Unlocking the Potential of Permaculture: A Blueprint for Sustainable Living

In an era increasingly defined by ecological challenges, a powerful design philosophy known as Permaculture offers a beacon of hope and a practical pathway toward a more sustainable future. Far more than just a gardening technique, Permaculture is a holistic system for designing human settlements and agricultural systems that mimic the resilience, diversity, and stability of natural ecosystems. It is a thoughtful approach to living that seeks to integrate land, resources, people, and the environment in a mutually beneficial way, creating self-sustaining systems that provide for human needs while enhancing the health of the planet.

At its heart, Permaculture is about working with nature, not against it. It encourages careful observation, thoughtful design, and a deep understanding of ecological principles to create productive landscapes that require minimal external inputs and regenerate over time. Imagine a garden that largely takes care of itself, a farm that builds soil fertility rather than depleting it, or a community that thrives on local resources and strong social connections. This is the promise of Permaculture.

The Foundational Ethics: Guiding Principles for a Better World

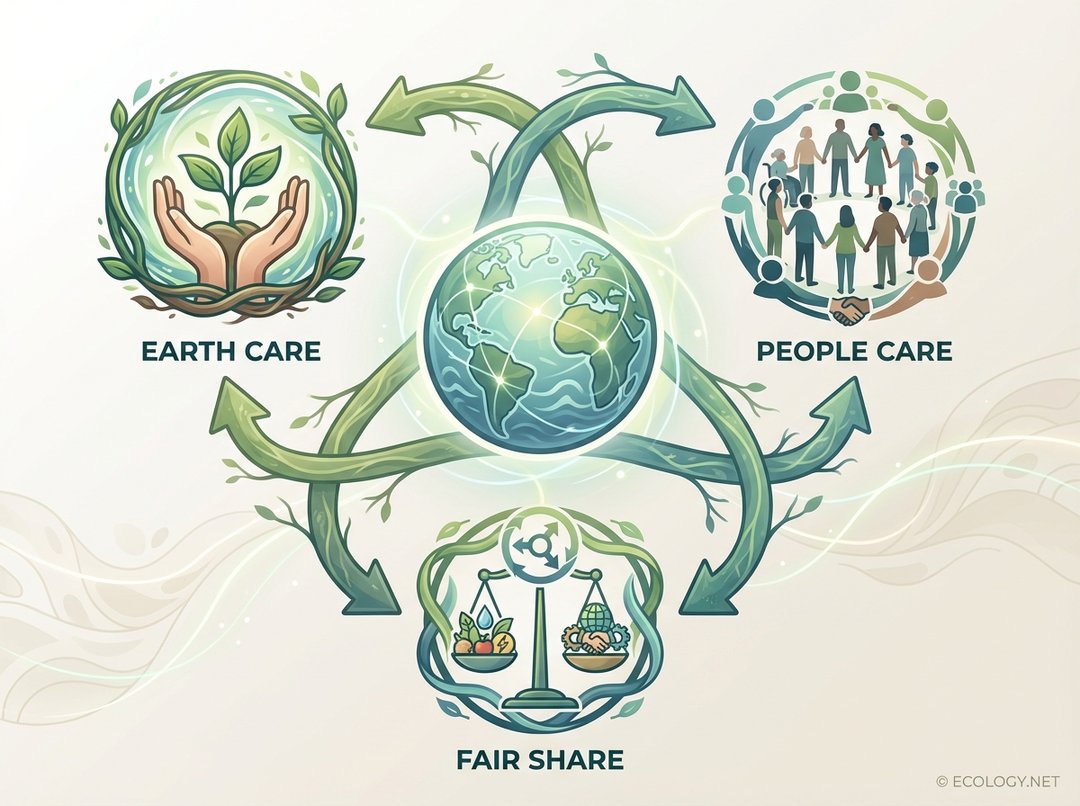

Every permaculture design begins with a set of core ethical principles that serve as its moral compass. These ethics are not merely suggestions but fundamental tenets that guide every decision and action, ensuring that designs are not only productive but also responsible and equitable.

This image visually represents the foundational ethical framework discussed in “The Three Ethical Pillars” section, making the abstract concepts tangible and easy to remember.

