Beneath our feet, hidden from plain sight, lies a bustling metropolis of life, a complex web of interactions that sustains nearly all plant life on Earth. This unseen world is orchestrated, in large part, by an extraordinary partnership between plants and fungi, a symbiotic relationship known as mycorrhizae. Far from being mere passive residents, these fungal allies are the unsung heroes of ecosystems, extending the reach of plants and weaving together the very fabric of the natural world.

What are Mycorrhizae? The Unseen Alliance

At its core, mycorrhizae describe a mutualistic association between a fungus and the roots of a plant. The term itself, derived from Greek, literally means “fungus root,” perfectly encapsulating this intimate connection. This isn’t just a casual acquaintance; it’s a deep, evolutionary bond that has shaped terrestrial ecosystems for hundreds of millions of years.

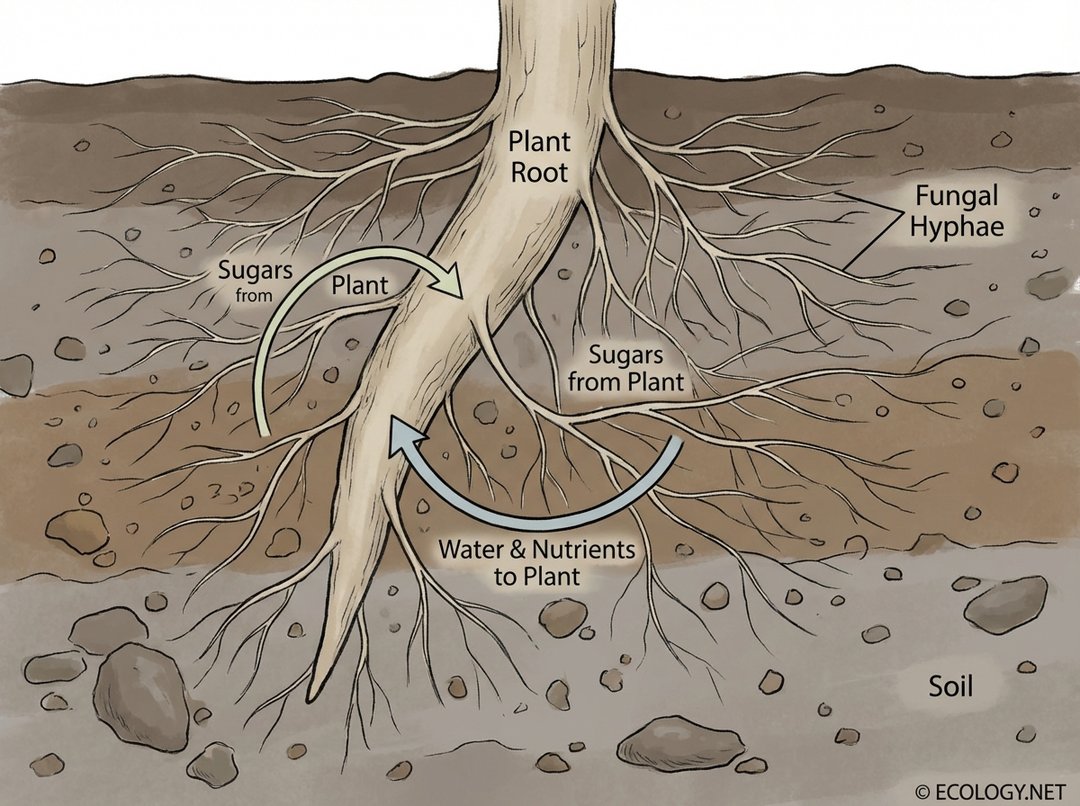

The exchange is elegantly simple yet profoundly impactful:

- For the Plant: The fungus acts as a vastly extended root system. Fungal hyphae, which are microscopic thread-like structures, are far finer and more extensive than plant roots. They can penetrate tiny soil pores inaccessible to roots and efficiently scavenge for essential nutrients like phosphorus, nitrogen, and various micronutrients, as well as water, from a much larger volume of soil. This enhanced uptake is critical for plant growth and survival, especially in nutrient-poor or dry environments.

