The Earth’s Hidden Sponge: Understanding Moisture Retention

Imagine a world where every drop of rain vanished instantly, leaving parched earth and wilting life. This stark image underscores the profound importance of a fundamental ecological process: moisture retention. Far from a mere technical term, moisture retention is the Earth’s ingenious way of holding onto precious water, making it available for ecosystems, agriculture, and ultimately, all life. It is the silent workhorse behind lush forests, bountiful harvests, and the very air we breathe.

What Exactly is Moisture Retention?

At its core, moisture retention refers to the capacity of a natural system, primarily soil and vegetation, to absorb and hold water against the forces of gravity and evaporation. It is not just about how much water a system can hold, but also how long it can hold it, and how accessible that water remains for plants and other organisms. This vital capacity dictates the resilience of landscapes to drought, influences local climates, and underpins the productivity of nearly every terrestrial ecosystem.

The Role of Soil: Earth’s Primary Reservoir

The soil beneath our feet is arguably the most crucial player in the drama of moisture retention. Think of soil as a complex, living sponge, its ability to hold water determined by a fascinating interplay of its physical structure, composition, and biological activity.

Soil Types and Their Thirst

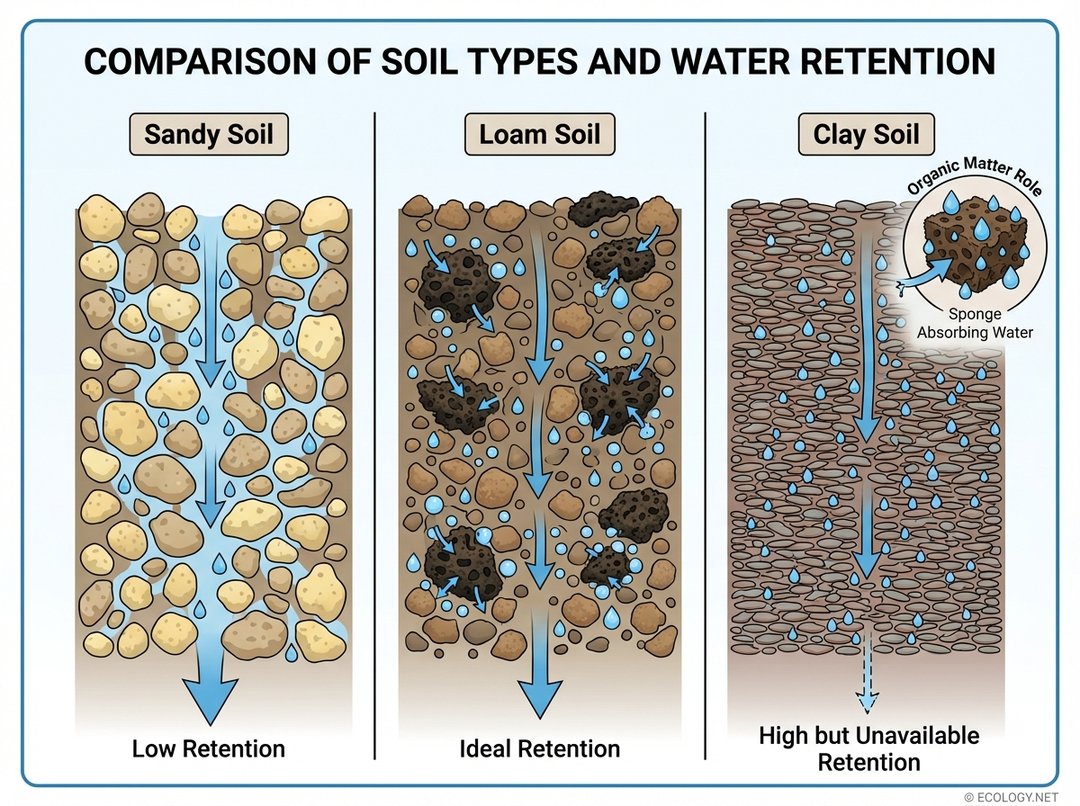

Different soil types possess vastly different water-holding capabilities:

- Sandy Soil: Characterized by large, coarse particles, sandy soil has large pore spaces. Water drains through it very quickly, leading to low moisture retention. While it allows for excellent aeration, its inability to hold water for extended periods can be a challenge for plant growth.

- Clay Soil: Composed of extremely fine, tightly packed particles, clay soil has very small pore spaces. It can hold a significant amount of water due to its large surface area, but much of this water is held so tightly that it becomes unavailable to plant roots. This leads to high, but often inaccessible, retention.

- Loam Soil: Often considered the gardener’s ideal, loam soil is a balanced mix of sand, silt, and clay particles, along with a healthy dose of organic matter. This combination creates a diverse range of pore sizes, allowing for both good drainage and excellent water retention, making water readily available for plants.