The three ethical pillars are:

- Earth Care: This principle emphasizes the responsibility to protect and regenerate natural systems. It means recognizing the intrinsic value of all living things and non-living elements of the Earth. Practically, this translates into actions like building healthy soil, conserving water, protecting biodiversity, and minimizing pollution. It is about understanding that a healthy planet is the foundation for all life.

- People Care: Permaculture acknowledges that human well-being is inextricably linked to ecological health. This ethic focuses on promoting self-reliance, community support, and access to resources for all people. It encourages designing systems that meet human needs for food, shelter, education, and meaningful employment, fostering cooperation and compassion within communities.

- Fair Share (Return of Surplus): This principle addresses the equitable distribution of resources and the responsible use of surplus. It encourages limiting consumption, sharing abundance, and reinvesting any surplus back into the system to support Earth Care and People Care. It challenges the notion of endless growth and promotes a culture of generosity and ecological responsibility.

These ethics are interconnected and interdependent. One cannot truly care for people without caring for the Earth, and a healthy Earth cannot sustain people if resources are not shared fairly.

Key Design Principles: Nature’s Blueprint for Resilience

Beyond the ethics, Permaculture employs a set of design principles derived from observing natural ecosystems. These principles offer practical guidance for creating efficient and resilient systems. Some of the most prominent include:

- Observe and Interact: Before making any changes, spend time observing the site. Understand its climate, soil, water flow, existing vegetation, and human patterns. This deep observation informs intelligent design.

- Catch and Store Energy: Design systems to capture and store energy in various forms, such as water in ponds, solar energy in buildings, or biomass in compost. For example, rainwater harvesting systems collect precious water for later use.

- Obtain a Yield: All designs should aim to produce useful outputs, whether it is food, fiber, energy, or social benefits. The goal is to create productive systems that sustain themselves and their inhabitants.

- Apply Self-Regulation and Accept Feedback: Continuously monitor the system’s performance and be prepared to adjust designs based on feedback. If a plant isn’t thriving, understand why and make changes.

- Use and Value Renewable Resources and Services: Prioritize resources that regenerate naturally, such as solar energy, wind, and biological resources. Utilize natural processes like composting for soil fertility.

- Produce No Waste: Design systems where outputs from one element become inputs for another, mimicking natural cycles. For instance, kitchen scraps become compost, which feeds the garden.

- Design from Patterns to Details: Start with the big picture, understanding the overall patterns of the landscape, then move to the specific details of individual elements.

- Integrate Rather Than Segregate: Place elements together that support each other. Chickens can fertilize fruit trees, and shade-loving plants can grow beneath taller ones.

- Use Small and Slow Solutions: Favor small-scale, locally appropriate interventions over large, industrial ones. Gradual changes are often more sustainable and resilient.

- Use and Value Diversity: Monocultures are vulnerable. Diverse systems are more resilient to pests, diseases, and climate fluctuations. Plant a variety of species.

- Use Edges and Value the Marginal: The interface between two different ecosystems (an “edge”) is often the most productive and diverse. Think of the rich life found at the edge of a forest and a field.

- Creatively Use and Respond to Change: Anticipate and adapt to change, whether it is seasonal variations, climate shifts, or evolving needs. Permaculture is not static.

Practical Applications: Designing with Nature

Permaculture principles manifest in a wide array of practical techniques and design elements. Understanding these applications helps to demystify the concept and illustrate its tangible benefits.

