Unlocking Nature’s Synergy: A Deep Dive into Intercropping

For centuries, farmers have sought ways to coax more from the land, often leading to practices that, while productive in the short term, can deplete soil and reduce biodiversity. However, a timeless agricultural strategy known as intercropping offers a powerful alternative, harnessing the inherent wisdom of nature to create more resilient, productive, and sustainable farming systems. This practice is not merely about planting different crops together; it is about fostering a cooperative ecosystem where plants mutually benefit, mimicking the diversity found in natural environments.

What Exactly is Intercropping?

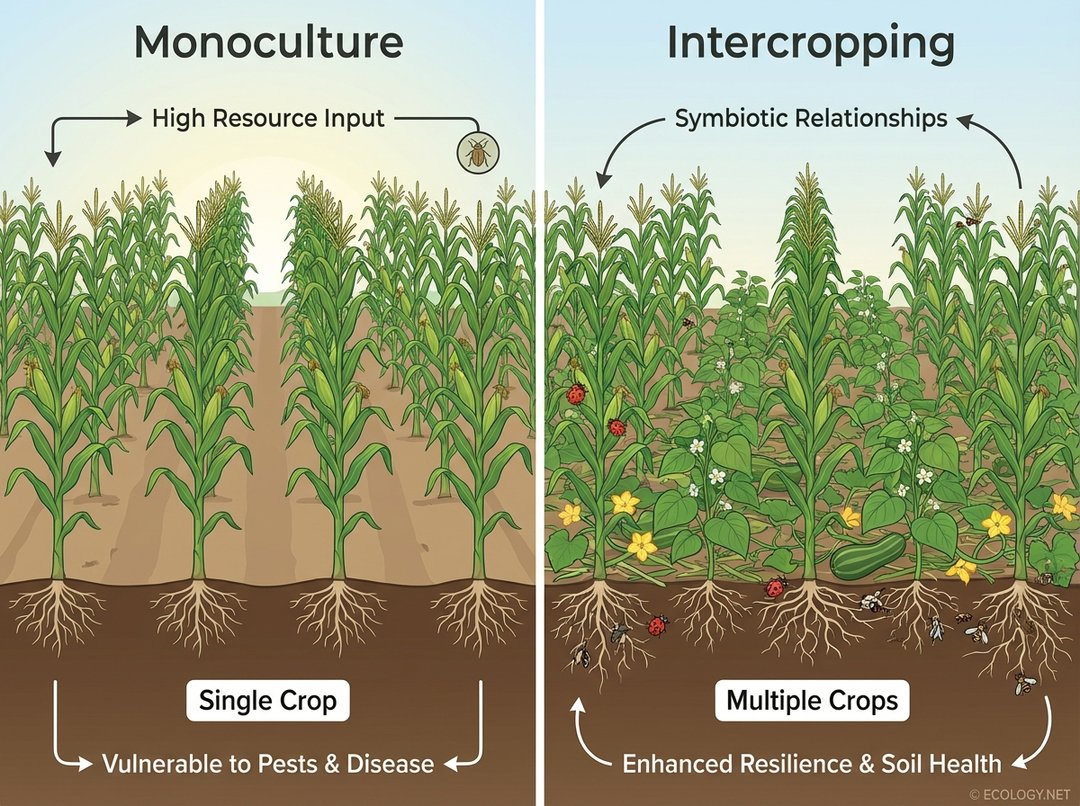

At its heart, intercropping is the practice of growing two or more crops simultaneously in the same field. This stands in stark contrast to monoculture, the dominant agricultural model of cultivating a single crop over a large area. While monoculture prioritizes uniformity and ease of management, intercropping embraces diversity, creating a dynamic interplay between different plant species.

The visual difference is striking. A monoculture field presents a uniform sea of one plant, whereas an intercropped field showcases a vibrant tapestry of different species growing side by side. This fundamental shift from singularity to multiplicity underpins the myriad benefits that intercropping offers.