- For the Fungus: In return for its tireless foraging, the plant provides the fungus with carbohydrates, primarily sugars, produced through photosynthesis. Fungi, lacking chlorophyll, cannot produce their own food, making this sugar supply from the plant an indispensable energy source for their growth and metabolic activities.

This reciprocal exchange is a cornerstone of ecological efficiency, allowing both partners to thrive in conditions where they might struggle alone.

Two Main Types of Mycorrhizae: A Closer Look

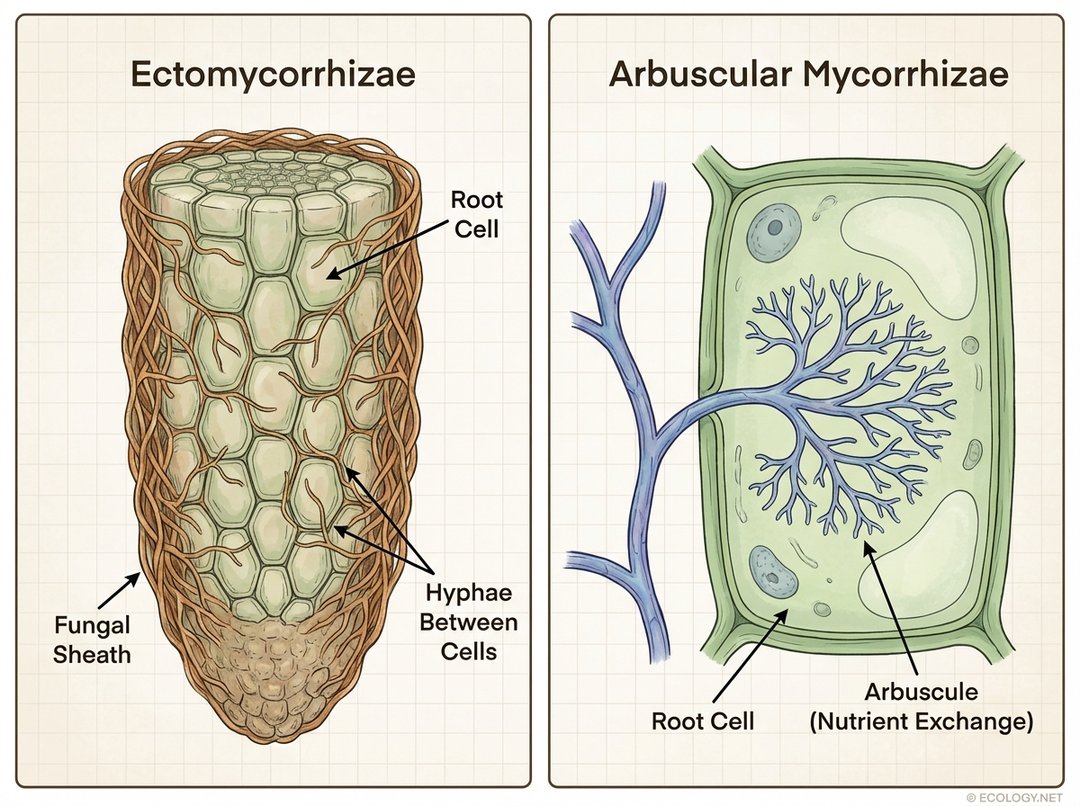

While the fundamental principle of mutual exchange remains consistent, mycorrhizal associations manifest in diverse forms. Scientists generally categorize them into two major types based on how the fungi interact with the plant root cells: Ectomycorrhizae and Arbuscular Mycorrhizae.

Ectomycorrhizae (ECM)

Ectomycorrhizae are predominantly found in association with woody plants, particularly trees in temperate and boreal forests, such as oaks, pines, birches, and firs. Their interaction with the root is primarily external and intercellular:

- Fungal Sheath: The fungus forms a dense, visible mantle or sheath around the outside of the root tip. This protective layer can be quite thick and is often what gives some tree roots their characteristic appearance.

- Hartig Net: From this sheath, fungal hyphae penetrate between the cells of the root cortex, forming an intricate network known as the Hartig net. However, they do not typically enter the plant cells themselves.

- Nutrient Exchange: The primary sites for nutrient and sugar exchange occur across the cell walls within the Hartig net. Ectomycorrhizal fungi are particularly adept at accessing organic forms of nitrogen and phosphorus, often breaking down complex organic matter in the soil.