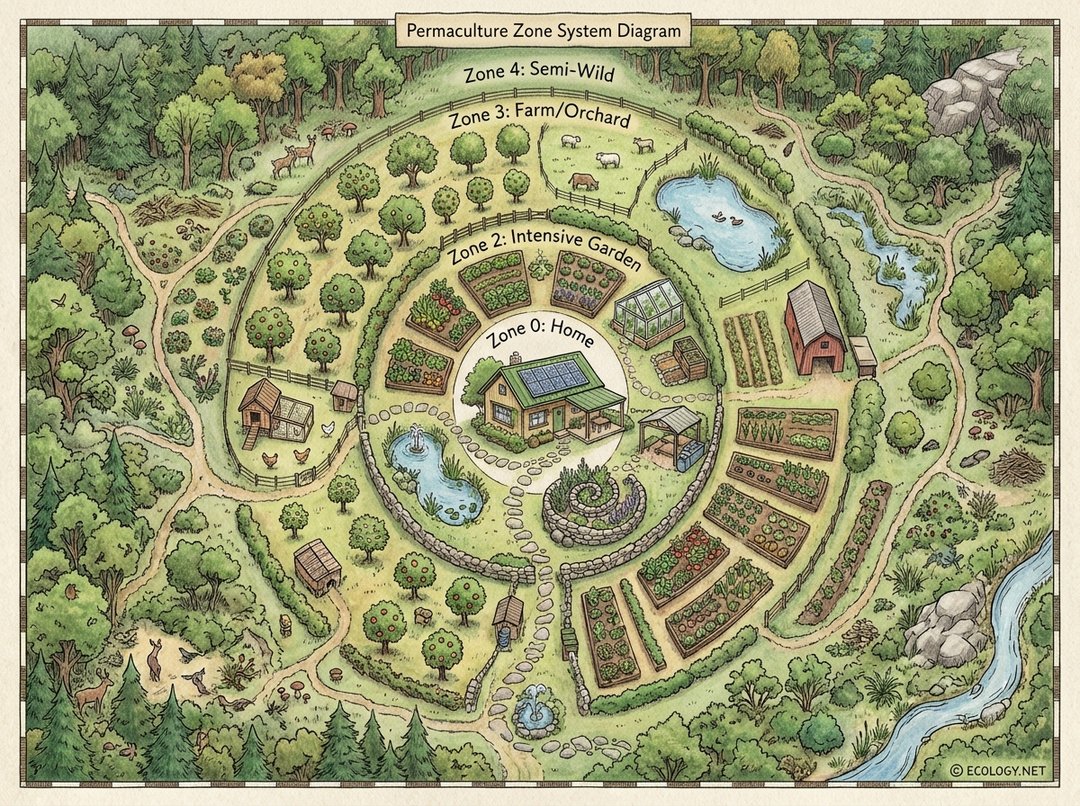

Zone Planning: Organizing for Efficiency

One of the most fundamental permaculture design tools is the concept of “zone planning.” This system organizes elements on a site based on how frequently they need human attention and how often humans interact with them. The goal is to place the most frequently visited and intensively managed elements closest to the home, reducing effort and maximizing efficiency.

This diagram illustrates the “Zone Planning” concept, a key design element in permaculture, helping readers understand how different elements are organized based on frequency of use and human interaction.

Let us explore the typical zones:

- Zone 0: The Home or Core Hub

- This is the center of activity, where people live and spend most of their time.

- It is not typically a productive zone in itself but influences all others.

- Examples: Living spaces, kitchen, office.

- Zone 1: The Intensive Garden

- Located immediately around the home, this zone contains elements that require daily attention.

- Examples: Herb spirals, salad greens, frequently harvested vegetables, propagation areas, worm farms.

- Zone 2: The Main Garden

- A bit further out, this zone hosts elements needing regular but not daily visits.

- Examples: Larger vegetable beds, small fruit trees, berry bushes, chicken coops, compost systems.

- Zone 3: The Farm or Orchard

- This zone is for less frequently managed crops and animals, often requiring weekly or seasonal attention.

- Examples: Orchards, larger field crops, grazing animals, staple crops like potatoes or corn.

- Zone 4: The Semi-Wild or Managed Forest

- This area is largely self-maintaining, with occasional visits for harvesting wild foods, timber, or fodder.

- Examples: Managed woodland, foraging areas, nitrogen-fixing trees, larger animal pastures.

- Zone 5: The Wilderness

- The outermost zone is left untouched and unmanaged, serving as a natural reserve.

- It provides habitat for wildlife, acts as a seed bank, and offers a place for observation and learning from nature.

- Examples: Untouched forest, wetlands, native grasslands.

By thoughtfully arranging these zones, designers can minimize travel time, optimize resource use, and create a more harmonious and productive landscape.

Food Forests: Mimicking Nature’s Abundance

One of the most inspiring and productive permaculture techniques is the creation of a “food forest,” also known as a forest garden. This involves designing a multi-layered planting system that mimics the structure and function of a natural forest, but with a focus on producing food, fiber, and medicine for humans.

This image provides a concrete visual example of “Food Forests,” one of the key design elements and techniques discussed, demonstrating how permaculture principles like diversity and integration are applied in practice.

