Nature’s Early Warning System: Understanding Indicator Species

Imagine a world where the health of an entire ecosystem could be understood by observing just a few key players. This is not a fantasy, but a fundamental principle in ecology, brought to life by what scientists call indicator species. These remarkable organisms act as nature’s sentinels, providing invaluable insights into the environmental conditions around them. They are the living barometers, the biological thermometers, signaling changes that might otherwise go unnoticed until it is too late.

From the smallest lichen clinging to a rock to the majestic salmon navigating a river, indicator species offer a window into the intricate web of life and the delicate balance that sustains it. Understanding their roles is crucial for conservation, environmental monitoring, and ultimately, for safeguarding the planet’s biodiversity and our own well-being.

The Original Alarm Bell: Canaries in the Coal Mine

The concept of an indicator species is perhaps best illustrated by a historical practice that saved countless lives. For centuries, coal miners faced the silent, invisible threat of toxic gases like carbon monoxide and methane. These gases could accumulate without warning, leading to tragic consequences.

Miners discovered that small, sensitive birds, particularly canaries, would react to these gases long before humans did. A canary’s distress, or even its collapse, served as a critical early warning, giving miners precious time to evacuate. This practice, though seemingly simple, highlights the core principle of indicator species: their heightened sensitivity makes them invaluable detectors of environmental hazards.

What Exactly Are Indicator Species?

At its heart, an indicator species is any species whose presence, absence, abundance, or health reflects a specific environmental condition or a characteristic of an ecosystem. They are biological surrogates, providing a snapshot of the overall health of an environment or signaling the presence of particular pollutants or stressors.

These species are often chosen because they have a narrow range of tolerance for certain environmental factors. This means they thrive only under specific conditions and decline rapidly when those conditions change. Their sensitivity makes them excellent early warning systems, much like the canaries in the coal mine, but on a much broader ecological scale.

How Do Nature’s Barometers Work?

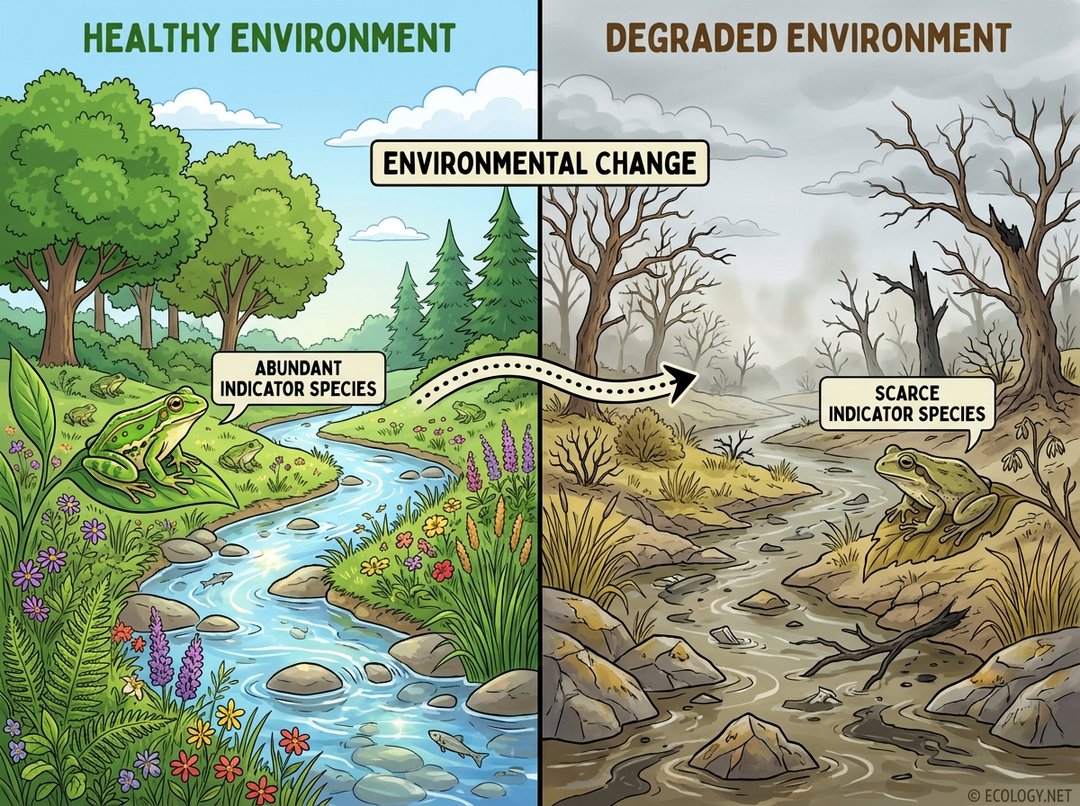

The mechanism by which indicator species function is elegantly simple yet profoundly effective. When an environment is healthy and stable, the indicator species associated with it will typically be present and thriving. Their populations will be robust, and individuals will exhibit good health.

However, when environmental conditions begin to degrade, perhaps due to pollution, habitat destruction, or climate change, the indicator species will be among the first to show signs of stress. This could manifest as:

- Absence: The species disappears entirely from an area where it once thrived.

- Decline in Population: Numbers of individuals decrease significantly.

- Poor Health: Individuals show signs of disease, deformities, or reduced reproductive success.

- Behavioral Changes: Altered feeding patterns, migration routes, or social interactions.

By monitoring these changes in indicator species, ecologists can infer the health of the broader ecosystem without needing to test every single environmental parameter directly. It is a cost-effective and holistic approach to environmental assessment.