- Examples: Many edible mushrooms, like boletes and truffles, are the fruiting bodies of ectomycorrhizal fungi, showcasing their vital role in forest ecosystems.

Arbuscular Mycorrhizae (AM)

Arbuscular Mycorrhizae are the most widespread type, forming associations with approximately 80% of all plant species, including most agricultural crops, grasses, shrubs, and many tropical trees. Their interaction is more intimate, involving penetration into the plant cells:

- Intracellular Penetration: Unlike ectomycorrhizae, AM fungi do not form a dense external sheath. Instead, their hyphae grow into the root cortex and then penetrate the cell walls of individual root cells.

- Arbuscules: Once inside the plant cell, the fungal hyphae branch extensively to form highly specialized, tree-like structures called arbuscules. These delicate, finely branched structures dramatically increase the surface area for efficient nutrient and sugar exchange between the fungus and the plant cell.

- Nutrient Exchange: AM fungi are particularly effective at enhancing the plant’s uptake of phosphorus, a crucial but often immobile nutrient in the soil, as well as water and other micronutrients.

- Examples: Common crops like corn, wheat, soybeans, and most vegetables rely heavily on arbuscular mycorrhizal associations for optimal growth.

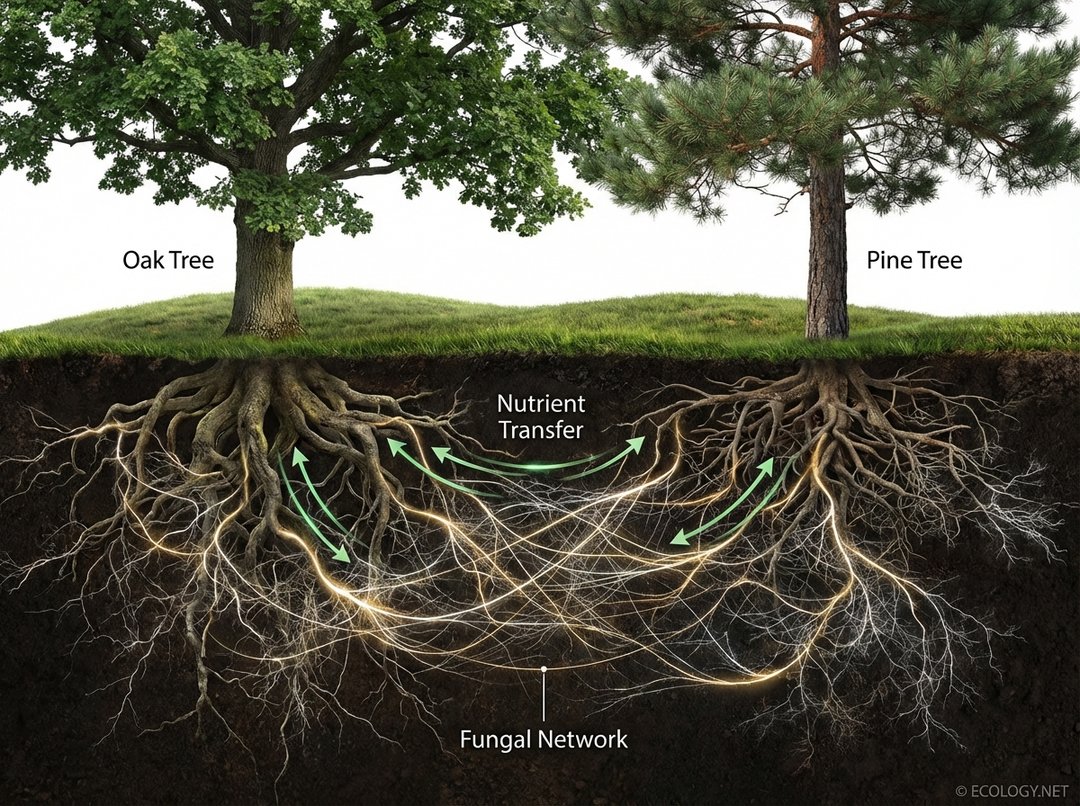

The “Wood Wide Web”: Forest Communication Networks

The concept of mycorrhizae takes on an even more fascinating dimension when considering Common Mycorrhizal Networks (CMNs). Often dubbed the “Wood Wide Web,” these intricate underground fungal networks connect the roots of multiple plants, sometimes even different species, creating a vast biological communication and resource-sharing system.