A typical food forest incorporates seven layers of vegetation:

- Canopy Layer: Tallest fruit and nut trees (e.g., apple, pecan, oak).

- Understory Layer: Smaller fruit trees and large shrubs that tolerate partial shade (e.g., cherry, hazelnut).

- Shrub Layer: Berry bushes and other medium-sized shrubs (e.g., currants, blueberries, elderberry).

- Herbaceous Layer: Non-woody plants like perennial vegetables, herbs, and dynamic accumulators (e.g., rhubarb, comfrey, mint).

- Groundcover Layer: Spreading plants that protect the soil and suppress weeds (e.g., strawberries, clover).

- Rhizosphere (Root) Layer: Root crops like potatoes, carrots, and other tubers.

- Vertical Layer: Climbing plants like grapes, kiwis, or pole beans that utilize vertical space.

Food forests are incredibly resilient, biodiverse, and productive. Once established, they require minimal maintenance, build soil fertility, conserve water, and provide a continuous harvest of diverse foods throughout the year. They are living examples of how humans can integrate seamlessly with natural systems to create abundance.

Other Essential Permaculture Techniques

- Water Harvesting: Techniques like swales (ditches on contour), rain gardens, and keyline design are used to slow, spread, and sink water into the landscape, preventing erosion and recharging groundwater.

- Composting and Vermiculture: Turning organic waste into nutrient-rich soil amendments is central to building healthy soil and closing nutrient loops.

- Companion Planting and Guilds: Strategically planting different species together that benefit each other (e.g., the “three sisters” of corn, beans, and squash) or forming plant “guilds” around a central tree.

- Mulching: Covering soil with organic material to conserve moisture, suppress weeds, regulate soil temperature, and build soil organic matter.

- Integrated Pest Management: Relying on natural predators, beneficial insects, and healthy plant systems rather than chemical pesticides.

The Profound Benefits of Embracing Permaculture

Adopting permaculture principles offers a multitude of benefits, extending far beyond the garden gate:

- Environmental Regeneration: Permaculture actively restores degraded landscapes, builds healthy soil, conserves water, enhances biodiversity, and sequesters carbon, contributing significantly to climate change mitigation.

- Increased Food Security and Self-Reliance: By growing diverse, resilient food systems locally, communities become less dependent on industrial agriculture and vulnerable supply chains.

- Reduced Resource Consumption: Designs minimize the need for external inputs like fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation, leading to lower energy and resource footprints.

- Economic Resilience: Local food production creates local economies, reduces food costs, and can generate income through surplus sales.

- Enhanced Community and Well-being: Working together on permaculture projects fosters community bonds, provides opportunities for learning, and connects people with nature, improving mental and physical health.

- Educational Value: Permaculture provides a living classroom, teaching ecological literacy, practical skills, and systems thinking to all ages.

Embarking on Your Permaculture Journey

For those inspired to explore Permaculture, the journey can begin anywhere, regardless of space or experience.

- Start Small and Observe: Begin with a small project, perhaps a herb spiral or a rain barrel. Spend time observing your chosen area to understand its unique characteristics.

- Educate Yourself: Read books, attend workshops, watch documentaries, and connect with local permaculture practitioners.

- Focus on Soil Health: Healthy soil is the foundation of any productive system. Start composting, mulching, and avoiding chemical inputs.

- Conserve Water: Implement simple water-saving strategies like rainwater harvesting or using greywater for irrigation.

- Plant Perennials: Incorporate perennial plants that provide continuous yields without annual replanting, such as fruit trees, berry bushes, and perennial herbs.

- Connect with Community: Join local gardening groups, permaculture meetups, or community gardens to share knowledge and resources.

Conclusion: A Path Towards a Regenerative Future

Permaculture is more than a set of techniques; it is a philosophy of life that empowers individuals and communities to design their own regenerative futures. By thoughtfully applying its ethics and principles, we can move beyond simply sustaining our current way of life to actively regenerating our planet and our societies. It offers a powerful antidote to the challenges of our time, demonstrating that by working with nature, rather than against it, we can cultivate abundance, resilience, and a truly sustainable existence for all. The journey into Permaculture is a journey into hope, innovation, and a deeper connection with the living world.