Understanding Local Extinction: A Critical Concept in Conservation

When the word “extinction” is uttered, it often conjures images of the last dodo, a species vanishing from the face of the Earth forever. This dramatic and irreversible loss is known as global extinction. However, a more subtle, yet equally significant, phenomenon occurs far more frequently: local extinction. This concept is crucial for understanding the health of our planet’s ecosystems and the ongoing challenges faced by countless species.

Global vs. Local: Drawing the Line

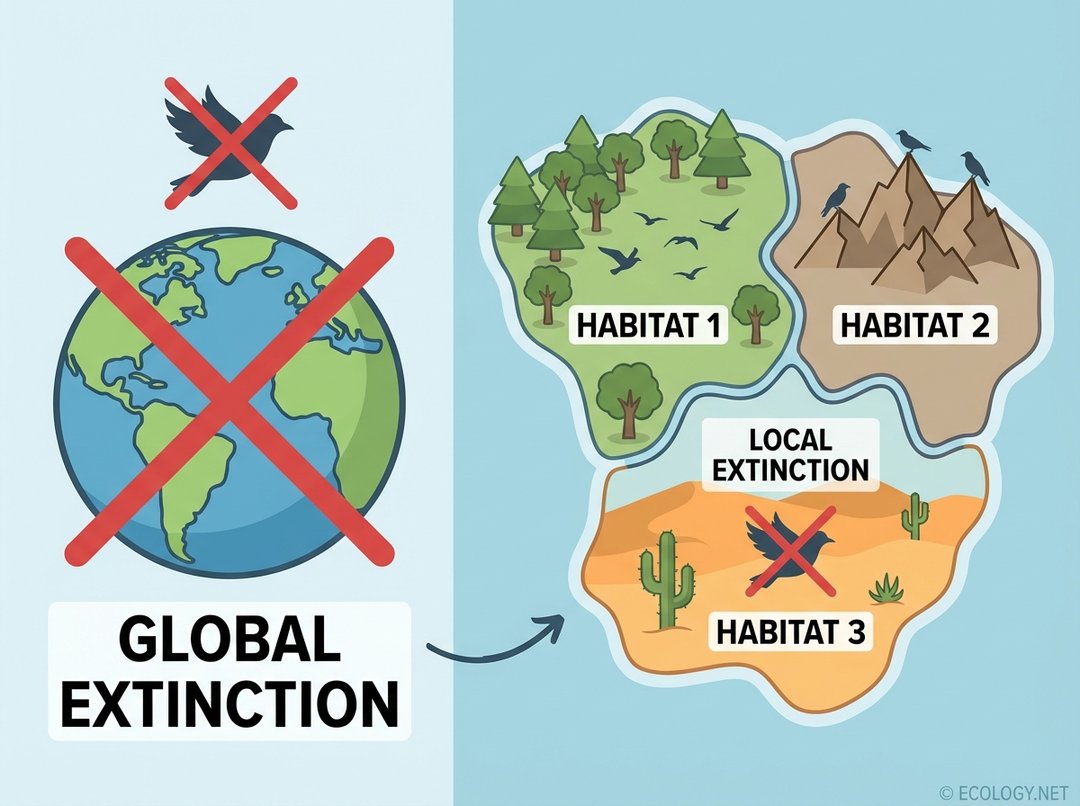

To truly grasp local extinction, it is essential to first distinguish it from its global counterpart. Global extinction signifies the complete disappearance of a species from every corner of the planet. Once a species is globally extinct, it is gone forever, leaving a permanent void in the tapestry of life.

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, describes the disappearance of a species from a specific geographic area, while populations of that same species still exist elsewhere in the world. Imagine a species of frog that once thrived in a particular wetland. If that wetland is drained and the frogs vanish from it, but healthy populations persist in other wetlands hundreds of miles away, that is a local extinction. The species itself is not gone, but its presence in that specific location has been erased.

This distinction is not merely academic. It highlights that even if a species is not teetering on the brink of global disappearance, its local losses can have profound ecological consequences.

The Ripple Effect: Why Local Extinctions Matter

While a local extinction might not signal the end of a species, it can trigger a cascade of negative effects within the affected ecosystem. Every species plays a role, no matter how small, in the intricate web of life. When a species vanishes from a particular area, its role goes unfilled, leading to imbalances.

