immediately killing it. The host is typically harmed over time.

- A tick feeding on a dog’s blood.

- Tapeworms living in the intestines of mammals.

- Mistletoe growing on a tree, drawing water and nutrients.

- Parasitoidism: A fascinating and often gruesome form, parasitoidism involves an organism that lives in or on a host, eventually killing it. Unlike parasites, parasitoids typically kill their host as part of their life cycle.

- A parasitic wasp laying eggs inside a caterpillar, with the larvae consuming the caterpillar from within.

- Flies whose larvae develop inside other insects.

- Cannibalism: This occurs when an individual of a species preys on another individual of the same species. It is surprisingly common in the animal kingdom.

- A praying mantis consuming its mate.

- Polar bears preying on younger, smaller polar bears.

- Certain fish species eating their own offspring.

The Evolutionary Arms Race: A Dance of Survival

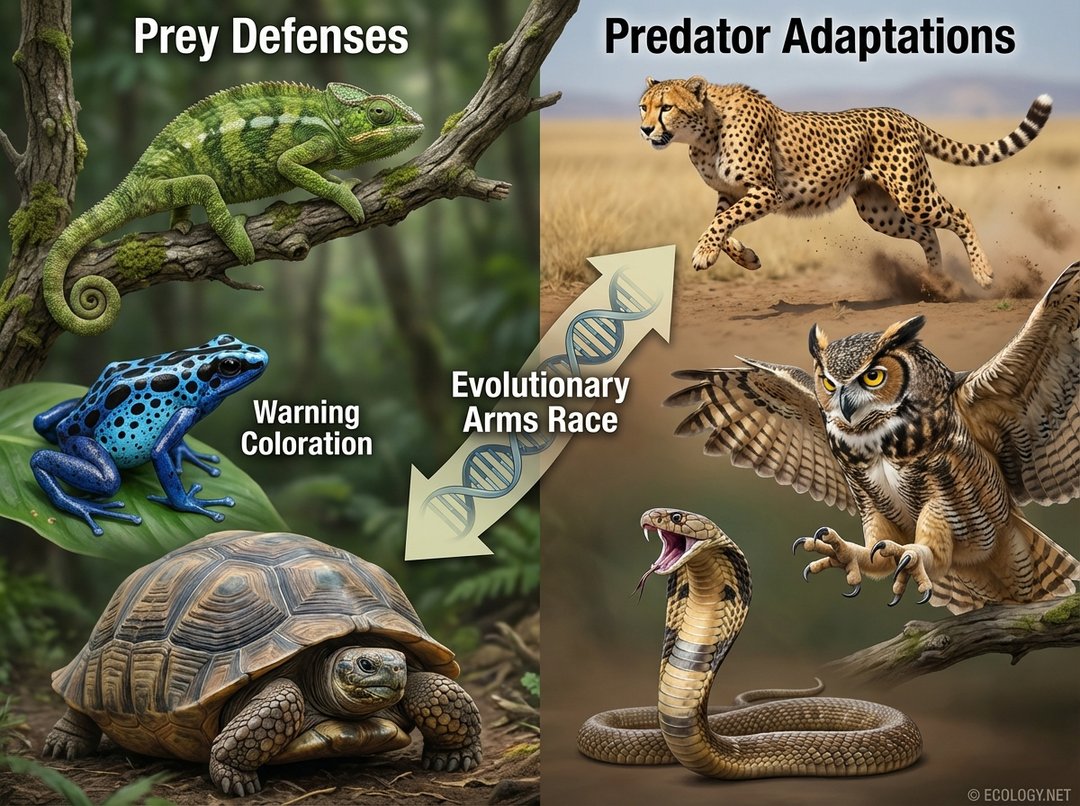

Predation is not a static interaction, but a dynamic, ongoing struggle that drives evolution. Over countless generations, predators and prey have engaged in a relentless “evolutionary arms race,” constantly adapting to outwit each other. This co-evolutionary process has resulted in some of the most remarkable features and behaviors observed in the natural world.

Prey Defenses: The Art of Evasion and Protection

Prey species have evolved an astonishing array of strategies to avoid being caught and eaten. These defenses can be broadly categorized:

- Physical Defenses:

- Armor: The hard shell of a turtle or armadillo.

- Spines/Thorns: The quills of a porcupine or the thorns on a rose bush.

- Size: Large body size can deter many predators.

- Chemical Defenses:

- Toxins/Poisons: The venom of a snake or the toxins in a poison dart frog.

- Repellents: Skunks spraying foul-smelling musk.

- Camouflage (Crypsis): Blending seamlessly with the environment to avoid detection.