The Magic of Organic Matter

Beyond particle size, organic matter is a superstar when it comes to moisture retention. Decomposing plant and animal material acts like countless tiny sponges within the soil, absorbing and holding many times its own weight in water. It also improves soil structure, creating stable aggregates that enhance porosity and allow for better infiltration and storage. A soil rich in organic matter is a resilient soil, capable of buffering against both drought and heavy rainfall.

Vegetation’s Contribution: Living Water Managers

Plants are not just passive beneficiaries of soil moisture; they are active architects of its retention. From the towering trees of a forest to the humble grasses of a meadow, vegetation plays a multifaceted role in keeping landscapes hydrated.

Canopy Interception and Reduced Evaporation

The leaves and branches of plants, particularly in dense forests, intercept rainfall before it even reaches the ground. This canopy interception slows the impact of raindrops, reducing soil erosion, and allows some water to evaporate directly from leaf surfaces. While some water is lost this way, it also moderates the amount of water hitting the ground, allowing for more gradual infiltration. Furthermore, the shade provided by dense canopies reduces direct sunlight on the soil, significantly lowering evaporation rates from the soil surface.

Root Systems: Anchors and Pathways

Plant roots are engineering marvels that enhance moisture retention in several ways:

- Soil Stabilization: Roots bind soil particles together, preventing erosion and maintaining soil structure. This stable structure allows for better water infiltration and reduces runoff.

- Creating Channels: As roots grow and decay, they create a network of channels and pores within the soil. These pathways act like miniature pipelines, allowing water to penetrate deeper into the soil profile, where it can be stored for longer periods.

- Organic Matter Contribution: Roots themselves contribute organic matter to the soil as they shed cells and eventually decompose, further boosting the soil’s water-holding capacity.

Consider the intricate prop roots of a mangrove forest, a prime example of vegetation actively trapping water and organic matter, creating a unique, water-rich environment that supports a diverse array of life.

Topography and Slope: The Lay of the Land

The physical shape of the land, or its topography, exerts a powerful influence on how water moves across and into the landscape, directly affecting moisture retention.

Steep Slopes Versus Gentle Valleys

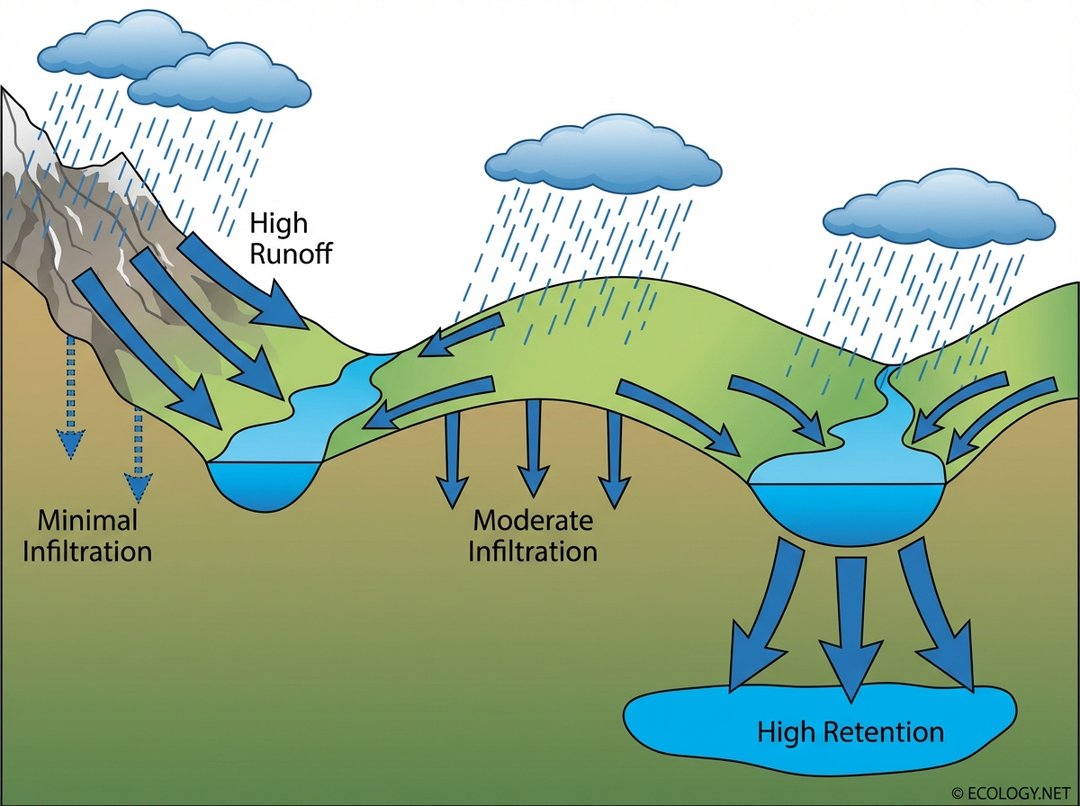

* Steep Slopes: On steep gradients, gravity quickly pulls water downhill. Rainfall often becomes surface runoff, moving rapidly across the land with minimal opportunity to infiltrate the soil. This results in low moisture retention and can contribute to erosion.