- Loss of Ecosystem Services: Many species provide vital services, such as pollination, pest control, seed dispersal, or nutrient cycling. The local disappearance of pollinators, for instance, can lead to reduced plant reproduction and crop yields.

- Disruption of Food Webs: Predators lose a food source, prey species might proliferate unchecked, or scavengers might lose an important resource. This can destabilize the entire food chain.

- Reduced Genetic Diversity: Each local population contributes to the overall genetic diversity of a species. Losing a population means losing unique genetic traits that might be crucial for the species’ long-term survival and adaptation to changing environments.

- Increased Vulnerability: A species with fewer local populations is inherently more vulnerable to global extinction. If a widespread disease or a catastrophic event strikes one of the remaining populations, the species’ future becomes far more precarious.

Real-World Examples: Witnessing Local Loss

Local extinctions are not abstract concepts; they are happening all around us, often unnoticed by the general public. Consider the plight of the Rusty Patched Bumble Bee (Bombus affinis) in North America. Once common across much of the eastern and midwestern United States and parts of Canada, its populations have plummeted dramatically in many areas.

In many states where it was once abundant, the Rusty Patched Bumble Bee is now locally extinct. This decline is attributed to a combination of factors, including habitat loss due to agricultural expansion and urbanization, pesticide use, climate change, and disease. While the species still persists in some isolated pockets, its absence from vast portions of its historical range represents a significant ecological loss for those regions, impacting the pollination of wildflowers and crops.

Another classic example is the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) in the contiguous United States. Historically, grizzlies roamed much of the western half of the country. Today, they are locally extinct in many states, confined primarily to a few isolated populations in places like Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. While the species is not globally extinct, its absence from vast stretches of its former habitat has altered ecosystems, affecting everything from berry dispersal to the regulation of elk populations.