- A chameleon changing color to match its surroundings.

- A stick insect mimicking a twig.

- A snowshoe hare’s fur turning white in winter.

- Mimicry: Evolving to resemble another species.

- Batesian Mimicry: A harmless species mimics a dangerous one, like a hoverfly resembling a bee.

- Müllerian Mimicry: Two or more unpalatable species resemble each other, like various species of wasps with similar black and yellow stripes.

- Warning Coloration (Aposematism): Bright, conspicuous colors that signal toxicity or danger to potential predators.

- The vibrant patterns of a monarch butterfly, indicating its unpalatability.

- The striking colors of a coral snake.

- Behavioral Defenses:

- Flight/Escape: The primary defense for many animals, like a gazelle outrunning a cheetah.

- Alarm Calls: Meerkats issuing warnings to their colony.

- Group Defense: Musk oxen forming a defensive circle around their young.

- Playing Dead (Thanatosis): An opossum feigning death to deter a predator.

Predator Adaptations: The Pursuit of the Meal

In response to prey defenses, predators have evolved their own sophisticated adaptations to locate, capture, and consume their prey.

- Enhanced Senses:

- Vision: The keen eyesight of an eagle or owl.

- Hearing: The acute hearing of a fox to detect prey underground.

- Smell: The powerful olfactory sense of a bear or shark.

- Echolocation: Bats using sound waves to navigate and hunt in darkness.

- Electroreception: Sharks detecting electrical fields generated by prey.

- Physical Adaptations:

- Speed and Agility: The incredible acceleration of a cheetah.

- Stealth: The silent approach of a leopard.

- Weapons: Sharp claws, talons, fangs, venom, or powerful jaws.

- Camouflage: A snow leopard blending into rocky terrain.

- Hunting Strategies:

- Ambush Hunting: A crocodile waiting patiently for prey.

- Pursuit Hunting: A pack of wolves chasing down a caribou.

- Tool Use: Sea otters using rocks to crack open shellfish.

- Cooperative Hunting: Lions working together to bring down large prey.

- Lures/Traps: Anglerfish using a bioluminescent lure to attract prey.

The Ripple Effect: Predation’s Role in Ecosystems

Predation is far more than just a means of survival for individual organisms; it is a fundamental ecological process with profound impacts on the structure and function of entire ecosystems.

- Population Control: Predators help regulate prey populations, preventing overgrazing or overpopulation that could deplete resources and harm the ecosystem. Without predators, prey populations can explode, leading to widespread habitat degradation.

- Natural Selection and Fitness: Predation acts as a powerful selective pressure, favoring individuals with adaptations that enhance their survival. This constant weeding out of less fit individuals strengthens both predator and prey gene pools, driving evolutionary change.

- Community Structure (Trophic Cascades): The presence or absence of top predators can have cascading effects throughout an entire food web. For example, the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park led to a decrease in elk populations, which in turn allowed riparian vegetation to recover, benefiting beaver populations and altering river morphology.

- Biodiversity Maintenance: By preventing a single prey species from dominating, predators can increase species diversity. This is known as a “keystone predator” effect, where a predator’s impact on its community is disproportionately large relative to its abundance.

- Energy Flow: Predation is a primary mechanism for the transfer of energy through trophic levels, from producers to primary consumers, and then to secondary and tertiary consumers. This flow of energy underpins the productivity and complexity of all ecosystems.

Advanced Concepts: The Dynamics of Predator-Prey Interactions

For a deeper understanding, ecologists study the intricate dynamics that govern predator-prey relationships, often revealing complex patterns and cycles.