* Gentle Slopes: As the slope decreases, water has more time to soak into the ground. Infiltration rates increase, leading to moderate moisture retention.

* Valleys and Depressions: Low-lying areas, valleys, and natural depressions act as collection points for water. Runoff from surrounding higher ground accumulates here, allowing ample time for infiltration and often leading to significant water pooling. These areas typically exhibit the highest moisture retention.

The Microclimate Connection: Local Weather Makers

Moisture retention is not just about water in the soil; it profoundly influences the local atmosphere, creating distinct microclimates. Landscapes with high moisture retention tend to have higher humidity, cooler daytime temperatures, and more frequent dew formation. This localized moisture can even contribute to cloud formation and precipitation patterns, demonstrating a feedback loop between the land and the sky.

Ecological Significance: The Web of Life

The ability of a landscape to retain moisture is a cornerstone of ecological health.

- Plant Growth: Consistent access to water is fundamental for photosynthesis and nutrient uptake, directly impacting plant productivity and survival.

- Biodiversity: Stable water availability supports a wider array of plant species, which in turn provides habitat and food for diverse animal populations.

- Drought Resilience: High moisture retention acts as a buffer during dry spells, allowing ecosystems to withstand periods of water scarcity more effectively.

- Nutrient Cycling: Water is the medium through which nutrients are transported in the soil and absorbed by plants. Adequate moisture retention ensures efficient nutrient cycling.

- Streamflow Regulation: Landscapes that retain moisture release water gradually into streams and rivers, helping to maintain consistent baseflows and reducing the severity of floods.

Human Impact and Management: Stewarding Our Water

Human activities can significantly alter natural moisture retention capabilities.

- Negative Impacts:

- Deforestation: Removing forests reduces canopy interception, increases soil erosion, and diminishes organic matter, leading to decreased retention.

- Urbanization: Paving over natural surfaces with impervious materials like concrete and asphalt prevents water infiltration, leading to increased runoff and reduced groundwater recharge.

- Soil Compaction: Heavy machinery and livestock can compact soil, reducing pore space and hindering water infiltration.

- Intensive Agriculture: Practices that deplete soil organic matter can severely reduce its water-holding capacity.

- Positive Management Strategies:

- Reforestation and Afforestation: Planting trees helps restore natural water cycles and improve soil health.

- Sustainable Agriculture: Practices like cover cropping, no-till farming, and adding compost enhance soil organic matter and structure.

- Terracing and Contour Plowing: On sloped land, these techniques slow down water flow, allowing more time for infiltration.

- Permeable Surfaces: In urban areas, using permeable pavers and green infrastructure allows rainwater to soak into the ground.

- Wetland Restoration: Wetlands are natural sponges, and their restoration significantly boosts regional moisture retention.

Delving Deeper: Advanced Concepts in Moisture Dynamics

For those seeking a more granular understanding, the science of moisture retention extends into specific hydrological and soil physics concepts.

- Field Capacity: This is the maximum amount of water that a soil can hold against the force of gravity after excess water has drained away. It represents the upper limit of plant-available water.

- Permanent Wilting Point: The moisture content at which plants can no longer extract water from the soil and permanently wilt. Water held below this point is unavailable to plants.

- Available Water Capacity: The difference between field capacity and the permanent wilting point, representing the range of water content that is accessible to plants.

- Matric Potential: This refers to the force by which water is held in the soil matrix. As soil dries, the matric potential becomes more negative, indicating water is held more tightly and is harder for plants to extract.

- Hydrological Cycle Integration: Moisture retention is a critical component of the global hydrological cycle, influencing evaporation, transpiration, groundwater recharge, and surface runoff, thereby impacting regional and global water balances.

A Vital Connection to Life

Moisture retention is a silent, yet powerful, force shaping our world. From the microscopic pores in soil to the vast expanse of a mangrove forest, the Earth’s ability to hold onto water is a testament to the intricate balance of natural systems. Understanding and actively promoting healthy moisture retention practices are not just ecological imperatives; they are fundamental to ensuring a sustainable and thriving future for all life on our planet.