The Dynamics of Persistence: Metapopulations

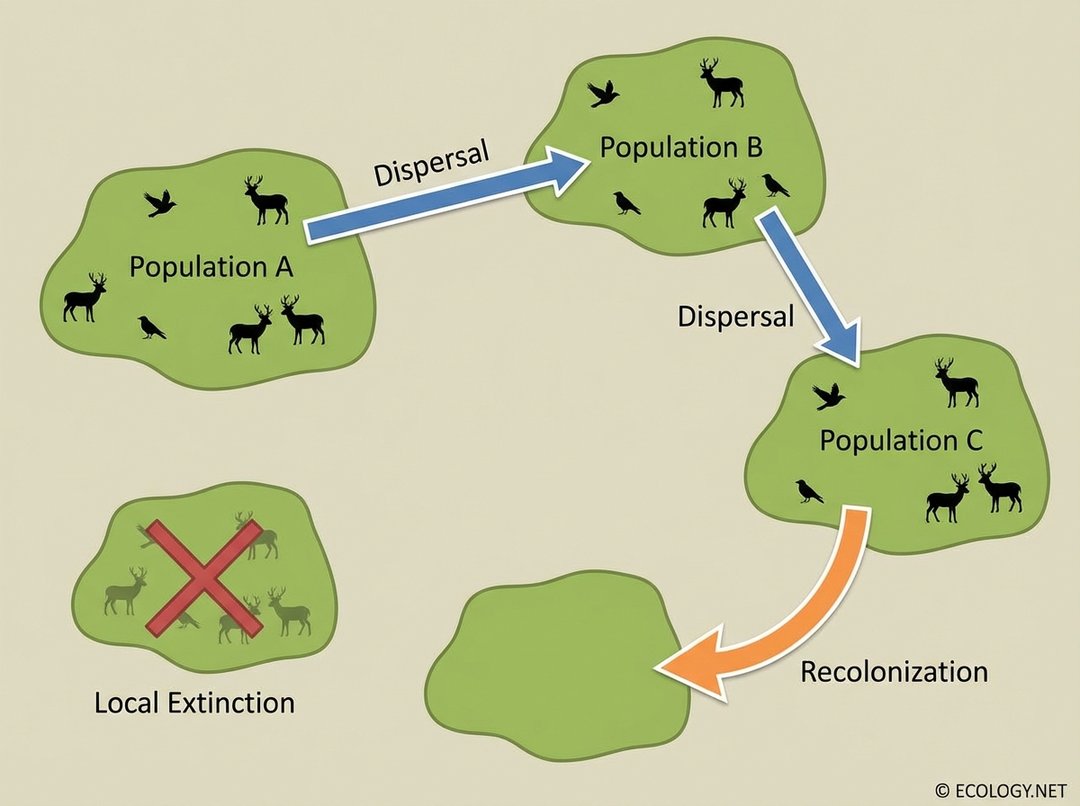

To understand how species can persist despite ongoing local extinctions, ecologists often turn to the concept of metapopulations. A metapopulation is a “population of populations,” consisting of several spatially separated populations of the same species that are connected by occasional dispersal of individuals.

Imagine a landscape dotted with small, isolated patches of suitable habitat, like islands in a sea of unsuitable terrain. Each patch might support a small population of a particular species. Within this system, local extinctions can occur in some patches due to random events, disease, or habitat degradation. However, if other healthy populations exist nearby, individuals from those populations might disperse and recolonize the empty patches, preventing the overall species from disappearing.

This dynamic interplay of local extinctions and recolonizations is a natural process, especially in fragmented landscapes. However, human activities often disrupt this delicate balance. If habitat patches become too isolated, or if the intervening landscape becomes too hostile, dispersal becomes impossible. This prevents recolonization, making local extinctions permanent and increasing the risk of global extinction for the entire species.

Key components of metapopulation dynamics include:

- Patch Extinction: The disappearance of a population from a single habitat patch.

- Recolonization: The re-establishment of a population in an empty patch by individuals dispersing from other patches.

- Dispersal: The movement of individuals between patches, which is crucial for maintaining genetic flow and facilitating recolonization.

Understanding metapopulations is vital for conservation because it highlights that protecting individual populations is not enough. We must also protect the connections between them and ensure the quality of the landscape matrix that separates them.

From Local Loss to Global Threat: The Slippery Slope

While local extinction is not global extinction, it is often a precursor. A species that experiences widespread local extinctions becomes increasingly fragmented, its genetic diversity erodes, and its ability to adapt to new threats diminishes. Each local loss chips away at the species’ overall resilience, pushing it closer to the brink of global disappearance.

Consider the cumulative effect: if a species loses 90% of its historical range through local extinctions, the remaining 10% becomes incredibly vulnerable. A single disease outbreak or a localized environmental disaster could then easily wipe out the last remaining populations, leading to global extinction.

Conservation in Action: Preventing and Reversing Local Extinction

The good news is that local extinctions are often reversible, and proactive conservation efforts can prevent them. Strategies include:

- Habitat Restoration: Rebuilding degraded habitats, such as wetlands, forests, or grasslands, can create new homes for species and allow existing populations to expand.

- Habitat Connectivity: Creating wildlife corridors, underpasses, or overpasses helps connect isolated habitat patches, facilitating dispersal and recolonization.

- Species Reintroduction: In cases where a species has been locally extirpated, individuals from healthy populations elsewhere can be reintroduced to restore its presence in the area. This requires careful planning and suitable habitat.

- Reducing Threats: Addressing the root causes of local extinction, such as pollution, invasive species, and unsustainable resource use, is paramount.

- Protected Areas: Establishing and effectively managing national parks, wildlife refuges, and other protected areas provides safe havens for species.

- Community Engagement: Involving local communities in conservation efforts fosters a sense of stewardship and ensures long-term success.

A Call to Action: Recognizing the Value of Every Place

Local extinction serves as a powerful reminder that conservation is not just about saving the rarest species from global disappearance. It is also about maintaining the richness and integrity of biodiversity in every landscape, from our local parks to vast wilderness areas. Every local population contributes to the health of its ecosystem and the overall resilience of its species.

By understanding the dynamics of local extinction and the critical role of metapopulations, we can develop more effective conservation strategies that protect not just species, but the intricate web of life in all its local manifestations. The future of biodiversity depends on our ability to recognize and value life, not just globally, but in every place it calls home.