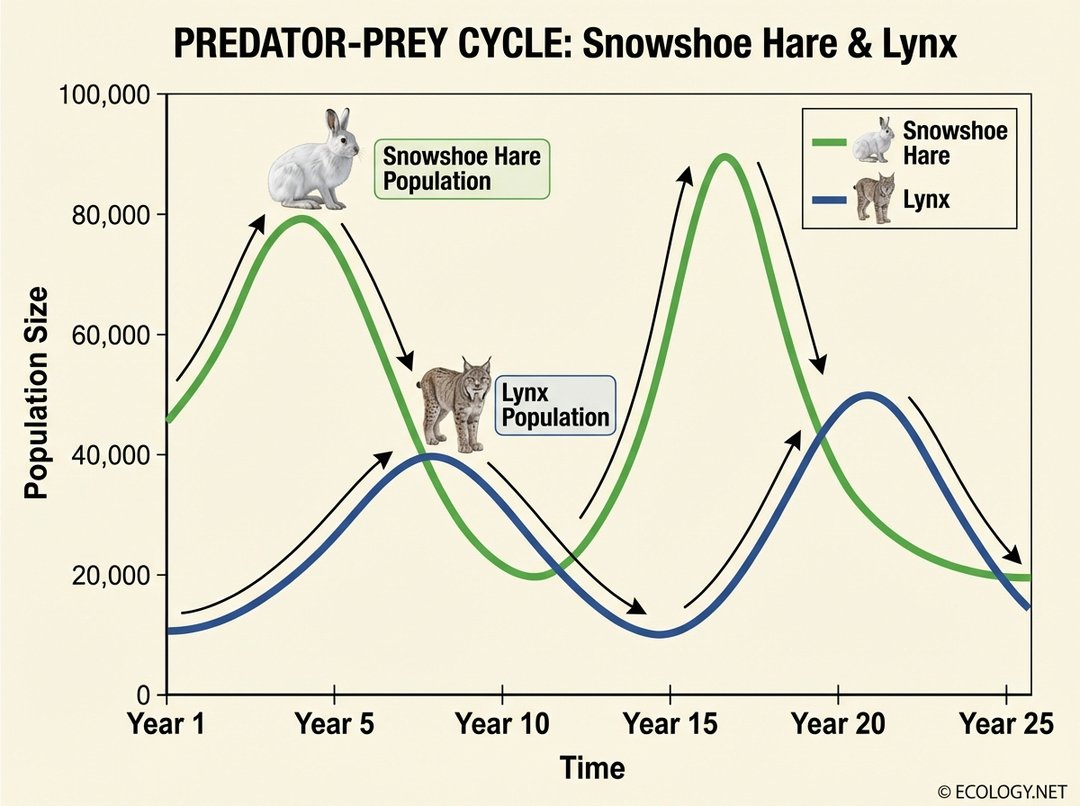

Predator-Prey Cycles

One of the most classic examples of predator-prey dynamics is the cyclical fluctuation of their populations. As prey populations increase, there is more food for predators, leading to an increase in predator numbers. This increased predation then causes the prey population to decline, which in turn leads to a decrease in predator numbers due to food scarcity. This pattern repeats, creating a characteristic oscillating cycle.

A well-known example is the relationship between the snowshoe hare and the Canada lynx in the boreal forests of North America. Historical fur trapping records show distinct, delayed cycles in their populations, with lynx numbers peaking shortly after hare numbers. While simplified models like the Lotka-Volterra equations can illustrate this, real-world cycles are often influenced by additional factors such as food availability for the prey, disease, and alternative prey sources for the predator.

Functional Responses

Ecologists also categorize how a predator’s consumption rate changes with prey density, known as functional responses:

- Type I Functional Response: The number of prey consumed increases linearly with prey density until a saturation point is reached. This is rare in nature, often seen in filter feeders.

- Type II Functional Response: The number of prey consumed increases rapidly at low prey densities but then levels off as prey density increases. This is because the predator becomes satiated or is limited by handling time (the time it takes to capture, subdue, and eat prey). This is the most common type.

- Type III Functional Response: The number of prey consumed increases slowly at low prey densities, then rapidly, and finally levels off at high densities. This S-shaped curve often occurs when predators learn to hunt a specific prey, switch to a more abundant prey, or when there are refuges for prey at low densities.

Numerical Responses

Beyond individual consumption, predator populations can also respond to changes in prey density through a numerical response, meaning an increase in predator numbers due to increased reproduction or immigration when prey are abundant. This contributes significantly to the cyclical patterns observed in many predator-prey systems.

Predation in a Changing World

Human activities are increasingly impacting predator-prey dynamics. Habitat loss, fragmentation, pollution, and climate change can disrupt these delicate balances, leading to declines in both predator and prey populations. Overhunting of predators can lead to prey explosions and ecological damage, while the introduction of invasive predators can decimate native prey species. Conservation efforts often focus on maintaining healthy predator populations as a crucial component of ecosystem integrity. Understanding the complexities of predation is therefore not just an academic exercise, but a vital tool for effective conservation and management in a rapidly changing world.

The Enduring Legacy of Predation

Predation is an inescapable and essential force in the natural world. From the microscopic battle between bacteria and phages to the epic hunt of a killer whale, these interactions drive evolution, regulate populations, and sculpt the very fabric of life on Earth. It is a testament to the intricate beauty and brutal efficiency of nature, a constant reminder that every living thing is part of an interconnected web, where survival often depends on the success or failure of the hunt. By appreciating the multifaceted nature of predation, we gain a deeper respect for the delicate balance that sustains our planet’s incredible biodiversity.