The Multifaceted Benefits of Intercropping

The advantages of intercropping extend far beyond simply having more plants in a field. This practice cultivates a range of ecological and economic benefits, making it a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture.

- Increased Overall Yield: By utilizing resources more efficiently, intercropped systems often produce a greater total biomass or yield per unit area compared to growing the same crops separately. This is known as the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER).

- Enhanced Pest and Disease Control: Crop diversity can confuse pests, making it harder for them to locate their host plants. Some companion plants can also repel pests or attract beneficial insects that prey on harmful ones.

- Improved Soil Health: Different crops contribute to soil health in various ways. Legumes, for instance, fix atmospheric nitrogen, enriching the soil for neighboring plants. Diverse root systems also improve soil structure and organic matter content.

- Weed Suppression: A dense canopy created by multiple crops can outcompete weeds for sunlight, water, and nutrients, reducing the need for herbicides.

- Resource Efficiency: Plants with different growth habits and nutrient requirements can utilize resources like sunlight, water, and nutrients more effectively from various layers of the soil and canopy.

- Reduced Risk: Relying on multiple crops diversifies a farmer’s income stream and provides a buffer against crop failure due to pests, diseases, or adverse weather conditions affecting a single crop.

- Biodiversity Enhancement: Intercropping supports a wider range of beneficial insects, microorganisms, and wildlife, contributing to overall ecosystem health.

Popular Intercropping Systems and Examples

Intercropping is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Various methods have evolved, each suited to different crops, climates, and agricultural goals.

- Row Intercropping: Involves planting crops in alternating rows. For example, rows of corn alternating with rows of beans.

- Mixed Intercropping: Crops are grown together without distinct row arrangements, often broadcast sown.

- Relay Intercropping: A second crop is planted into a standing crop before the first crop is harvested. For instance, planting clover into a wheat field before the wheat is ready for harvest.

- Strip Intercropping: Growing two or more crops in strips wide enough to allow for independent cultivation but narrow enough for the crops to interact ecologically.