Imagine a forest floor where individual trees are not isolated entities but rather nodes in a sprawling, subterranean internet. Through the fungal hyphae, resources can be transferred:

- Nutrient Transfer: Sugars from a photosynthetically active “donor” tree can be shared with a shaded seedling struggling to produce its own food. Conversely, water and mineral nutrients acquired by the fungal network from one area can be directed to another plant in need.

- Communication Signals: Beyond mere resource transfer, evidence suggests that plants can use these networks to send chemical warning signals to their neighbors about pest attacks or disease outbreaks, potentially priming them for defense.

- Ecosystem Resilience: This interconnectedness fosters greater ecosystem resilience. It can aid in the survival of young seedlings by connecting them to established “mother trees,” facilitate the establishment of new plant communities, and contribute to the overall health and stability of forests.

The “Wood Wide Web” highlights the profound influence of mycorrhizal fungi in shaping community dynamics and resource allocation within ecosystems, revealing a level of cooperation and interdependence that often goes unnoticed.

Beyond the Basics: Mycorrhizae in Action

The ecological and practical implications of mycorrhizal associations extend far beyond individual plant health, influencing entire ecosystems and offering solutions for sustainable practices.

Ecological Roles

- Soil Structure Improvement: Fungal hyphae bind soil particles together, creating stable aggregates. This improves soil aeration, water infiltration, and reduces erosion, contributing to overall soil health.

- Drought Resistance: By extending the plant’s access to water and improving soil water retention, mycorrhizae significantly enhance a plant’s ability to withstand periods of drought.

- Disease Suppression: Mycorrhizal fungi can act as a protective barrier, physically shielding roots from pathogens and inducing systemic resistance in plants, making them less susceptible to disease.

- Heavy Metal Tolerance: Some mycorrhizal fungi can help plants tolerate toxic levels of heavy metals in contaminated soils by sequestering or detoxifying these elements, offering potential for phytoremediation.

- Biodiversity Enhancement: The presence and diversity of mycorrhizal fungi can influence plant community structure, promoting biodiversity by allowing a wider range of plant species to thrive in various conditions.

Agricultural Applications

Understanding and harnessing mycorrhizal power holds immense promise for sustainable agriculture:

- Reduced Fertilizer Use: By enhancing nutrient uptake, mycorrhizal inoculants can significantly reduce the need for synthetic phosphorus and nitrogen fertilizers, lowering input costs and minimizing environmental pollution.

- Improved Crop Yields: Healthier, more robust root systems lead to stronger plants and higher yields, especially in marginal soils or under stressful conditions.

- Restoration of Degraded Lands: Mycorrhizal fungi are crucial for the successful establishment of plants in disturbed or degraded environments, such as mine tailings or eroded lands, aiding in ecological restoration efforts.

- Sustainable Farming Practices: Integrating mycorrhizal management into farming practices supports a more holistic and environmentally friendly approach to food production, fostering long-term soil fertility and ecosystem health.

Unlocking the Potential: Future Directions

Research into mycorrhizae continues to uncover new layers of complexity and utility. Scientists are exploring:

- The genetic mechanisms that govern these intricate symbioses.

- The specific roles of different fungal species in various plant communities.

- Advanced methods for producing and applying mycorrhizal inoculants to optimize their benefits in agriculture and forestry.

- The potential of mycorrhizae in mitigating climate change through enhanced carbon sequestration in soils.

Conclusion

Mycorrhizae represent one of nature’s most enduring and vital partnerships, a testament to the power of cooperation in the living world. From the microscopic exchange of sugars and nutrients within a single root cell to the vast, interconnected networks that underpin entire forests, these fungal allies are indispensable. They remind us that the health of our planet is often sustained by unseen forces, intricate relationships that deserve our understanding, appreciation, and protection. By recognizing and fostering these hidden alliances, we can cultivate healthier soils, more resilient ecosystems, and a more sustainable future for all life.