Why Are Indicator Species So Important for Our Planet?

The value of indicator species extends far beyond their scientific intrigue. They play a critical role in:

- Early Warning Systems: They alert us to environmental problems before they become catastrophic, allowing for timely intervention.

- Cost-Effective Monitoring: Monitoring a few key species can be more efficient and economical than extensive chemical or physical testing across vast areas.

- Holistic Assessment: They provide a comprehensive view of ecosystem health, integrating multiple environmental factors that might be difficult to measure individually.

- Conservation Planning: Their status can guide conservation efforts, helping prioritize areas for protection or restoration.

- Public Engagement: Often charismatic, they can help communicate complex environmental issues to the public.

Diverse Examples from the Natural World

The natural world is teeming with examples of indicator species, each specialized to reflect particular environmental conditions. Here are a few prominent ones:

Lichens: Sentinels of Air Quality

These fascinating composite organisms, formed by a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and an alga or cyanobacterium, are incredibly sensitive to air pollution, particularly sulfur dioxide. Different species of lichens have varying tolerances:

- Crustose lichens can tolerate some pollution.

- Foliose lichens are more sensitive.

- Fruticose lichens, with their bushy forms, are highly sensitive and thrive only in very clean air.

Their presence or absence, and the diversity of species, can therefore indicate the level of air pollution in an area.

Aquatic Invertebrates: Barometers of Water Health

The tiny creatures living in streams and rivers, known as benthic macroinvertebrates, are excellent indicators of water quality. Species like mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies require clean, oxygen-rich water to survive. Their presence in abundance signals a healthy aquatic ecosystem. Conversely, the dominance of pollution-tolerant species like bloodworms or leeches, or the absence of sensitive species, indicates degraded water quality, often due to organic pollution or low oxygen levels.

Amphibians: Global Indicators of Ecosystem Health

Frogs, toads, and salamanders are often considered “canaries in the coal mine” for entire ecosystems. Their permeable skin makes them highly susceptible to pollutants in both water and air. They also occupy critical positions in food webs, making them sensitive to changes in prey availability or habitat quality. Declines in amphibian populations worldwide are a stark warning sign of widespread environmental degradation, including habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change.

Trout and Salmon: Indicators of Pristine Waters

Certain fish species, particularly trout and salmon, are highly demanding of their aquatic environments. They require cold, clean, well-oxygenated water, clear gravel beds for spawning, and unobstructed migratory routes. The health and abundance of these fish populations are strong indicators of the overall ecological integrity of river systems.

Butterflies: Reflectors of Habitat Quality and Climate Change

Butterflies are sensitive to changes in vegetation, temperature, and habitat fragmentation. Many species have specific host plants for their larvae, making them vulnerable to habitat alteration. Their relatively short lifespans and rapid reproductive cycles mean they can respond quickly to environmental shifts, making them useful indicators of habitat quality and even the impacts of climate change.

Characteristics of an Effective Indicator Species

Not every species makes a good indicator. Scientists look for several key characteristics when selecting an indicator species:

- High Sensitivity: It must respond predictably and significantly to the environmental change of interest.

- Widespread Distribution: It should be found over a broad geographical area to allow for comparisons.

- Easy to Monitor: It should be relatively easy to identify, count, and study without causing undue disturbance.

- Well-Understood Biology: Its life cycle, habitat requirements, and ecological role should be well-known.

- Specialized Niche: Species with very specific habitat or dietary requirements often make better indicators because they are more vulnerable to changes in those specific conditions.

Challenges and Limitations of Indicator Species

While incredibly valuable, indicator species are not a perfect solution and come with their own set of challenges:

- Specificity: A species might indicate a problem, but not always the exact cause. For example, a decline in frogs could be due to water pollution, habitat loss, or disease.

- Lag Time: Some species may show a delayed response to environmental changes, meaning significant damage might occur before the indicator signals a problem.

- Multiple Stressors: Ecosystems often face multiple environmental pressures simultaneously, making it difficult to attribute a species’ decline to a single cause.

- Species-Specific Responses: What indicates a problem for one species might not for another, or in a different region.

- Baseline Data: Effective monitoring requires good baseline data on the species’ natural population fluctuations and health in undisturbed conditions.

Therefore, indicator species are best used as part of a broader monitoring strategy, often alongside direct environmental measurements.

Beyond the Basics: Applications in Conservation and Management

The application of indicator species extends into various fields of environmental science and management:

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs): Before major development projects, indicator species are often studied to predict and monitor potential ecological impacts.

- Restoration Project Monitoring: The return or recovery of specific indicator species can signal the success of habitat restoration efforts.

- Climate Change Tracking: Shifts in the distribution or phenology (timing of biological events) of certain species can indicate the effects of global warming.

- Biodiversity Assessments: Indicator species can sometimes serve as surrogates for overall biodiversity, especially in groups that are difficult to survey comprehensively.

- Pollution Bio-monitoring: Specific species are used to detect and quantify the presence of particular pollutants, such as heavy metals or persistent organic pollutants.

Conclusion: Listening to Nature’s Voices

Indicator species are truly remarkable organisms, offering humanity a profound way to listen to the subtle whispers and urgent cries of the natural world. They remind us that every living thing is interconnected and that the health of one species can reflect the health of an entire ecosystem. By understanding and carefully monitoring these biological sentinels, we gain invaluable tools for protecting our environment, making informed conservation decisions, and ensuring a healthier future for all life on Earth. Their stories are a testament to nature’s intricate design and a powerful call to action for environmental stewardship.