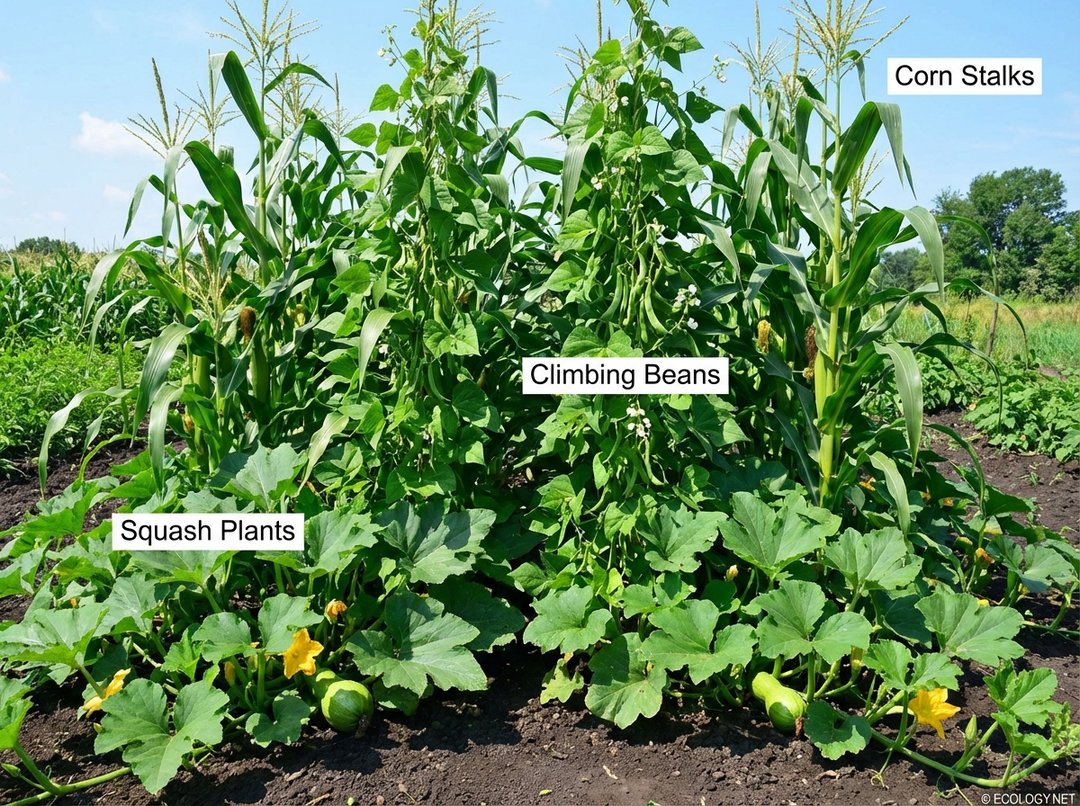

One of the most celebrated and historically significant examples of intercropping is the “Three Sisters” system, practiced for centuries by Indigenous peoples across North America.

This ingenious system combines corn, beans, and squash in a mutually beneficial arrangement:

- Corn provides a tall stalk for the beans to climb, offering vertical support.

- Beans, being legumes, fix nitrogen in the soil, enriching it for the nitrogen-hungry corn and squash.

- Squash plants with their broad leaves spread across the ground, shading the soil to suppress weeds, retain moisture, and deter pests with their prickly stems.

This example beautifully illustrates how different plants can work together, creating a mini-ecosystem that is more productive and resilient than any single crop grown alone. Other common examples include planting cereals with legumes, or brassicas with aromatic herbs for pest deterrence.

The Science Behind the Synergy: Ecological Principles at Play

The success of intercropping is rooted in fundamental ecological principles that promote cooperation over competition. Understanding these mechanisms helps in designing effective intercropping systems.

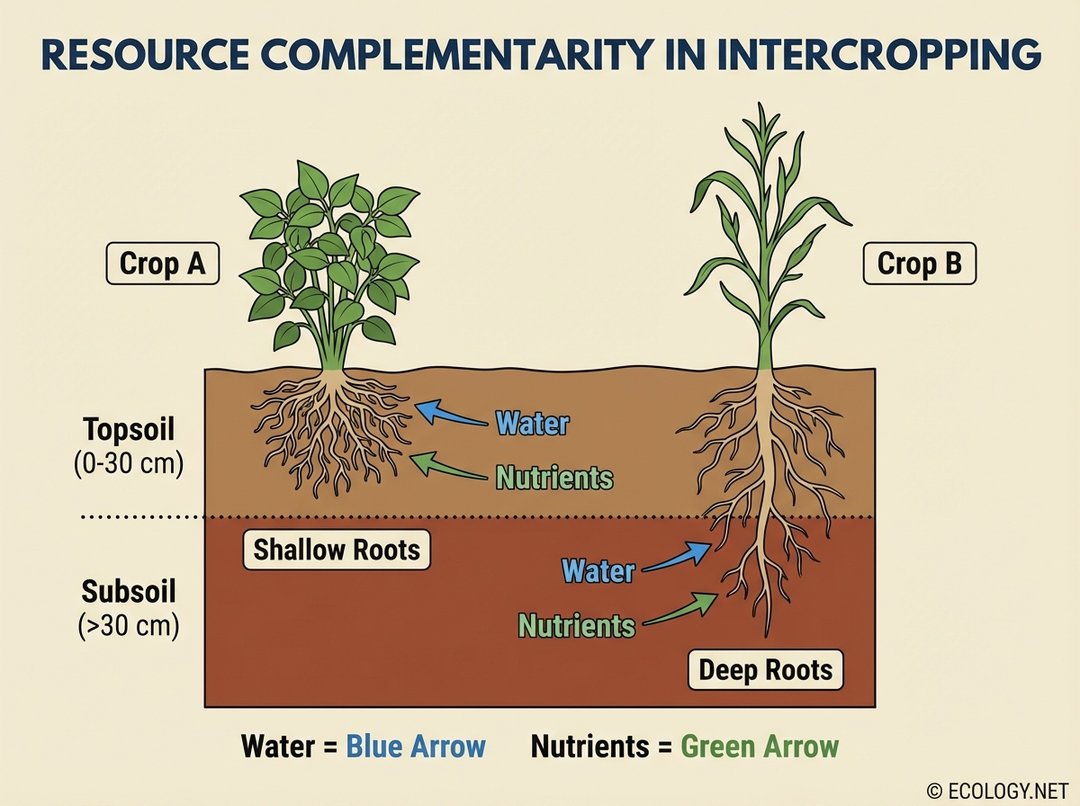

Resource Complementarity

One of the most significant advantages of intercropping stems from resource complementarity. Different plant species often have varying requirements for resources like sunlight, water, and nutrients, as well as different ways of accessing them.

Consider the example of plants with different rooting depths. A crop with shallow roots might efficiently absorb nutrients and water from the topsoil, while a companion crop with deep roots can tap into resources found in lower soil horizons. This spatial partitioning of resources minimizes direct competition and maximizes the overall utilization of available nutrients and water from the entire soil profile. Similarly, plants with different canopy structures can utilize sunlight at different heights, ensuring that light energy is captured more effectively throughout the day.

Facilitation and Mutualism

Beyond simply avoiding competition, intercropping often involves direct facilitative interactions where one plant benefits another. The classic example is the nitrogen-fixing ability of legumes. These plants host bacteria in their root nodules that convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by plants. When legumes are intercropped with non-leguminous plants, they effectively fertilize their neighbors, reducing the need for synthetic nitrogen inputs.

Pest and Disease Management

The “confusion effect” is a key mechanism in pest control. A diverse array of plants can make it harder for pests to locate their specific host crop. Some plants also act as natural repellents, emitting volatile compounds that deter pests. Others serve as “trap crops,” attracting pests away from the main crop, or as “banker plants,” providing habitat and food for beneficial insects that prey on pests. This biological control reduces reliance on chemical pesticides.

Microclimate Modification

Taller crops can provide shade for shorter, more sensitive crops, protecting them from excessive heat or strong winds. This modification of the microclimate can create more favorable growing conditions for certain species, especially in harsh environments.

Challenges and Considerations for Implementation

While the benefits of intercropping are compelling, its implementation is not without challenges. It requires a deeper understanding of plant interactions and more nuanced management compared to monoculture.

- Increased Management Complexity: Planning, planting, and harvesting multiple crops simultaneously can be more complex and labor-intensive.

- Mechanization Difficulties: Standardized farm machinery is often designed for monoculture, making mechanical planting, cultivation, and harvesting in intercropped fields more challenging.

- Crop Selection: Choosing the right combination of crops is crucial. Incompatible species can lead to competition rather than cooperation, reducing yields.

- Nutrient Management: Balancing the nutrient needs of different crops can be intricate, requiring careful soil analysis and fertilization strategies.

Despite these challenges, ongoing research and innovative farming techniques are continuously refining intercropping practices, making them more accessible and efficient for a wider range of agricultural systems.

Intercropping in a Changing World

As the global population grows and the impacts of climate change intensify, the need for resilient and sustainable food systems becomes ever more critical. Intercropping offers a powerful tool in this endeavor. By fostering biodiversity, enhancing soil health, reducing reliance on synthetic inputs, and increasing overall productivity, intercropping contributes significantly to food security and environmental stewardship. It represents a return to ecological wisdom, demonstrating that by working with nature, rather than against it, humanity can cultivate a more abundant and sustainable future. This ancient practice, revitalized by modern ecological understanding, holds immense promise for transforming agriculture into a truly regenerative force.